Murder of Shanda Sharer

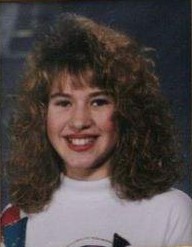

Victim Shanda Sharer c. November 1991 | |

| Date | January 11, 1992 |

|---|---|

| Location | Madison, Indiana, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′56.7″N 85°19′10.2″W / 38.899083°N 85.319500°W |

| Type | Child-on-child murder by immolation, torture murder, stabbing, beating, ligature strangulation, sexual assault, kidnapping, arson |

| Motive | Revenge against Sharer for dating Loveless' ex-girlfriend |

| Deaths | Shanda Renée Sharer, aged 12 |

| Convicted |

|

| Verdict | All four pleaded guilty |

| Convictions | Loveless, Tackett, Rippey: Murder, criminal confinement, arson Lawrence: Criminal confinement |

| Sentence | Loveless and Tackett: 60 years in prison (Loveless paroled after 26 years, Tackett paroled after 25 years) Rippey: 35 years in prison (paroled after 14 years) Lawrence: 20 years in prison (paroled after 9 years) |

Shanda Renée Sharer (June 6, 1979 – January 11, 1992) was an American girl who was tortured and burned to death in Madison, Indiana, by four teenage girls. She was 12 years old at the time of her death. The crime attracted international attention due to both its brutality and the young age of the perpetrators, who were aged between 15 and 17 years old. The case was covered on national news and talk shows and has inspired a number of episodes on fictional crime shows.[1]

Victim

[edit]Shanda Sharer was born in the Pineville Community Hospital in Pineville, Kentucky, on June 6, 1979, to Stephen Sharer and his wife Jacqueline, who was later known as Jacqueline (or Jacque) Vaught.[2] After Sharer's parents divorced, her mother remarried and the family moved to Louisville. There, Sharer attended fifth and sixth grades at St. Paul School, where she was on the cheerleading, volleyball, and softball teams.[3] When her mother divorced again, the family moved in June 1991 to New Albany, Indiana, and Sharer enrolled at Hazelwood Middle School.[4] Early in the school year, she transferred to Our Lady of Perpetual Help School, a Catholic school in New Albany, where she joined the girls' basketball team.[3]

Perpetrators

[edit]Melinda Loveless

[edit]Melinda Loveless was born in New Albany on October 28, 1975, the youngest of three daughters, to Marjorie and Larry Loveless. Larry was drafted into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, reaching the rank of sergeant, and although horribly emotionally scarred, he was treated as a hero upon his return. Marjorie later described him as a sexual deviant who would wear her and her daughters' underwear and makeup, was incapable of staying monogamous, and had a mixture of jealousy and fascination with seeing her have sex with other men and women. They lived in or near New Albany throughout Melinda's childhood.[5]

Larry worked irregularly for the Southern Railway after his military service; his profession allowed him to work whenever most convenient for him. In 1965, Larry became a probationary officer with the New Albany Police Department, but was fired after eight months when he and his partner assaulted an African-American man whom Larry accused of sleeping with his wife.[6] In 1988, Larry briefly worked as a mail carrier, but quit after three months and did very little work, having brought most of his mail home to destroy it.[7]

Marjorie had worked intermittently since 1974. When both parents were working, the family was financially well off, living in the upper-middle-class suburb of Floyds Knobs, Indiana. Larry, who was violent and abusive, did not usually share his income with the family and impulsively spent any money he earned on himself, usually purchasing firearms, motorcycles and cars. He filed for bankruptcy in 1980. Extended family members often described the Loveless marriage as loveless, and the daughters as visiting their homes hungry, apparently not getting enough food at home.[8]

The Loveless parents would often visit bars in Louisville, where Larry would pretend to be a doctor or a dentist and introduce Marjorie as his girlfriend. He would also "share" her with some of his friends from work, which she found disgusting. During an orgy with another couple at their house, Marjorie tried to commit suicide, an act she would repeat several times throughout her daughters' childhoods.[9] When Melinda was nine years old, Larry had Marjorie gang raped, after which she tried to drown herself. After that incident, she refused to have sex with him for a month until he raped her as their daughters overheard the event through a closed door. In the summer of 1986, after she would not let him go home with two women he met at a bar, Larry beat Marjorie so severely that she was hospitalized; he was convicted of battery.[10]

