On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

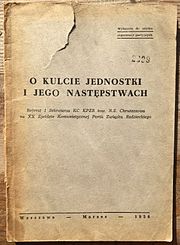

On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences (Russian: «О культе личности и его последствиях», romanized: “O kul'te lichnosti i yego posledstviyakh”), popularly known as the Secret Speech (Russian: секретный доклад Хрущёва, romanized: sekretnïy doklad Khrushcheva), was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 February 1956.[1] Khrushchev's speech was sharply critical of the rule of the deceased General Secretary and Premier Joseph Stalin, particularly with respect to the purges which had especially marked the last years of the 1930s. Khrushchev charged Stalin with having fostered a leadership cult of personality despite ostensibly maintaining support for the ideals of communism. The speech was leaked to the West by the Israeli intelligence agency Shin Bet, which received it from the Polish-Jewish journalist Wiktor Grajewski.

The speech was shocking in its day.[2] There are reports that some of those present suffered heart attacks and that the speech even inspired suicides, due to the shock with all of Khrushchev's accusations and defamations against the government and the figure of Stalin.[3][failed verification] The ensuing confusion among many Soviet citizens, raised on panegyrics and permanent praise of the "genius" of Stalin, was especially apparent in Georgia, Stalin's homeland, where days of protests and rioting ended with a Soviet army crackdown on 9 March 1956.[4] In the West, the speech politically devastated organised communists; the Communist Party USA alone lost more than 30,000 members within weeks of its publication.[5]

The speech was cited as a major cause of the Sino-Soviet split by China (under Chairman Mao Zedong) and Albania (under First Secretary Enver Hoxha), who condemned Khrushchev as a revisionist. In response, they formed the anti-revisionist movement, criticizing the post-Stalin leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for allegedly deviating from the path of Lenin and Stalin.[6] In North Korea, factions of the Workers' Party of Korea attempted to remove Chairman Kim Il Sung, criticizing him for not "correcting" his leadership methods, developing a personality cult, distorting the "Leninist principle of collective leadership" and "distortions of socialist legality"[7] (i.e. using arbitrary arrest and executions) and using other Khrushchev-era criticisms of Stalinism against Kim Il Sung's leadership.

Background

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Former First Secretary of the CPSU Domestic policy

Foreign policy

Catchphrases and incidents Media gallery |

||

The issue of mass repressions was known to Soviet leaders well before the speech. The speech itself was prepared based on the results of a special party commission (chairman Pyotr Pospelov, P. T. Komarov, Averky Aristov, and Nikolai Shvernik), known as the Pospelov Commission, arranged at the session of the Presidium of the Party Central Committee on 31 January 1955. The direct goal of the commission was to investigate the repressions of the delegates of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in 1934.

The 17th Congress was selected for investigations because it was known as "the Congress of Victors" in the country of "victorious socialism" and so the enormous number of "enemies" among the participants demanded explanation. The commission presented evidence that in 1937 and 1938 (the peak of the period known as the Great Purge), over one-and-a-half million individuals, the majority being long-time CPSU members, were arrested for "anti-Soviet activities", of whom over 680,500 were executed.[8]

Speech

[edit]The public session of the 20th Congress had come to a formal end on 24 February 1956, when word was spread to delegates to return to the Great Hall of the Kremlin for an additional "closed session" to which journalists, guests and delegates from "fraternal parties" from outside the Soviet Union were not invited.[9] Special passes were issued to those eligible to participate, with an additional 100 former party members, who had been recently released from the Soviet prison camp network, added to the assembly to add moral effect.[9]

Premier Nikolai Bulganin, chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union and then an ally of Khrushchev, called the session to order and immediately yielded the floor to Khrushchev,[9] who began his speech shortly after midnight on 25 February. For the next four hours, Khrushchev delivered "On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" before stunned delegates.[9] Several people became ill during the tense report and had to be removed from the hall.[9]

