Ribavirin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌraɪbəˈvaɪrɪn/ RY-bə-VY-rin |

| Trade names | Copegus, Rebetol, Virazole, other[1] |

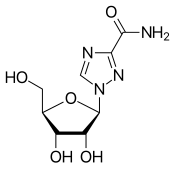

| Other names | 1-(β-D-Ribofuranosyl)-1"H"-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide, tribavirin (BAN UK) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605018 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, Inhalation |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 64%[5] |

| Protein binding | 0%[5] |

| Metabolism | liver and intracellularly[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 298 hours (multiple dose); 43.6 hours (single dose)[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (61%), faeces (12%)[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.587 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H12N4O5 |

| Molar mass | 244.207 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 166 to 168 °C (331 to 334 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ribavirin, also known as tribavirin, is an antiviral medication used to treat illness caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, as well as some viral hemorrhagic fevers.[1] For HCV, it is used in combination with other medications, such as simeprevir, sofosbuvir, peginterferon alfa-2b or peginterferon alfa-2a.[1] It can also be used for viral hemorrhagic fevers—specifically, for Lassa fever, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, and Hantavirus infections (with exceptions for Ebola or Marburg virus diseases).[1] Ribavirin is usually taken orally (by mouth) or inhaled.[1] Despite widespread usage, it has faced scrutiny in the 21st century because of lack of proven efficacy in treating viral infections for which it has been prescribed in the past.[6][7]

Its common side effects include fatigue, headache, nausea, fever, muscle pains, and an irritable mood.[1] Serious side effects include red blood cell breakdown, liver problems, and allergic reactions.[1] Its use during pregnancy can bring harm to the developing fetus.[1] Effective birth control is recommended for both males and females for at least seven months during and after use.[8] The mechanism of action of ribavirin is not entirely clear.[1]

Ribavirin was patented in 1971 and approved for medical use in 1986.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10] It is available as a generic medication.[1]

Medical uses

[edit]Ribavirin is primarily used to treat chronic hepatitis C and viral hemorrhagic fevers (an orphan indication in most countries).[11] Its efficacy for these purposes has been questioned in light of its Food and Drug Administration boxed warning against its use as monotherapy for chronic hepatitis C. Thus, it may be prescribed in the United States only as an adjunct to one or more other medications. Its efficacy against viruses other than HCV, including those that cause viral hemorrhagic fever, has not been conclusively demonstrated. In effect, it is not approved in the United States for treatment of viruses other than HCV.[7][6]

Hepatitis C

[edit]For chronic HCV infection, the oral (capsule or tablet) form of ribavirin is used only in combination with pegylated interferon alfa.[6][12][13][14][15] Statins may improve this combination's efficacy in treating hepatitis C.[16] When possible, genotyping of the specific viral strain is done; and ribavirin is only used as a dose-escalating[a] adjuvant to specific combinations of genotypes and other medications.[17]

Acute hepatitis C infection (within the first 6 months) often does not require immediate treatment, as many infections eventually resolve without treatment.[18] When the decision is made to treat acute hepatitis C, ribavirin may be used as an adjunct to several drug combinations.[17] However, other medications are still preferred.[17][18]

Viral hemorrhagic fever

[edit]Ribavirin is the only known treatment for a variety of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Lassa fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever, and Hantavirus infection, although data regarding these infections are scarce and the drug might be effective only in early stages.[19][20][21][22] It is noted by the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) that "Ribavirin has poor in vitro and in vivo activity against the filoviruses (Ebola[23] and Marburg) and the flaviviruses (dengue, yellow fever, Omsk hemorrhagic fever, and Kyasanur forest disease)"[24] The aerosol form has been used in the past to treat respiratory syncytial virus-related diseases in children, although the evidence to support this is rather weak.[25]

Despite questions surrounding its efficacy, ribavirin remains the only antiviral known to be effective in treating Lassa fever.[26]

It has been used (in combination with ketamine, midazolam, and amantadine) in treatment of rabies.[27]