The extent of Larry's abuse of his daughters and other children is unclear. Various court testimonies claimed he fondled Melinda as an infant, molested Marjorie's 13-year-old sister early in the marriage, and molested the girls' cousin Teddy from age 10 to 14. Both older girls said he molested them, though Melinda did not admit this ever happened to her. She slept in bed with him until he abandoned his family when she was 14. In court, Teddy described an incident in which Larry tied all three sisters in a garage and raped them in succession; however, the sisters did not confirm this account. Larry was verbally abusive to his daughters and fired a handgun in the direction of Melinda's older sister Michelle when she was seven, intentionally missing her. He would also embarrass his children by finding their underwear and smelling it in front of other family members.[11]

For two years, beginning when Melinda was five, the family was deeply involved in the Graceland Baptist Church. Larry and Marjorie gave full confession and renounced drinking and swinging while they were members. Larry became a Baptist lay preacher and Marjorie became the school nurse. The church later arranged for Melinda to be taken to a motel room with a 50-year-old man for a five-hour exorcism. Larry became a marriage counselor with the church and acquired a reputation for being too forward with women, eventually attempting to rape one of them. After that incident, the Loveless parents left the church and returned to their former professions and drinking.[12]

In November 1990, after Larry was caught spying on Melinda and a friend, Marjorie attacked him with a knife; he was sent to the hospital after he attempted to grab it. She then attempted suicide again, and her daughters called authorities. After this incident, Larry filed for divorce and moved to Avon Park, Florida. Melinda felt crushed, especially when Larry remarried. He sent letters to her for a while, playing on her emotions, but eventually severed all contact with her. Larry was killed in a car crash in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 16, 1998.[7]

Laurie Tackett

[edit]Mary Laurine "Laurie" Tackett was born in Madison, Indiana, on October 5, 1974. Her mother was a fundamentalist Pentecostal Christian and her father was a factory worker with two felony convictions in the 1960s. Tackett claimed that she was molested at least twice as a child at ages 5 and 12. In May 1989, her mother discovered that Tackett was changing from a dress into jeans at school, and, after a confrontation that night, attempted to strangle her. Social workers became involved, and Tackett's parents agreed to unannounced visits to ensure that child abuse was not occurring.[13] Tackett and her mother came into periodic conflict; at one point, her mother went to Hope Rippey's house after learning that Rippey's father had purchased a Ouija board for the girls. She demanded that the board be burnt and that the Rippeys' house be exorcised.[14]

Tackett became increasingly rebellious after her 15th birthday and also became fascinated with the occult. She would often attempt to impress her friends by pretending to be possessed by the spirit of "Deanna the Vampire".[15] Tackett began to engage in self-harm, especially after early 1991 when she began dating a girl who was involved in the practice. Her parents discovered the self-mutilation and checked her into a hospital on March 19, 1991. She was prescribed an anti-depressant and released. Two days later, with her girlfriend and Toni Lawrence, Tackett cut her wrists deeply and was returned to the hospital. After treatment of her wound, she was admitted to the hospital's psychiatric ward.[16] Tackett was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and confessed that she had experienced hallucinations since she was a young child. She was discharged on April 12. She dropped out of high school in September 1991.[17]

Tackett stayed in Louisville in October 1991 to live with various friends. There she met Loveless; the two became friends in late November.[18] In December, Tackett moved back to Madison on the promise that her father would buy her a car. She still spent most of her time in Louisville and New Albany, and, by December, spent most of it with Loveless.[19]

Hope Rippey

[edit]Hope Anna Rippey was born in Madison on June 9, 1976.[20] Her father was an engineer at a power plant. Her parents divorced in February 1984, and she moved with her mother and siblings to Quincy, Michigan, for three years. She claimed that living with her family in Michigan was somewhat turbulent. Her parents resumed their relationship in Madison in 1987. She was reunited with friends Tackett and Toni Lawrence, whom she had known since childhood, although her parents saw Tackett as a bad influence.[21] As with the other girls, Rippey began to self-harm at age 15.[22]

Toni Lawrence

[edit]Toni Lawrence was born in Madison on February 14, 1976. Her father was a boilermaker. She was close friends with Rippey from childhood. She was abused by a relative at age 9 and was raped by a teenage boy at age 14, although the police only issued an order for the boy to keep away from Lawrence. She began attending counseling after the incident but did not continue. She became promiscuous, began to self-harm, and attempted suicide in eighth grade.[23]