Khrushchev read from a prepared report, and no stenographic record of the closed session was kept.[10] No questions or debate followed Khrushchev's presentation and delegates left the hall in a state of acute disorientation.[10] The same evening, the delegates of foreign communist parties were called to the Kremlin and given the opportunity to read the prepared text of the Khrushchev speech, which was treated as a top secret state document.[10]

On 1 March, the text of the Khrushchev speech was distributed in printed form to senior Central Committee functionaries.[11] That was followed, on 5 March, by a reduction of the document's secrecy classification from "Top Secret" to "Not for Publication".[12] The Party Central Committee ordered that Khrushchev's Report be read at all gatherings of Communist and Komsomol local units, with non-party activists invited to attend the proceedings.[12] Therefore, the "Secret Speech" was read publicly at thousands of meetings, making the colloquial name of the document something of a misnomer.[12] The full text was officially published in the Soviet press in 1989.[13]

Reporting

[edit]

Shortly after the conclusion of the speech, reports of its delivery, and its general content, were conveyed to the West by Reuters journalist John Rettie, after a Soviet acquaintance briefed him about the speech a few hours before Rettie left for Stockholm on holiday. It was therefore reported in Western media in early March. Rettie came to believe the information came from Khrushchev himself, via the intermediary.[14]

The content of the speech reached the West through a circuitous route. A few copies of the speech were sent by order of the Soviet Politburo to leaders of the Eastern Bloc countries. Shortly after the speech had been disseminated, a Polish-Jewish journalist, Wiktor Grajewski, visited his girlfriend, Łucja Baranowska, who worked as a junior secretary in the office of the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party, Edward Ochab. On her desk was a thick booklet with a red binding, with the words: "The 20th Party Congress, the speech of Comrade Khrushchev". Grajewski had heard rumours of the speech and, as a journalist, was interested in reading it. Baranowska allowed him to take the document home to read.[15][16]

As it happened, Grajewski had made a recent trip to Israel to visit his sick father, and resolved to emigrate there. After he read the speech, he decided to take it to the Israeli embassy, and gave it to Yaakov Barmor, who had helped Grajewski undertake his trip. Barmor, a Shin Bet representative, took photographs of the document and sent them to Israel.[15][16][17]

By the afternoon of 13 April 1956, the Shin Bet in Israel had received the photographs. Israeli intelligence and United States intelligence had secretly agreed previously to co-operate on security matters. The photographs were delivered to James Jesus Angleton, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) head of counterintelligence, and in charge of the clandestine liaison with Israeli intelligence. On 17 April 1956, they reached the CIA chief, Allen Dulles, who quickly informed US President Dwight D. Eisenhower. After determining that the speech was authentic, the CIA leaked the speech to The New York Times in early June.[16]

"...the speech, never published in the U.S.S.R., was of great importance for the Free World. Eventually the text was found – but many miles from Moscow, where it had been delivered. ... I have always viewed this as one of the major coups of my tour of duty in intelligence."

— Allen Dulles[18]

Summary

[edit]While Khrushchev was not hesitant to point out the flaws in Stalinist practice in regard to the purges of the army and party and the management of the Great Patriotic War, the Soviet Union's involvement in World War II, he was very careful to avoid any criticism of Stalin's industrialization policy or party ideology. Khrushchev was a staunch party man and lauded Leninism and communist ideology in his speech as often as he condemned Stalin's actions. Stalin, Khrushchev argued, was the primary victim of the deleterious effect of the cult of personality,[19] which, through his existing flaws, had transformed him from a crucial part of the victories of Lenin into a paranoiac man who was easily influenced by the "rabid enemy of our party", Lavrentiy Beria.[20]

The basic structure of the speech was as follows:

- Repudiation of Stalin's cult of personality.

- Quotations from the classics of Marxism–Leninism which denounced the "cult of an individual", especially the Karl Marx letter to a German worker that stated his antipathy toward it.