Experimental uses

[edit]Experimental data indicate that ribavirin may have useful activity against canine distemper and poxviruses.[28][29] Ribavirin has also been used as a treatment for herpes simplex virus. One small study found that ribavirin treatment reduced the severity of herpes outbreaks and promoted recovery, as compared with placebo treatment.[30] Another study found that ribavirin potentiated the antiviral effect of acyclovir.[31]

Some interest has been seen in its possible use as a treatment for cancers with elevated eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E, especially acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as well as in head and neck cancers.[32][33][34][35] Ribavirin targeted eIF4E in AML patients in monotherapy and combination studies and this corresponded to objective clinical responses including complete remissions.[36][37][38] Ribavirin resistance in AML patients arose leading to loss of eIF4E targeting and relapse. Resistance was caused by deactivation of ribavirin through its glucuronidation in AML cells or impaired drug entry/retention in the AML cells.[39] There may be additional forms of ribavirin resistance displayed by cancer cells. In HPV related oropharyngeal cancers, ribavirin reduced levels of phosphorylated form of eIF4E in some patients.[35] The best response here was stable disease but another head and neck study had more promising results.[34]

Adverse effects

[edit]The medication has two FDA "black box" warnings: One raises concerns that use before or during pregnancy by either sex may result in birth defects in the baby, and the other is regarding the risk of red blood cell breakdown.[40]

Ribavirin should not be given with zidovudine because of the increased risk of anemia;[41] concurrent use with didanosine should likewise be avoided because of an increased risk of mitochondrial toxicity.[42]

Mechanisms of action

[edit]It is a guanosine (ribonucleic) analog used to stop viral RNA synthesis and viral mRNA capping, thus, it is a nucleoside analog. Ribavirin is a prodrug, which when metabolized resembles purine RNA nucleotides. In this form, it interferes with RNA metabolism required for viral replication. Over five direct and indirect mechanisms have been proposed for its mechanism of action.[43] The enzyme inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPase) dephosphorylates ribavirin triphosphate in vitro to ribavirin monophosphate, and ITPase reduced enzymatic activity present in 30% of humans potentiates mutagenesis in hepatitis C virus.[44]

RNA viruses

[edit]Ribavirin's amide group can make the native nucleoside drug resemble adenosine or guanosine, depending on its rotation. For this reason, when ribavirin is incorporated into RNA, as a base analog of either adenine or guanine, it pairs equally well with either uracil or cytosine, inducing mutations in RNA-dependent replication in RNA viruses. Such hypermutation can be lethal to RNA viruses.[45][46]

DNA viruses

[edit]Neither of these mechanisms explains ribavirin's effect on many DNA viruses, which is more of a mystery, especially given the complete inactivity of ribavirin's 2' deoxyribose analogue, which suggests that the drug functions only as an RNA nucleoside mimic, and never a DNA nucleoside mimic. Ribavirin 5'-monophosphate inhibits cellular inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, thereby depleting intracellular pools of GTP.[47][failed verification]

eIF4E targeting in cancer

[edit]This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources, specifically: eIF4E targeting in cancer. (April 2023) |  |

The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E plays multiple roles in RNA metabolism with translation being the best described. Biophysical and NMR studies first revealed that ribavirin directly bound the eIF4E, providing another mechanism for its action.[48][49][50][39] 3H Ribavirin also interacts with eIF4E in cells.[39][33] While inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) presumably only binds the ribavirin monophosphate metabolite (RMP), eIF4E can bind ribavirin and with higher affinity ribavirin's phosphorylated forms.[48][49][33] In many cell lines, studies into steady state levels of metabolites indicate that ribavirin triphosphate (RTP) is more abundant than the RMP metabolite which is the IMPDH ligand.[51][52] RTP binds to eIF4E in its cap-binding site as observed by NMR.[50] Ribavirin inhibits eIF4E activities in cells including in its RNA export, translation and oncogenic activities lines.[48][49][53][54][39][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62] In AML patients treated with ribavirin, ribavirin blocked the nuclear import of eIF4E through interfering with its interaction with its nuclear importer, Importin 8, thereby impairing its nuclear activities.[63][38][37][39] Clinical relapse in AML patients corresponded to loss of ribavirin binding leading to nuclear re-entry of eIF4E and re-emergence of its nuclear activities.[63][38][37][39]

