Toll road

A toll road, also known as a turnpike or tollway, is a public or private road for which a fee (or toll) is assessed for passage. It is a form of road pricing typically implemented to help recoup the costs of road construction and maintenance.

Toll roads have existed in some form since antiquity, with tolls levied on passing travelers on foot, wagon, or horseback; a practice that continued with the automobile, and many modern tollways charge fees for motor vehicles exclusively. The amount of the toll usually varies by vehicle type, weight, or number of axles, with freight trucks often charged higher rates than cars.

Tolls are often collected at toll plazas, toll booths, toll houses, toll stations, toll bars, toll barriers, or toll gates. Some toll collection points are automatic, and the user deposits money in a machine which opens the gate once the correct toll has been paid. To cut costs and minimise time delay, many tolls are collected with electronic toll collection equipment which automatically communicates with a toll payer's transponder or uses automatic number-plate recognition to charge drivers by debiting their accounts.

Criticisms of toll roads include the time taken to stop and pay the toll, and the cost of the toll booth operators—up to about one-third of revenue in some cases. Automated toll-paying systems help minimise both of these. Others object to paying "twice" for the same road, namely in fuel taxes and in tolls.

In addition to toll roads, toll bridges and toll tunnels are also used by public authorities to generate funds to repay the cost of building the structures. Some tolls are set aside to pay for future maintenance or enhancement of infrastructure, or are applied as a general fund by local governments, not being earmarked for transport facilities. This is sometimes limited or prohibited by central government legislation. Also, road congestion pricing schemes have been implemented in a limited number of urban areas as a transportation demand management tool to try to reduce traffic congestion and air pollution.[1]

History

[edit]

Ancient times

[edit]Toll roads have existed for at least the last 2,700 years, as tolls had to be paid by travellers using the Susa–Babylon highway under the regime of Ashurbanipal, who reigned in the seventh century BC.[2]

Aristotle and Pliny refer to tolls in Arabia and other parts of Asia. In India, before the fourth century BC, the Arthashastra notes the use of tolls. Germanic tribes charged tolls to travellers across mountain passes.

Middle Ages

[edit]Most roads were not freely open to travel on in Europe during the Middle Ages,[3] and the toll was one of many feudal fees paid for rights of usage in everyday life. Some major European "highways", such as the Via Regia and Via Imperii, offered protection to travelers in exchange for paying the royal toll.

Many modern European roads were originally constructed as toll roads in order to recoup the costs of construction and maintenance, and to generate revenue from passing travelers. In 14th-century England, some of the most heavily used roads were repaired with money raised from tolls by pavage grants. Widespread toll roads sometimes restricted traffic so much, by their high tolls, that they interfered with trade and cheap transportation needed to alleviate local famines or shortages.[4]

Tolls were used in the Holy Roman Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries.

17th-century Dahomey

[edit]After significant road construction undertaken by the West African kingdom of Dahomey, toll booths were also established with the function of collecting yearly taxes based on the goods carried by the people of Dahomey and their occupation. In some cases, officials imposed fines for public nuisance before allowing people to pass.[5]

19th century

[edit]Industrialisation in Europe needed major improvements to the transport infrastructure which included many new or substantially improved roads, financed from tolls. The A5 road in Britain was built to provide a robust transport link between Britain and Ireland and had a toll house every few miles.

20th century

[edit]In the 20th century, road tolls were introduced in Europe to finance the construction of motorway networks and specific transport infrastructure such as bridges and tunnels.

Italy was the first country in the world to build motorways reserved for fast traffic and for motor vehicles only.[6][7] The Autostrada dei Laghi ("Lakes Motorway"), the first built in the world, connecting Milan to Lake Como and Lake Maggiore, and now parts of the Autostrada A8 and Autostrada A9, was devised by Piero Puricelli and was inaugurated in 1924.[7] Piero Puricelli, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, received the first authorization to build a public-utility fast road in 1921, and completed the construction (one lane in each direction) between 1924 and 1926. Piero Puricelli decided to cover the expenses by introducing a toll.[8]

It was followed by Greece, which made users pay for the network of motorways around and between its cities in 1927. Later in the 1950s and 1960s, France, Spain, and Portugal started to build motorways largely with the aid of concessions, allowing rapid development of this infrastructure without massive state debts. Since then, road tolls have been introduced in the majority of the EU member states.[9]

