Tom Coburn

Tom Coburn | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2005 | |

| United States Senator from Oklahoma | |

| In office January 3, 2005 – January 3, 2015 | |

| Preceded by | Don Nickles |

| Succeeded by | James Lankford |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Oklahoma's 2nd district | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Mike Synar |

| Succeeded by | Brad Carson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Allen Coburn March 14, 1948 Casper, Wyoming, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 2020 (aged 72) Tulsa, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Carolyn Denton (m. 1968) |

| Children | 3, including Sarah |

| Education | Oklahoma State University–Stillwater (BS) University of Oklahoma (MD) |

Thomas Allen Coburn (March 14, 1948 – March 28, 2020) was an American politician and physician who served as a United States senator from Oklahoma from 2005 to 2015. A Republican, Coburn previously served as a United States representative from 1995 to 2001.

Coburn was an obstetrician who operated a private medical practice in Muskogee, Oklahoma. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1994 as part of the Republican Revolution. After being re-elected twice, Coburn upheld his campaign pledge to serve no more than three consecutive terms and did not seek re-election in 2000. In 2004, he returned to political life with a successful run for the United States Senate. Coburn was re-elected to a second Senate term in 2010 and kept his pledge not to seek a third term in 2016.[1] In January 2014, Coburn announced that he would resign before the expiration of his final term due to a recurrence of prostate cancer.[2] He submitted a letter of resignation to Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, effective at the end of the 113th Congress.[3]

Coburn was a fiscal and social conservative known for his opposition to deficit spending, pork barrel projects,[4][5][6] and abortion. Described as "the godfather of the modern conservative austerity movement",[7] he supported term limits, gun rights and the death penalty,[8] and opposed same-sex marriage and embryonic stem cell research.[9][10] Many Democrats referred to him as "Dr. No" due to his frequent use of technicalities to block federal spending bills.[11][12]

After leaving Congress, Coburn worked with the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research on its efforts to reform the Food and Drug Administration,[13] becoming a senior fellow of the institute in December 2016.[14] Coburn also served as a senior advisor to Citizens for Self-Governance, where he was active in calling for a convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution.[15][16][17]

Early life, education, and medical career

[edit]Coburn was born in Casper, Wyoming, the son of Anita Joy (née Allen) and Orin Wesley Coburn.[18] Coburn's father was an optician and founder of Coburn Optical Industries, and a named donor to O. W. Coburn School of Law at Oral Roberts University.[19]

Coburn graduated with a B.S. in accounting from Oklahoma State University,[20] where he was also a member of Sigma Nu fraternity. In 1968, he married Carolyn Denton,[20] the 1967 Miss Oklahoma;[21] their three daughters are Callie,[22] Katie and Sarah, a leading operatic soprano.[23] One of the top ten seniors in the School of Business, Coburn served as president of the College of Business Student Council.[24]

From 1970 to 1978, Coburn served as a manufacturing manager at the Ophthalmic Division of Coburn Optical Industries in Colonial Heights, Virginia. While Coburn was manager, the Virginia division of Coburn Optical grew from 13 employees to over 350 and captured 35 percent of the U.S. market.[24]

After recovering from an occurrence of malignant melanoma, Coburn pursued a medical degree and graduated from the University of Oklahoma Medical School with honors in 1983.[20] He then opened Maternal & Family Practice in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and served as a deacon in a Southern Baptist Church. During his career in obstetrics, he treated over 15,000 patients, delivered 4,000 babies and was subject to one malpractice lawsuit, which was dismissed without finding Coburn at fault.[25][26] Together Coburn and his wife were members of First Baptist Church of Muskogee.[27]

Sterilization controversy

[edit]A sterilization Coburn performed on a 20-year-old woman, Angela Plummer, in 1990, became what was called "the most incendiary issue" of his Senate campaign.[28] Coburn performed the sterilization on the woman during an emergency surgery to treat a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy, removing her healthy intact fallopian tube as well as the one damaged by the surgery. The woman sued Coburn, alleging that he did not have consent to sterilize her, while Coburn claimed he had her oral consent. The lawsuit was ultimately dismissed with no finding of liability on Coburn's part.[29]

The state attorney general claimed that Coburn committed Medicaid fraud by not reporting the sterilization when he filed a claim for the emergency surgery. Medicaid did not reimburse doctors for sterilization procedures for patients under 21 and according to the attorney general, Coburn would not have been reimbursed at all had he disclosed this information. Coburn says since he did not file a claim for the sterilization, no fraud was committed. No charges were filed against Coburn for this claim.[10][26][30][31]

Political career

[edit]House career

[edit]In 1994, Coburn ran for the House of Representatives in Oklahoma's 2nd congressional district, which was based in Muskogee and included 22 counties in northeastern Oklahoma. Coburn initially expected to face eight-term incumbent Mike Synar. However, Synar was defeated in a runoff for the Democratic nomination by a 71-year-old retired principal, Virgil Cooper. According to Coburn's 2003 book, Breach of Trust: How Washington Turns Outsiders Into Insiders, Coburn and Cooper got along well, since both were opposed to the more liberal Synar. The general election was cordial since both men knew that Synar would not return to Washington regardless of the outcome. Coburn won by a 52%–48% margin, becoming the first Republican to represent the district since 1921.[32]

Coburn was one of the most conservative members of the House. He supported "reducing the size of the federal budget," wanted to make abortion illegal and supported the proposed television V-chip legislation.[33]

Despite representing a heavily Democratic district and President Bill Clinton's electoral dominance therein, Coburn was reelected in 1996 and 1998.[34][35]

