University of Missouri

| |

| Latin: Universitas Missouriensis[1] | |

Former names | Missouri State University[2] |

|---|---|

| Motto | Salus populi suprema lex esto (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Let the welfare of the people be the supreme law"[3][4][5] |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | February 11, 1839[6] |

Parent institution | University of Missouri System |

| Accreditation | HLC |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $1.42 billion (2023) (MU only)[7] $2.24 billion (2023) (system-wide)[8] |

| Budget | $1.76 billion (FY 2024)[9] |

| Chancellor | Mun Choi[10] |

| Provost | Matthew Martens[11] |

Academic staff | 4,215 (fall 2023)[12] |

Administrative staff | 6,965 (fall 2023)[12] |

| Students | 31,041 (fall 2023)[13] |

| Undergraduates | 23,629 (fall 2023)[13] |

| Postgraduates | 7,412 (fall 2023)[13] |

| Location | , , United States 38°56′43″N 92°19′44″W / 38.9453°N 92.3288°W |

| Campus | Midsize city[14], 1,262 acres (511 ha)[6] Total, 19,261 acres (7,795 ha) |

| Newspaper | |

| Colors | Old gold and black[16] |

| Nickname | Tigers |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Truman the Tiger |

| Website | missouri |

| |

The University of Missouri (Mizzou or MU) is a public land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri, United States. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus University of Missouri System. Founded in 1839, MU was the first public university west of the Mississippi River.[17] It has been a member of the Association of American Universities since 1908 and is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity."[18]

Enrolling 31,041 students in 2023, it offers more than 300 degree programs in thirteen major academic divisions.[13][19] Its Missouri School of Journalism, founded by Walter Williams in 1908, was established as the world's first journalism school; it publishes a daily newspaper, the Columbia Missourian, and operates NBC affiliate KOMU.[20][21][22] The University of Missouri Research Reactor Center is the sole source of isotopes in nuclear medicine in the United States.[23] The university operates University of Missouri Health Care, running several hospitals and clinics in Mid-Missouri.

Its NCAA Division I athletic teams are the Missouri Tigers and compete in the Southeastern Conference. The American tradition of homecoming is widely recognized to have originated at MU.[24][25]

History

[edit]

Early years

[edit]In 1839, the Missouri Legislature passed the Geyer Act to establish funds for a state university.[26] It was the first public university west of the Mississippi River.[27] To secure the university, the citizens of Columbia and Boone County pledged $117,921 in cash and land to beat out five other central Missouri counties for the location of the state university.[27] The land on which the university was constructed was just south of Columbia's downtown and owned by James S. Rollins who was later called the "Father of the University."[28] As the first public university in the Louisiana Purchase, the school was shaped by Thomas Jefferson's ideas about public education.[29] The school initially admitted only white male students.[30]

In 1862, the American Civil War forced the university to close for much of the year.[31] Residents of Columbia formed a Union "home guard" militia that became known as the "Fighting Tigers of Columbia". They were given the name for their readiness to protect the city and university. In 1890, the university's newly formed football team took the name the "Tigers" after the Civil War militia.[32]

In 1870, the institution was granted land-grant college status under the Morrill Act of 1862.[29] The act led to the founding of the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy as an offshoot of the main campus in Columbia. It developed as the present-day Missouri University of Science and Technology.[29] In 1888, the Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station opened. This grew to encompass ten centers and research farms around Missouri.[27] By 1890, the university encompassed a normal college (for training of teachers of students through high school), engineering college, arts, and science college, school of agriculture and mechanical arts. school of medicine, and school of law.[31]

1892–present

[edit]

On January 9, 1892, Academic Hall, the institution's central administrative building, burned in a fire that gutted the building, leaving little more standing than six stone Ionic columns.[33] Under the administration of Missouri Governor David R. Francis, the university was rebuilt, with additions that shaped the modern institution.

