Tres (instrument)

Cuban tres | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tres, tres cubano |

| Classification | String instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.322 (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed | 19th century in eastern Cuba |

| Related instruments | |

| Bandola, bandurria, laúd, Spanish guitar, tiple, cuatro | |

The tres (Spanish for three) is a three-course chordophone of Cuban origin. The most widespread variety of the instrument is the original Cuban tres with six strings. Its sound has become a defining characteristic of the Cuban son and it is commonly played in a variety of Afro-Cuban genres. In the 1930s, the instrument was adapted into the Puerto Rican tres, which has nine strings and a body similar to that of the cuatro.

The tres developed in the second half of the 19th century in the eastern region of Guantánamo, where it was used to play changüí, a precursor of son cubano.[1] Its exact origins are not known, but it is assumed to have developed from the 19th century Spanish guitar, which it resembles in shape,[2] as well as the laúd and bandola, two instruments used in punto cubano since at least the 18th century.[2] Tres playing revolves around the guajeo, an ostinato pattern found in many Afro-Cuban music styles. Tres players are commonly known as treseros (in Cuba) or tresistas (in Puerto Rico).

Cuba

[edit]History

[edit]

By most accounts, the tres was first used in several related Afro-Cuban musical genres originating in eastern Cuba: the nengón, kiribá, changüí and son, all of which developed during the 19th century. Benjamin Lapidus states: "The tres holds a position of great importance not only in changüí, but in the musical culture of Cuba as a whole."[3] One theory holds that initially, a guitar, tiple or bandola, was used in the son. They were eventually replaced by a new native-born instrument, a fusion of all three, called the tres. Helio Orovio writes that, in 1892, Nené Manfugás brought the tres from Baracoa, its place of origin, to Santiago de Cuba.[4] According to Sindo Garay, the tres itself originated in Baracoa.[1] In 1927, Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes mentioned Nené Manfugás as the first tres player from Santiago de Cuba.[5] However, he described the tres as having originated in "time immemorial" among Afro-Cubans, while bearing a strong resemblance to the Spanish guitar and the bandurria.[5][6] According to writer Alejo Carpentier, the tres descended from the bandola (itself a derivative of the Spanish bandurria), which lost two courses over time.[7][6] According to journalist Lino Dou, the tres was virtually unknown in western Cuba until 1895, when it was bought from Oriente by the mambises.[6] Similarly, Fernando Ortiz stated that the wars between Spain and Cuba (Ten Years' War and Cuban War of Independence) gave rise to the differentiation between the Spanish guitar and the Cuban tres, the latter becoming a symbol of the creole nation.[6] Ortiz asserted that the tres most likely originated during pre-colonial Cuba, before gaining widespread popularity in the late 19th century.[6] The origins of the tres and other Cuban instruments are discussed in depth by Ortiz in his seminal work Los instrumentos de la música afrocubana, published between 1952 and 1955.

As the son cubano grew in popularity in the 1920s, so did the tres. By the 1930s, there were several rising stars of the tres, including Eliseo Silveira, Carlos Godínez, Arsenio Rodríguez and Niño Rivera.[8] In the 1950s, Arsenio left Cuba and his sound was continued by Ramón Cisneros "Liviano" and Arturo Harvey "Alambre Dulce" in the Conjunto Chappottín. Other important treseros of the 1950s such as Senén Suárez and Juanito Márquez began making recordings with electric treses. In the United States, the tres was sometimes featured in salsa ensembles, especially in the 1970s, when players such as Nelson González, Charlie Rodríguez and Harry Viggiano made numerous recordings for Fania Records. Traditional tres playing has been promoted in Cuba since the first recordings by Grupo Changüí de Guantánamo in the 1980s, featuring Chito Latamblé, as well as the albums by Isaac Oviedo and his son Papi Oviedo. In 2010, tresero Pancho Amat won the highest accolade awarded to musicians in Cuba, the Premio Nacional de Música.[9]

Description and variants

[edit]The Cuban tres is significantly smaller than the Spanish guitar, with a scale length between 48 centimetres (19 in) and 65 centimetres (26 in).[10] It has three courses (groups) of two strings each for a total of six strings. From the low pitch to the highest, the principal tuning is in one of two variants in C Major, either: G4 G3, C4 C4, E4 E4 (top course in unisons), or more traditionally: G4 G3, C4 C4, E3 E4 (top course in octaves). Note that when the octave tuning is used, the order of the octaves in the first course is the reverse of the order in the third course (low-high versus high-low).[11] Today many treseros tune the whole instrument a step higher (in D major): A4 A3, D4 D4, F#4 F#4 or A4 A3, D4 D4, F#3 F#4.