- Lenin's Testament and remarks by Nadezhda Krupskaya (former People's Commissar for Education and wife of Lenin), about Stalin's character.

- Before Stalin, the fight with Trotskyism was purely ideological; Stalin introduced the notion of the "enemy of the people" to be used as "heavy artillery" from the late 1920s.

- Stalin violated the party norms of collective leadership.

- Repression of the majority of Old Bolsheviks and delegates of the 17th Congress, most of whom were workers and had joined the party before 1920. Of the 1,966 delegates, 1,108 were declared "counter-revolutionaries"; 848 were executed, and 98 of 139 members and candidates to the Central Committee were declared "enemies of the people".

- After the repression, Stalin ceased even to consider the opinion of the collective of the party.

- Examples of repression of some notable Bolsheviks were presented in detail.

- Stalin's order for the persecution to be enhanced: the NKVD was "four years late" in crushing the opposition, according to his principle of "aggravation of class struggle".

- Practice of falsifications followed to cope with "plans" for numbers of enemies to be uncovered.

- Exaggerations of Stalin's role in the Great Patriotic War (World War II).

- Deportations of whole nationalities.

- Doctors' plot and Mingrelian affair.

- Manifestations of personality cult: songs, city names and so on.

- Lyrics of the State Anthem of the Soviet Union (first version, 1944–1953), which had references to Stalin.

- The non-awarding of the Lenin State Prize since 1935, which should be corrected at once by the Supreme Soviet and the Council of Ministers.

- Repudiating the socialist realist literary policy under Stalin, also known as Zhdanovism, which affected literary works.

Influence

[edit]On 30 June 1956, the Central Committee of the party issued a resolution, "On Overcoming the Cult of the Individual and Its Consequences",[21] which served as the party's official and public pronouncement on the Stalin era. Written under the guidance of Mikhail Suslov, it did not mention Khrushchev's specific allegations. "Complaining that Western political circles were exploiting the revelation of Stalin's crimes, the resolution paid tribute to [Stalin's] services" and was relatively guarded in its criticisms of him.[22]

Khrushchev's speech was followed by a period of liberalization, known as the Khrushchev Thaw, into the early 1960s. In 1961, the body of Stalin was removed from public view in Lenin's mausoleum and buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.

Criticism

[edit]Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski criticized Khrushchev in 1978 for failing to make any analysis of the system Stalin presided over, stating:

Stalin had simply been a criminal and a maniac, personally to blame for all the nation's defeats and misfortunes. As to how, and in what social conditions, a bloodthirsty paranoiac could for twenty-five years exercise unlimited despotic power over a country of two hundred million inhabitants, which throughout that period had been blessed with the [allegedly] most progressive and democratic system of government in human history—to this enigma the speech offered no clue whatever. All that was certain was that the Soviet system and the party itself remained impeccably pure and bore no responsibility for the tyrant's atrocities.[23]

Bangladeshi historian A. M. Amzad commented on the speech:

It (the speech) was an undesirable, uncalled for and irresponsible act in terms of the ideology of the Soviet Union. It was designed to determine Khrushchev's political fate. Even before the Twentieth Congress, arrangements were made to resolve the ills of Stalin's dictatorship. Thus, such criticism of Stalin at the Twentieth Congress was deliberate.[24]

Western historians also tended to take a somewhat critical view of the speech. J. Arch Getty commented in 1985 that "Khrushchev's revelations [...] are almost entirely self-serving. It is hard to avoid the impression that the revelations had political purposes in Khrushchev's struggle with Molotov, Malenkov, and Kaganovich".[25] The historian Geoffrey Roberts said Khrushchev's speech became "one of the key texts of western historiography of the Stalin era. But many western historians were sceptical about Khrushchev's efforts to lay all the blame for past communist crimes on Stalin".[26]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Translation. Khrushchev, Nikita. "February 25, 1956. Khrushchev's Secret Speech, 'On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,' Delivered at the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union". digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org. The Wilson Center. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Clines, Francis X. (6 April 1989). "Soviets, After 33 Years, Publish Khrushchev's Anti-Stalin Speech". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ From Our Own Correspondent. BBC Radio 4. 22 January 2009.

