Iliupersis

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

| Trojan War |

|---|

|

The Iliupersis (Greek: Ἰλίου πέρσις, Ilíou pérsis, lit. 'Sack of Ilium'), also known as The Sack of Troy, is a lost epic of ancient Greek literature. It was one of the Epic Cycle, that is, the Trojan cycle, which told the entire history of the Trojan War in epic verse. The story of the Iliou persis comes chronologically after that of the Little Iliad, and is followed by the Nostoi ("Returns"). The Iliou persis was sometimes attributed by ancient writers to Arctinus of Miletus who lived in the 8th century BCE (see Cyclic Poets). The poem comprised two books of verse in dactylic hexameter.

Date

[edit]The Iliou persis was probably composed in the seventh century BCE, but there is much uncertainty. Ancient sources date Arctinus to the eighth century BCE, but evidence concerning another of his poems, the Aethiopis, suggests that he lived considerably later than that.

Content

[edit]Only ten lines of the original text of the Iliou persis survive. For its storyline, we are almost entirely dependent on a summary of the Cyclic epics contained in the Chrestomathy written by an unknown Proclus (possibly to be identified with the 2nd century CE grammarian Eutychius Proclus). A few other references give indications of the poem's storyline. A further impression of the poem's content may be gained from book 2 of Virgil's Aeneid (written many centuries after the Iliou persis), which tells the story from a Trojan point of view.

Note that different sources record some details differently: for example the manner of Aeneas' departure from Troy, or the identity of Astyanax's killer. The version told here specifically follows what is known of the early epic poem, rather than any other source.

The poem opens with the Trojans discussing what to do with the wooden horse which the Greeks have left behind: some thought they ought to hurl it down from the rocks, others to burn it up, while others say they ought to dedicate it to Athena. The third opinion prevails, and the Trojans celebrate their apparent victory. The god Poseidon, meanwhile, sends an ill omen of two snakes that kill Laocoön and one of his two sons; seeing this, Aeneas and his men leave Troy in anticipation of what is to come.

When night comes, signaled by Sinon, the Greek warriors inside the horse emerge and open the city gates to let in the Greek army, having sailed back from Tenedos. The Trojans are massacred, and the Greeks set fire to the city.

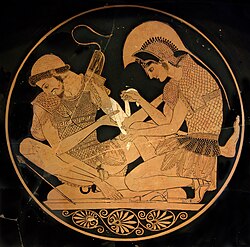

Neoptolemus kills king Priam, even though he has taken refuge at the altar of Zeus; Menelaus kills Deiphobus and takes back his wife Helen; Ajax the Lesser wrests Cassandra from the altar of Athena, incurring physical damage to the idol. The Greeks determine that they should stone Ajax in retribution, but he in turn also takes refuge at the altar of Athena. Odysseus kills Hector's baby son Astyanax and Neoptolemus takes Hector's wife Andromache captive. The Greeks make a human sacrifice of Priam's daughter Polyxena at Achilles' tomb. Athena formulates a plan to inflict revenge upon the Greeks concurrent with their nautical return.

Editions

[edit]- Online editions (English translation):

- Fragments of the Iliou persis translated by H.G. Evelyn-White, 1914 (public domain)

- Fragments of complete Epic Cycle translated by H.G. Evelyn-White, 1914; Project Gutenberg edition

- Print editions (Greek):

- A. Bernabé 1987, Poetarum epicorum Graecorum testimonia et fragmenta pt. 1 (Leipzig: Bibliotheca Teubneriana)

- M. Davies 1988, Epicorum Graecorum fragmenta (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht)

- Print editions (Greek with English translation):

- M.L. West 2003, Greek Epic Fragments (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press)

References

[edit]- Abrantes, M.C. (2016), Themes of the Trojan Cycle: Contribution to the study of the greek mythological tradition (Coimbra). ISBN 978-1530337118

- Burgess, Jonathan S., The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle, The Johns Hopkins University Press, (2004). ISBN 0-8018-6652-9. (p. 180).

- Davies, Malcolm; Greek Epic Cycle, Duckworth Publishers; 2 edition (May 2, 2001). ISBN 1-85399-039-6.

- Evelyn-White, Hugh G., Hesiod the Homeric Hymns and Homerica, BiblioBazaar (March 13, 2007). ISBN 1-4264-7293-5.