Upper Galilee

Upper Galilee

| |

|---|---|

A lemon orchard in the Galilee | |

| |

| Coordinates: 32°59′N 35°24′E / 32.983°N 35.400°E | |

| Part of | |

| Native name | |

| Highest elevation | 1,208 m (3,963 ft) |

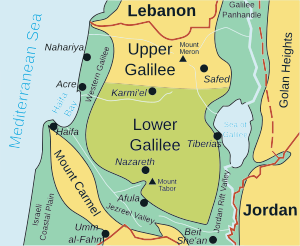

The Upper Galilee (Hebrew: הגליל העליון, HaGalil Ha'Elyon; Arabic: الجليل الأعلى, Al Jaleel Al A'alaa) is a geographical region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Part of the larger Galilee region, it is characterized by its higher elevations and mountainous terrain. The term "Upper Galilee" is ancient, and has been in use since the end of the Second Temple period. From a political perspective, the Upper Galilee is situated within the administrative boundaries of the Northern District of Israel.

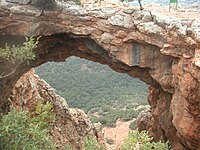

The Upper Galilee is known for its natural beauty, including lush landscapes, Mediterranean forests, and scenic vistas. Significant natural sites include Nahal Amud and the Keshet Cave. It's also an area where vineyards and wineries thrive, producing quality wines. Mount Meron stands as the highest point in the area, reaching an elevation of 1,208 meters above sea level. Safed is a main city in the region and also hosts an artists' quarter that was a major center of Israeli art.[1][2]

Although historical definitions encompass parts of southern Lebanon within the boundaries of the Upper Galilee, the Lebanese government does not use the term "Galilee" for any part of its territory.

Boundaries

[edit]Originally, the term "Upper Galilee" referred to a larger region, encompassing the mountainous regions of what is today northern Israel and southern Lebanon. The boundaries of this region were the Litani River in the north, the Mediterranean Sea in the west, the Lower Galilee in the south (from which it is separated by the Beit HaKerem Valley), and the upper Jordan River and the Hula Valley in the east.[3]

According to the first century Jewish historian Josephus, the bounds of Upper Galilee stretched from Bersabe in the Beit HaKerem Valley to Baca (Peki'in) in the north, and from Meloth to Thella.[4] The extent of this region is approximately 470 km2.[5]

In present-day usage, the toponym mainly refers only to the northern part of the Galilee that is under Israeli sovereignty. That is, the term today does not include the portion of Southern Lebanon up to the Litani River, or the corresponding stretches of the Israeli Coastal Plain to the west, or the Jordan Rift Valley to the east. These are considered to be separate geographical areas that are not part of “Upper Galilee.”[citation needed]

History

[edit]Ancient times

[edit]The Upper Galilee is home to numerous significant ancient synagogues, dating from Roman and Byzantine times. Those include the synagogues of Bar'am,[6] Nabratein,[7] Gush Halav,[8] Huqoq,[9] Chorazin,[10] Meron[11] and a few others. Remains of synagogues has also been found in Qision[12] and Alma.[13]

Modern period

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the Balfour Declaration in which the British Empire promised to create "A Jewish National Home" in Palestine, the Zionist Movement presented to the Versailles Peace Conference a document calling for including in the British Mandate of Palestine the entire territory up to the Litani river — with a view to this becoming eventually part of a future Jewish state.

However, only less than half this area was actually included in British Mandatory Palestine, the final border being influenced both by diplomatic maneuverings and struggles between Britain and France and by fighting on the ground, especially the March 1920 battle of Tel Hai.

For a considerable time after the border was defined so to make the northern portion of the territory concerned part of the French mandated territory that became Lebanon, many Zionist geographers — and Israeli geographers in the state's early years — continued to speak of "The Upper Galilee" as being "the northern sub-area of the Galilee region of Israel and Lebanon".

Under this definition, "The Upper Galilee" covers an area spreading over 1,500 km2, about 700 in Israel and the rest in Lebanon. This included the highland region of Belad Bechara in Jabal Amel located in South Lebanon,[14] which was at for some time known in Hebrew as "The Lebanese Galilee".[3] As defined in geographical terms, "it is separated from the Lower Galilee by the Beit HaKerem valley; its mountains are taller and valleys are deeper than those in the Lower Galilee; its tallest peak is Har Meron at 1,208 m above sea level. Safed is one of the major cities in this region".

In recent decades, however, this usage has virtually disappeared from the general Israeli discourse, the term "Upper Galilee" being used solely in reference to the part located in Israel.