In the House, Coburn earned a reputation as a political maverick due to his frequent battles with House Speaker Newt Gingrich.[36] Most of these stand-offs stemmed from his belief that the Republican caucus was moving toward the political center and away from the more conservative Contract With America policy proposals that had brought the Republicans into power in Congress in 1994 for the first time in 40 years.[37]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Coburn endorsed conservative activist and former diplomat Alan Keyes in the 2000 Republican presidential primaries.[38] Coburn retired from Congress in 2001, fulfilling his pledge to serve no more than three terms in the House. His congressional district returned to the Democratic fold, as attorney Brad Carson defeated Andy Ewing, a Republican endorsed by Coburn. After leaving the House and returning to private medical practice, Coburn wrote Breach of Trust, with ghostwriter John Hart, about his experiences in Congress. The book detailed Coburn's perspective on the internal Republican Party debates over the Contract With America and displayed his disdain for career politicians. Some of the figures he criticized (such as Gingrich) were already out of office at the time of the book's publishing, but others (such as former House Speaker Dennis Hastert) remained influential in Congress, which resulted in speculation that some congressional Republicans wanted no part of Coburn's return to politics.[39]

During his tenure in the House, Coburn wrote and passed far-reaching pieces of legislation. These include laws to expand seniors' health care options, to protect access to home health care in rural areas and to allow Americans to access cheaper medications from Canada and other nations. Coburn also wrote a law intended to prevent the spread of AIDS to infants. The Wall Street Journal said about the law, "In 10 long years of AIDS politics and funding, this is actually the first legislation to pass in this country that will rescue babies." He also wrote a law to renew and reform federal AIDS care programs.[12] In 2002, President George W. Bush chose Coburn to serve as co-chair of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS (PACHA).[40]

During his three terms in the House, Coburn also played an influential role in reforming welfare and other federal entitlement programs.[12]

Schindler's List TV broadcast

[edit]As a congressman in 1997, Coburn protested NBC's plan to air the R-rated Academy Award-winning Holocaust drama Schindler's List during prime time.[41] Coburn stated that, in airing the movie without editing it for television, TV had been taken "to an all-time low, with full-frontal nudity, violence and profanity."[42][43] He also said the TV broadcast should outrage parents and decent-minded individuals everywhere. Coburn described the airing of Schindler's List on television as "irresponsible sexual behavior. I cringe when I realize that there were children all across this nation watching this program."[44]

This statement met with strong criticism, as the film deals mainly with the Holocaust.[45] After heavy criticism, Coburn apologized "to all those I have offended" and clarified that he agreed with the movie being aired on television, but stated that it should have been on later in the evening. In apologizing, Coburn said that at that time of the evening there are still large numbers of children watching without parental supervision and stated that he stood by his message of protecting children from violence, but had expressed it poorly. He also said, "My intentions were good, but I've obviously made an error in judgment in how I've gone about saying what I wanted to say."[46][47][48]

He later wrote in Breach of Trust that he considered this one of the biggest mistakes in his life and that, while he still felt the material was unsuitable for a 7 p.m. television broadcast, he handled the situation poorly.[49]

Senate career

[edit]After three years out of politics, Coburn announced his candidacy for the Senate seat being vacated by four-term incumbent Republican Don Nickles. Former Oklahoma City Mayor Kirk Humphreys (the favorite of the state and national Republican establishment) and Corporation Commissioner Bob Anthony joined the field before Coburn. However, Coburn won the primary by an unexpectedly large margin, taking 61% of the vote to Humphreys's 25%. In the general election, he faced Brad Carson, the Democrat who had succeeded him in the 2nd District and was giving up his seat after only two terms.[50]

In the election, Coburn won by a margin of 53% to Carson's 42%. While Carson routed Coburn in the generally heavily Democratic 2nd District, Coburn swamped Carson in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area and the closer-in Tulsa suburbs. Coburn won the state's two largest counties, Tulsa and Oklahoma, by a combined 86,000 votes, more than half of his overall margin of 166,000 votes cast.[51]

Coburn's Senate voting record was as conservative as his House record.[11]

Coburn was re-elected in 2010. He received 90% of the vote in the Republican primary and 70% in the general election. While he already planned on not seeking a third term in the Senate due to his self-imposed two-term term limit, on January 16, 2014, Coburn announced he would resign his office before his term ended at the end of the year due to his declining health.[52]

On April 29, 2014, Coburn introduced the Insurance Capital Standards Clarification Act of 2014 (S. 2270; 113th Congress) into the Senate and it passed on June 3, 2014.[53]

Use of Senate hold

[edit]Coburn used the Senate hold privilege to prevent several bills from coming to the Senate floor.[54] Coburn earned a reputation for his use of this procedural mechanism.[54] In November 2009 Coburn drew attention for placing a hold on a veterans benefits bill known as the Veterans' Caregiver and Omnibus Health Benefits Act.[55][56] Coburn also placed a hold on a bill intended to help end hostilities in Uganda by the Lord's Resistance Army.[57]

On May 23, 2007, Coburn blocked two bills honoring the 100th birthday of Rachel Carson. Coburn called Carson's scientific work "junk science," proclaiming that Carson's landmark book Silent Spring was "the catalyst in the deadly worldwide stigmatization against insecticides, especially DDT."[58] Democratic Senator Benjamin L. Cardin of Maryland had intended to submit a resolution celebrating Carson for her "legacy of scientific rigor coupled with poetic sensibility,"[59] but Coburn blocked it, saying that "the junk science and stigma surrounding DDT—the cheapest and most effective insecticide on the planet—have finally been jettisoned."[60]

In response to Coburn's holds, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid introduced the Advancing America's Priorities Act, S. 3297, in July 2008. S. 3297 combined thirty-five bills which Coburn had blocked into what Democrats called the "Tomnibus" bill.[11][61] The bill included health care provisions, new penalties for child pornography, and several natural resources bills.[62] The bill failed a cloture vote.[63]

Coburn opposed parts of the legislation creating the Lewis and Clark Mount Hood Wilderness Area, which would add protections to wildlands in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.[64] Coburn exercised a hold on the legislation in both March and November 2008,[65][66] and decried the required $10 million for surveying and mapping as wasteful.[67] The Mount Hood bill would have been the largest amount of land added to federal protection since 1984.[67]