History and culture

[edit]Ribavirin was first made in 1972 under the National Cancer Institute's Virus-Cancer program.[64] This was done by researchers from International Chemical and Nuclear Corporation including Roberts A. Smith, Joseph T. Witkovski and Roland K. Robins.[65] It was reported that ribavirin was active against a variety of RNA and DNA viruses in culture and in animals, without undue toxicity in the context of cancer chemotherapies.[66] By the late 1970s, the Virus-Cancer program was widely considered a failure, and the drug development was abandoned.[citation needed]

After the US Government announced that AIDS was caused by a retrovirus in 1984, drugs examined during the Virus-Cancer program and its focus on retroviruses were re-examined. Although the FDA first approved ribavirin as an antiviral in 1986, it was not indicated to treat HIV or AIDS. As a result, many people with AIDS sought to obtain black market ribavirin via buyer's clubs. The drug was approved for investigational use against hantavirus in the United States in 1993, but the results from a non-randomized uncontrolled trial were not encouraging: 71% of recipients became anemic and 47% died.

In 2002 with the SARS outbreak, early speculation focused on ribavirin as a possible anti-SARS agent.[67] Early protocols adopted in Hong Kong adopted a "Hit Hard Hit Early" approach treating SARS with high doses of off-label steroids and Ribavirin.[68] Unfortunately, it later turned out this haphazard approach was at best ineffective and at worst fatal, with many deaths attributed to SARS caused by ribavirin toxicity.[69][unreliable source?]

Names

[edit]Ribavirin is the INN and USAN, whereas tribavirin is the BAN. Brand names of generic forms include Copegus, Ribasphere, Rebetol.[1]

Derivatives

[edit]Ribavirin is possibly best viewed as a ribosyl purine analogue with an incomplete purine 6-membered ring. This structural resemblance historically prompted replacement of the 2' nitrogen of the triazole with a carbon (which becomes the 5' carbon in an imidazole), in an attempt to partly "fill out" the second ring--- but to no great effect. Such 5' imidazole riboside derivatives show antiviral activity with 5' hydrogen or halide, but the larger the substituent, the smaller the activity, and all proved less active than ribavirin.[70] Note that two natural products were already known with this imidazole riboside structure: substitution at the 5' carbon with OH results in pyrazofurin, an antibiotic with antiviral properties but unacceptable toxicity, and replacement with an amino group results in the natural purine synthetic precursor 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR), which has only modest antiviral properties.[citation needed]

Taribavirin

[edit]The most successful ribavirin derivative to date is the 3-carboxamidine derivative of the parent 3-carboxamide, first reported in 1973 by J. T. Witkowski et al.,[71] and now called taribavirin (former names "viramidine" and "ribamidine"). This drug shows a similar spectrum of antiviral activity to ribavirin, which is not surprising as it is now known to be a pro-drug for ribavirin. Taribavirin, however, has useful properties of less erythrocyte-trapping and better liver-targeting than ribavirin. The first property is due to taribavirin's basic amidine group which inhibits drug entry into RBCs, and the second property is probably due to increased concentration of the enzymes which convert amidine to amide in liver tissue.[72] Taribavirin completed phase III human trials in 2012.[73]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Begins with a low dose, at or near the lowest point of the expected therapeutic index, and then the dose is progressively increased until achieving desired effects.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Ribavirin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "Ribavirin (Ibavyr)". Catie. 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "PRODUCT INFORMATION REBETOL (RIBAVIRIN) CAPSULES" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Safrin S (2024). "Chapter 49: Antiviral Agents". Katzung's Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill. Other antiviral agents: Ribavirin.

- ^ a b "Copegus: Package Insert". Drugs.com. 2023-03-27. Retrieved 2024-01-19.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 177. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 504. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Rebetol, Ribasphere (ribavirin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Paeshuyse J, Dallmeier K, Neyts J (December 2011). "Ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the proposed mechanisms of action". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (6): 590–598. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.030. PMID 22440916.