After the fire, some state residents tried to have the university moved farther west to Sedalia; but Columbia rallied support to keep it. The columns were retained as a symbol of the historic campus. They are surrounded by the Francis Quadrangle, the oldest part of campus. At the quad's southern end is Academic Hall's replacement, Jesse Hall, named for Richard Jesse (the president of the university at the time of the fire). Built in 1895, Jesse Hall holds many administrative offices and Jesse Auditorium. The buildings surrounding the quad were constructed of red brick, leading to this area becoming known as Red Campus. The area was tied together in planned landscaping and walks in 1910 by George Kessler in a City Beautiful design of the grounds.[34]

To the east of the quadrangle, later buildings constructed of white limestone in 1913 and 1914 to accommodate the new academic programs became known as the White Campus. In 1908 the journalism school opened at MU, claiming to be the world's first.[citation needed]

In April 1923, a black janitor was accused of the rape of the daughter of a University of Missouri professor. James T. Scott was abducted from the Boone County Jail by a lynch mob of townsfolk and students and was hanged from a bridge near the campus.[35]

In late 1935, four graduates of Lincoln University—a traditionally black school about 30 miles (48 km) away in Jefferson City—were denied admission to MU's graduate school. One of the students, Lloyd L. Gaines, brought his case to the United States Supreme Court. On December 12, 1938, in a landmark 6–2 decision, the court ordered the State of Missouri to admit Gaines to MU's law school or provide a facility of equal stature. Gaines disappeared in Chicago on March 19, 1939, under suspicious circumstances. The university granted Gaines a posthumous honorary law degree in May 2006.[36] Undergraduate divisions were integrated by court order in 1950 when the university was compelled to admit African Americans to courses that were not offered at Lincoln University.

On June 5, 1935, the university erected a memorial to the Confederate soldiers of Missouri; it was popularly known as Confederate Rock. The monument was removed in 1974.[37]

Following the 2015–16 University of Missouri protests, the chancellor and system president resigned amid racial complaints by students.[38]

Due to the emerging COVID-19 Pandemic, the university canceled classes on March 11, 2020, and resumed teaching in person in August.[39][40]

Campus

[edit]

The campus of the University of Missouri is 1,262-acre (2.0 sq mi; 510.7 ha)[6] just south of Downtown Columbia and is maintained as a botanical garden. The historical campus is centered on Francis Quadrangle, a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and contains several buildings on the register.

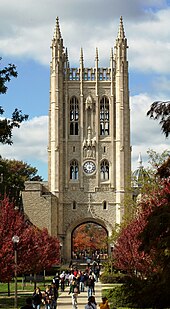

The academic buildings are classified into two main groups: Red Campus and White Campus. Red Campus is the historic core of mostly brick academic buildings around the landmark columns of the Francis Quadrangle; it includes Jesse Hall and Switzler Hall. In the early 20th century, the College of Agriculture received several new buildings. The new buildings, constructed in Neo-Gothic style from native Missouri limestone, form the White Campus. This includes Memorial Union.[41]

During the 1990s, Red Campus was extended to the south with the creation of the Carnahan Quadrangle. Hulston Hall of the University of Missouri School of Law, completed in 1988, formed the eastern border of the future quad. The Reynolds Alumni Center was completed in 1992 on the west side of the new quad. It was completed in 2002 with Cornell Hall of the Trulaske College of Business and Tiger Plaza. Plans for a new plaza on the north end of the Carnahan Quadrangle were unveiled in 2014. Called Traditions Plaza, it was opened on October 25, 2014, during homecoming festivities.[42]

The original MU intercollegiate athletic facilities, such as Rollins Field and Rothwell Gymnasium, were just south of the academic buildings. Expanded facilities were constructed across Stadium Boulevard, where Memorial Stadium opened in 1926. The Hearnes Center was built to the east of the stadium in 1972. In 1994, the university developed the first draft of a master plan for the campus to tie together all of Tiger athletic facilities to the south of Stadium Boulevard and add to its design. The MU Sports Park includes the Mizzou Arena, Taylor Stadium, Walton Stadium, Mizzou Athletics Training Complex, University Field and Devine Pavilion. Student athletic facilities remain in the core area of campus. Rothwell Gymnasium and Brewer Fieldhouse are part of the 283,579-square-foot (26,345.4 m2) Student Recreation Center, which was ranked number one in the nation in 2005 by Sports Illustrated.[43][44]

The main campus of the University of Missouri Hospitals and Clinics is north of the sports complex. It includes the University of Missouri Hospital and Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital. Two of the hospitals, Columbia Regional Hospital and Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, are northeast of the main campus near I-70.