A musician who plays the Cuban tres is called a tresero, although the term tresista has also been used in Cuba in the past.[5] There are variants of the instrument in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.[12] Cuban trova singer, songwriter and guitarist Compay Segundo invented a variant of the tres and the Spanish guitar known as armónico.[13] Eliades Ochoa plays another variant he calls the guitarra tres, which is a Spanish guitar with two extra strings tuned like a tres.[14]

Guajeos

[edit]The typical tres ostinato is the guajeo. It emerged in Cuba in the 19th century in the musical genres nengón, kiribá, changüí, and son.[15] The tres playing technique of changüí, and to a lesser extent nengón, has influenced contemporary son musicians, most notably pianist Lilí Martínez and tresero Pancho Amat, both of whom learned the style from Chito Latamblé.[16][17] Both nengón and kiribá are included in the repertoire of changüí ensembles. For example, the debut album of Grupo Changüí de Guantánamo opens with "Nengón".[18]

Nengón

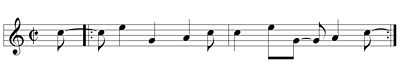

[edit]Benjamin Lapidus presents evidence of the "linear view of the son's development from nengón to kiribá and other regional styles, to changüí, and ultimately to son."[19] The nengón has a limited harmonic range, where the tonic and dominant are accentuated, and the tres is usually placed in the traditional octave tuning (G4 G3, C4 C4, E3 E4). As a genre, nengón consists of variations of a single song, "Para ti nengón". The following nengón guajeo is an embellishment of the rhythmic figure known as tresillo.

Kiribá

[edit]Closely related to nengón, the kiribá style emerged in the Baracoa region of eastern Cuba.[20] Like nengón, kiribá is genre that is based on the song or refrain "Kiribá, kiribá". Because of this, Cuban musicologists such as Olavo Alén Rodríguez prefer to categorise kiribá as a style within changüí.[21] Nonetheless, kiribá has a distinct guajeo and might predate changüí.

Changüí

[edit]When playing changüí, the tres is again usually given the traditional octave tuning. The following changüí tres guajeo consists of all offbeats.[22]

Son

[edit]According to Kevin Moore "there are two types of pure son tres guajeos: generic and song-specific. Song-specific guajeos are usually based on the song's melody, while the generic type involves simply arpeggiating triads."[23] The rhythmic pattern of the following "generic" guajeo is used in many songs. Note that the first measure consists of all offbeats. The figure can begin in the first measure, or the second measure, depending upon the structure of the song.

Solos

[edit]Tres solos were first constructed by grouping guajeo variations together, a melodic/rhythmic approach relying on subtle variation and repetition, that maintains a "groove" for dancers. According to Lapidus, tres solos in changüí typically sound "melodic/rhythmic ideas twice before moving on. This technique allows the soloist to set up a series of expectations for the listener, which are alternately satisfied, circumvented, frustrated, or inverted. The practice has its analogue in what Paul Berliner labels 'a community of ideas,' as motives from these sequences are frequently returned to throughout the course of any given solo."[24]

By the mid twentieth century, tres solos began incorporating the rhythmic "vocabulary" of quinto, the lead drum of rumba.[25] The counter-metric emphasis of quinto-based phrases break free from the confines of the guajeo, which is normally "locked" to the clave cycle. Thus, quinto-based solos are capable of creating long cycles of tension—release spanning many measures.

Puerto Rico

[edit]

The Puerto Rican tres is an adaptation of Cuban tres with nine strings instead of six. Although nine-string treses are documented in Cuba since at least 1913,[26] investigators agree that the creation of the instrument was probably caused by the 1929 visit of Isaac Oviedo to Puerto Rico during a tour by the Septeto Matancero. Inspired by Oviedo, guitarist Guillero "Piliche" Ayala ordered the construction of a similar instrument for which the body of a cuatro was used.[27] As a result, the Puerto Rican tres is shaped like a Puerto Rican cuatro, with cut-outs, unlike the Cuban variety, which has a guitar-like shape. By 1934, the Puerto Rican cuatro had reached New York and nowadays most Puerto Rican tres players specialize in their national adaptation of the instrument, a notable exception being Nelson González. The Puerto Rican tres has nine strings in three courses and is tuned G4 G3 G4, C4 C4 C4, E4 E3 E4. Players of the Puerto Rican tres are called tresistas.

Notable players

[edit]The following are some of the most influential performers of the Cuban tres.[28][29][30]

- Efraín Amador

- Pancho Amat

- Félix Cárdenas

- Juan de la Cruz "Cotó" Antomarchi

- Carlos Godínez

- Nelson González

- Chito Latamblé

- Nené Manfugás (es)

- Juanito Márquez

- Isaac Oviedo

- Papi Oviedo

- Efraín Ríos

- Niño Rivera

- Arsenio Rodríguez

- Charlie Rodríguez

- Eliseo Silveira

- Panchito Solares

- Senén Suárez (es)

- Victor Trias

Notable performers of the Puerto Rican tres include:[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Orovio, Helio (2004). Cuban Music from A to Z. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9780822385219.