In March 2009, those wilderness areas became protected under the Omnibus Public Land Management Act, which passed the Senate 73–21.[68]

According to the Boston Globe, Coburn initially blocked passage of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), objecting to provisions in the bill that allow discrimination based on genetic information from embryos and fetuses. After the embryo loophole was closed, Coburn lifted his hold on the bill.[69]

Coburn had initially blocked passage of the LRA Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act, which would help to disarm the Lord's Resistance Army, a political group accused of human rights abuses. On March 9, 2010, Coburn lifted his hold on the LRA bill freeing it to move to the Senate floor after reaching a compromise regarding the funding of the bill,[70] and an eleven-day protest outside of his office.[71]

John Ensign scandal

[edit]Coburn was affiliated with a religious organization called The Family. Coburn previously lived in one of the Family's Washington, D.C. dormitories with then-Senator John Ensign, another Family member and longtime resident of the C Street Center who admitted he had an extramarital affair with a staffer in 2009. The announcement by Ensign of his infidelity brought public scrutiny of the Family and its connection to other high-ranking politicians, including Coburn.[72]

Coburn, together with senior members of the Family, attempted to intervene to end Ensign's affair in February 2008, before the affair became public, including by meeting with the husband of Ensign's mistress and encouraging Ensign to write a letter to his mistress breaking off the affair.[73][74][75] Ensign was driven to a branch of Federal Express from the C Street Center to post the letter, shortly after which Ensign called to tell his mistress to ignore it.[73][74][75]

Coburn refused to speak about his involvement in Ensign's affair or his knowledge of the affair well before it became public, asserting legal privilege due to his statuses as a licensed physician in Oklahoma and a deacon.[76]

In October 2009, Coburn made a statement to The New York Times about Ensign's affair and cover-up: "John got trapped doing something really stupid and then made a lot of other mistakes afterward. Judgment gets impaired by arrogance and that's what's going on here."[77]

In May 2011, the Senate Ethics Committee identified Coburn in their report on the ethics violations of Ensign. The report stated that Coburn knew about Ensign's extramarital affair and was involved in trying to negotiate a financial settlement to cover it up.[78]

Whistleblower rights

[edit]Coburn was involved in the Bush Administration's struggle with Congress over whistleblower rights. In the case of Garcetti v. Ceballos, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that government employees who testify against their employers did not have protection from retaliation by their employers under the First Amendment of the Constitution.[79] The free speech protections of the First Amendment have long been used to shield whistleblowers from retaliation.[80]

In response to the Supreme Court decision, the House passed H.R. 985, the Whistleblower Protection Act of 2007. Bush, citing national security concerns, promised to veto the bill should it be passed by Congress. The Senate's version of the Whistleblower Protection Act (S. 274) was approved by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs on June 13, 2007. However, that version failed to reach a vote by the Senate, as Coburn placed a hold on the bill; effectively preventing the passage of the bill, which had bipartisan support in the Senate.[81]

Coburn's website features a news item about United Nations whistleblower Mathieu Credo Koumoin, a former employee for the U.N. Development Program in West Africa, who has asked U.N. ethics chief Robert Benson for protection under the U.N.'s whistleblower protection rules.[82] The site has a link to the "United Nations Watch" of the Republican Office of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs' Subcommittee on Federal Financial Management, Government Information and International Security, of which he was the ranking minority member.[83] Coburn's website also features a tip line for potential whistleblowers on government waste and fraud.[84]

Council on American–Islamic Relations

[edit]Coburn joined Congressmen Sue Myrick (R-NC), Trent Franks (R-AZ), John Shadegg (R-AZ), Paul Broun (R-GA) and Patrick McHenry (R-NC) in a letter to IRS Commissioner Douglas H. Shulman on November 16, 2009, asking that the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) be investigated for excessive lobbying and failing to register as a lobbying organization.[85] The request came in the wake of the publication of a book, Muslim Mafia, the foreword of which had been penned by Myrick, that portrayed CAIR as a subversive organization allied with international terrorists.[86]

Criticism of the National Science Foundation

[edit]On May 26, 2011, Coburn released a 73-page report, "National Science Foundation: Under the Microscope",[87][88] receiving attention from The New York Times, Fox News and MSNBC.[89][90][91]

STOCK Act

[edit]Coburn was one of three senators who voted against the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act (STOCK Act).[92] On February 3, 2012, Coburn released the following statement regarding the Act:

It's disappointing the Senate spent a week debating a bill that duplicates existing law and fails to address the real problems facing the country. The only way we can restore confidence in Congress is to make hard choices and solve real problems by doing things like reforming our tax code, repairing our safety net and reducing our crushing debt burden. Doing anything less will further alienate the American people and rightfully so.[93]

Committee assignments

[edit]Coburn was a member of the following committees:

- Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs (Ranking Member)

- Select Committee on Intelligence

- Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

Political positions

[edit]Abortion

[edit]Coburn opposed abortion, with the exception of abortions necessary to save the life of the mother. In 2000, he sponsored a bill to prevent the Food and Drug Administration from developing, testing, or approving the abortifacient RU-486. On July 13, the bill failed in the House of Representatives by a vote of 182 to 187.[94] On the issue, Coburn sparked controversy with his remark, "I favor the death penalty for abortionists and other people who take life."[8][95] He noted that his great-grandmother was raped by a sheriff.[96]

Coburn was one of the original authors of the federal Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act upheld by the United States Supreme Court in Gonzales v. Carhart.[97] The act relied on an expansive view of the Constitution's Commerce Clause, as it applies to "any physician who, in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce, knowingly performs a partial-birth abortion."[97] The Act's reliance on such a broad reading of the Commerce Clause was criticized by Independence Institute scholar David Kopel and University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds, who noted that "[u]nless a physician is operating a mobile abortion clinic on the Metroliner, it is not really possible to perform an abortion 'in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce.'"[98] When Coburn later called Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan "ignorant" due to her "very expansive view" of the Commerce Clause, his support for the Act was used by Kagan supporters who charged him with hypocrisy on the issue.[97]

On September 14, 2005, during the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee John Roberts, Coburn began his opening statement with a critique of Beltway partisan politics while, according to news reports, "choking back a sob."[99] Coburn had earlier been completing a crossword puzzle during the hearings,[99] and this fact was highlighted by The Daily Show with Jon Stewart to ridicule Coburn's pathos.[100] Coburn then began his questioning by discussing the various legal terms mentioned during the previous day's hearings. Proceeding to questions regarding both abortion and end-of-life issues, Coburn, who noted that during his tenure as an obstetrician he had delivered some 4,000 babies, asked Roberts whether the judge agreed with the proposition that "the opposite of being dead is being alive."