To the south of the MU Sports Park is the MU Research Park. It includes the University of Missouri Research Reactor Center, International Institute for Nano and Molecular Medicine, MU Life Science Business Incubator at Monsanto Place, and Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center. In 2005, the University of Missouri Board of Curators approved legislation to designate the South Farm of the College of Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources (CAFNR) as a research park. The 114-acre (46.1 ha) park, three miles (4.8 km) southeast of the main campus on US63 is Discovery Ridge Research Park. Tenants at Discovery Ridge include ABC Laboratories and the MU Research Animal Diagnostic Laboratory.

The main campus is flanked to the east and west by Greek Life housing. The University of Missouri has nearly 50 national social fraternities and sororities, many of which occupy historical residences valued in the millions of dollars. Beta Sigma Psi, Kappa Alpha Order, Sigma Chi, Beta Theta Pi (originally Zeta Phi), Alpha Gamma Rho, Tau Kappa Epsilon and Sigma Nu form a Greek Row (also called Frat Row) along College Avenue in the East Campus area. Delta Tau Delta, Kappa Sigma, Lambda Chi Alpha, and Sigma Alpha Epsilon are in the West Campus area along Stewart Street, which leads directly into the Francis Quadrangle. Most of the Greek-letter organizations are in a Greek Town, with approximately 30 Greek residences, to the north of Memorial Stadium.

In 2019 a new Center for Missouri Studies was opened as a new headquarters for the State Historical Society of Missouri. In 2020, a new home for the School of Music was finished, the Sinquefield Music Center.

In media

[edit]The campus is the major setting for the 1965 novel Stoner by John Edward Williams. Protagonist William Stoner is an English professor who was raised on a farm in nearby Boonville.[45]

Organization and administration

[edit]| College or school founding[46] | |

|---|---|

| College or school | Year founded |

| College of Arts and Science | 1841 |

| College of Education & Human Development | 1868[47] |

| College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources | 1870[48] |

| School of Law | 1872 |

| School of Medicine | 1872 |

| College of Engineering | 1877 |

| Graduate School | 1896 |

| School of Journalism | 1908 |

| Trulaske College of Business | 1914 |

| School of Music | 1917 |

| Sinclair School of Nursing | 1920 |

| College of Veterinary Medicine | 1946 |

| School of Social Work | 1948 |

| Honors College | 1958 |

| College of Human Environmental Sciences | 1960 |

| School of Accountancy | 1975 |

| School of Natural Resources | 1989[49] |

| School of Information Science & Learning Technologies | 1997[50] |

| College of Health Sciences | 2000 |

| Truman School of Public Affairs | 2001[51] |

| School of Visual Studies | 2018 |

The University of Missouri is organized into seven colleges, and eleven schools and hosts approximately 300 majors.

Name

[edit]Upon creation of the system, each university was renamed with its host city; thus, the university in Columbia became the University of Missouri–Columbia. In the proceeding decades, colloquial and verbal usage of the generic name of MU continued. There were attempts to drop Columbia from its name by students, faculty, alumni, and administrators who said it might cause the university to be perceived as a regional institution. This change was long resisted by the UM System and the other universities based on uniformity and fairness. However, after a renewed effort for "name restoration", the board of curators voted unanimously on November 29, 2007, to allow MU to drop Columbia from its name for all public use.[52] The name University of Missouri–Columbia continues to be advocated by some faculty, administration, and alumni of UMKC, UMSL, and Missouri S&T.[53][54]

Presidents and chancellors

[edit]Each campus of the University of Missouri System is led by a chancellor, who reports to the president of the UM System.[55][56]

Presidents, 1841–1863 and Chancellors, 1963–present

- John Hiram Lathrop (1841–49)

- James Shannon (1850–56)

- William Wilson Hudson (1856–59)

- Benjamin Blake Minor (1860–62)

- John Hiram Lathrop (1865–66)

- Daniel Read (1866–76)

- Samuel Spahr Laws (1876–89)

- Richard Henry Jesse (1891–1908)

- Albert Ross Hill (1908–21)

- John Carleton Jones (1922–23)

- Stratton Brooks (1923–30)

- Walter Williams (1931–35)

- Frederick Middlebush (1935–54)

- Elmer Ellis (1955–63)[a]

- John W. Schwada (1964–70)

- Herbert W. Schooling (1971–78)

- Barbara Uehling (1978–87)

- Haskell Monroe (1987–93)

- Charles Kiesler (1993–96)

- Richard L. Wallace (1997–2004)

- Brady J. Deaton (2004–13)[57]

- R. Bowen Loftin (2014–2015)[58]