In the United States, prior to the introduction of the Interstate Highway System and the large federal grants supplied to states to build it, many states constructed their first freeways by floating bonds backed by toll revenues. The first major fully grade separated toll road was the Pennsylvania Turnpike in 1940. This was followed up by other toll roads, such as the Maine Turnpike in 1947, the Blue Star Turnpike in 1950, the New Jersey Turnpike in 1951, the Garden State Parkway in 1952, the West Virginia Turnpike and New York State Thruway in 1954, the Massachusetts Turnpike in 1957, and the Chicago Skyway and Indiana Toll Road in 1958. Other toll roads were also established around this time. With the establishment of the Interstate Highway System in the late 1950s, toll road construction in the U.S. slowed down considerably, as the federal government now provided the bulk of funding to construct new freeways, and regulations required that such Interstate highways be free from tolls. Many older toll roads were added to the Interstate System under a grandfather clause that allowed tolls to continue to be collected on toll roads that predated the system. Some of these such as the Connecticut Turnpike and the Richmond–Petersburg Turnpike later removed their tolls when the initial bonds were paid off. Many states, however, have maintained the tolling of these roads as a consistent source of revenue.

As the Interstate Highway System approached completion during the 1980s, states began constructing toll roads again to provide new freeways which were not part of the original interstate system funding. Houston's outer beltway of interconnected toll roads began in 1983, and many states followed over the last two decades of the 20th century adding new toll roads, including the tollway system around Orlando, Florida, Colorado's E-470, and Georgia State Route 400.

21st century

[edit]

London, in an effort to reduce traffic within the city, instituted the London congestion charge in 2003, effectively making all roads within the centre of the city tolled.

In the United States, as states looked for ways to construct new freeways without federal funding again, to raise revenue for continued road maintenance, and to control congestion, new toll road construction saw significant increases during the first two decades of the 21st century. Spurred on by two innovations, the electronic toll collection system, and the advent of high-occupancy and express lane tolls, many areas of the U.S. saw large road building projects in major urban areas. Electronic toll collection, first introduced in the 1980s, reduces operating costs by removing toll collectors from roads. Tolled express lanes, by which certain lanes of a freeway are designated "toll only", increases revenue by allowing a free-to-use highway to collect revenue by allowing drivers to bypass traffic jams by paying a toll.

The E-ZPass system, compatible with many state systems, is the largest ETC system in the U.S., and is used for both fully tolled highways and tolled express lanes. Maryland Route 200 and the Triangle Expressway in North Carolina were the first toll roads built without toll booths, with drivers charged via ETC or by optical license plate recognition and are billed by mail. In addition, many older toll roads are also being upgraded to an all-electronic tolling system, abandoning the hybrid systems they adopted during the late 20th century. These include the Massachusetts Turnpike, one of the oldest American toll roads, which went all-electronic in 2016, and the Pennsylvania Turnpike, America's oldest toll freeway, which went all-electronic in 2020, along with the Illinois Tollway, which both accelerated their transitions to such due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

By country

[edit]Toll roads in the United Kingdom

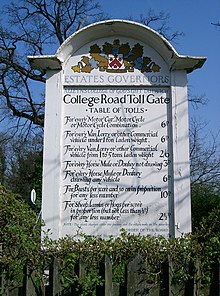

[edit]Turnpike trusts were established in England and Wales from about 1706 in response to the need for better roads than the few and poorly-maintained tracks then available. Turnpike trusts were set up by individual Acts of Parliament, with powers to collect road tolls to repay loans for building, improving, and maintaining the principal roads in Britain. At their peak, in the 1830s, over 1,000 trusts[10] administered around 30,000 miles (48,000 km) of turnpike road in England and Wales, taking tolls at almost 8,000 toll-gates.[11]

The trusts were ultimately responsible for the maintenance and improvement of most of the main roads in England and Wales, which were used to distribute agricultural and industrial goods economically. The tolls were a source of revenue for road building and maintenance, paid for by road users and not from general taxation. The turnpike trusts were gradually abolished from the 1870s. Most trusts improved existing roads, but some new roads, usually only short stretches, were also built. Thomas Telford's Holyhead road followed Watling Street from London but was exceptional in creating a largely new route beyond Shrewsbury, and especially beyond Llangollen. Built in the early 19th century, with many toll booths along its length, most of it is now the A5. In the modern day, one major toll road is the M6 Toll, relieving traffic congestion on the M6 in Birmingham. A few notable bridges and tunnels continue as toll roads including the Dartford Crossing and Mersey Gateway bridge.[citation needed]

Toll roads in Canada

[edit]Some cities in Canada had toll roads in the 19th century. Roads radiating from Toronto required users to pay at toll gates along the street (Yonge Street, Bloor Street, Davenport Road, Kingston Road)[12] but the toll gates disappeared after 1895.[13]

Toll roads in the United States

[edit]In the eastern United States of the 18th and 19th century, hundreds of private turnpikes were created to facilitate travel between towns and cities, typically outside built-up areas.