You know I'm going somewhere. One of the problems I have is coming up with just the common sense and logic that if brain wave and heartbeat signifies life, the absence of them signifies death, then the presence of them certainly signifies life. And to say it otherwise, logically is schizophrenic. And that's how I view a lot of the decisions that have come from the Supreme Court on the issue of abortion.[101]

Climate change

[edit]Coburn was a climate change denier, saying in 2013: "I am a global warming denier, and I don't deny that". He had previously described climate science as "crap". In 2011, Coburn introduced a bill with Democratic Maryland Senator Ben Cardin, to end the ethanol blenders' tax credit—a subsidy designed to encourage oil companies to blend more environmentally friendly ethanol into the fuels they sold to drivers.[102] Coburn asserted that climate change was a natural phenomenon, and that it was leading to a "mini-ice age".[103]

Fiscal conservatism

[edit]

The best-known of Coburn's amendments was an amendment to the fiscal 2006 appropriations bill that funds transportation projects.[104] Coburn's amendment would have transferred funding from the Bridge to Nowhere in Alaska to rebuild Louisiana's "Twin Spans" bridge, which was devastated by Hurricane Katrina. The amendment was defeated in the Senate, 82–14, after Ted Stevens, the senior senator from Alaska, threatened to resign his office if the amendment were passed. Coburn's actions did result in getting the funds made into a more politically feasible block grant to the State of Alaska, which could use the funds for the bridge or other projects. The renovations for the Elizabethtown Amtrak Station were cited by Coburn as an example of pork barrel spending in the stimulus bill.[105]

Coburn was also a member of the Fiscal Watch Team, a group of seven senators led by John McCain, whose stated goal was to combat "wasteful government spending."[106][107]

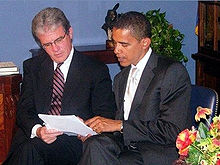

On April 6, 2006, Coburn and Senators Barack Obama, Thomas Carper and John McCain introduced the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006.[108] The bill requires the full disclosure of all entities and organizations receiving federal funds beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2007 on a website maintained by the Office of Management and Budget. The bill was signed into law on September 26, 2006.[109]

Coburn and McCain noted that the practice of members of Congress adding earmarks had risen dramatically over the years, from 121 earmarks in 1987 to 15,268 earmarks in 2005, according to the Congressional Research Service.[110]

In July 2007, Coburn criticized pork-barrel spending that Nebraska Senator Ben Nelson had inserted into the 2007 defense spending bill. Coburn said that the earmarks would benefit Nelson's son Patrick's employer with millions in federal dollars and that the situation violated terms of the Transparency Act, which was passed by the Senate but had not yet been voted on in the House. Nelson's spokesperson said the Senator did nothing wrong.[111] At that time, newspapers in Nebraska and Oklahoma noted that Coburn failed to criticize very similar earmarks that had benefited Oklahoma.[112]

In 1997, Coburn introduced a bill called the HIV Prevention Act of 1997, which would have amended the Social Security Act. The bill would have required confidential notification of HIV exposure to the sexual partners of those diagnosed with HIV, along with counseling and testing.[113]

In 2010, Coburn called for a freeze on defense spending.[114] Coburn served on the Simpson-Bowles debt reduction commission in 2010 and was one of the only Republicans in Congress open to tax increases as a means of balancing the budget.[115]

In 2011 Coburn broke with Americans for Tax Reform with an ethanol amendment that gathered 70 votes in the Senate. He said that anti-tax activist Grover Norquist's influence was overstated, and that revenue increases were needed in order to "fix the country."[116][117]

In 2012, Coburn identified less than $7 billion a year in possible defense savings and over half of these savings were to be through the elimination of military personnel involved in supply, transportation, and communications services.[118]

In May 2013, after tornadoes ripped through his state, Coburn said that any new funding allocated for disaster relief needed to be offset by cuts to other federal spending.[119]

Coburn was a fierce critic of the plan to attempt to defund the Affordable Care Act by shutting down the federal government, saying that the strategy was "doomed to fail" and that Ted Cruz and others who supported the plan had a "short-term goal with lousy tactics".[7]

Gun rights

[edit]In regards to the Second Amendment, Coburn believed that it "recognizes the right of individual, law-abiding citizens to own and use firearms," and he opposed "any and all efforts to mandate gun control on law-abiding citizens."[120] On the Credit CARD Act of 2009, which aimed "to establish fair and transparent practices relating to the extension of credit under an open-end consumer credit plan and for other purposes,"[121] Coburn sponsored an amendment that would allow concealed carry of firearms in national parks. The Senate passed the amendment 67–29.[122]

Coburn placed a hold on final Senate consideration of a measure passed by the House in the wake of the Virginia Tech shootings to improve state performance in checking the federal watch list of gun buyers.[123] However, after the Sandy Hook massacre in December 2012, Coburn (who had already announced he would not run for re-election) reversed himself and came out in support of universal background checks.[124] Coburn partnered with Democratic members of the Senate such as Charles Schumer and Joe Manchin (to whose re-election campaign Coburn donated money[125]) to determine what a universal background check measure should look like. However, these talks ultimately broke down, and in April 2013, Coburn was one of 46 senators to vote against the amendment in its final form, defeating its passage.[126][127]

Health care reform

[edit]

Coburn voted against the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in December 2009,[128] and against the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010.[129]

Coburn co-authored the Patients Choice Act of 2009[130] (S. 1099), a Republican plan for health care reform in the United States,[131] which required the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to convene an interagency coordinating committee to develop a national strategic plan for prevention in its first section, and provided for health promotion and disease prevention activities consistent with such a plan, while seeking to terminate the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[132] The act set forth provisions governing the establishment and operation of state-based health care exchanges to facilitate the individual purchase of private health insurance, and the creation of a market where private health plans compete for enrollees based on price and quality; it intended to amend the Internal Revenue Code to allow a refundable tax credit for qualified health care insurance coverage. The act also set forth programs to prevent Medicare fraud and abuse, including ending the use of social security numbers to identify Medicare beneficiaries.