- Alexander Cartwright[59] (2017–2020)[60][61][62]

- Mun Choi (2020–present)[b][63]

Academics

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[64] | 116 |

| U.S. News & World Report[65] | 109 (tie) |

| Washington Monthly[66] | 52 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[67] | 180 |

| Global | |

| QS[68] | 641–650 |

| THE[69] | 401–500 |

| U.S. News & World Report[70] | 466 (tie) |

MU is a member of the Association of American Universities and classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[71] The oldest global university ranking project, the Academic Ranking of World Universities (Shanghai Ranking), places MU at 60-78 nationally and 201-300 globally as of 2024. [72] The ranking largely takes into account research output and faculty prestige. In 2024 the university's research and development expenditures were $462 million as submitted to the National Science Foundation. [73] MU is also one of two land-grant universities in the state, along with Lincoln University.

In 1908, the Missouri School of Journalism was founded in Columbia. It has been ranked the top journalism school in the United States several times by the NewsPro–RTDNA survey.[74] Although it claims to be the world's first, the Ecole Supérieure de Journalisme de Paris was established in 1899.

The UM System owns and operates KOMU-TV, the NBC/CW affiliate for Columbia and nearby Jefferson City. It is a full-fledged commercial station and a working lab for journalism students. The MU School of Journalism publishes the Columbia Missourian and Vox Magazine where students learn reporting, editing, and design in a newsroom managed by professional editors. It operates the local National Public Radio Station KBIA and produces Radio Adelante, a Spanish-language radio program.

Founded in 1978 after 23 years as a unit of the School of Medicine, the School of Health Professions became an autonomous division in December 2000. It is Missouri's only state-supported school of health professions on a campus with an academic health center, and the only allied health school in the UM system.[75]

The university maintains the largest library collection in the State of Missouri. In the 2011–12 academic year, it held 3.1 million volumes, 8.1 million microforms, 678,596 e-books, almost 1.7 million government documents, more than 284,000 print maps, and more than 53,000 journal subscriptions.[6][76] The collection is housed in Ellis Library, the University Archives, and seven other specialized academic libraries across campus.[6][77]

During the American Civil War, Union troops used the library in Academic Hall as a guard room. They caused significant damage, including taking 467 volumes to build fires. The board of curators later sued the US Army for the destruction on campus. Settled in 1915, the suit's award was used to build the Memorial Gateway on the northern edge of Red Campus.[78]

In 1913, construction began on a new main library, completed in 1915. It was expanded in 1935, 1958, and 1985. It was dedicated as Elmer Ellis Library on October 10, 1972, in honor of the thirteenth president of the University of Missouri. The MU libraries are home to the 47th largest research collection in North America.[79]

MU merged two departments, the Center for Distance and Independent Study and MU Direct: Continuing and Distance Education, to form Mizzou Online in 2011.[80][81] Mizzou Online offers online courses for 18 of the university's colleges[80] and operates the University of Missouri High School, a distance learning K-12 high school.[82] In the U.S. News & World Report’s 2024 Best Online Programs, MU ranks 28th in the best online bachelor’s degree programs out of 339 universities nationwide.[83]

Admissions

[edit]MU is the largest public university in Missouri. Of those applying for freshman admission, 78.1% are admitted with those matriculating having an average GPA of 3.6, an average SAT composite score of 1232 out of a maximum of 1600, and an average ACT composite score of 26 out of a maximum of 36.[84]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[85] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 78% | ||

| Black | 7% | ||

| Hispanic | 5% | ||

| Other[c] | 5% | ||

| Asian | 3% | ||

| Foreign national | 1% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[d] | 25% | ||

| Affluent[e] | 75% | ||

| Age [86] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age | 20 | ||

| undergrads 25 and older | 3% | ||

| State of residence (excluding foreign national students) | |||

| In state | 80% | ||

| Out of state | 20% | ||

Residential life

[edit]The University of Missouri operates 23 on-campus residence halls and at least two other off-campus sites. The two off-campus locations include Tiger Diggs at Campus View Apartments and True Scholars House.

Groups and activities

[edit]Tap Day is an annual spring ceremony in which the identities of the members of the six secret honor societies are revealed. The participating societies are QEBH, Mystical Seven, LSV, Omicron Delta Kappa, Mortar Board, and the Rollins Society. The ceremony, first held in 1927, takes place at the columns on Francis Quadrangle.