Events prior to murder

[edit]In 1990, 14-year-old Loveless began dating another 14-year-old named Amanda Heavrin. After Loveless' father left the family and her mother remarried, Loveless began behaving increasingly erratically. She got into fights at school and reported being depressed, resulting in her receiving professional counseling. In March 1991, Loveless came out as a lesbian (as her two older sisters had done) to her mother. Her mother was initially furious but eventually accepted it. As the year progressed, Loveless's relationship with Heavrin deteriorated.[24]

Heavrin met Shanda Sharer early in the fall semester at Hazelwood Middle School when Heavrin started a fight with Sharer; however, they became friends while in detention for the altercation and later exchanged romantic letters. Loveless immediately grew jealous of Heavrin and Sharer's close friendship. In early October 1991, Heavrin took Sharer as her date to a school dance, where Loveless found and confronted Sharer. Although Heavrin and Loveless never actually broke up, Loveless started dating an older girl.[25]

After Heavrin and Sharer attended a festival together in late October, Loveless began to discuss killing Sharer and threatened her in public. Concerned about the effects of their daughter's relationship with Heavrin, Sharer's parents arranged for her to transfer to a Catholic school in late November.[26] Heavrin later claimed she gave letters Loveless sent her containing death threats towards Sharer to a "youth prosecutor", but the youth prosecutor never did anything about it as far as she knew.[27]

Events of January 10–11, 1992

[edit]Pre-abduction

[edit]On the night of January 10, 1992, Lawrence (age 15), Rippey (15) and Tackett (17) drove in Tackett's car from Madison to Loveless's house in New Albany. Rippey and Lawrence, while both friends of Tackett, had not previously met Loveless (16). Upon arrival, they borrowed some clothes from Loveless, and she showed them a knife, telling them she was going to scare Sharer with it. While Tackett, Rippey, and Lawrence had never met Sharer prior to that night, Tackett already knew of the plan to murder the 12-year-old girl. Loveless explained to the two other girls that she disliked Sharer for being a "copycat" and for stealing her girlfriend.[28]

Tackett let Rippey drive the four girls to Jeffersonville, where Sharer stayed with her father on the weekends, stopping at a McDonald's restaurant en route to ask for directions. They arrived at Sharer's house shortly before dark. Loveless instructed Rippey and Lawrence to go to the door and introduce themselves as friends of Heavrin. Sharer answered the door, and Rippey and Lawrence asked for Shanda, Sharer then replied that she was Shanda. Rippey and Lawrence asked Shanda to come with them to see Heavrin, who was waiting for them at "the Witch's Castle", or Mistletoe Falls, a ruined stone house located on an isolated hill overlooking the Ohio River.

Sharer was reluctant to go out, told them she had a party to attend, and suggested the girls come back around midnight, a few hours later.[29] Loveless was angry at first, but Rippey and Lawrence assured her about returning for Sharer later. The four girls crossed the river to Louisville and attended a punk rock show by the band Sunspring[30] at the Audubon Skate Park near Interstate 65. Lawrence and Rippey quickly lost interest in the music and went to the parking lot outside, where they engaged in sexual activities with two boys in Tackett's car.[31]

Eventually, the four girls left for Sharer's house. During the ride, Loveless said that she could not wait to kill Sharer; however, Loveless also said she just intended to use the knife to frighten her. When they arrived at Sharer's house at 12:30 a.m., Lawrence refused to retrieve Sharer, so Tackett went with Rippey to the door instead. Loveless hid under a blanket in the back seat of the car with the knife.[32]

Abduction

[edit]Sharer's father and stepmother had gone to bed and allowed Sharer to stay downstairs for a bit to watch television. Rippey told Sharer that Heavrin was still at the Witch's Castle. Sharer was reluctant to go with them, yet agreed after changing her clothes. As they got in the car, Rippey began asking Sharer questions about her relationship with Heavrin. Loveless then sprang out from the back seat, put the knife to Sharer's throat and began interrogating her about her sexual relationship with Heavrin. They drove towards Utica and the Witch's Castle. Tackett told the girls that a local legend said the house was once a castle owned by nine witches and that the townspeople burned down the house to get rid of the witches, leaving a small stone house in its place.[33]

At the Witch's Castle, they took a sobbing Sharer inside and bound her arms and legs with rope. There, Loveless taunted her, saying that she had pretty hair and wondered how pretty she would look if they were to cut it off, which frightened Sharer even more. Loveless began taking off Sharer's rings and handing them to the girls. At some point, Rippey took Sharer's Mickey Mouse watch and danced to the tune it played. Tackett further taunted Sharer, claiming that the Witch's Castle was filled with human remains and Sharer's would be next. To further threaten Sharer, Tackett then retrieved a shirt with a smiley design from the car and lit it on fire, but immediately feared that the fire would be spotted by passing cars, so the girls left with Sharer.