- ^ Flori N, Funakoshi N, Duny Y, Valats JC, Bismuth M, Christophorou D, et al. (March 2013). "Pegylated interferon-α2a and ribavirin versus pegylated interferon-α2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C : a meta-analysis". Drugs. 73 (3): 263–277. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0027-1. PMID 23436591. S2CID 46334977.

- ^ Druyts E, Thorlund K, Wu P, Kanters S, Yaya S, Cooper CL, et al. (April 2013). "Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 56 (7): 961–967. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1031. PMID 23243171.

- ^ Zeuzem S, Poordad F (July 2010). "Pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin therapy in the treatment of CHC: individualization of treatment duration according to on-treatment virologic response". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 26 (7): 1733–1743. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.487038. PMID 20482242. S2CID 206965239.

- ^ Zhu Q, Li N, Han Q, Zhang P, Yang C, Zeng X, et al. (June 2013). "Statin therapy improves response to interferon alfa and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Antiviral Research. 98 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.04.009. PMID 23603497.

- ^ a b c Chung RT, Ghany MG, Kim AY, Marks KM, Naggie S, Vargas HE, et al. (AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel) (October 2018). "Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 67 (10): 1477–1492. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy585. PMC 7190892. PMID 30215672.

- ^ a b Pawlotsky J, Negro F, Aghemo A, Berenguer M, Dalgard O, Dusheiko G, et al. (August 2018). "EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018". Journal of Hepatology. 69 (2): 461–511. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026. PMID 29650333.

- ^ Steckbriefe seltener und importierter Infektionskrankheiten [Characteristics of rare and imported infectious diseases] (PDF). Berlin: Robert Koch Institute. 2006. ISBN 978-3-89606-095-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-29.

- ^ Ascioglu S, Leblebicioglu H, Vahaboglu H, Chan KA (June 2011). "Ribavirin for patients with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 66 (6): 1215–1222. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr136. PMID 21482564.

- ^ Bausch DG, Hadi CM, Khan SH, Lertora JJ (December 2010). "Review of the literature and proposed guidelines for the use of oral ribavirin as postexposure prophylaxis for Lassa fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 51 (12): 1435–1441. doi:10.1086/657315. PMC 7107935. PMID 21058912.

- ^ Soares-Weiser K, Thomas S, Thomson G, Garner P (July 2010). "Ribavirin for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Infectious Diseases. 10: 207. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-207. PMC 2912908. PMID 20626907.

- ^ Goeijenbier M, van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Koopmans MP, van Gorp EC (November 2014). "Ebola virus disease: a review on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 72 (9): 442–448. PMID 25387613. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook. United States Government Printing Office. 2011. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-16-090015-0.

- ^ Ventre K, Randolph AG (January 2007). Ventre K (ed.). "Ribavirin for respiratory syncytial virus infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000181.pub3. PMID 17253446.

- ^ "Treatment | Lassa Fever | CDC". 2023-09-26. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ Hemachudha T, Ugolini G, Wacharapluesadee S, Sungkarat W, Shuangshoti S, Laothamatas J (May 2013). "Human rabies: neuropathogenesis, diagnosis, and management". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (5): 498–513. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70038-3. PMID 23602163. S2CID 1798889.

- ^ Elia G, Belloli C, Cirone F, Lucente MS, Caruso M, Martella V, et al. (February 2008). "In vitro efficacy of ribavirin against canine distemper virus". Antiviral Research. 77 (2): 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.004. PMID 17949825.

- ^ Baker RO, Bray M, Huggins JW (January 2003). "Potential antiviral therapeutics for smallpox, monkeypox and other orthopoxvirus infections". Antiviral Research. 57 (1–2): 13–23. doi:10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00196-1. PMC 9533837. PMID 12615299.

- ^ Bierman SM, Kirkpatrick W, Fernandez H (1981). "Clinical efficacy of ribavirin in the treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection". Chemotherapy. 27 (2): 139–145. doi:10.1159/000237969. PMID 7009087.

- ^ Pancheva SN (September 1991). "Potentiating effect of ribavirin on the anti-herpes activity of acyclovir". Antiviral Research. 16 (2): 151–161. doi:10.1016/0166-3542(91)90021-I. PMID 1665959.