The Trulaske Consulting Association was started in 2009.[87] It is open to students of all departments. However, most members are MBA and undergrad business students. The association aims to increase awareness, provide exposure, and facilitate networking between students and professionals in the consulting industry.[88] The growing popularity of the association has been attributed to the resources available to student members. Workshops by management consultants and case studies on strategy form an integral part of the activities organized by TCA.[89]

The Muslim Student Organisation (MSO) is for the Muslims at the University of Missouri-Columbia.[90][91]

The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute explores the modern significance of the Ten Commandments.[92][93][94][95]

Greek life

[edit]Founded in 1869, the Greek Community represents 22% of the student population. More than 70 Greek-letter organizations are active at MU.[verification needed][96][97]

Homecoming

[edit]

In 1911, athletic director Chester Brewer invited alumni to "come home" for the big football game against the University of Kansas. A spirit rally and parade were planned as part of the celebration. Missouri Homecoming also includes several service elements, and the homecoming blood drive has earned the Guinness Record as the nation's largest.[98]

Athletics

[edit]

The Missouri Tigers are a member of the Southeastern Conference except wrestling, which competes in the Big 12 Conference. Mizzou is the only school in the state with all of its sports in the NCAA Division I and a football team that competes in the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS). These are the highest levels of college sports in the United States. Their official colors are black and gold.

Athletic sports for the Tigers include men's and women's basketball, baseball, cross country, football, golf, gymnastics, swimming & diving, softball, track, tennis, volleyball, women's soccer, and wrestling. Historic sports included a shooting club, in which the ladies' team in 1934 won a national championship.

MU football games are on Faurot Field at Memorial Stadium ("The Zou"). Built in 1926, this stadium has an official capacity of 71,168,[99] and features a nearly 100 ft (30 m) wide "M" behind the north-end zone. Men's and women's basketball games take place at the Mizzou Arena, just south of the football stadium. The Hearnes Center hosted men's and women's basketball from 1972 to 2004 and it is still used for other athletic (including wrestling, volleyball, and indoor track and field) and school events.

The Missouri Tiger men's basketball team has had 29 NCAA Tournament appearances, the second-most Tournament appearances without a Final Four. The Tigers have appeared in the regional finals (Elite Eight) of the NCAA Tournament six times (twice under coach Norm Stewart, Missouri head coach from 1967 to 1999). The Tigers have won 15 conference championships, beginning with the Missouri Valley Conference, followed by the Big Six, the Big Eight, and the Big 12 Conference. In 1994, the Tigers went undefeated in the Big Eight to take the regular season title. In 2009, Missouri won its first Big 12 Championship[101] over Baylor. Missouri went on to win its second Big 12 Championship in its final season in the Big 12 in 2012, once again defeating Baylor. Standout players from the Mizzou's basketball team include Anthony Peeler, John Brown, Jon Sundvold, Steve Stipanovich, Kareem Rush, Keyon Dooling Doug Smith, Willie Smith, Norm Stewart, Linas Kleiza, Derrick Chievous, DeMarre Carroll, Kim English, Jordan Clarkson, and Marcus Denmon.

The official mascot for Missouri Tigers athletics is Truman the Tiger, created on September 16, 1986. Following a campus-wide contest, Truman was named in honor of Harry S. Truman, the only U.S. president from Missouri. Truman appears to cheer on the team, mingle with athletic supporters, visit alumni association functions, and visit Columbia-area schools.

On November 6, 2011, the University of Missouri announced it would leave the Big 12 Conference to join the Southeastern Conference effective July 1, 2012.[102] In September 2012, the school's wrestling team became an associate member of the Mid-American Conference, as the SEC does not sponsor wrestling.

Student outcomes

[edit]According to College Scorecard, the median income in 2020 and 2021 for graduates who matriculated in 2010 and 2011 was $63,403, with 82% of graduates making more than high school graduates.[103]

The Center on Education and the Workforce estimated that the return on investment with a bachelors at Mizzou is $101,000 10 years after graduation, this accelerates to $1,006,000 40 years after graduation.[104]

Graduation rates

[edit]According to College Scorecard, the graduation rate at Mizzou is 72%.[103]