During the car ride, Sharer continued begging them to take her back home. Eventually, they became lost, so they stopped at a gas station and covered Sharer in a blanket. While Tackett went inside to ask for directions, Lawrence called a boy she knew in Louisville and chatted for several minutes to ease her worries, but did not mention Sharer's abduction. They returned to the car, but became lost again and pulled up to another gas station. There, Lawrence and Rippey spotted a couple of boys and talked to them before once again getting back into the car and leaving, arriving some time later at the edge of some woods near Tackett's home in Madison.[34]

Torture

[edit]Tackett led them to a dark abandoned building off a logging road in a densely forested area. Lawrence and Rippey were frightened and stayed in the car. Loveless and Tackett made Sharer strip down to her underwear; then, Loveless beat Sharer with her fists. Next, Loveless repeatedly slammed Sharer's face into her knee, which cut Sharer's mouth on her own braces. Loveless tried to slash Sharer's throat, but the knife was too dull. Rippey came out of the car to hold down Sharer. Loveless and Tackett took turns stabbing Sharer in the chest. They then strangled Sharer with a rope until she was unconscious, placed her in the trunk of the car, and told the other two girls that Sharer was dead.[35]

The girls drove to Tackett's nearby home and went inside to drink soda and clean themselves. When they heard Sharer screaming in the trunk, Tackett went out with a paring knife and stabbed her several more times, coming back a few minutes later covered with blood. After she washed, Tackett told the girls' futures with her "runestones". At 2:30 a.m., Lawrence and Rippey stayed behind as Tackett and Loveless went "country cruising", driving to the nearby town of Canaan. Sharer continued to make crying and gurgling noises, so Tackett stopped the car. When they opened the trunk, Sharer sat up, covered in blood with her eyes rolled back in her head, but unable to speak. Tackett beat her with a tire iron until she was silent, claiming that she felt Sharer's head caving in, and then told Loveless to "smell it". They also sexually assaulted Sharer with the same weapon. The tire-iron assault continued off and on for hours as the girls went on a joyride through the countryside.[36][37]

Loveless and Tackett returned to Tackett's house just before daybreak to clean up again and woke up the other two girls. Rippey asked about Sharer, and Tackett laughingly described the torture. The conversation woke up Tackett's mother, who was initially angry with her daughter for being out so late, but she also offered to cook the girls some breakfast. Tackett declined and said she needed to drive the other girls home. However, instead Tackett drove to the burn pile, where they opened the trunk to look at Sharer. Lawrence refused. Rippey suddenly sprayed Sharer with Windex and taunted, "You're not looking so hot now, are you?"[38]

Burned alive

[edit]

The girls drove to a gas station near Madison Consolidated High School, pumped some gasoline into the car, and bought a two-liter bottle of Pepsi. Tackett poured out the Pepsi and refilled the bottle with gasoline. They drove north of Madison, past Jefferson Proving Ground to Lemon Road off U.S. Route 421, a place known to Rippey. Lawrence remained in the car while Tackett and Rippey wrapped Sharer, who was still alive, in a blanket, and carried her to a field by the gravel country road. Rippey poured the gasoline on Sharer, and then they set her on fire. Loveless was not convinced Sharer was dead, so they returned a few minutes later to pour the rest of the gasoline on her.[39][40]

The girls went to a McDonald's restaurant at 9:30 a.m. for breakfast, where they laughed about Sharer's badly burned body looking like one of the sausages they were eating. Lawrence then phoned a friend and told her about the murder. Tackett then dropped off Lawrence and Rippey at their homes and finally returned to her own home with Loveless. Loveless told Heavrin that they had killed Sharer and arranged to pick up Heavrin later that day with Tackett.[41]

