Treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions.[1] A monograph is a treatise on a specialized topic.[2]

Etymology

[edit]The word "treatise" has its origins in the early 14th century, derived from the Anglo-French term tretiz, which itself comes from the Old French traitis, meaning "treatise" or "account." This Old French term is rooted in the verb traitier, which means "to deal with" or "to set forth in speech or writing".[3]

The etymological lineage can be traced further back to the Latin word tractatus, which is a form of the verb tractare, meaning "to handle," "to manage," or "to deal with".[4][5] The Latin roots suggest a connotation of engaging with or discussing a subject in depth, which aligns with the modern understanding of a treatise as a formal and systematic written discourse on a specific topic.[6]

Historically significant treatises

[edit]Table

[edit]The works presented here have been identified as influential by scholars on the development of human civilization.

Discussion

[edit]Euclid's Elements

[edit]Euclid's Elements has appeared in more editions than any other books except the Bible and is one of the most important mathematical treatises ever. It has been translated to numerous languages and remains continuously in print since the beginning of printing. Before the invention of the printing press, it was manually copied and widely circulated. When scholars recognized its excellence, they removed inferior works from circulation in its favor. Many subsequent authors, such as Theon of Alexandria, made their own editions, with alterations, comments, and new theorems or lemmas. Many mathematicians were influenced and inspired by Euclid's masterpiece. For example, Archimedes of Syracuse and Apollonius of Perga, the greatest mathematicians of their time, received their training from Euclid's students and his Elements and were able to solve many open problems at the time of Euclid. It is a prime example of how to write a text in pure mathematics, featuring simple and logical axioms, precise definitions, clearly stated theorems, and logical deductive proofs. The Elements consists of thirteen books dealing with geometry (including the geometry of three-dimensional objects such as polyhedra), number theory, and the theory of proportions. It was essentially a compilation of all mathematics known to the Greeks up until Euclid's time.[10]

Maxwell's Treatise

[edit]Drawing on the work of his predecessors, especially the experimental research of Michael Faraday, the analogy with heat flow by William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) and the mathematical analysis of George Green, James Clerk Maxwell synthesized all that was known about electricity and magnetism into a single mathematical framework, Maxwell's equations. Originally, there were 20 equations in total. In his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism (1873), Maxwell reduced them to eight.[11] Maxwell used his equations to predict the existence of electromagnetic waves, which travel at the speed of light. In other words, light is but one kind of electromagnetic wave. Maxwell's theory predicted there ought to be other types, with different frequencies. After some ingenious experiments, Maxwell's prediction was confirmed by Heinrich Hertz. In the process, Hertz generated and detected what are now called radio waves and built crude radio antennas and the predecessors of satellite dishes.[12] Hendrik Lorentz derived, using suitable boundary conditions, Fresnel's equations for the reflection and transmission of light in different media from Maxwell's equations. He also showed that Maxwell's theory succeeded in illuminating the phenomenon of light dispersion where other models failed. John William Strutt (Lord Rayleigh) and Josiah Willard Gibbs then proved that the optical equations derived from Maxwell's theory are the only self-consistent description of the reflection, refraction, and dispersion of light consistent with experimental results. Optics thus found a new foundation in electromagnetism.[11]

Hertz's experimental work in electromagnetism stimulated interest in the possibility of wireless communication, which did not require long and expensive cables and was faster than even the telegraph. Guglielmo Marconi adapted Hertz's equipment for this purpose in the 1890s. He achieved the first international wireless transmission between England and France in 1900 and by the following year, he succeeded in sending messages in Morse code across the Atlantic. Seeing its value, the shipping industry adopted this technology at once. Radio broadcasting became extremely popular in the twentieth century and remains in common use in the early twenty-first.[12] But it was Oliver Heaviside, an enthusiastic supporter of Maxwell's electromagnetic theory, who deserves most of the credit for shaping how people understood and applied Maxwell's work for decades to come; he was responsible for considerable progress in electrical telegraphy, telephony, and the study of the propagation of electromagnetic waves. Independent of Gibbs, Heaviside assembled a set of mathematical tools known as vector calculus to replace the quaternions, which were in vogue at the time but which Heaviside dismissed as "antiphysical and unnatural."[13]

See also

[edit]- Compilation thesis

- Edited volume

- Legal treatise

- Tractate

- Tractatus

- Thesis (Dissertation)

- Academic publishing

- Collection of articles

References

[edit]- ^ "Treatise." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Accessed September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Monograph." Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Accessed September 12, 2020.

- ^ "treatise | Etymology of treatise by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ "treatise | Etymology of treatise by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ "Treatise Definition & Meaning | YourDictionary". www.yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

- ^ Publishers, HarperCollins. "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: treatise". ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 2024-08-11.

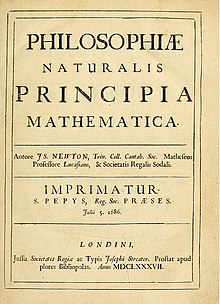

- ^ J. M. Steele, University of Toronto, (review online from Canadian Association of Physicists) Archived 1 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine of N. Guicciardini's "Reading the Principia: The Debate on Newton's Mathematical Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736" (Cambridge UP, 1999), a book which also states (summary before title page) that the "Principia" "is considered one of the masterpieces in the history of science".

- ^ (in French) Alexis Clairaut, "Du systeme du monde, dans les principes de la gravitation universelle", in "Histoires (& Memoires) de l'Academie Royale des Sciences" for 1745 (published 1749), at p. 329 (according to a note on p. 329, Clairaut's paper was read at a session of November 1747).

- ^ G. E. Smith, "Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2008 Edition), E. N. Zalta (ed.).

- ^ Katz, Victor (2009). "Chapter 3: Euclid". A History of Mathematics – An Introduction. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-38700-4.

- ^ a b Baigrie, Brian (2007). "Chapter 9: The Science of Electromagnetism". Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33358-3.

- ^ a b Baigrie, Brian (2007). "Chapter 10: Electromagnetic Waves". Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective. United States of America: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33358-3.

- ^ Hunt, Bruce (November 1, 2012). "Oliver Heaviside: A first-rate oddity". Physics Today. 65 (11): 48–54. Bibcode:2012PhT....65k..48H. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1788.

External links

[edit] Media related to Treatises at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Treatises at Wikimedia Commons