Notable people

[edit]In 2016, there were 300,315 living alumni worldwide. Of those, 274,447 resided in the United States, 156,585 in Missouri, 61,346 in the St. Louis metropolitan area, 30,018 in the Kansas City metropolitan area, and 2,718 outside the U.S.[105] Other alumni, faculty, and staff include 18 Rhodes Scholars,[106] 19 Truman Scholars,[107] 150 Fulbright Scholars,[108] 7 Governors of Missouri,[109] and 6 members of the U.S. Congress.[110] Two alumni and faculty have been awarded the Nobel Prize: alumnus Frederick Chapman Robbins won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1954[111] and George Smith was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018 while affiliated with the university.[112]

- William F. Baker, engineer of Burj Khalifa

- Tom Berenger, Emmy Award-winning actor

- Emily Newell Blair, writer, suffragist, and founder of League of Women Voters

- Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, writer and TV producer

- Andy Bryant, chairman of Intel Corporation

- Kate Capshaw, actor, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

- Michael Chandler, three-time Bellator Lightweight Champion and UFC fighter

- Marcia Chatelain, 2021 Pulitzer Prize for History winner

- Peggy Cherng, co-founder of Panda Express

- Chris Cooper, Academy Award-winning actor

- Sheryl Crow, musician

- Robert K. Dixon, Nobel laureate, presidential adviser, and scientist

- Linda M. Godwin, NASA astronaut

- Jim Fitterling, Chairman and CEO, Dow

- Jon Hamm, actor, Don Draper of Mad Men

- William Least Heat-Moon, author, Blue Highways

- Martin Heinrich, United States Senator for New Mexico

- Edward D. "Ted" Jones, managing partner of Edward Jones Investments

- Tim Kaine, 2016 vice-presidential nominee and senator for Virginia

- Ian Kinsler, four-time MLB All-Star

- Kenneth Lay, founder, chairman, and CEO of Enron Corporation and convicted felon for securities fraud

- Jim Lehrer, journalist, PBS NewsHour

- Robert Loggia, actor

- Richard Matheson, author, I Am Legend, The Shrinking Man

- Claire McCaskill, U.S. Senator (2007–19); Political Analyst - NBC

- Barbara McClintock, cytogeneticist, winner of Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Russ Mitchell, journalist, CBS

- William W. Mayo, founder of Mayo Clinic

- Cleo A. Noel Jr., former ambassador to Sudan

- Brad Pitt, actor and film producer

- Max Scherzer, eight-time MLB All-Star and three-time Cy Young Award winner

- George C. Scott, Academy Award-winning actor, Dr. Strangelove, Patton

- Mike Shannon, MLB player, St. Louis Cardinals radio broadcaster

- Ram Subhag Singh, Indian politician, freedom fighter

- Debbye Turner (Bell), TV personality, Miss America 1990

- Mort Walker, cartoonist (Beetle Bailey, Hi and Lois)

- Sam Walton, founder of Walmart

- Tennessee Williams, playwright, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, A Streetcar Named Desire

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ellis became president of the University of Missouri System upon its creation, serving until 1966.

- ^ Choi is the first Chancellor to simultaneously be President of the University of Missouri System.

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans and those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ "Search". Internet Archive.

- ^ Switzler, William F. (1882). History of Boone County. St. Louis, Missouri: Western Historical Company. p. 327. OCLC 2881554.

- ^ "Our History". University of Missouri System. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "UM Seal Guidelines and History". Curators of the University of Missouri. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "University of Missouri System Style Guide" (PDF). Curators of the University of Missouri. September 7, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "MU Endowment Pool Profile". University of Missouri. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "Quarterly Performance Report" (PDF). University of Missouri System. October 2, 2023. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 3, 2023. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "U.S. and Canadian 2023 NCSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2023 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY22 to FY23, and FY23 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student" (XLSX). National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO). February 15, 2024. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ "Operating Budget" (PDF). University of Missouri System. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Mara Jose (July 28, 2020). "President of 4 universities now also head of Mizzou. Faculty at other schools worry". Kansas City Star. Kansas City, Missouri. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "Matthew Martens, Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs". provost.missouri.edu. 2024. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ a b "Student Enrollment (Employee Headcount tab)". University of Missouri. 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Student Enrollment // MU Analytics". muanalytics.missouri.edu. 2014–2023. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "College Navigator - University of Missouri-Columbia". nces.ed.gov.

- ^ "HLC-University of Missouri".