19th-century plank roads were usually operated as toll roads. One of the first US motor roads, the Long Island Motor Parkway (which opened on October 10, 1908) was built by William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt. The road was closed in 1938 when it was taken over by the state of New York in lieu of back taxes.[14][15]

Toll roads in Russia

[edit]The first toll road in St. Petersburg appeared in the 2000s. The Western High-Speed Diameter (WHSD) is a multilane motorway running from the South to the North. The road connects the southwest of the city, including the Sea Port area, with the Ring Road, Vasilievsky Island, Kurortny district and the Scandinavia motorway. The WHSD is divided into three sections: Southern, Central and Northern. The entire stretch of the WHSD was opened for traffic in 2016.

There are 16 toll plazas on the WHSD. Paying toll by transponder is mostly recommended for frequent drivers. The Flow+ toll collection system was implemented on the WHSD. The system was designed for automatic calculation of the driving distance of a vehicle equipped with a transponder. The system does not require constructing toll plazas at each entrance to or exit from the highway. Transponders mounted on vehicles are read by signal receivers installed at the entrance and exit ramps.

Toll roads in Italy

[edit]

In Italy the only toll roads are the autostrade (Italian for motorways). Major exceptions are the beltways around some larger cities (tangenziali) which are not part of a thoroughfare motorway, and the Autostrada A2 between Salerno and Reggio di Calabria which is operated by the government-owned ANAS. Both are toll free.

On Italian motorways, the toll applies to almost all motorways not managed by Anas. The collection of motorway tolls, from a tariff point of view, is managed mainly in two ways: either through the "closed motorway system" (km travelled) or through the "open motorway system" (flat-rate toll).[16]

Given the multiplicity of operators, the toll is only requested when exiting the motorway and not when the motorway operator changes. This system was made possible following article 14 of law 531 of 12 August 1982.[17]

From a technical point of view, however, the mixed barrier/free-flow system is active where, at the entrance and exit from the motorways, there are lanes dedicated to the collection of a ticket (on entry) and the delivery of the ticket with simultaneous payment (on exit) and other lanes where, during transit without the need to stop, an electronic toll system[18] present in the vehicles records the data and debits the toll, generally into the bank account previously communicated by the customer, to the manager of his device. In Italy, this occurs through the Autostrade per l'Italia interchange system.

The Autostrada A36, Autostrada A59 and Autostrada A60 are exclusively free-flow. On these motorways, those who do not have the electronic toll device on board must proceed with the payment by subsequently communicating the data to the motorway manager (by telephone, online or by going to the offices dedicated to payment).

The closed motorway system is applied to most Italian motorways.[19] It requires the driver of the vehicle to collect a special ticket at the entrance to the motorway and pay the amount due upon exit. If equipped with an electronic toll system the two procedures are completely automatic and the driver on the detection lanes located at the entrances and exits from the motorways subject to toll payment must only proceed at a maximum speed of 30 kilometres per hour (20 mph) without the need to stop.[20] The amount is directly proportional to the distance travelled by the vehicle, the coefficient of its class and a variable coefficient from motorway to motorway, called the kilometre rate.

Unlike the closed motorway system, in the open system, the road user does not pay based on the distance travelled. Motorway barriers are arranged along the route (however not at every junction), at which the user pays a fixed sum, depending only on the class of the vehicle.[19] The user can therefore travel along sections of the motorway without paying any toll as the barriers may not be present on the section travelled.

Charging methods

[edit]Road tolls were levied traditionally for a specific access (e.g. city) or for a specific infrastructure (e.g. roads, bridges). These concepts were widely used until the last century. However, the evolution in technology made it possible to implement road tolling policies based on different concepts. The different charging concepts are designed to suit different requirements regarding purpose of the charge, charging policy, the network to the charge, tariff class differentiation, et cetera:[21]

- Time-based charges and access fees: In a time-based charging regime, a road user has to pay for a given period of time in which they may use the associated infrastructure. For the practically identical access fees, the user pays for the access to a restricted zone for a period or several days.

