Cavendish Laboratory

Cavendish plaque at original New Museums Site | |

| Established | 1874 |

|---|---|

| Affiliation | University of Cambridge |

| Head of department | Mete Atature[1] |

| Location | , United Kingdom 52°12′33″N 00°05′33″E / 52.20917°N 0.09250°E |

| Cavendish Professor of Physics | Vacant |

| Website | www |

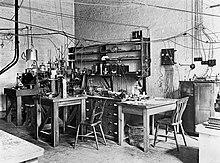

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named after the British chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish. The laboratory has had a huge influence on research in the disciplines of physics and biology.

The laboratory moved to its present site in West Cambridge in 1974.

As of 2019[update], 30 Cavendish researchers have won Nobel Prizes.[2] Notable discoveries to have occurred at the Cavendish Laboratory include the discovery of the electron, neutron, and structure of DNA.

Founding

[edit]

The Cavendish Laboratory was initially located on the New Museums Site, Free School Lane, in the centre of Cambridge. It is named after British chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish[3][4] for contributions to science[5] and his relative William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire, who served as chancellor of the university and donated funds for the construction of the laboratory.[6]

Professor James Clerk Maxwell, the developer of electromagnetic theory, was a founder of the laboratory and the first Cavendish Professor of Physics.[7] The Duke of Devonshire had given to Maxwell, as head of the laboratory, the manuscripts of Henry Cavendish's unpublished Electrical Works. The editing and publishing of these was Maxwell's main scientific work while he was at the laboratory. Cavendish's work aroused Maxwell's intense admiration and he decided to call the Laboratory (formerly known as the Devonshire Laboratory) the Cavendish Laboratory and thus to commemorate both the Duke and Henry Cavendish.[8][9]

Physics

[edit]Several important early physics discoveries were made here, including the discovery of the electron by J.J. Thomson (1897) the Townsend discharge by John Sealy Townsend, and the development of the cloud chamber by C.T.R. Wilson.

Ernest Rutherford became Director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919. Under his leadership the neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, and in the same year the first experiment to split the nucleus in a fully controlled manner was performed by students working under his direction; John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton.

Physical chemistry

[edit]Physical Chemistry (originally the department of Colloid Science led by Eric Rideal) had left the old Cavendish site, subsequently locating as the Department of Physical Chemistry (under RG Norrish) in the then new chemistry building with the Department of Chemistry (led by Lord Todd) in Lensfield Road: both chemistry departments merged in the 1980s.

Nuclear physics

[edit]In World War II the laboratory carried out research for the MAUD Committee, part of the British Tube Alloys project of research into the atomic bomb. Researchers included Nicholas Kemmer, Alan Nunn May, Anthony French, Samuel Curran and the French scientists including Lew Kowarski and Hans von Halban. Several transferred to Canada in 1943; the Montreal Laboratory and some later to the Chalk River Laboratories. The production of plutonium and neptunium by bombarding uranium-238 with neutrons was predicted in 1940 by two teams working independently: Egon Bretscher and Norman Feather at the Cavendish and Edwin M. McMillan and Philip Abelson at Berkeley Radiation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Biology

[edit]The Cavendish Laboratory has had an important influence on biology, mainly through the application of X-ray crystallography to the study of structures of biological molecules. Francis Crick already worked in the Medical Research Council Unit, headed by Max Perutz[10][11] and housed in the Cavendish Laboratory, when James Watson came from the United States and they made a breakthrough in discovering the structure of DNA. For their work while in the Cavendish Laboratory, they were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962, together with Maurice Wilkins of King's College London, himself a graduate of St. John's College, Cambridge.

The discovery was made on 28 February 1953; the first Watson/Crick paper appeared in Nature on 25 April 1953. Sir Lawrence Bragg, the director of the Cavendish Laboratory, where Watson and Crick worked, gave a talk at Guy's Hospital Medical School in London on Thursday 14 May 1953 which resulted in an article by Ritchie Calder in the News Chronicle of London, on Friday 15 May 1953, entitled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life." The news reached readers of The New York Times the next day; Victor K. McElheny, in researching his biography, Watson and DNA: Making a Scientific Revolution, found a clipping of a six-paragraph New York Times article written from London and dated 16 May 1953 with the headline "Form of `Life Unit' in Cell Is Scanned." The article ran in an early edition and was then pulled to make space for news deemed more important. (The New York Times subsequently ran a longer article on 12 June 1953). The Cambridge University undergraduate newspaper Varsity also ran its own short article on the discovery on Saturday 30 May 1953. Bragg's original announcement of the discovery at a Solvay Conference on proteins in Belgium on 8 April 1953 went unreported by the British press.

Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Dorothy Hodgkin, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton, were some of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Crick and Watson; at the time they were working at the University of Oxford's Chemistry Department. All were impressed by the new DNA model, especially Brenner who subsequently worked with Crick at Cambridge in the Cavendish Laboratory and the new Laboratory of Molecular Biology. According to the late Dr. Beryl Oughton, later Rimmer, they all travelled together in two cars once Dorothy Hodgkin announced to them that they were off to Cambridge to see the model of the structure of DNA.[12] Orgel also later worked with Crick at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Present site

[edit]

Due to overcrowding in the old buildings, it moved to its present site in West Cambridge in the early 1970s.[13] It is due to move again to a third site currently under construction in West Cambridge.[14]

Nobel laureates at the Cavendish

[edit]- John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh (Physics, 1904)

- Sir J. J. Thomson (Physics, 1906)

- Ernest Rutherford (Chemistry, 1908)

- Sir William Lawrence Bragg (Physics, 1915)

- Charles Glover Barkla (Physics, 1917)

- Francis William Aston (Chemistry, 1922)

- Charles Thomson Rees Wilson[15] (Physics, 1927)

- Arthur Compton (Physics, 1927)

- Sir Owen Willans Richardson (Physics, 1928)

- Sir James Chadwick (Physics, 1935)

- Sir George Paget Thomson[16] (Physics, 1937)

- Sir Edward Victor Appleton (Physics, 1947)

- Patrick Blackett, Baron Blackett (Physics, 1948)

- Sir John Cockcroft[17] (Physics, 1951)

- Ernest Walton (Physics, 1951)

- Francis Crick (Physiology or Medicine, 1962)

- James Watson (Physiology or Medicine, 1962)

- Max Perutz (Chemistry, 1962)

- Sir John Kendrew (Chemistry, 1962)

- Dorothy Hodgkin[18] (Chemistry, 1964)

- Brian Josephson (Physics, 1973)

- Sir Martin Ryle (Physics, 1974)

- Antony Hewish (Physics, 1974)

- Sir Nevill Francis Mott (Physics, 1977)

- Philip Warren Anderson (Physics, 1977)

- Pyotr Kapitsa (Physics, 1978)

- Allan McLeod Cormack (Physiology or Medicine, 1979)

- Mohammad Abdus Salam (Physics, 1979)

- Sir Aaron Klug[19] (Chemistry, 1982)

- Didier Queloz (Physics, 2019)

Cavendish Professors of Physics

[edit]The Cavendish Professors were the heads of the department until the tenure of Sir Brian Pippard, during which period the roles separated.

- James Clerk Maxwell 1871–1879

- John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh[20] 1879–1884

- Sir Joseph J. Thomson 1884–1919

- Ernest Rutherford 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson 1919–1937

- Sir William Lawrence Bragg 1938–1953

- Sir Nevill Francis Mott 1954–1971

- Sir Brian Pippard[21] 1971–1984

- Sir Sam Edwards 1984–1995

- Sir Richard Friend[22] 1995–2020

- Vacant 2020–present

Heads of department

[edit]- Professor Sir Alan Cook 1979–1984

- Professor Archie Howie 1989–1997

- Professor Malcolm Longair† 1997–2005

- Professor Peter Littlewood 2005–2011

- Professor James Stirling† 2011–2013

- Professor Michael Andrew Parker 2013–2023

- Professor Mete Atature 2023 –

† Jacksonian Professors of Natural Philosophy

Cavendish Groups

[edit]Areas in which the Laboratory has been influential include:-

- Shoenberg Laboratory for Quantum Matter,[23] led by Gil Lonzarich[24]

- Superconductivity Josephson junction, led by Brian Pippard[21]

- Theory of Condensed Matter,[25] which is the dominant theoretical group.

- Electron Microscopy Group [26] led by Archie Howie

- Radio Astronomy (led by Martin Ryle[27] and Antony Hewish), with the Cavendish Astrophysics Groups telescopes being based at Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory.

- Semiconductor Physics[28]

- Atomic, Mesoscopic and Optical Physics (AMOP) Group[29] led by Zoran Hadzibabic

- Nanophotonics group[30] led by Jeremy Baumberg

- Structure and Dynamics Group,[31] led by Jacqui Cole

- Laboratory for Scientific Computing[32] led by Nikos Nikiforakis

- Biological and Soft Systems Group[33] led by Pietro Cicuta

Cavendish staff

[edit]As of 2023[update] the laboratory is headed by Mete Atature.[1] The Cavendish Professor of Physics is Sir Richard Friend.[22]

Notable senior academic staff

[edit]As of 2015[update] senior academic staff (professors or readers) include:[34]

- Jeremy Baumberg, Professor of Nanoscience and Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge

- Jacqui Cole, Professor of Molecular Engineering

- Athene Donald, Professor of Experimental Physics, Master of Churchill College, Cambridge

- Sir Richard Friend, Cavendish Professor of Physics and Fellow of St John's College, Cambridge