A friend of Loveless, Crystal Wathen, came over to Loveless's house, and they told her what had happened. Then, the three girls drove to pick up Heavrin and take her back to the Loveless home, where they told Heavrin the story. Both Heavrin and Wathen were reluctant to believe the story until Tackett showed them the trunk of the car with Sharer's bloody handprints and socks still present. Heavrin was horrified and asked to be taken home. When they pulled up in front of her house, Loveless kissed Heavrin, told her she loved her and pleaded with her not to tell anyone. Heavrin promised she would not before entering her house.[42]

Investigation

[edit]Later on the morning of January 11, 1992, two brothers from Canaan were driving toward Jefferson Proving Ground to go hunting when they noticed a body on the side of the road. They initially thought it was a mannequin of some sort, but upon exiting the vehicle realized that it was clearly the burned body of a child. They called the police at 10:55 a.m. and were asked to return to the corpse. State trooper David Camm and Jefferson County Sheriff Buck Shipley and detectives began an investigation, collecting forensic evidence at the scene. They initially suspected a drug deal gone wrong and did not believe the crime had been committed by locals. It is also to be noted that her body was posed in a suggestive position, very obviously meaning that this was done on purpose and with intention. It was also found that the victim's face and hands were burnt in an attempt to keep her unrecognizable and unidentifiable. She was found in the "pugilistic stance" with her arms outstretched, and clenched fists as a result of death by burning.[43]

Sharer's father, Steven, noticed his daughter was nowhere to be found early on January 11. After phoning neighbors and friends all morning, he called his ex-wife, Sharer's mother, at 1:45 p.m.; they met and filed a missing person report with the Clark County sheriff.[44][45]

At 8:20 p.m., a hysterical Lawrence and Rippey went to the Jefferson County Sheriff's office with their parents. They both gave very rambling statements, identifying the victim as "Shanda", naming the two other girls involved as best as they could, and describing the main events of the previous night. After an inter-county investigation, Shipley contacted the Clark County sheriff and was finally able to match the body to Sharer's missing person report.[46]

Detectives obtained dental records that positively identified Sharer as the victim.[47] Loveless and Tackett were arrested on January 12. The bulk of the evidence for the arrest warrant came from the statements made by Lawrence and Rippey. The prosecution immediately declared its intention to try both Loveless and Tackett as adults. For several months, the prosecutors and defense attorneys did not release any information about the case, giving the news media only the statements by Lawrence and Rippey.[45]

Judicial process

[edit]

| January 11, 1992 | Body of Shanda Sharer found in rural Jefferson County, Indiana |

|---|---|

| April 22, 1992 | Lawrence accepts plea bargain |

| September 21, 1992 | Loveless and Tackett accept plea bargains |

| January 4, 1993 | Loveless sentenced to 60 years |

| December 14, 2000 | Lawrence released on parole |

| November 3, 2004 | A judge reduces Rippey's 60-year sentence to 35 years |

| April 28, 2006 | Rippey released on parole |

| January 11, 2018 | Tackett released on parole |

| September 5, 2019 | Loveless released on parole |

All four girls were charged as adults. To avoid the death penalty, the girls accepted plea bargains.[48]

Mitigating factors

[edit]Some of the girls had troubled home lives, with claims of physical or sexual abuse committed by a parent or other adult. Lawrence, Rippey, and Tackett all had histories of self-harm.[49] Tackett was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and suffering from hallucinations.[17] Loveless, often described as the ringleader in the attack,[50] had the most extensive history of abuse and mental health issues.

Sentences

[edit]Tackett and Loveless were sentenced to 60 years in the Indiana Women's Prison in Indianapolis. Tackett was released in January 2018, and served probation for one year. Loveless was released in September 2019.[51] Rippey was sentenced to 60 years, with 10 years suspended for mitigating circumstances, plus 10 years of medium-supervision probation. On appeal, a judge reduced the sentence to 35 years. In exchange for her cooperation, Lawrence was allowed to plead guilty to one count of criminal confinement and was sentenced to a maximum of 20 years.