- ^ Mizzou Athletics Brand Identity Guidelines (PDF). July 9, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- ^ "University of Missouri". Britannica Kids. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Carnegie R1 and R2 Research Classifications Doctoral Universities (updated 2018)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Colleges & Schools | University of Missouri". missouri.edu. 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "World's First J-School Celebrates 100 Years". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Colleges and Schools". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "KOMU Celebrates 50 Years of News Coverage and Community Service". Missouri School of Journalism. February 9, 2004. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Williams, J. E. (June 1998). "MURR- The World's Most Powerful University Research Reactor". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 39 (6): 13N–26N. ISSN 0161-5505. PMID 9627317.

- ^ "The first homecoming: Missouri helped invent a college football tradition - Saturday Down South". www.saturdaydownsouth.com. April 8, 2015.

- ^ Brooke, Eliza (August 31, 2015). "The History of Homecoming". Vice: Broadly. Vice Magazine. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ "History of the Board of Curators". Archives of the University of Missouri. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c "History of the University of Missouri-Columbia". Office of Web Communications. Retrieved November 19, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Founding father descendant establishes slavery atonement endowment". University Development. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c "History of the University". Curators of the University of Missouri. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ Gutierrez, Lisa (November 13, 2015). "The history of black students' fight for equality at the University of Missouri". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "Significant Dates in the History of the University of Missouri". University Archives. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "The Border War Rages On". Missouri Civil War Museum. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "History of the Columns". University of Missouri Office of Web Communications. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Missouri - George Kessler". georgekessler.org. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ^ Mytelka, Andrew (November 9, 2010). "Local Leaders Mark 1923 Lynching of U. of Missouri Janitor". Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018.

- ^ Zagier, Alan Scher (May 14, 2006). "MU awards law degree to kin of rights pioneer". Columbia Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2006.

- ^ "Confederate Rock". MU in Brick and Mortar. University of Missouri. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ Viviani, Nick (November 9, 2015). "University of Missouri Chancellor Follows President in Stepping Down". WIBW-TV. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Columbia Daily Tribune". www.columbiatribune.com. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

- ^ Staff, KMBC 9 News (June 10, 2020). "After COVID-19 shutdown, Mizzou to resume in-person classes for fall 2020 semester". KMBC. Retrieved July 28, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Fischer, William (April 24, 2022). "Memorial Union Tower".

- ^ "Traditions Plaza". Mizzou Alumni Association. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ "Case Study: University of Missouri-Columbia Student Recreation Center" (PDF). Colotime.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Lewis, Megan (February 17, 2012). "Rec Center Receives National Attention". The Maneater. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Julian (December 13, 2013). "Stoner: the must-read novel of 2013". The Guardian. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ "Significant Dates in the History of the University of Missouri". Archives of the University of Missouri. February 16, 2005. Retrieved November 8, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Educating Missouri for 140 Years and Going Strong – College of Education | University of Missouri". Education.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "History of the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources | Mizzou – University of Missouri". Missouri.edu. October 29, 2009. Archived from the original on September 3, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "SNR: A Brief History". Snr.missouri.edu. October 30, 2006. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "School of Information Science & Learning Technologies – College of Education | University of Missouri". Education.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Harry S Truman School of Public Affairs | About the Truman School of Public Affairs". Truman.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "UM Curators recognize historic status of MU". Missouri.edu. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ "MU name deal ruffles some feathers". Columbia Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ Njus, Elliot (September 21, 2007). "UMSL Opposes MU Name Change". The Maneater. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ "University of Missouri Leaders". Muarchives.missouri.edu. September 10, 2002. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ "Former presidents of the University of Missouri". Archived from the original on August 19, 2007.

- ^ "Chancellor Announces Retirement". University of Missouri ("Mizzou News"). June 12, 2013. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Loftin Leadership: Outgoing Texas A&M president becomes Mizzou's new chancellor". University of Missouri. December 5, 2013. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- ^ "Office of the Chancellor: Dr. Alexander N. Cartwright, Chancellor-designate". University of Missouri. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ "Cartwright for the Job". University of Missouri. May 24, 2017. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ "Made for Mizzou". University of Missouri. May 24, 2017. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Mara Rose (March 20, 2020). "University of Missouri chancellor leaving after 3 years to lead a Florida college". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020.