Presidential nominations to the Judicial and Executive branches of government

[edit]During the administration of President George W. Bush, Coburn spoke out against the threat by some Democrats to filibuster nominations to judicial and Executive Branch positions. He took the position that no presidential nomination should ever be filibustered, in light of the wording of the U.S. Constitution. Coburn said, "There is a defined charge to the president and the Senate on advice and consent."[133]

In May 2009, Coburn was the only Senator to vote against the confirmation of Gil Kerlikowske as the Director of the National Drug Control Policy.[134]

Same-sex marriage

[edit]Coburn opposed same-sex marriage. In 2006, he voted in support of a proposed constitutional amendment to ban it.[135]

War in Iraq

[edit]On May 24, 2007, the U.S. Senate voted 80–14 to fund the war in Iraq, which included U.S. Troop Readiness, Veterans' Care, Katrina Recovery, and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act, 2007. Coburn voted nay.[136] On October 1, 2007, the Senate voted 92–3 to fund the war in Iraq. Coburn voted nay.[137] In February 2008, Coburn said, "I will tell you personally that I think it was probably a mistake going to Iraq."[138]

On December 15, 2014, Coburn stalled the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act aimed at stemming veteran suicides. The bill would require a report on successful veteran suicide prevention programs and allow the United States Veterans Administration to pay incentives to hire psychiatrists. Paul Rieckhoff, CEO of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, said that despite his reputation as a budget hawk, Coburn should have recognized that the $22 million cost of the bill is worth the lives it would have saved. "It's a shame that after two decades of service in Washington, Sen. Coburn will always be remembered for this final, misguided attack on veterans nationwide," he said. "If it takes 90 days for the new Congress to re-pass this bill, the statistics tell us another 1,980 vets will have died by suicide. That should be a heavy burden on the conscience of Sen. Coburn and this Congress." Speaking out against the legislation, Coburn said "I object, not because I don't want to save suicides, but because I don't think this bill will do the first thing to change what's happening," arguing that the bill "throws money and doesn't solve the real problem".[139]

Post-Senate career

[edit]After resigning from the Senate, Coburn joined Citizens for Self-Governance as a senior advisor to the group's Convention of States project, which seeks to convene a convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution.[140][141] In 2017, he authored a book on the subject titled Smashing the DC Monopoly: Using Article V to Restore Freedom and Stop Runaway Government.[142]

Coburn was affiliated with the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, consulting on the institute's Project FDA, an effort to promote faster drug approval processes.[13] He also sat on the board of the Benjamin Rush Institute, a conservative association of medical students across 20 medical schools.[143] In 2016, he became a Manhattan Institute senior fellow.[14]

Awards

[edit]In 2013, Coburn received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by the Jefferson Awards.[144]

Personal life

[edit]Despite their stark ideological differences, Coburn was a close friend of President Barack Obama. Their friendship began in 2005 when they both arrived in the Senate at the same time.[145] They worked together on political ethics reform legislation,[146] to set up an online federal spending database and to crack down on no-bid contracting at the Federal Emergency Management Agency in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. In April 2011, Coburn spoke to Bloomberg TV about Obama, saying, "I love the man. I think he's a neat man. I don't want him to be president, but I still love him. He is our President. He's my President. And I disagree with him adamantly on 95% of the issues, but that doesn't mean I can't have a great relationship. And that's a model people ought to follow."[147]

Before the 2009 BCS game between the Oklahoma Sooners and the Florida Gators, Coburn made a bet over the outcome of the game with Florida Senator Bill Nelson—the loser had to serenade the winner with a song. The Gators defeated the Sooners and Coburn sang Elton John's "Rocket Man" to Nelson, who had once flown into space.[148]

Illness and death

[edit]In November 2013, Coburn made public that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. In 2011, he had prostate cancer surgery while also surviving colon cancer and melanoma. His illness led him to resign from the Senate in 2015.[149][150][151]

Coburn died at his home in Tulsa on March 28, 2020, two weeks after his 72nd birthday.[37][152] A memorial service to honor his life was held a year later on May 1, 2021, at South Tulsa Baptist Church.[153]

Electoral history

[edit]| Year | Democratic | Votes | Pct | Republican | Votes | Pct | 3rd party | Party | Votes | Pct | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Virgil R. Cooper | 75,943 | 48% | Tom Coburn | 82,479 | 52% | |||||||

| 1996 | Glen D. Johnson | 90,120 | 45% | Tom Coburn (incumbent) | 112,273 | 55% | |||||||

| 1998 | Kent Pharaoh | 59,042 | 40% | Tom Coburn (incumbent) | 85,581 | 58% | Albert Jones | Independent | 3,641 | 2% |

| Year | Democratic | Votes | Pct | Republican | Votes | Pct | 3rd party | Party | Votes | Pct | 3rd party | Party | Votes | Pct | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Brad Carson | 596,750 | 41% | Tom Coburn | 763,433 | 53% | Sheila Bilyeu | Independent | 86,663 | 6% | ||||||||

| 2010 | Jim Rogers | 265,519 | 26% | Tom Coburn (incumbent) | 716,347 | 71% | Stephen Wallace | Independent | 25,048 | 2% | Ronald Dwyer | Independent | 7,807 | 1% |

