Torpedo...Los!

| Torpedo...Los! | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Roy Lichtenstein |

| Year | 1963 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Movement | Pop art |

| Dimensions | 173.4 cm × 204 cm (68.3 in × 80 in) |

| Location | Private collection |

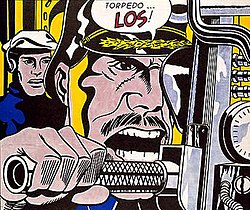

Torpedo...Los! (sometimes Torpedo...LOS!) is a 1963 pop art oil on canvas painting by Roy Lichtenstein. When it was last sold in 1989, The New York Times described the work as "a comic-strip image of sea warfare".[1] It formerly held the record for the highest auction price for a Lichtenstein work. Its 1989 sale helped finance the construction of the current home of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 1991.

Like many of Lichtenstein's works its title comes from the speech balloon in the painting. The work was included in Lichtenstein's second solo exhibition. The source of the image is a comic book from DC Comics. Lichtenstein has made significant alterations to the original image to change the focus and perspective in addition to significant alteration of the narrative element of the work. The work plays on the background-foreground relationship and the theme of vision that appears in many of Lichtenstein's works.

Background

[edit]

The source of the image is Jack Abel's art in the Bob Haney-written story "Battle of the Ghost Ships?", in DC Comics' Our Fighting Forces #71 (October 1962), although the content of the speech balloon is different.[2][3][4] According to the Lichtenstein Foundation website, Torpedo...Los! was part of Lichtenstein's second solo exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery of September 28 – October 24, 1963, that included Drowning Girl, Baseball Manager, In the Car, Conversation, and Whaam![5][6] Marketing materials for the show included the lithograph artwork, Crak![7][8]

On November 7, 1989, Torpedo...Los! sold at Christie's for $5.5 million (US$13.5 million in 2023 dollars[9]) to Zurich dealer Thomas Ammann, which was a record for a work of art by Lichtenstein.[1] The sale was described as the "highpoint" of a night in which Christie's achieved more than double the total sales prices of any other contemporary art auction up to that date.[10] The seller of the work was Beatrice C. Mayer, the widow of Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago founder and board member Robert B. Mayer as well as daughter of Sara Lee Corporation founder Nathan Cummings.[11][12] Prior to the sale the work was part of the Robert B. Mayer Memorial Loan Program and was exhibited at colleges and museums.[11] Torpedo...Los! was expected to sell for $3 to 4 million at the time.[11] In 1991, Mayer became one of the key benefactors of the new Museum of Contemporary Art Building.[13]

Description

[edit]Measuring 68 by 80 inches (172.7 cm × 203.2 cm), Torpedo...Los! is an oil on canvas painting.[4] By enlarging the face of the captain relative to the entire field, Lichtenstein makes him more prominent than in the source.[3] He retained the source's "clumsiness" in how the secondary figure is presented and replaced the dialogue with a much shorter "cryptic command".[3] The original source had dialog related to the repeated torpedoing of the same ship, but Lichtenstein cut the entire speech balloon down to two words. He moved the captain's scar from his nose to his cheek and he made the captain appear more aggressive by depicting him with his mouth wide open, also opting to leave the eye which was not looking through the periscope open. He also made the ship appear to be more technologically sophisticated with a variety of changes.[14] The scar was actually most readily apparent in panels other than the source from the same story.[15]

This work exemplifies Lichtenstein's theme relating to vision. Lichtenstein uses a "mechanical viewing device" to present his depiction of technically aided vision.[16][17] The depicted mechanical device, a periscope in this case, forces the vision into a monocular format.[18] In some of his works such as this, monocularity is a strong theme that is directly embodied although only by allusion.[19] Michael Lobel notes that "...his work proposes a dialectical tension between monocular and binocular modes of vision, a tension that operates on the level of gender as well."[20] The work is regarded as one in which Lichtenstein exaggerated comic book sound effects in common pop art style.[21]

Reception

[edit]This painting exemplifies Lichtenstein's use of the background/foreground shift and ironic colloquialisms in critical commands.[22] Although most of Lichtenstein's war imagery depicts American war themes, this depicts "a scarred German submarine captain at a battle station".[23] The manner of depiction with the commander's face pressed against the periscope reflects fusions of industrial art of the 1920s and 1930s.[24] The ironic aspect of this in 1963 is in part due to its temporal displacement referring back to World War II during the much later period of the Cold War.[25] The styling of the balloon content, especially that of the large font characters, is complemented by or complementary to the other traditional visual content of the painting.[26] Lichtenstein's alterations heightened the sense of urgency in the image, however, they also offset that menace by forming a detached work.[14] A November 1963 Art Magazine review stated that this was one of the "broad and powerful paintings" of the 1963 exhibition at Castelli's Gallery.[6]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Reif, Rita (November 9, 1989). "A de Kooning Work Sets A Record at $20.7 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ Our Fighting Forces #71 at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ a b c Waldman 1993, pp. 96–97, 104

- ^ a b "Torpedo...LOS!". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Chronology". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Judd, Donald. "Reviews 1962–64". In Bader (ed.). Roy Lichtenstein: October Files. pp. 2–4.

- ^ "Search Result: CRAK!". LichtensteinFoundation.org. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Lobel, Michael (2009). "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity". In Bader, Graham (ed.). Roy Lichtenstein. October Files. MIT Press. pp. 118–20. ISBN 978-0-262-01258-4.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Reif, Rita (December 6, 1989). "Art Prices Are Still Astonishing, But Fever Seems to Be Cooling". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c Reif, Rita (November 3, 1989). "Auctions". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ Gillespie, Mary (January 29, 1991). "Donors cite need for new art museum". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ Gillespie, Mary (January 29, 1991). "Trustees endow success of a new art museum". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Shanes, Eric (2009). "The Plates". Pop Art. Parkstone Press International. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-84484-619-1.

- ^ Lobel 2009, p. 117, "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity"

- ^ Lobel, Michael (2003). "Pop according To Lichtenstein". In Holm, Michael Juul; Poul Erik Tøjner; Martin Caiger-Smith (eds.). Roy Lichtenstein: All About Art. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. p. 85. ISBN 87-90029-85-2.

- ^ Lobel 2009, p. 120, "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity", "Like Torpedo...LOS! and CRAK!, each of these works contains the image of a mechanical aid to vision."

- ^ Lobel 2009, p. 119, "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity"

- ^ Lobel 2009, p. 116, "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity"

- ^ Lobel 2009, p. 118, "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity"

- ^ Brooker, Will (2001). Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 182. ISBN 0826413439. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- ^ Waldman 1993, p. 97

- ^ Coplans, John, ed. (1972). Roy Lichtenstein. Praeger Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 0713907614.

- ^ Hendrickson, Janis (1993). "The Pictures That Lichtenstein Made Famous, or The Pictures That Made Lichtenstein Famous". Roy Lichtenstein. Benedikt Taschen. p. 38. ISBN 3-8228-9633-0.

- ^ Frascina, Francis, ed. (2000). Pollack and After: The Critical Debate (second ed.). Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 0-415-22867-0.

- ^ Madoff, Steven Henry, ed. (1997). "Focus: The Major Artists". Pop Art: A Critical History. University of California Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-520-21018-2.

References

[edit]- Bader, Graham, ed. (2009). Roy Lichtenstein: October Files. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01258-4.

- Waldman, Diane (1993). "War Comics, 1962–64". Roy Lichtenstein. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. ISBN 0-89207-108-7.