- ^ a b Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal (2006). Los contrapuntos de la música cubana (in Spanish). San Juan, PR: Ediciones Callejón. pp. 312–317. ISBN 9781881748489.

- ^ Lapidus, Benjamin (2008). Origins of Cuban Music and Dance: Changüí. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781461670292.

- ^ Orovio, Helio (La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, [1981] 1992). Diccionario de la Musica Cubana. p. 481.

- ^ a b c Sánchez de Fuentes, Eduardo (1927). Anales de la Academia Nacional de Artes y Letras Vols. 11-12 (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Cárdenas y Cía. p. 149.

- ^ a b c d e Ortiz, Fernando (1955). Los instrumentos de la música afrocubana: Los pulsativos, los fricativos, los insuflativos y los aeritivos (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Dirección de Cultura del Ministerio de Educación. p. 60.

- ^ Carpentier, Alejo (1987). "La música en Cuba". Ese músico que llevo dentro 3 - La música en Cuba (in Spanish). Mexico DF: Siglo XXI. p. 242. ISBN 9789682314131.

- ^ Amador, Efraín (2005). Universalidad del laúd y el tres cubano (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 100.

- ^ Hernández Fusté, Yelanys (12 December 2010). "Otorgan a Pancho Amat el Premio Nacional de Música". Juventud Rebelde (in Spanish). Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ The Stringed Instrument Database

- ^ Pena, Joel (2007). Fun with Cuban Tres. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. ISBN 978-0-7866-7292-9.

- ^ Lapidus (2008). p. 18.

- ^ Betancourt Molina, Lino (3 April 2013). "El armónico de Compay Segundo". Cubarte (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Ochoa, Eliades (16 December 2016). "Mi guitarra tres". EliadesOchoa.com. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Lapidus (2008). p. 16-18.

- ^ Shepherd, John; Horn, David (2014). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 9. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 535. ISBN 9781441132253.

- ^ Lapidus (2008). p. 51.

- ^ Grupo Changüí de Guantánamo (1983). Ahora sí. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba: Siboney.

- ^ Lapidus (2008). p. 96.

- ^ González, Leonel "Guajiro"; Griffin, Jon (2012). Cuban Masters Series: The Cuban Tres. US: Salsa Blanca Publishing. p. 535. ISBN 9781941837351.

- ^ From an interview with Jon Griffin, Havana, Cuba, 2013.

- ^ Moore, Kevin (2010). Beyond Salsa Piano; The Cuban Timba Piano Revolution v.1 The Roots of Timba Tumbao p. 17. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com.

- ^ Moore, Kevin (2010). Beyond Salsa Piano v.1 p. 32. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN 1439265844.

- ^ Lapidus (2008). p. 56.

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2011) Rumba Quinto. p. xiv. Redway, CA: Bembe Books. ISBN 1-4537-1313-1

- ^ Tejeda, Darío; Yunén, Rafael Emilio (2008). El son y la salsa en la identidad del Caribe (in Spanish). Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic: Centro León. p. 441. ISBN 9789945859676.

- ^ Gómez, Ramón. "El vínculo del tres cubano y el tres puertorriqueño". Proyecto del Cuatro Puertorriqueño (in Spanish). Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Amador, Efraín (2005). Universalidad del laúd y el tres cubano (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 10.

- ^ Giro, Radamés (1997). Visión panorámica de la guitarra en Cuba (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 51.

- ^ a b González, Nelson (2006). Tres Guitar Method. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9781609745868.

Further reading

[edit]- Books

- Richards, Tobe A. (2007). The Tres Cubano Chord Dictionary: C Major Tuning 648 Chords. United Kingdom: Cabot Books. ISBN 978-1-906207-03-8. — A comprehensive chord dictionary instructional guide.

- Richards, Tobe A. (2007). The Tres Cubano Chord Dictionary: D Major Tuning 648 Chords. United Kingdom: Cabot Books. ISBN 978-1-906207-04-5. — A comprehensive chord dictionary instructional guide.

- Griffin, Jon (2007). El tres cubano. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-8256-3324-9. — An instructional guide (in Spanish and English)

- Online resources

- The Tres in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican Cuatro Project.

- Burns, Sheila (19 May 2009). Havana: The Music of the Cricket. The Guardian.

- Echarry, Irina (7 May 2009) Tres Magic on Havana’s Malecon . Havana Times.

- Griffin, Jon. Cuban Tres - The 3 String Guitar Instrument from Cuba. Salsa Blanca.