- Motorway and other infrastructure tolling: The term tolling is used for charging a well-defined special and comparatively costly infrastructure, like a bridge, a tunnel, a mountain pass, a motorway concession, or the whole motorway network of a country. Classically a toll is due when a vehicle passes a tolling station, be it a manual barrier-controlled toll plaza or a free-flow multi-lane station.

- Distance or area charging: In a distance or area charging system concept, vehicles are charged per total distance driven in a defined area.

Some toll roads charge a toll in only one direction. Examples include the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Sydney Harbour Tunnel, and Eastern Distributor (these all charge tolls city-bound) in Australia, in the United States, crossings between Pennsylvania and New Jersey operated by Delaware River Port Authority and crossings between New Jersey and New York operated by Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. This technique is practical where the detour to avoid the toll is large or the toll differences are small.

Collection methods

[edit]

Traditionally, tolls were paid by hand at a toll gate. Although payments may still be made in cash, it is more common now to pay using an electronic toll collection system. In some places, payment is made using transponders which are affixed to the windscreen.

Three systems of toll roads exist: open (with mainline barrier toll plazas); closed (with entry/exit tolls); and open road (no toll booths, only electronic toll collection gantries at entrances and exits or at strategic locations on the median of the road). Some toll roads use a combination of the three systems.

On an open toll system, all vehicles stop at various locations along the highway to pay a toll. (This is different from "open road tolling", where no vehicles stop to pay a toll.) While this may save money from the lack of need to construct toll booths at every exit, it can cause traffic congestion while traffic queues at the mainline toll plazas (toll barriers). It is also possible for motorists to enter an 'open toll road' after one toll barrier and exit before the next one, thus travelling on the toll road toll-free. Most open toll roads have ramp tolls or partial access junctions to prevent this practice, known in the U.S. as "shunpiking".

With a closed toll system, vehicles collect a ticket when entering the highway. In some cases, the ticket displays the toll to be paid on exit. Upon exit, the driver must pay the amount listed for the given exit. Should the ticket be lost, a driver must typically pay the maximum amount possible for travel on that highway. Short toll roads with no intermediate entries or exits may have only one toll plaza at one end, with motorists travelling in either direction paying a flat fee either when they enter or when they exit the toll road. In a variant of the closed toll system, mainline barriers are present at the two endpoints of the toll road, and each interchange has a ramp toll that is paid upon exit or entry. In this case, a motorist pays a flat fee at the ramp toll and another flat fee at the end of the toll road; no ticket is necessary. In addition, with most systems, motorists may pay tolls only with cash or change; debit and credit cards are not accepted. However, some toll roads may have travel plazas with ATMs so motorists can stop and withdraw cash for the tolls.

The toll is calculated by the distance travelled on the toll road or the specific exit chosen. In the United States, for instance, the Kansas Turnpike, Ohio Turnpike, New Jersey Turnpike, most of the Indiana Toll Road, New York State Thruway, and Florida's Turnpike currently implement closed systems.

The Union Toll Plaza on the Garden State Parkway was the first ever to use an automated toll collection machine. A plaque commemorating the event includes the first quarter collected at its toll booths.[22]

The first major deployment of an RFID electronic toll collection system in the United States was on the Dallas North Tollway in 1989 by Amtech (see TollTag). The Amtech RFID technology used on the Dallas North Tollway was originally developed at Sandia Labs for use in tagging and tracking livestock. In the same year, the Telepass active transponder RFID system was introduced across Italy. Several US states now use mobile tolling platforms to facilitate use of payment via smartphones.

Highway 407 in the province of Ontario, Canada, has no toll booths, and instead reads a transponder mounted on the windshields of each vehicle using the road (the rear licence plates of vehicles lacking a transponder are photographed when they enter and exit the highway). This made the highway the first all-automated toll highway in the world. A bill is mailed monthly for usage of the 407. Lower charges are levied on frequent 407 users who carry electronic transponders in their vehicles. The approach has not been without controversy: In 2003 the 407 ETR settled[23] a class action with a refund to users.

Throughout most of the East Coast of the United States, E-ZPass (operated under the brand I-Pass in Illinois) is accepted on almost all toll roads. Similar systems include SunPass in Florida, FasTrak in California, Good to Go in Washington state, and ExpressToll in Colorado. The systems use a small radio transponder mounted in or on a customer's vehicle to deduct toll fares from a pre-paid account as the vehicle passes through the toll barrier. This reduces manpower at toll booths and increases traffic flow and fuel efficiency by reducing the need for complete stops to pay tolls at these locations.