- ^ Kast RE (November–December 2002). "Ribavirin in cancer immunotherapies: controlling nitric oxide helps generate cytotoxic lymphocyte". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 1 (6): 626–630. doi:10.4161/cbt.310. PMID 12642684. S2CID 24010404.

- ^ a b c Borden KL, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B (October 2010). "Ribavirin as an anti-cancer therapy: acute myeloid leukemia and beyond?". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 51 (10): 1805–1815. doi:10.3109/10428194.2010.496506. PMC 2950216. PMID 20629523.

- ^ a b Dunn LA, Fury MG, Sherman EJ, Ho AA, Katabi N, Haque SS, et al. (February 2018). "Phase I study of induction chemotherapy with afatinib, ribavirin, and weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel for stage IVA/IVB human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer". Head & Neck. 40 (2): 233–241. doi:10.1002/hed.24938. PMC 6760238. PMID 28963790.

- ^ a b Burman B, Drutman SB, Fury MG, Wong RJ, Katabi N, Ho AL, et al. (May 2022). "Pharmacodynamic and therapeutic pilot studies of single-agent ribavirin in patients with human papillomavirus-related malignancies". Oral Oncology. 128: 105806. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.105806. PMC 9788648. PMID 35339025.

- ^ Assouline S, Culjkovic B, Cocolakis E, Rousseau C, Beslu N, Amri A, et al. (July 2009). "Molecular targeting of the oncogene eIF4E in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a proof-of-principle clinical trial with ribavirin". Blood. 114 (2): 257–260. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-02-205153. PMID 19433856. S2CID 28957125.

- ^ a b c Assouline S, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Bergeron J, Caplan S, Cocolakis E, Lambert C, et al. (January 2015). "A phase I trial of ribavirin and low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia with elevated eIF4E". Haematologica. 100 (1): e7–e9. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.111245. PMC 4281321. PMID 25425688.

- ^ a b c Assouline S, Gasiorek J, Bergeron J, Lambert C, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Cocolakis E, et al. (March 2023). "Molecular targeting of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes in high-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E refractory/relapsed acute myeloid leukemia patients: a randomized phase II trial of vismodegib, ribavirin with or without decitabine". Haematologica. 108 (11): 2946–2958. doi:10.3324/haematol.2023.282791. PMC 10620574. PMID 36951168. S2CID 257733013.

- ^ a b c d e f Zahreddine HA, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Assouline S, Gendron P, Romeo AA, Morris SJ, et al. (July 2014). "The sonic hedgehog factor GLI1 imparts drug resistance through inducible glucuronidation". Nature. 511 (7507): 90–93. Bibcode:2014Natur.511...90Z. doi:10.1038/nature13283. PMC 4138053. PMID 24870236.

- ^ "Copedgus" (PDF). FDA.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Alvarez D, Dieterich DT, Brau N, Moorehead L, Ball L, Sulkowski MS (October 2006). "Zidovudine use but not weight-based ribavirin dosing impacts anaemia during HCV treatment in HIV-infected persons". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 13 (10): 683–689. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00749.x. PMID 16970600. S2CID 21474337.

- ^ Bani-Sadr F, Carrat F, Pol S, Hor R, Rosenthal E, Goujard C, et al. (Anrs Hc02-Ribavic Study Team) (September 2005). "Risk factors for symptomatic mitochondrial toxicity in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients during interferon plus ribavirin-based therapy". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 40 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000174649.51084.46. PMID 16123681. S2CID 9364536.

- ^ Graci JD, Cameron CE (January 2006). "Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses". Reviews in Medical Virology. 16 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1002/rmv.483. PMC 7169142. PMID 16287208.

- ^ Nyström K, Wanrooij PH, Waldenström J, Adamek L, Brunet S, Said J, et al. (October 2018). "Inosine Triphosphate Pyrophosphatase Dephosphorylates Ribavirin Triphosphate and Reduced Enzymatic Activity Potentiates Mutagenesis in Hepatitis C Virus". Journal of Virology. 92 (19): 01087–18. doi:10.1128/JVI.01087-18. PMC 6146798. PMID 30045981.