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny, The Making of the Georgian Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994; pp. 303–305.

- ^ Vivian Gornick (29 April 2017). "When Communism Inspired Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "1964: On Khrushchov's Phoney Communism and Its Historical Lessons for the World". marxists.org.

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (2007). Crisis in North Korea: The Failure of De-Stalinization, 1956. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3207-0.

- ^ William Taubman: Khrushchev: The Man and His Era; 2003; Chapter 11.

- ^ a b c d e Roy Medvedev and Zhores Medvedev, The Unknown Stalin: His Life, Death, and Legacy. Ellen Dahrendorf, trans. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press, 2004, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Medvedev and Medvedev, The Unknown Stalin, p. 103.

- ^ Medvedev and Medvedev, The Unknown Stalin, p. 103–104.

- ^ a b c Medvedev and Medvedev, The Unknown Stalin, p. 104.

- ^ The text was published in the magazine Известия ЦК КПСС (Izvestiya CK KPSS; Reports of the Central Committee of the Party), #3, March 1989.

- ^ Rettie, John (18 February 2006). "The day Khrushchev denounced Stalin". BBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ a b "יש איזשהו נאום של חרושצ'וב מהוועידה". הארץ.

- ^ a b c Melman, Yossi. "Trade secrets", Haaretz, 2006.

- ^ Matitiahu Mayzel (2003). "Israeli Intelligence and the leakage of Khrushchev's "Secret Speech"". Journal of Israeli History. 32 (2): 257–283. doi:10.1080/13531042.2013.822730. S2CID 143346034.

- ^ Allen Dulles: The Craft of Intelligence; 1963; p. 80.

- ^ Chamberlain, William Henry. "Khrushchev's War with Stalin's Ghost", Russian Review 21, #1, 1962.

- ^ Khrushchev, Nikita S. "The Secret Speech – On the Cult of Personality", Fordham University Modern History Sourcebook. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- ^ On Overcoming the Cult of the Individual and Its Consequences. Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

- ^ McClellan, Woodford. Russia: A History of the Soviet Period. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. 1990. p. 239.

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek. Main Currents of Marxism: Its Origin, Growth, and Dissolution Vol. III. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1978. pp. 451–452.

- ^ Amzad, A. M. (Bengali). Sobhiyeta Uniyanera Itihasa: 1917–1991 [History of the Soviet Union: 1917–1991]. Dhaka: Abishkar, 2019. p. 315.

- ^ Getty, J. Arch. Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party Reconsidered, 1933–1938. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985. p. 217.

- ^ Roberts, Geoffrey. Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. London: Yale University Press. 2006. pp. 3–4.

Further reading

[edit]- Hornsby, R. (2023). The Soviet Sixties. Yale University Press.

External links

[edit]- Complete text of the speech (in English) in a contemporary pamphlet, with the original commentary by Nicolaevsky.

- The Anti-Stalin Campaign and International Communism: A Selection of Documents, a 1956 book (published by the Columbia University Press) containing the text of the speech as well as reactions to it from the communist parties of the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy

- Complete text of the speech (in Russian) in a contemporary pamphlet.

- "Khrushchev's speech struck a blow at the totalitarian system" – Mikhail Gorbachev's commentary on the Secret Speech from The Guardian's supplement.

- A Stalinist rebuttal of Khrushchev's "Secret Speech", 1956.

- The day Khrushchev denounced Stalin: former Reuters correspondent John Rettie recounts how he reported Khrushchev's speech to the world.

- 1956 in international relations

- 1956 in the Soviet Union

- 1956 speeches

- Cold War speeches

- Cults of personality

- De-Stalinization

- Documents of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- February 1956 events in Europe

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Shin Bet

- Speeches by Nikita Khrushchev

- Works about Joseph Stalin