By designing a toll gate specifically for electronic collection, it is possible to carry out open-road tolling, where the customer does not need to slow at all when passing through the toll gate. The U.S. state of Texas is using a system that has no toll booths. Drivers without a TollTag have their license plate photographed automatically and the registered owner will receive a monthly bill, at a higher rate than those vehicles with TollTags. A similar variation of automatic collection is the Toll Roads in Orange County, CA, US, wherein all entry or collection points are equipped with high-speed cameras which read license plates and users will have 7 calendar days to pay online using their plate number or else set up an account for automatic debits.

The first all-electronic toll road in the northeastern United States, the InterCounty Connector (Maryland Route 200) was partially opened to traffic in February 2011,[24] and the final segment was completed in November 2014.[25] The first section of another all-electronic toll road, the Triangle Expressway, opened at the beginning of 2012 in North Carolina.[26]

Financing and management

[edit]Some toll roads are managed under such systems as the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) system. Private companies build the roads and are given a limited franchise. Ownership is transferred to the government when the franchise expires. This type of arrangement is prevalent in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Indonesia, India, South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines. The BOT system is a fairly new concept that is becoming more popular in the United States, with California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Mississippi,[27] Texas, and Virginia already building and operating toll roads under this scheme. Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Tennessee are also considering the BOT methodology for future highway projects.

The more traditional means of managing toll roads in the United States is through semi-autonomous public authorities. Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia manage their toll roads in this manner. While most of the toll roads in California, Delaware, Florida, Texas, and Virginia are operating under the BOT arrangement, a few of the older toll roads in these states are still operated by public authorities.

In France, some toll roads are operated by private or public companies, with specific taxes collected by the state.[citation needed]

Arguments against toll roads

[edit]Toll roads have been criticised[by whom?] as being inefficient in various ways:[28]

- They require vehicles to stop or slow down (except open road tolling); manual toll collection wastes time and raises vehicle operating costs.[citation needed]

- Collection costs can reduce revenue by up to a third, and revenue theft is considered[by whom?] to be comparatively easy.[citation needed]

- Where the tolled roads are less congested than the parallel "free" roads, the traffic diversion resulting from the tolls increases congestion on the road system and reduces its usefulness.[29]

- There are concerns about government surveillance associated with both electronic tolls and some forms of "classical" toll collection.

A number of additional criticisms are also directed at toll roads in general:

- Toll roads are a form of regressive taxation; that is, compared to conventional taxes for funding roads, they benefit wealthier citizens more than poor citizens.[30][31]

- If toll roads are owned or managed by private for profit entities, the citizens may lose money overall compared to conventional public funding because the private owners or operators of the toll system will naturally seek to profit from the roads.[32]

- The managing entities, whether public or private, may not correctly account for the overall social costs, particularly to the poor, when setting pricing and thus may hurt the neediest segments of society.[33]

Arguments in favor of toll roads

[edit]- Tolls help internalize some of the externalities of automobiles, that is costs automobile traffic imposes on society that are not borne by users.[34][35]

- Through dynamic pricing trips that do not have to occur at rush hour can be moved to other times of the day or be avoided altogether. This makes more efficient use of existing road capacity.[36][37]

Gallery

[edit]-

Tipo toll plaza in Subic–Clark–Tarlac Expressway, Hermosa, Bataan, Philippines, before the integration with NLEX.

-

The open road tolling lanes at the West 163rd Street toll plaza, on the Tri-State Tollway near Markham, Illinois, United States

-

In 2018 Rhode Island became one of the first states to set up gantries to exclusively toll only tractor trailer trucks. Gantry shown on I-95 North.

See also

[edit]- List of toll roads

- Geography of toll roads

- Automobile costs

- Barrier toll system

- High-occupancy toll lane

- Private highway

- Shadow toll

- Shunpiking, the practice of avoiding turnpikes

- Toll house

- Turnpike trusts – England and Wales

- Freeway

References

[edit]- ^ "Road Pricing Defined". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Gilliet, Henri (1990). "Toll roads-the French experience." Transrouts International, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines.

- ^ "Toll". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, William J.; "The Birth of Plenty: How the Prosperity of the Modern World was Created"; p. 245-6; McGraw-Hill (2010); ISBN 978-0071747042

- ^ Herskovits, Melville J. (1967). Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom (Volume I ed.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ a b Lenarduzzi, Thea (30 January 2016). "The motorway that built Italy: Piero Puricelli's masterpiece". The Independent. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "The "Milano-Laghi" by Piero Puricelli, the first motorway in the world". Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "1924 Mile Posts". Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2006.