- ^ "UM Board of Curators appoints Choi interim chancellor at MU". The Curators of the University of Missouri. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ https://www.shanghairanking.com/institution/university-of-missouri-columbia

- ^ https://showme.missouri.edu/2024/mu-secures-record-research-spending-capping-10-consecutive-years-of-growth/

- ^ "Missouri School of Journalism Voted No. 1 in Annual NewsPro-RTDNA Poll – Missouri School of Journalism". December 22, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "History of the School of Health Professions". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Facts about the Libraries". Mulibraries.missouri.edu. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ "MU Libraries and Collections". MU Libraries. June 3, 2013. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ "The Heart of the University: MU Libraries". Muarchives.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ "JLib affiliated libraries". Mulibraries.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "About Mizzou Online". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Yaeger, Katie (September 2, 2011). "CDIS and MU Direct merge to form Mizzou Online". The Maneater. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ "Online Degrees and Programs". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ "Leading the pack: MU named among the best online bachelor's programs in the nation". showme.missouri.edu. February 7, 2024.

- ^ "University of Missouri - Columbia Requirements for Admission". prepscholar.com. PrepScholar. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of Missouri-Columbia". United States Department of Education. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "University of Missouri Common Data Set 2023-2024".

- ^ Trambu, Aamer. "About us page". TCA. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Trambu, Aamer. "About us page". spartymantz. TCA. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Schult, Michael. "Upcoming Events". spartymantz. TCA. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ "About Us page". About Us. Muslim Student Organisation – Mizzou Chapter. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Bates, Bari (October 28, 2011). "Speaker brings an understanding of Islamic law, humor to a presentation at MU". Columbia Missourian. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ^ Danielsen, Aarik (November 22, 2014). "Feeling at home: Rabbi encourages students to discover joy in life, Judaism". Columbia Daily Tribune.

- ^ Hudson, Repps (November 23, 2011). "Chabad opens student center at Mizzou". The Jewish Light. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Newman, Zack (April 17, 2015). "Mid-Missouri Jewish community gathers after anti-semitism". KOMU 8. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Kerfin, Caitlin (December 17, 2014). "Missouri celebrates the first night of Hanukkah". Columbia Faith and Values. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ "MU Engage". May 23, 2022. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Interfraternity Council". Fraternity & Sorority Life. December 11, 2023.

- ^ "Red Cross Campus Connections" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ "University of Missouri Athletics". Mutigers.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ National Archieff, the Netherlands

- ^ "All-Time Big 12 Championships – Big 12 Conference – Official Athletic Site". Big12sports.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Associated Press (November 12, 2011). "Missouri to SEC Ignites a War of Words". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ a b "College Scorecard". collegescorecard.ed.gov. Retrieved November 30, 2024.

- ^ "A First Try at ROI: Ranking 4,500 Colleges". CEW Georgetown. Retrieved November 30, 2024.

- ^ "Mizzou". Missouri Alumni Association. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Rhodes Scholarships Number of Winners by Institution U.S. Rhodes Scholars 1904 – 2020" (PDF).

- ^ "Scholar Listing". The Harry S. Truman Scholarship Foundation. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Grantee Directory". us.fulbrightonline.org. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Missouri". National Governors Association. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Mizzou". Mizzou. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1954". NobelPrize.org. Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Notable Alumni". missouri.edu. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Budds, Michael (2018). 100 Years of Music-Making at Mizzou. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri School of Music. ISBN 9780692987322.

- Dains, Mary K. "University of Missouri Football: The First Decade." Missouri Historical Review 70 (October 1975): 20-54. online

- Dearmont, W. S. "The Building of the University of Missouri, an Epoch Making Step." Missouri Historical Review 25 (January 1931): 240-244. online

- Ellis, Elmer (1989). My Road to Emeritus. Columbia, Missouri: State Historical Society of Missouri. ISBN 0962289116.

- Olsen, James and Vera (1988). The University of Missouri An Illustrated History. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826206787.

- Quarles, James Thomas (1924). University of Missouri Songs (1 ed.). Columbia, Missouri: Curators of the University of Missouri. OCLC 19229550.

- Stephens, Frank Fletcher (1962). A History of the University of Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9781258386566.

- Viles, Jonas. The University of Missouri, 1839–1939 , E.W. Stephens Publishing Company

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Official website of University of Missouri Athletics

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . . 1914.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- University of Missouri

- Land-grant universities and colleges

- Educational institutions established in 1839

- Universities and colleges established in the 1830s

- 1839 establishments in Missouri

- Universities and colleges in Columbia, Missouri

- Forestry education

- Flagship universities in the United States

- Public universities and colleges in Missouri