- ^ Ortega-Prieto AM, Sheldon J, Grande-Pérez A, Tejero H, Gregori J, Quer J, et al. (2013). Vartanian JP (ed.). "Extinction of hepatitis C virus by ribavirin in hepatoma cells involves lethal mutagenesis". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e71039. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...871039O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071039. PMC 3745404. PMID 23976977.

- ^ Crotty S, Cameron C, Andino R (February 2002). "Ribavirin's antiviral mechanism of action: lethal mutagenesis?". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 80 (2): 86–95. doi:10.1007/s00109-001-0308-0. PMID 11907645. S2CID 52851826.

- ^ Leyssen P, De Clercq E, Neyts J (April 2006). "The anti-yellow fever virus activity of ribavirin is independent of error-prone replication". Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (4): 1461–1467. doi:10.1124/mol.105.020057. PMID 16421290. S2CID 8158590.

- ^ a b c Kentsis A, Topisirovic I, Culjkovic B, Shao L, Borden KL (December 2004). "Ribavirin suppresses eIF4E-mediated oncogenic transformation by physical mimicry of the 7-methyl guanosine mRNA cap". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (52): 18105–18110. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10118105K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406927102. PMC 539790. PMID 15601771.

- ^ a b c Kentsis A, Volpon L, Topisirovic I, Soll CE, Culjkovic B, Shao L, et al. (December 2005). "Further evidence that ribavirin interacts with eIF4E". RNA. 11 (12): 1762–1766. doi:10.1261/rna.2238705. PMC 1370864. PMID 16251386.

- ^ a b Volpon L, Osborne MJ, Zahreddine H, Romeo AA, Borden KL (May 2013). "Conformational changes induced in the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E by a clinically relevant inhibitor, ribavirin triphosphate". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 434 (3): 614–619. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.125. PMC 3659399. PMID 23583375.

- ^ Smee DF, Matthews TR (July 1986). "Metabolism of ribavirin in respiratory syncytial virus-infected and uninfected cells". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 30 (1): 117–121. doi:10.1128/AAC.30.1.117. PMC 176447. PMID 3752974.

- ^ Page T, Connor JD (January 1990). "The metabolism of ribavirin in erythrocytes and nucleated cells". The International Journal of Biochemistry. 22 (4): 379–383. doi:10.1016/0020-711X(90)90140-X. PMID 2159925.

- ^ Pettersson F, Yau C, Dobocan MC, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Retrouvey H, Puckett R, et al. (May 2011). "Ribavirin treatment effects on breast cancers overexpressing eIF4E, a biomarker with prognostic specificity for luminal B-type breast cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (9): 2874–2884. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2334. PMC 3086959. PMID 21415224.

- ^ Bollmann F, Fechir K, Nowag S, Koch K, Art J, Kleinert H, et al. (April 2013). "Human inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression depends on chromosome region maintenance 1 (CRM1)- and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (elF4E)-mediated nucleocytoplasmic mRNA transport". Nitric Oxide. 30: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2013.02.083. PMID 23471078.

- ^ Shi F, Len Y, Gong Y, Shi R, Yang X, Naren D, et al. (2015-08-28). Eaves CJ (ed.). "Ribavirin Inhibits the Activity of mTOR/eIF4E, ERK/Mnk1/eIF4E Signaling Pathway and Synergizes with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Imatinib to Impair Bcr-Abl Mediated Proliferation and Apoptosis in Ph+ Leukemia". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0136746. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036746S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136746. PMC 4552648. PMID 26317515.

- ^ Zismanov V, Attar-Schneider O, Lishner M, Heffez Aizenfeld R, Tartakover Matalon S, Drucker L (February 2015). "Multiple myeloma proteostasis can be targeted via translation initiation factor eIF4E". International Journal of Oncology. 46 (2): 860–870. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2774. PMID 25422161.

- ^ Dai D, Chen H, Tang J, Tang Y (January 2017). "Inhibition of mTOR/eIF4E by anti-viral drug ribavirin effectively enhances the effects of paclitaxel in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 482 (4): 1259–1264. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.025. PMID 27932243.