Appeals

[edit]Loveless appealed her sentence, but it was upheld by the Indiana Supreme Court in 1994.[52]

In October 2007, Loveless's attorney, Mark Small, sought post-conviction relief from the Jefferson Circuit Court that originally sentenced her. He argued that Loveless had been "profoundly retarded" by childhood abuse. Moreover, she had not been represented competently by counsel during her sentencing, which caused her to accept a plea bargain in the face of exaggerated claims about her chances of receiving the death penalty. Small also argued that Loveless, who was 16 years old when she signed the plea agreement, was too young to enter into a contract in the state of Indiana without consent from a parent or guardian, which had not been obtained. If the judge accepted these arguments, Loveless could have been retried or released outright.[53]

On January 8, 2008, Loveless's request was rejected by Jefferson Circuit Judge Ted Todd. Instead, Loveless would be eligible for parole in 15 years, thus maintaining the original guilty plea.[54] On November 14, 2008, Loveless's appeal was denied by the Indiana Court of Appeals, upholding Judge Todd's ruling.[55] Small stated that he would seek to have jurisdiction over the case moved to the Indiana Supreme Court.[56]

Releases

[edit]Lawrence was released on December 14, 2000, after serving nine years. She remained on parole until December 2002.[57]

On April 28, 2006, Rippey was released from Indiana Women's Prison on parole after serving 14 years of her original sentence. She remained on supervised parole for 5 years until April 2011.[58]

Tackett was released from Rockville Correctional Facility on January 11, 2018, the 26th anniversary of Sharer's death, after serving nearly 26 years, and has completed an additional year of parole.[59]

Loveless was released from Indiana Women's Prison on September 5, 2019.[60] After serving 26+ years in prison, she will serve parole in Jefferson County, Kentucky.

Aftermath

[edit]During Loveless's sentencing hearing, extensive open court testimony revealed that her father Larry had abused his wife, his daughters, and other children. Consequently, he was arrested in February 1993 on charges of rape, sodomy, and sexual battery. Most of the crimes occurred from 1968 to 1977. Larry remained in prison for over two years awaiting trial; however, a judge eventually ruled that all charges except one count of sexual battery had to be dropped due to the statute of limitations, which was five years in Indiana. Larry pleaded guilty to the one count of sexual battery. He received a sentence of time served and was released in June 1995.[61][62] A few weeks following his release, Larry unsuccessfully sued the Floyd County Jail for $39 million in federal court, alleging he had suffered cruel and unusual punishment during his two-year incarceration. Among his complaints were that he was not allowed to sleep in his bed during the day or to read the newspaper.[62]

Sharer's father, Steven Sharer, died of alcoholism in 2005 at the age of 53. In an interview with Shanda Sharer's mother, Jacque Vaught, on the Investigation Discovery series Deadly Women, Vaught stated that Sharer's father was so distraught by his daughter's murder that he "did everything he could to kill himself besides put a gun to his head" and that he "drank himself to death. The man definitely died from a broken heart".[63]

The Shanda Sharer Scholarship Fund was established in January 2009. The fund planned to provide scholarships to two students per year from Prosser School of Technology in New Albany; one scholarship to a student who is continuing his or her education, and the other scholarship to a student who is beginning his or her career and must buy tools or other work equipment.[64] By November 2018 Shanda's mother Jacque Vaught stated that the scholarship fund had been depleted and is no longer accepting donations.

In 2012, Jacque Vaught made her first contact with Melinda Loveless since the trials although indirectly. Vaught donated a dog named Angel in Shanda's name to Loveless to train for the Indiana Canine Assistance Network program (ICAN) through Project2heal, which provides service pets to people with disabilities. Loveless trained dogs for the program for several years. Vaught reported that she had endured criticism over the decision but defends it, saying, "It's my choice to make. She's [Shanda] my child. If you don't let good things come from bad things, nothing gets better. And I know what my child would want. My child would want this." Vaught stated that she hoped to donate a dog every year in honor of Shanda Sharer.[65] A documentary produced by Episode 11 Productions, titled Charlie's Scars, captured Vaught's decision to allow Loveless to train dogs in Shanda's name. The film also has three interviews with Loveless.

In popular culture

[edit]In literature and stage plays

[edit]The crime was documented in two true crime books, Little Lost Angel by Michael Quinlan[30] and Cruel Sacrifice by Aphrodite Jones;[66] Jones's book on the case became a New York Times Bestseller.