In art

[edit]The Upper Galilee region, specifically the city of Safed was a centre of Israeli and Jewish art since 1920 when the School of Paris painter, Yitzhak Frenkel visited the region and was the first to settle in Safed where he later established an art school.[15][16] In Safed was established the Artists' quarter of Safed. Safed harbored mysticism and was reminiscent of picturesque villages, which drew artists such as Frenkel, Marc Chagall, Moshe Castel, Mordechai Levanon and others.[15][17][18] Artists were drawn to the upper galilee due to its mountainous landscapes and "mysticsm". Prior to the air conditioner, Safed also attracted artists due to its climatic conditions which were more comfortable than Tel Aviv during the summer.[2] Safed also offered different themes for the artists, from the Klezmer musicians to the Hasidim and the city itself.[17][19] Mount Meron was also an object in artworks by Jewish artists with artists such as Frenkel and Rolly Schaffer painting serene or fiery scenes of sunset over the mountain.[17]

Gallery

[edit]-

Mountainous area in the Upper Galilee

-

Ain Ebel in the Lebanese Upper Galilee

-

A view looking north from the top of Har Meron in the Upper Galilee. Parts of southern Lebanon are visible in the background

-

Old road from Rosh Pinna to Safed, Upper Galilee, Israel

-

The Amud river

-

Horses roam in Amud stream, near the Sea of Galilee

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hecht Museum (2013). After the School Of Paris (in English and Hebrew). Israel. ISBN 9789655350272.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Ofrat, Gideon (1987). The Golden Age of Painting in Safed (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Sifriat HaPoalim.

- ^ a b Vilnai, Ze'ev (1976). "Upper Galilee". Ariel Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Vol. 2. Israel: Am Oved. pp. 1364–67.

- ^ M. Aviam & P. Richardson, "Josephus' Galilee in Archaeological Perspective", published in: Mason, Steve, ed. (2001). Life of Josephus. Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary. Vol. 9. BRILL. pp. 179;182. ISBN 9004117938.; Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) II, 577; III, 46 (Wars of the Jews 3.3.1)

- ^ Eric M. Meyers, "Galilean Regionalism as a Factor in Historical Reconstruction," in: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (No. 221, 1976), p. 95

- ^ Aviam, Mordechai (2001-01-01), Avery-Peck, Alan; Neusner, Jacob (eds.), "THE ANCIENT SYNAGOGUES AT BARʿAM", Judaism in Late Antiquity 3. Where we Stand: Issues and Debates in Ancient Judaism, BRILL, pp. 155–177, doi:10.1163/9789004294172_008, ISBN 978-90-04-29417-2, retrieved 2023-09-02

- ^ Eric M. Meyers and Carol Meyers, "Excavations at Ancient Nabratein: Synagogue and Environs," Meiron Excavation Project Reports - MEPR 6, Eisenbrauns, 2009.

- ^ Hachlili, Rachel (2013). "Dating of the Upper Galilee Synagogues". Ancient Synagogues - Archaeology and Art: New Discoveries and Current Research. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1, Ancient Near East; vol. 105 = Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. pp. 586, 588. ISBN 978-90-04-25772-6. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Remains of Roman Period Synagogue Discovered in Galilee, July 2, 2012, Science News

- ^ Avraham Negev; Shimon Gibson (July 2005). Archaeological encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8264-8571-7. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Urman, Dan; Flesher, Paul V.M., eds. (1998). "Ancient Synagogues (2 vols)". Brill: 62–63. doi:10.1163/9789004511323. ISBN 978-90-04-11254-4.

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1976). "Gazetteer of Roman Palestine". Qedem. 5: 89. ISSN 0333-5844. JSTOR 43587090.

- ^ "XXIII. ʿAlma", Volume 5/Part 1 Galilaea and Northern Regions: 5876-6924, De Gruyter, pp. 146–149, 2023-03-20, doi:10.1515/9783110715774-031, ISBN 978-3-11-071577-4, retrieved 2024-02-23

- ^ Salibi, Kamal S. (1988). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 4. ISBN 1-85043-091-8.

- ^ a b ארי, מיכל בן (2009-03-02). "שיר שחלמתי על צפת". Ynet (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2024-10-09.

- ^ Barzel, Amnon (1974). Frenel Isaac Alexandre. Israel: Masada. p. 16.

- ^ a b c Ofrat, Gideon. The Art and Artists of Safed (in Hebrew). pp. 89–90.

- ^ "FRENKEL FRENEL MUSEUM". www.frenkel-frenel.org. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Hecht Museum (2013). After the School Of Paris (in English and Hebrew). Israel. ISBN 9789655350272.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)