- ^ Volpin F, Casaos J, Sesen J, Mangraviti A, Choi J, Gorelick N, et al. (May 2017). "Use of an anti-viral drug, Ribavirin, as an anti-glioblastoma therapeutic". Oncogene. 36 (21): 3037–3047. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.457. PMID 27941882. S2CID 21655102.

- ^ Wang G, Li Z, Li Z, Huang Y, Mao X, Xu C, et al. (December 2017). "Targeting eIF4E inhibits growth, survival and angiogenesis in retinoblastoma and enhances efficacy of chemotherapy". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 96: 750–756. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.034. PMID 29049978.

- ^ Xi C, Wang L, Yu J, Ye H, Cao L, Gong Z (September 2018). "Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E is effective against chemo-resistance in colon and cervical cancer". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 503 (4): 2286–2292. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.150. PMID 29959920. S2CID 49634908.

- ^ Jin J, Xiang W, Wu S, Wang M, Xiao M, Deng A (March 2019). "Targeting eIF4E signaling with ribavirin as a sensitizing strategy for ovarian cancer". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 510 (4): 580–586. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.117. PMID 30739792. S2CID 73419809.

- ^ Urtishak KA, Wang LS, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Davenport JW, Porazzi P, Vincent TL, et al. (March 2019). "Targeting EIF4E signaling with ribavirin in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Oncogene. 38 (13): 2241–2262. doi:10.1038/s41388-018-0567-7. PMC 6440839. PMID 30478448.

- ^ a b Volpon L, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Osborne MJ, Ramteke A, Sun Q, Niesman A, et al. (May 2016). "Importin 8 mediates m7G cap-sensitive nuclear import of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (19): 5263–5268. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.5263V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1524291113. PMC 4868427. PMID 27114554.

- ^ Snell NJ (August 2001). "Ribavirin--current status of a broad spectrum antiviral agent". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2 (8): 1317–1324. doi:10.1517/14656566.2.8.1317. PMID 11585000. S2CID 46564870.

- ^ "Ribavirin History". News-Medical.net. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2016-03-02. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ Sidwell RW, Huffman JH, Khare GP, Allen LB, Witkowski JT, Robins RK (August 1972). "Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of Virazole: 1-beta-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide". Science. 177 (4050): 705–706. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..705S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4050.705. PMID 4340949. S2CID 43106875.

- ^ Koren G, King S, Knowles S, Phillips E (May 2003). "Ribavirin in the treatment of SARS: A new trick for an old drug?". CMAJ. 168 (10): 1289–1292. PMC 154189. PMID 12743076.

- ^ Leung CW, Kwan YW, Ko PW, Chiu SS, Loung PY, Fong NC, et al. (June 2004). "Severe acute respiratory syndrome among children". Pediatrics. 113 (6): e535–e543. doi:10.1542/peds.113.6.e535. PMID 15173534.

- ^ Crowe D (February 2020). "SARS - Sterioid and Ribavirin Scandal". Unpublished Preprint. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.25308.74881 – via researchgate.net.

Author died before publication

- ^ Smith RA, Kirkpatrick W, eds. (1980). "Ribavirin: structure and antiviral activity relationships". Ribavirin: A Broad Spectrum Antiviral Agent. New York: Academic Press. pp. 1–21.

- ^ Witkowski JT, Robins RK, Khare GP, Sidwell RW (August 1973). "Synthesis and antiviral activity of 1,2,4-triazole-3-thiocarboxamide and 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamidine ribonucleosides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (8): 935–937. doi:10.1021/jm00266a014. PMID 4355593.

- ^ Sidwell RW, Bailey KW, Wong MH, Barnard DL, Smee DF (October 2005). "In vitro and in vivo influenza virus-inhibitory effects of viramidine". Antiviral Research. 68 (1): 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.003. PMID 16087250.

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine (2012-06-22). Study of Viramidine to Ribavirin in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Who Are Treatment Naive (VISER2) (Report). National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

External links

[edit]- "Ribavirin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.