The story was turned into a play by Rob Urbinati called Hazelwood Jr. High, which starred Chloë Sevigny as Tackett.[67] The play was published by Samuel French, Inc. in September 2009.[68]

The 2023 novel Penance by Eliza Clark, which is structured as a fictional true crime book, centers on a murder with details and characters largely based on the murder of Shanda Sharer.[69]

The poem In God's Arms by author Lacy Gray was dedicated to the family of Shanda Renée Sharer. It was published on February 8, 1993, and May 11, 1995, in the Jeffersonville Evening News.[70] The 2008 book kissing dead girls includes the Daphne Gottlieb poem The Whole World Is Singing, told from the point of view of Shanda Sharer and includes lines from notes written from Sharer to Amanda Heavrin.[71]

On television

[edit]"Mean", an episode from the fifth season of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, is based on the murder.[72][73]

The Cold Case second-season episode "The Sleepover" is loosely based on this crime.[74]

In May 2011, Dr. Phil aired a two-part series on the crime, which featured Shanda Sharer's mother and sister Paije, who both harshly confronted Hope Rippey on the show about her early release, and an interview with Amanda Heavrin.[75]

The murder of Sharer was covered in the first of two segments in the Lifetime series Killer Kids, episode "Jealousy", aired: July 2014.[76][77]

The Investigation Discovery series The 1990s: The Deadliest Decade, episode "The New Girl" interviews Sharer's mother along with lead police officers, aired: November 2018.[78]

In art

[edit]American artist Marlene McCarty used the Shanda Sharer murder as one of the subjects for her Murder Girls series of drawings about teenage female murderers, their sexuality and their relationships.[79] McCarty's drawing titled Melinda Loveless, Toni Lawrence, Hope Rippey, Laurie Tackett, and Shanda Sharer – January 11, 1992 (1:39 am) (2000–2001) is now in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.[80]

See also

[edit]- Child murder

- List of kidnappings

- List of solved missing person cases: pre-2000

- Murder of Bobby Kent

- Murder of Michele Avila

- Murder of Skylar Neese

- Murder of Suzanne Capper

- Murder of Sylvia Likens

- Parker–Hulme murder case

- Slender Man stabbing

References

[edit]- ^ MacDonald, Janelle (May 20, 2011). "Shana Sharer's mother to appear on Dr. Phil". WAVE 3 News. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Aphrodite (1994). Cruel Sacrifice. Pinnacle. p. 46. ISBN 9780786010639.

- ^ a b Runquist, Pam (January 14, 1992). "The Pain of Remembering". The Courier-Journal. p. 8A.

- ^ Jones, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Jones, pp. 53–57.

- ^ Jones, pp. 59–66.

- ^ a b Jones, pp. 110–117.

- ^ Jones, pp. 71–77.

- ^ Jones, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Jones, pp. 87–98.

- ^ Jones, pp. 77–98.

- ^ Jones, pp. 78–85, 87.

- ^ Jones, pp. 158–163.

- ^ Jones, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Jones, pp. 164–167.

- ^ Jones, pp. 174–178.

- ^ a b Jones, pp. 179–188.

- ^ Jones, pp. 154–158.

- ^ Jones, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Sharer murderer Rippey to be freed from prison madisoncourier.com Retrieved 19 June 2019

- ^ Jones, pp. 168–171.

- ^ Jones, p. 178.

- ^ Jones, pp. 172–174.

- ^ Jones, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Jones, pp. 138–141.

- ^ Jones, pp. 142–152.

- ^ TrueCrimeVideos (May 28, 2011). "Amanda Heavrin Speaks About Shanda Sharer - In Cold Blood: A Daughter's Brutal Murder". Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jones, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Jones, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Quinlan, Michael (2012). Little Lost Angel. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1451698794.

- ^ Jones, p. 13.

- ^ Jones, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Jones, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Jones, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Jones, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Jones, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Lohr, David. "Death of Innocence - The Murder of Young Shanda Sharer". Crimelibrary.com. Chapter 9 Dead?. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Jones, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jones, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Lewis, Bob (January 31, 1993). "Thinking the Unthinkable: What Led 4 Teens to Torture, Murder Child?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Jones, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Jones, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Jones, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Jones, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Yetter, Deborah (January 13, 1992). "Teen Girls Charged in Torture Slaying of New Albany Girl". The Courier-Journal. p. 1A.

- ^ Jones, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Jones, p. 50.

- ^ Grossman, Ron (January 8, 1993). "On July 29, Tempo reported a case". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Jones, pp. 172–178.

- ^ MacDonald, Janelle (January 8, 2008). "Judge denies Loveless' request for early release in torture-killing". Wave 3 News. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Courtney Shaw (January 11, 2018). "Woman convicted in 1992 murder released from prison". WLKY.

- ^ Loveless v. State, 642 N.E.2d 974 (Indiana 1994-11-17).