- ^ Jordi, Philipp (2008): "Institutional Aspects of Directive 2004/52/EC on the Interoperability of Electronic Road Toll Systems in the Community." Europainstitut der Universität Basel.

- ^ Parliamentary Papers, 1840, Vol 280 xxvii.

- ^ Searle, M. (1930). Turnpikes and Toll Bars (Limited ed.). Hutchinson & Co. p. 798.

- ^ "Toronto.ca". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ "Lostrivers.ca". Archived from the original on May 19, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ Patton, Phil (October 12, 2008). "A 100-Year-Old Dream: A Road Just for Cars". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "BBS.keyhole.com". Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ "Come si calcola il pedaggio - Autostrade per l'Italia S.p.A" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Legge 12 agosto 1982, n. 531. - Piano decennale per la viabilità di grande comunicazione e misure di riassetto del settore autostradale" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ In Italy the devices allowed are Telepass, MooneyGo, UnipolMove and other devices pursuant to EU regulations

- ^ a b "Dove sono i pedaggi?" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ "PER VIAGGIARE IN ITALIA TELEPASS E VIACARD" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Oehry, Bernhard (2004): Tolling with Satellites – a System Concept for Everybody?" in: Jordi, Philipp (2008): "Institutional Aspects of Directive 2004/52/EC on the Interoperability of Electronic Road Toll Systems in the Community." Europainstitut der Universität Basel.

- ^ "Union Watersphere". lostinjersey.wordpress.com. March 19, 2009. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ "407ETR.com" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2010.

- ^ Michael Dresser (February 7, 2011). "First phase of ICC to open Feb. 22". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on February 10, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ Kevin Rector (November 5, 2014). "Final section of ICC to Laurel, new I-95 interchange to open this weekend". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ "Drivers roll on state's first toll road". WRAL.com. January 31, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2012.

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ Roth, Gabriel (1998). Roads in a market economy. Ashgate Publishing Company. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-291-39814-7.

- ^ Chronicle (2013-04-07). "Eliminate toll roads". Chronicle Online. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Peters, Jonathan R.; Kramer, Jonathan K. (Summer 2003). "The Inefficiency of Toll Collection as a Means of Taxation: Evidence from the Garden State Parkway" (PDF). Transportation Quarterly. 57: 26.

Nakamura and Kockelman (2002) show that tolls are by nature regressive ...

- ^ Robertson, Christopher Charles; Prozzi, Jolanda; Walton, C. Michael (2008). Who Uses Toll Roads?: An Analysis of Central Texas Turnpike Users. Southwest Regional University Transportation Center, Center for Transportation Research, University of Texas at Austin. p. 30. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018.

Low income users unable to pay to use toll facilities, however, will not gain most of the benefits accessible to those with the ability to pay. ... The study concludes that ... toll roads are a regressive form of funding road systems ...

- ^ Kurtz, David L.; Boone, Louis E. (2008). Contemporary Business. South-Western Cengage Learning. p. 17. ISBN 978-0324653847. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ von Hirschhausen, Christian (January 1, 2002). Modernizing Infrastructure in Transformation Economies. Edward Elgar. p. 155. ISBN 9781781959787. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Toll Roads and Externalities". 18 August 2004.

- ^ Yin, Yafeng; Lawphongpanich, Siriphong (1 July 2006). "Internalizing emission externality on road networks". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 11 (4): 292–301. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2006.05.003.

- ^ "Dynamic Pricing on the Road: How Managed Tolls Are Increasing Efficiency and Innovation". 16 November 2015.

- ^ Liu, Louie Nan; McDonald, John F. (1 November 1998). "Efficient Congestion Tolls in the Presence of Unpriced Congestion: A Peak and Off-Peak Simulation Model". Journal of Urban Economics. 44 (3): 352–366. doi:10.1006/juec.1997.2073.

External links

[edit]- Turnpike Info

- Toll Tickets Official Website

- International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association The International Bridge, Tunnel and Turnpike Association (IBTTA) is the worldwide alliance of toll operators and associated industries that provides a forum for sharing knowledge and ideas to promote and enhance toll-financed transportation services.

- Toll Roads News from contractor perspective

- Turnpike Roads in England and Wales, for background on toll roads during the turnpike era in England