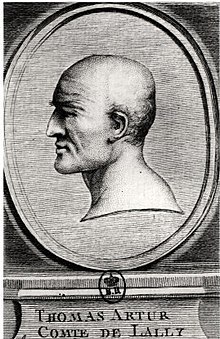

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally

Thomas Arthur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 January 1702 Romans-sur-Isere, Dauphine, France |

| Died | 9 May 1766 (aged 64) Paris, France |

| Allegiance | France |

| Years of service | 1721-1761 |

| Battles / wars | |

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally, baron de Tollendal (13 January 1702 – 9 May 1766) was a French general of Irish Jacobite ancestry. Lally commanded French forces, including two battalions of his own red-coated Regiment of Lally of the Irish Brigade, in India during the Seven Years' War. After a failed attempt to capture Madras he lost the Battle of Wandiwash to British forces under Eyre Coote and then was forced to surrender the remaining French post at Pondicherry.

After time spent as a prisoner of war in Britain, Lally voluntarily returned to France to face charges where he was beheaded for his alleged failures in India. Ultimately the jealousies and disloyalties of other officers, together with insufficient resources and limited naval support prevented Lally from securing India for France. In 1778, he was publicly exonerated by Louis XVI from his alleged crime.

Life

[edit]He was born at Romans-sur-Isère, Dauphiné,[1] the son of Sir Gerald Lally,[2] an Irish Jacobite from Tuam, County Galway, who married a French lady of noble family.[3] His title is derived from the Lally ancestral home, Castel Tullendally in County Galway,[1] where the Lallys (originally O'Mullally) were prominent members of the Gaelic aristocracy who could trace their ancestry back to the second-century High King of Ireland, Conn of the Hundred Battles.

Entering the French army in 1721, he served in the War of the Polish Succession against Austria; he was present at the Battle of Dettingen,[4] and commanded the regiment de Lally in the famous Irish brigade at Fontenoy (May 1745).[5] He was made a brigadier on the field by Louis XV.[3]

He was a staunch Jacobite and in 1745 accompanied Charles Edward Stuart (then known in Jacobite circles as the Prince Regent, or Bonnie Prince Charlie) to Scotland, serving as aide-de-camp at the Battle of Falkirk Muir.[6] Escaping to France, he served with Marshal Saxe in the Low Countries, and at the Siege of Maastricht (1748) was made a maréchal de camp.[3]

When war broke out with Britain again in 1756, Lally was appointed governor-general of French India and commanded a French expedition to India, made up of four battalions, two of which were from his own Regiment of Lally of the Irish Brigade. He reached Pondicherry in April 1758,[3] and within six weeks had pushed the British back from the coast to Madras (in modern-day Chennai), the headquarters of the English East India Company.

He was a man of courage and a capable general, but his pride and ferocity made him unpopular with his officers and men.[7] He was unsuccessful in an attack on Tanjore, and as he lacked French naval support he had to retire from the Siege of Madras upon the arrival of the British fleet. He was defeated by Sir Eyre Coote at the Battle of Wandiwash, and besieged in Pondicherry, where he was forced to capitulate in 1761.[3][8]

Trial and execution

[edit]

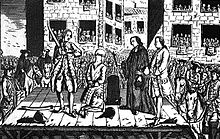

Lally was sent as a prisoner of war to England. Public opinion in France was very hostile, blaming him for the defeat by the British, and there were widespread calls for Lally to be put on trial.[9] While in London, he heard that he was accused in France of treason, and insisted, against advice, on returning on parole to stand trial.[9] He was kept prisoner for nearly two years before the trial began in 1764[3] and when the Advocate General of the Parlement of Paris, Joly de Fleury, began the prosecution, Lally had not received any documentation of the charges, and was not allowed a defence lawyer. Throughout the trial, which lasted for two years, Lally fought against Joly de Fleury's charges but on 6 May 1766 he was convicted and sentenced to be beheaded by Charles-Henri Sanson.[9]

Lally made an attempt at suicide after his sentencing, and three days after his conviction he was gagged to prevent him from protesting his innocence further. He was transported in a garbage cart to be beheaded at the Place de Grève. The memoirs of the Sanson family record many details of the execution. According to the Sansons, after Lally said "And now, you can strike!" Charles Henri raised his weapon but failed to sever the old man's head in one blow. Lally reportedly rose to his feet, and Charles Henri's father intervened to complete the execution hastily as he promised Lally 35 years prior to this day. It is reported that Charles Jean-Baptiste Sanson finished Lally with a single strike after immediately recovering from the stroke-like condition that plagued him for years.[10] It is highly unlikely that Charles Jean-Baptiste Sanson regained his strength to save the day. A piece written by Dr. Louis, as cited in Daniel Arasse's "The Guillotine and the Terror," recounts that during the execution, Lally knelt blindfolded and Charles-Henri Sanson struck him on the back of the neck. The blow failed to separate the head from the body, causing Lally to fall forwards. Finally, the head was detached from the body with four or five saber blows, which was witnessed with horror.[11]

Progeny

[edit]By one Felicity Crofton,[12] Lally had a legitimised son and heir, Trophime-Gérard, later Marquis de Lally-Tollendal, a distinguished French statesman who (as further described below) subsequently devoted much time and energy to the rehabilitation of his father's memory. Lally also had a natural daughter, Henrietta (or Harriet), who lived in Madras[13] and died on 9 September 1836.[14]

Voltaire's efforts at rehabilitation

[edit]Voltaire knew Lally personally, and had no liking for him. As he had investments in the East India Company, he was concerned 'this Irish hothead' might not be good for the shareholders when he was sent out to India.[15] When he heard of his execution, he wrote to one friend, "I knew Lally-Tollendal for an absurd man, violent, ambitious, capable of pillage and abuse of power; but I should be astonished if he was a traitor", and to another he wrote, "I have just been reading up on the tragedy of poor Lally. I can easily see that Lally got himself detested by all the officers and all the inhabitants of Pondicherry, but in all the submissions to the trial there is no appearance of embezzlement, nor of treason."[16] Voltaire had taken up a number of campaigns against miscarriages of justice, most famously that of Jean Calas. His work to expose injustice and abuse of process was often hindered by the unwillingness of the courts and other authorities to release evidence, statements, and court records. In this case too, although Voltaire wanted to investigate further, he was unable to penetrate the institutional secrecy of the court for the time being.