- ^ Mojica, Stephanie (October 14, 2007). "Loveless seeks release from jail". The Tribune (New Albany). Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "Woman's torture-murder sentence stands". Associated Press. January 8, 2008. Archived from the original on January 30, 2008.

- ^ Loveless v. State, 896 N.E.2d 918 (Ind. Ct. App. 2008-11-14).

- ^ "Appeal denied in 1992 torture death". WLFI-TV. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009.

- ^ Lohr, David. "Death of Innocence - The Murder of Young Shanda Sharer". Crimelibrary.com. Chapter 17 Aftermath. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Lohr, David. "Death of Innocence - The Murder of Young Shanda Sharer". Crimelibrary.com. Chapter 22 "She is just Evil". Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Shaw, Courtney (January 11, 2018). "Woman convicted in 1992 murder released from prison". wlky.com. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Team, WLKY Digital (September 5, 2019). "Mastermind behind brutal murder of Indiana girl in 1992 released from prison". WLKY. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Pillow, John C. (February 3, 1995). "Fate Of Loveless Sex-Abuse Case Unclear Two Years After Arrest". The Courier-Journal. p. B1.

- ^ a b Pillow, John C. (June 21, 1995). "Inmates' Suit Nears Hearing". The Courier-Journal. p. B1.

- ^ Paul, Hawker (December 24, 2008). "Thrill Killers". Deadly Women. Season 2. Episode 1. Discovery Channel.

- ^ Dunn, Trisha (January 11, 2009). "New Albany memorial focuses on Shanda, not her murder". News and Tribune. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Ryder, Anne (May 21, 2012). "Shanda Sharer's mother and murderer form unlikely alliance". WAVE 3 News. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Aphrodite (1999). Cruel Sacrifice. Pinnacle. ISBN 9780786010639.

- ^ Evans, Greg (May 6, 1998). "Review: 'Hazelwood Jr. High'". Variety. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Urbinati, Rob (2009). Hazelwood Jr. High. Samuel French, Inc. ASIN B008MR6DHW.

- ^ Cummins, Anthony (June 24, 2023). "Eliza Clark: 'I'm more primary school teacher than enfant terrible'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ "In God's Arms". lacygray.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Gottlieb, Daphne (2008). kissing dead girls. Soft Skull Press. ISBN 978-0979663659.

- ^ Dwyer, Kevin; Fiorillo, Jure (2007). True Stories of Law & Order. Berkley Trade. pp. 32–36. ISBN 9780425217351.

- ^ Fazekas, Michele; Butters, Tara (February 24, 2004). "Mean". Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. Season 5. Episode 17. CBS.

- ^ Garcia, Liz W. (November 7, 2004). "The Sleepover". Cold Case. Season 2. Episode 6. CBS.

- ^ "In Cold Blood: A Daughter's Brutal Murder". Dr. Phil. May 20, 2011.

- ^ "Killer Kids - Season 3 Episodes List". next-episode.net. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "Watch Jealousy Full Episode - Killer Kids | Lifetime". Lifetime. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "The 1990s: The Deadliest Decade |". TVGuide.com. Discovery Communications Inc. November 12, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Honigmann, Ana Finel (August 2013). "Sex and Death: Interview with Marlene McCarty". Artslant. Worldwide: Artslant.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ "MOCA Collection: Marlene McCarty: 2000–2001: Melinda Loveless, Toni Lawrence, Hope Rippey, Laurie Tackett, and Shanda Sharer – January 11, 1992 (1:39 am)". moca.org. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA). Retrieved February 5, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Charlie's Scars Archived September 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine - Documentary related to Shanda Sharer

- Lohr, David. "The Killing Field." Crime Library

- Video about Shanda Sharer murder on YouTube

- 1990s missing person cases

- 1992 in Indiana

- 1992 murders in the United States

- 1993 in Indiana

- 20th-century American trials

- Crimes in Indiana

- Deaths by person in Indiana

- Deaths from fire in the United States

- Female criminal duos

- Female juvenile murderers

- Female murder victims

- Formerly missing people

- History of Indiana

- Incidents of violence against girls

- January 1992 crimes in the United States

- Kidnapped American children

- Madison, Indiana

- Missing person cases in Indiana

- Murder committed by minors

- Murder in Indiana

- Violence against LGBTQ people in the United States

- Violence against LGBTQ women

- Violence against women in Indiana

- Child murder in the United States