Books

[edit]- Breach of Trust: How Washington Turns Outsiders Into Insiders. Nashville: WND Books. 2003. ISBN 9780785262206. (with John Hart)

- The Debt Bomb: A Bold Plan to Stop Washington from Bankrupting America. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. 2012. ISBN 978-1595554673. (with John Hart)

- Smashing the DC Monopoly: Using Article V to Restore Freedom and Stop Runaway Government. WND Books. 2017. ISBN 9781944229757.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (August 16, 2011). "Coburn reaffirms term-limit pledge, won't run in 2016". thehill.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ Murphy, Sean (January 17, 2014). "Okla. Sen. Coburn to Retire After Current Session". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Ford, Dana (January 16, 2014). "Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn to retire". CNN. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Murphy, Sean (March 28, 2020). "Ex-Sen. Tom Coburn, conservative political maverick, dies". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Mark, David (March 28, 2020). "Ex-Sen. Tom Coburn, who pressed Republicans to keep budget-cutting promises, dies at 72". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Dinan, Stephen (March 28, 2020). "Tom Coburn leaves lasting legacy for taxpayers". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Paul Kane (January 22, 2014). "In Oklahoma Senate race, establishment Republicans battling far-right conservatives". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Romano, Lois. "GOP Senate Race Intensifies in Okla.". Archived December 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post, July 17, 2004

- ^ Jennifer Steinhauer (July 23, 2011). "A Rock-Solid Conservative Who's Willing to Bend". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Schlesinger, Robert (September 13, 2004). "Medicine man". Salon.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2005.

- ^ a b c Hulse, Carl (July 28, 2008). "Democrats Try to Break Grip of the Senate's 'Dr. No'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c McFadden, Robert D. (March 28, 2020). "Tom Coburn, the 'Dr. No' of Congress, Is Dead at 72". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Paige Winfield (April 20, 2015). "Former Sen. Coburn on what's 'disgusting' about Washington". Washington Examiner. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "Former Senator Tom Coburn Joins Manhattan Institute as Senior Fellow". Manhattan Institute. December 19, 2016. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Persons, Sally (May 23, 2017). "Former Sen. Coburn pushes for Article V Convention to limit federal power". Washington Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (September 3, 2014). "Coburn: Let's change Constitution". The Hill. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Schouten, Fredreka (June 12, 2017). "Exclusive: In latest job, Jim DeMint wants to give Tea Party ' a new mission'". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 27, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ "coburn". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Oral Roberts Evangelistic Association (August 10, 2009). "Abundant Life: 1985-1988". Abundant Life. Vol. 39–42. p. 40.

- ^ a b c Barnard, Matt (August 14, 2014). "Coburn given rousing ovation during last town hall with constituents". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "Three Republicans' quest for Senate Coburn promises to shake up Senate". Oklahoman.com. July 18, 2004. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "The Eve of a New Era". Oklahoman.com. November 9, 1995. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "Opera Star Sarah Coburn Sings For Hundreds Of Oklahoma School Kids". www.newson6.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "Dr. Tom A. Coburn - Accounting (1970)". Oklahoma State University. November 2014. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ David Austin. "Delivering Babies and Legislation: The anatomy of Sen. Tom Coburn's maverick practice of politics." Urban Tulsa Weekly, January 17, 2007

- ^ a b Clayton Bellamy, "Allegations of Medicaid fraud, sterilization haunt Senate candidate in Oklahoma," Associated Press, September 15, 2004

- ^ "United States Senator Tom Coburn :: About Senator Coburn". Coburn.senate.gov. November 2, 2004. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Michael Barone with Richard E. Cohen, The Almanac of American Politics, 2006, page 1370

- ^ Lois Romano. "Woman Who Sued Coburn Goes Public," The Washington Post, September 17, 2004

- ^ Gizzi, John (September 27, 2004). "Coburn Badgered With Dismissed Suit". Human Events. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2006.

- ^ "Tom Coburn, the Republican Senate candidate from Oklahoma, is a strong conservative," National Review, October 11, 2004 v56 i19 p8

- ^ Cox, Matthew Rex. "Coburn, Thomas Allen (1948– )". OKhistory.com. Oklahoma History Center. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "Washington Post Votes Database". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ "Oklahoma State Election Board - Error 404". ok.gov. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008.

- ^ "General Election Results 11/3/98". Ok.gov. November 3, 1998. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Political Realities". Ldjackson.net. August 10, 2008. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Adam (March 28, 2020). "Tom Coburn, unyielding 'Dr. No' of the House and Senate, dies at 72". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Myers, Jim (January 29, 2000). "Coburn endorses Keyes for 'moral leadership'". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ Krehbiel, Randy (March 28, 2020). "Former U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn, whose election signaled a tipping point in Oklahoma politics, dies at 72". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "PACHA Letter to President Bush Calls for 'Immediate' Strategy to Decrease New HIV Infections in U.S." Kaiser Health News. May 20, 2002. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "Gop Lawmaker Blasts Nbc For Airing 'Schindler'S List'". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. February 26, 1997. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Carter, Bill (February 27, 1997). "TV Notes – TV Notes". NYTimes.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Milwaukee Journal Sentinel - Google News Archive Search". google.com.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Elizabeth, Mary (September 8, 2009). "Meet the knuckleheads of the U.S. Senate – U.S. Senate". Salon.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Rich, Frank (July 19, 2009). "They Got Some 'Splainin' to Do". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Tim (February 27, 1997). "'Schindler'S List' Critic Apologizes Politicians Come To Defense Of Nbc'S Broadcast Of Film". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Rep. Coburn Apologizes; Speech Complained of Movie's Sex, Violence – The Washington Post". February 27, 1997. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Losing Sight Of The Big Picture". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. March 4, 1997. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Booknotes interview with Coburn on Breach of Trust: How Washington Turns Outsiders Into Insiders, November 23, 2003 Archived April 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, C-SPAN

- ^ Martindale, Rob (October 4, 2004). "Carson, Coburn in U.S. spotlight". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "Election 2004". Cnn.com. April 13, 1970. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Rivkin, David (January 16, 2014). "Tom Coburn won't serve rest of term – Alexander Burns and Burgess Everett". Politico.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "S. 2270 – All Actions". United States Congress. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "The bucks stop here – Ryan Grim". Politico.Com. December 11, 2007. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Jim Myers, "Coburn still blocking bill: The Oklahoma senator says the cost of the veterans bill should be offset by cuts elsewhere" Archived October 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Tulsa World, November 10, 2009.