- Stephen Gull, University Professor of Physics

- Sir Michael Pepper, Honorary Professor of Pharmaceutical Science in the University of Otago, New Zealand

- Didier Queloz, professor at the Battcock Centre for Experimental Astrophysics

- James Floyd Scott, professor and director of research

- Ben Simons, Herchel Smith Professor of Physics

- Henning Sirringhaus, Hitachi Professor of Electron Device Physics and head of Microelectronics and Optoelectronics Group

- Sarah Teichmann, principal research associate and Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge

Notable emeritus professors

[edit]The Cavendish is home to a number of emeritus scientists, pursuing their research interests in the laboratory after their formal retirement.[34]

- Mick Brown, emeritus professor

- Volker Heine, emeritus professor

- Brian Josephson, emeritus professor

- Archibald Howie, emeritus professor

- Malcolm Longair, Emeritus Jacksonian Professor of Natural Philosophy

- Gil Lonzarich, Emeritus Professor of Condensed Matter Physics and professorial fellow at Trinity College, Cambridge

- Bryan Webber, Emeritus Professor of Theoretical High Energy Physics and professorial fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Other notable alumni

[edit]Besides the Nobel Laureates, the Cavendish alumni include:

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Professor of Physics, Fellow, Director of Studies and Tutor at St. John's College". University of Cambridge. 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Nobel Prize Winners who have worked for considerable periods of time at the Cavendish Laboratory". Archived from the original on 12 January 2006.

- ^ "The History of the Cavendish". University of Cambridge. 13 August 2013. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "A history of the Cavendish laboratory, 1871–1910". 1910.

- ^ "Professor and Laboratory " Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University

- ^ The Times, 4 November 1873, p. 8

- ^ Dennis Moralee, "Maxwell's Cavendish" Archived 2013-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, from the booklet "A Hundred Years and More of Cambridge Physics"

- ^ "James Clerk Maxwell" Archived 2015-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University

- ^ "Austin Wing of the Cavendish Laboratory". Archived from the original on 21 November 2012.

- ^ Blow, D. M. (2004). "Max Ferdinand Perutz OM CH CBE. 19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002: Elected F.R.S. 1954". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 50: 227–256. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2004.0016. JSTOR 4140521. PMID 15768489.

- ^ Fersht, A. R. (2002). "Max Ferdinand Perutz OM FRS". Nature Structural Biology. 9 (4): 245–246. doi:10.1038/nsb0402-245. PMID 11914731.

- ^ Olby, Robert, Francis Crick: Hunter of Life's Secrets, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2009, Chapter 10, p. 181 ISBN 978-0-87969-798-3

- ^ "West Cambridge Site Location of the Cavendish Laboratory on the University map". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Cavendish III – Department of Physics". www.phy.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Blackett, P. M. S. (1960). "Charles Thomson Rees Wilson 1869–1959". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 6. Royal Society: 269–295. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1960.0037. S2CID 73384198.

- ^ Moon, P. B. (1977). "George Paget Thomson 3 May 1892 – 10 September 1975". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 23: 529. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1977.0020.

- ^ Oliphant, M. L. E.; Penney, L. (1968). "John Douglas Cockcroft. 1897–1967". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 14: 139–188. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1968.0007. S2CID 57116624.

- ^ Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. PMID 13678070. S2CID 61764553.

- ^ Amos, L.; Finch, J. T. (2004). "Aaron Klug and the revolution in biomolecular structure determination". Trends in Cell Biology. 14 (3): 148–152. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.01.002. PMID 15003624.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "John William Strutt", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ a b Longair, M. S.; Waldram, J. R. (2009). "Sir Alfred Brian Pippard. 7 September 1920 – 21 September 2008". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 55: 201–220. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2009.0014.

- ^ a b "FRIEND, Sir Richard (Henry)". Who's Who. Vol. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Quantum Matter group". Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ Gilbert George Lonzarich's publications indexed by the Scopus bibliographic database. (subscription required)

- ^ "Theory of Condensed Matter group". Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ "Electron Microscopy Group". Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Graham-Smith, F. (1986). "Martin Ryle. 27 September 1918 – 14 October 1984". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 32: 496–524. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1986.0016. S2CID 71422161.

- ^ "Semiconductor Physics Group". Archived from the original on 8 October 2003. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "AMOP group". Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Nanophotonics Group". Archived from the original on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Structure and Dynamics Group". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "Laboratory for Scientific Computing". Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Biological and Soft Systems". Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Academic staff at the Cavendish Laboratory". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Longair, Malcolm (2016). Maxwell's Enduring Legacy: A Scientific History of the Cavendish Laboratory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08369-1.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Cavendish Laboratory at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cavendish Laboratory at Wikimedia Commons

- Austin Memories—History of Austin and Longbridge Cavendish Article