Voltaire was able to take no further action until in 1770 he was approached for help by Lally's natural son Gérard de Lally-Tollendal. There is an account that the shame of military failure was originally so great that this son was brought up in total ignorance of who his father had been, and only inadvertently discovered the truth of his background at the age of fifteen.[17] However this account cannot be true, as the son was fifteen when his father was executed,[18] so his origins must have been concealed for other reasons. Voltaire offered what assistance he could, but the campaign to release the court documents was painfully slow.

Louis XV tried to throw the responsibility for what was undoubtedly a judicial murder on his ministers and the public, but his policy needed a scapegoat, and he was probably well content not to exercise his authority to save an almost friendless foreigner.[3] The family records of his executioner stated that, while the charge of treason was clearly baseless, those of abuse of power, violence against the administrators of the colony and his soldiers, and cruelty to the natives, had ample witnesses. Lally had so impeached his officers and administrators of the colony that they could only feel safe by his condemnation and death.[19]

When Louis XVI came to the throne in 1774 there was more inclination towards clemency. Still, it took discussion in thirty-two sessions before, in 1778, the Royal Council agreed to annul the proceedings against Lally, though the case still had to be referred to the Parlement of Rouen for formal overturning.[20] On 24 May 1778, less than a week before he died, Voltaire learned that Gérard de Lally-Tollendal had been given leave to appeal. Deeply moved, Voltaire wrote to him: "The dying man has been revived by learning this great news; he embraces M. de Lally very tenderly; he sees that the king is the defender of justice. He will die content." It was the last letter he wrote.[21]

The sentence was not overturned until 1781, and the conviction itself was never cleared.

When the case was considered by the Parlement de Paris, the orator Jean-Jacques d'Eprémesnil acted as spokesman of Parlement and refused to consider any rehabilitation for Lally.[22]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b O'Callaghan (1870), p. 346.

- ^ John O'Donovan (1862), The Topographical Poems of John O'Dubhagain and Giolla na Noamh O'Huidhrin, Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lally, Thomas Arthur, Comte de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 95.

- ^ O'Callaghan (1870), p. 349.

- ^ Thomas Osborne Davis (1866), The Poems of Thomas Davis, D. & J. Sadlier & Company, p. 249.

- ^ Stephen McGarry (2013), Irish Brigades Abroad: From the Wild Geese to the Napoleonic Wars, The History Press.

- ^ S. N. Sen (2006), History of Modern India, New Age International, p. 35.

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 159. ISBN 9788131300343.

- ^ a b c Davidson (2010), p. 359.

- ^ Sanson (1876).

- ^ Arasse (1989), p. 186.

- ^ John O'Donovan, The Tribes and Customs of Hy-Many, commonly called O'Kelly's Country (Dublin, 1843) at page 182

- ^ Diary of Colonel Bayly: 12th Regiment, 1796-1830 (London, 1896), at page 46

- ^ The Bengal Obituary (Calcutta, 1851), at page 201

- ^ Davidson (2010), p. 358.

- ^ Davidson (2010), p. 360.

- ^ Schama (1989), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Frederick Dixon (1893). "Lally's Visit to England in 1745". The English Historical Review. VIII (30): 284.

- ^ Memoirs of the Sansons, from private notes and documents, 1688-1847, edited by Henry Sanson. Available from Archive.org, accessed 20 April 2016

- ^ Schama (1989), p. 32.

- ^ Davidson (2010), p. 438.

- ^ J. Charles (1803). Historical Pictures of the French Revolution, Paris, p.18, accessed 15/02/2017

References and further reading

[edit]- Arasse, Daniel (1989). The Guillotine and the Terror, Trans. Christopher Miller. Penguin.

- Davidson, Ian (2010). Voltaire, A Life. London: Profile Books.

- Malleson, G. B. (1865). The Career of Count Lally.

- McGarry, S. (2013). Irish Brigades Abroad. Dublin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - O'Callaghan, John Cornelius (1870). History of the Irish Brigades in the Service of France: From the Revolution in Great Britain and Ireland Under James II to the Revolution in France Under Louis XVI. Glasgow: Cameron and Ferguson.

- O’hAnnrachain, E. (2004). "Lally, the Regime's Scapegoat". The Irish Sword. 24.

- Sanson, Henry, ed. (1876). Memoirs of the Sansons, from Private Notes and Documents (1688-1847). London: Chatto & Windus.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens. Penguin.

- Voltaire's Œuvres complètes

- "Z's" article "The Marquis de Lally-Tollendal" in the Biographie Michaud

- The legal documents are preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale

- 1702 births

- 1766 deaths

- People from Romans-sur-Isère

- French generals

- Governors of French India

- Counts of Lally-Tollendal

- French people of Irish descent

- People executed for treason against France

- People executed by France by decapitation

- Earls in the Jacobite peerage

- People executed by the Ancien Régime in France

- Executed French people

- French prisoners of war in the 18th century

- 18th-century executions by France