- ^ Rick Maze, "Sen. blocking bill: Objection is cost, not vets", Army Times, November 5, 2009.

- ^ McNutt, Michael (February 27, 2010). "Tom Coburn asked to end block on Uganda bill". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ David A. Fahrenthold (May 23, 2007). "Bill to honor Rachel Carson Blocked". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- ^ Stephen Moore (September 19, 2006). "Doctor Tom's DDT Victory". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 30, 2007.

- ^ Hunter, Kathleen (July 28, 2008). "Democrats Unable to Thwart Coburn as Senate 'Tomnibus' Fails Critical Vote". Congressional Quarterly. Archived from the original on November 27, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ Advancing America's Priorities Act

- ^ "S. 3297 (110th): Advancing America's Priorities Act". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Lewis and Clark Mount Hood Wilderness Act of 2007

- ^ "Mt. Hood runs into a senator: Oklahoma's Dr. No | PDX Green – OregonLive.com". Blog.oregonlive.com. March 10, 2008. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Hotmail, Outlook en Skype inloggen - Laatste nieuws - MSN Nederland". Retrieved November 27, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Oklahoma senator once again holds up Mount Hood legislation | Oregon Environmental News". OregonLive.com. November 15, 2008. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Boston Globe: Tom Coburn's position on the Genetic Discrimination Bill". Boston.com. May 2, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Sen. Tom Coburn blocks bill backed by Inhofe". NewsOK.com. January 30, 2010. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Coburn Said Yes: The Oklahoma City Holdout". HuffPost. May 12, 2010. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Hennessey, Kathleen (July 9, 2009). "Husband of Ensign's ex-mistress says Nevada senator paid more than $96,000 severance."[permanent dead link] Star Tribune and AP. Retrieved on July 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Maddow, Rachel (July 10, 2009). Excerpt on the Family Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Rachel Maddow Show. Retrieved on July 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Roig-Franzia, Manuel (June 25, 2009). "The Political Enclave That Dare Not Speak Its Name: The Sanford and Ensign Scandals Open a Door On Previously Secretive 'C Street' Spiritual Haven". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Thrush, Glenn (July 8, 2009). "Ensign "letter" to mistress: I used you for "pleasure"". Politico. Archived from the original on July 11, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (July 10, 2009)."Ensign's Future Remains Unclear" Archived July 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. CBS News. Retrieved on July 19, 2009.

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric; Lipton, Eric (October 1, 2009). "Senator's Aid After Affair Raises Flags Over Ethics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "REPORT OF THE PRELIMINARY INQUIRY INTO THE MATTER OF SENATOR JOHN E. ENSIGN" (PDF). U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "Item Not Found — SFGate". Sfgate.com. March 5, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Strickland, Ruth Ann. "Whistleblowers". The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Beutler, Brian (October 4, 2007). "Blackwater and the Politics of Whistleblowing". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Senator Tom Coburn's Oversight Action :: Latest News". Coburn.senate.gov. September 7, 2007. Archived from the original on July 31, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Senator Tom Coburn's Oversight Action :: Issues". Coburn.senate.gov. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Senator Tom Coburn's Oversight Action :: Submit a Tip". Coburn.senate.gov. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Tom Coburn Joins Campaign Against Muslim Group". TPM. November 18, 2009. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Doyle, Michael, "Judge: Controversial 'Muslim Mafia' used stolen papers," Charlotte Observer[permanent dead link], November 10, 2009, accessed November 17, 2009

- ^ "National Science Foundation: Under the Microscope" Archived June 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, May 26, 2011

- ^ "Dr. Coburn Releases New Oversight Report Exposing Waste, Mismanagement at the National Science Foundation" Archived June 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, May 26, 2011

- ^ JENNY MANDEL of Greenwire (May 26, 2011). "Sen. Coburn Sets Sight on Waste, Duplication at Science Agency". NYTimes.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Office of Sen. Tom Coburn (April 7, 2010). "Senate Report Finds Billions In Waste On Science Foundation Studies". Fox News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Boyle, Alan. "Cosmic Log – Funny science sparks serious spat". MSNBC. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Pear, Robert (March 22, 2012). "Insider Trading Ban for Lawmakers Clears Congress". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Dr. Coburn Votes Against STOCK Act – Press Releases – Tom Coburn, M.D., United States Senator from Oklahoma". Coburn.senate.gov. December 17, 2012. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "RU-486 Abortion Pill: Developments during 1999 & 2000". Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ Cohen, Richard (December 14, 2004). "Democrats, Abortion and 'Alfie'". washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Quindlen, Anna. "Life Begins at Conversation (page 2)". Newsweek. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ a b c Sullum, Jacob (July 1, 2010) What About Tom Coburn's 'Expansive View of the Commerce Clause'? Archived January 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Reason

- ^ Kopel, David and Reynolds, Glenn, Taking Federalism Seriously: Lopez and the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act Archived December 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Connecticut Law Review, Fall 1997, 30 Conn. L. Rev. 59

- ^ a b Milbank, Dana (September 13, 2005). "A Day of Firsts, Overshadowed". The Washington Post. p. A07. Archived from the original on October 26, 2005. Retrieved July 16, 2006.

- ^ "TDS on the Roberts Hearing". Crooks and Liars. September 14, 2005. Archived from the original on April 19, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2006.

- ^ "Transcript: Day Three of the Roberts Confirmation Hearings". The Washington Post. September 14, 2005. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2006.

- ^ Carney, Tim (March 9, 2011) Tom Coburn's tax hike? The ethanol subsidy and the complexities of corporate welfare, Washington Examiner

- ^ "Tom Coburn Labels Himself a "Global Warming Denier" - The Atlantic". June 1, 2021. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status - 109th Congress (2005 - 2006) - H.R.3058 - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. November 30, 2005. Archived from the original on October 14, 2005. Retrieved October 29, 2005.

- ^ Coburn, Tom (June 2009). "100 Stimulus Projects: A Second Opinion". United States Senate. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original on April 23, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ "McCain calls for spending offsets to ensure fiscal responsibility". October 25, 2005. Archived from the original on July 27, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2006.

- ^ Group of senators backs federal pay freeze Archived May 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Government Executive, Karen Rutzig, October 28, 2005. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Congressional Record Senate April 6, 2006 S3239".

- ^ "Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006 (S. 2590) Summary". congress.gov. September 26, 2006. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Casteel, Chris (January 30, 2006). "Coburn plans to scrutinize projects". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ Brendan Dougherty, Michael (July 24, 2007). "Omaha Company's Windfall, Hiring of Lawmaker's Son Irks Senator". Fox News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ ^ Omaha World Herald editorial August 16, 2007, The Oklahoman, June 8, 2007, Senator attacks 'pork'; State avoids extra trims from Coburn

- ^ Text of HIV Prevention Act Archived January 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ Letter to National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, May 18, 2010, page 6 Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tom Coburn". National Journal. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Raju, Manu. "Senate Republicans clash with Grover Norquist." Archived June 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Politico, June 14, 2011.

- ^ O'Donnell, Lawrence. "Republicans revolt on taxes." Archived August 7, 2019, at the Wayback Machine MSNBC, June 16, 2011.

- ^ "GOP senator outlines $68 billion in defense cuts from 'Department of Everything'"[permanent dead link]. Associated Press. November 15, 2012.

- ^ Wilkie, Christina (May 20, 2013). "Oklahoma Senators Jim Inhofe, Tom Coburn, Face Difficult Options On Disaster Relief" Archived November 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Huffington Post.

- ^ Coburn, Tom. "Issue Statements – Second Amendment". U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ "Read The Bill: H.R. 627". GovTrack.us. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ Lillis, Mike (May 12, 2009). "Senate Approves Coburn Gun Amendment...in Credit Card Bill". The Washington Independent. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ "Gun Games in the Senate". The New York Times. October 1, 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ O'Keefe, Ed (January 25, 2013). "Tom Coburn talking with Democrats about background check bill". Washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Bolton, Alexander (July 22, 2012). "Donation to Manchin is new fodder in feud between Norquist, Sen. Coburn". The Hill. Retrieved July 13, 2016.[dead link]

- ^ Bresnahan, John (March 6, 2013). "Schumer ends gun talks with Coburn". Politico. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Silver, Nate (April 18, 2013). "Modeling the Senate's Vote on Gun Control". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Health Care – Tom Coburn, M.D., United States Senator from Oklahoma Archived June 10, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grace-Marie Turner And Joseph R. Antos (May 20, 2009). "The GOP's Health-Care Alternative – WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status - 111th Congress (2009 - 2010) - S.1099 - CRS Summary - THOMAS (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. May 20, 2009. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Myers, Jim (May 22, 2005). "Coburn, Inhofe ready for end to nominee drama". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Tom Coburn On the Issues". On The Issues. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote". Senate.gov. Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Coburn declines to elaborate on Iraq War statement". Tulsa World. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- ^ "Tom Coburn stalls veterans-suicide bill in Senate". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Coburn, Tom (February 24, 2015). "A means to smite the federal Leviathan". Washington Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ Ward, Jon (February 5, 2014). "Tom Coburn Decides Only A Constitutional Convention Can Fix Washington". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ Coburn, Tom (2017). Smashing the DC Monopoly: Using Article V to Restore Freedom and Stop Runaway Government. WND Books. ISBN 9781944229757.

- ^ "Senator Tom Coburn, M.D. - BRI mourns passing of dedicated Board member". BRI. March 29, 2020. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Tom Coburn, Patrick Leahy among winners of Jefferson Awards". Politico. Associated Press. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Jonathan Alter, The Promise: President Obama, Year One

- ^ The President has a friend on right flank Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, TheHill.com

- ^ "Coburn Talks About Obama". Politicalwire.com. April 8, 2011. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2011.

- ^ Ben Evans, "Senator Tom Coburn to Sing 'Rocket Man'", AP at ABC News, January 14, 2009.

- ^ Koplan, Tal (January 28, 2014). "Obamacare: Tom Coburn loses cancer doctor". Politico. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Kliff, Sarah (January 28, 2014). "Did Sen. Coburn lose his cancer doctor because of Obamacare?". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "Coburn says ObamaCare cost him coverage for cancer doctor". Fox News. January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ Casteel, Charlie (March 28, 2020). "Former U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn dies at 72". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ News On 6. "Memorial Service Held For Former Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn". newson6.com. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Election Statistics". Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 25, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Voices of Oklahoma interview. First person interview conducted on May 4, 2016, with Tom Coburn.

- 1948 births

- 2020 deaths

- 20th-century Oklahoma politicians

- 21st-century Oklahoma politicians

- American obstetricians

- Baptists from Oklahoma

- Deaths from cancer in Oklahoma

- Deaths from prostate cancer in the United States

- Manhattan Institute for Policy Research

- Oklahoma State University alumni

- Physicians from Oklahoma

- Politicians from Casper, Wyoming

- Politicians from Muskogee, Oklahoma

- Republican Party United States senators from Oklahoma

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Oklahoma

- Southern Baptists

- University of Oklahoma alumni