The Ring (2002 film)

| The Ring | |

|---|---|

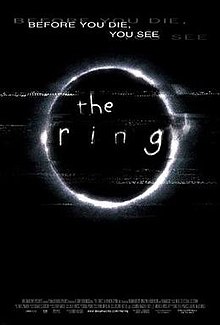

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gore Verbinski |

| Screenplay by | Ehren Kruger |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Bojan Bazelli |

| Edited by | Craig Wood |

| Music by | Hans Zimmer |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $48 million[3] |

| Box office | $249.3 million[3] |

The Ring is a 2002 American supernatural horror film directed by Gore Verbinski and written by Ehren Kruger. Starring Naomi Watts, Martin Henderson, David Dorfman, and Brian Cox, the film focuses on Rachel Keller (Watts), a journalist who discovers a cursed videotape that causes its viewers to die seven days later. It is a remake of Hideo Nakata's 1998 film Ring, based on the 1991 novel by Koji Suzuki.

The Ring was theatrically released in the United States on October 18, 2002, by DreamWorks Pictures. It was a box-office success, grossing $249.3 million worldwide on a $48 million budget, making it one of the highest-grossing horror remakes of all time. The Ring received mixed-to-positive reviews, with critics in particular praising the atmosphere and visuals, Bojan Bazelli's cinematography, Verbinski's direction and the performances of the cast (particularly Watts). At the 29th Saturn Awards, the film won in two categories: Best Horror Film and Best Actress (for Watts).

The film is the first installment of the American Ring series, and is followed by The Ring Two (2005) and Rings (2017). The success of The Ring inspired American remakes of several other Asian and Japanese horror films, including The Grudge (2004) and Dark Water (2005).

Plot

[edit]Teenage girls Katie and Becca discuss an urban legend about a cursed videotape that causes whoever views it to die in one week. That night, Katie, who viewed it one week ago, is killed by an unseen force.

At Katie's funeral, her mother asks her sister Rachel, a Seattle-based journalist, to investigate her daughter's death. Rachel discovers that Katie's friends all died in bizarre accidents at the same time as Katie's death. Rachel visits the Shelter Mountain Inn, where Katie and her friends saw the tape. She finds and views the tape; it contains strange and frightening imagery. She then receives a phone call from an unknown caller who whispers, "Seven days". Though initially skeptical, Rachel quickly begins to experience supernatural occurrences linked to the tape.

Rachel recruits the help of her video analyst ex-husband Noah. He views the tape and Rachel makes him a copy. She identifies a woman on the tape: horse breeder Anna Morgan, who committed suicide after some of her horses drowned themselves off Moesko Island. Rachel and Noah's 8-year-old son Aidan watches the tape. Aidan also possesses supernatural abilities, which he uses to help with Rachel's investigation.

Rachel heads for Moesko Island to speak to Anna's widower Richard, while Noah travels to Gale Psychiatric Hospital to view Anna's medical files. Rachel discovers that Anna had adopted a girl, Samara, who possessed the ability to psychically etch images onto objects and into people's minds, tormenting her parents and their horses. Noah finds a psychiatric file on Samara that mentions a terrifying video record last seen by Richard.

Returning to the Morgan home, Rachel finds a fake birth certificate proving that Samara is not the biological child of Richard and Anna. She also discovers the missing video, in which Samara explains her powers during a therapy session. Richard insists that Samara is evil and commits suicide by electrocuting himself. Noah and Rachel find a loft in the barn, which the Morgans used to isolate Samara from themselves and the outside world. There is an image of a tree behind the wallpaper; Rachel recognizes it as a tree at the Shelter Mountain Inn.

They return to Shelter Mountain Inn, led to a well beneath the floorboards. Rachel falls inside and experiences a vision of Anna dumping Samara into the well, where she survived for one week. Samara's body surfaces from the water. After Rachel is rescued, they arrange a proper burial for Samara.

Back home, Aidan warns Rachel that it was a mistake to help Samara. Rachel realizes that Noah's week is up; Samara's ghost crawls out of his TV screen and kills him. Initially unable to deduce why she was spared, Rachel realizes that the tape seen by Noah was a copy she had created. Rachel saves Aidan by having him make another copy to show someone else. Aidan asks what will happen to the person who views the copy, to which Rachel does not answer.

Cast

[edit]- Naomi Watts as Rachel Keller

- Martin Henderson as Noah Clay

- David Dorfman as Aidan Keller

- Daveigh Chase as Samara Morgan

- Brian Cox as Richard Morgan

- Shannon Cochran as Anna Morgan

- Jane Alexander as Dr. Grasnik

- Lindsay Frost as Ruth Embry

- Amber Tamblyn as Katherine "Katie" Embry

- Rachael Bella as Rebecca "Becca" Kotler

- Richard Lineback as Innkeeper

- Pauley Perrette as Beth

- Sara Rue as Babysitter

- Sasha Barrese as Girl Teen #1

- Tess Hall as Girl Teen #2

- Adam Brody as Kellen

- Michael Spound as Dave Embry

- Chris Cooper as a child murderer (cut from film)[4]

- Joe Chrest as Dr. Scott (uncredited)

- Maury Ginsberg as a video store clerk (DVD deleted scenes) (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Development and casting

[edit]The Ring went into production without a completed script.[5] Ehren Kruger wrote three drafts of the screenplay before Scott Frank came on to do an uncredited re-write. Gore Verbinski was initially inspired to do a remake of Ring after Walter F. Parkes sent him a VHS copy of the Japanese film, which he described as "intriguing", "pulp" and "avant-garde". The original WGA-approved credits listed Hiroshi Takahashi (writer of the original 1998 screenplay for Ring) but his name is absent from the final print.

Several high-profile actresses were offered the lead role, including Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Connelly and Kate Beckinsale.[6] Verbinski admitted to not wanting to cast "big stars" as he wanted his film to be "discovered" and described the wave of harsh criticism from hardcore fans of the original Japanese film as "inevitable", although he expressed desire for them to find the remake equally compelling. He also sought to retain the minimalism prevalent throughout Ring and set it in Seattle, due to its "wet and isolated" atmosphere.[5]

Filming

[edit]

The Ring was filmed in 2001, primarily in the State of Washington in numerous locations, including Seattle, Port Townsend, Whidbey Island, Bellingham, Monroe and Stanwood.[7] The Yaquina Head Lighthouse in Newport, Oregon, was also used as a filming location,[8] as well as Oregon's Columbia River Gorge.

Chris Cooper played a murderer in two scenes meant to bookend the film, but was ultimately cut.[4]

The film's cinematography by Bojan Bazelli is noted for its soft lighting and grey blue-green color. Shot on film, the production is unusual for achieving its color correction in-camera using 81EF and one of two green filters,[a][9] thereby committing to the film's visual style early, rather than relying on digital grading during post-production. The soft lighting was achieved by "diffusing the fill sources enough to match [the natural lighting]"[9] through the use of up to three layers of shades, HMIs and CTB,[b] and set up to create as little shadow as possible to "subconsciously alter the viewer's sense of perception and add a heightened sense of ambiguity."[11]

Title

[edit]As with the original Japanese film Ring, the title of The Ring can be interpreted as referring to the telephone call which warns those who watched the cursed tape that they will die in seven days,[12] as well as to the view of the ring of light seen from the bottom of the well where Samara was left to die.[13]

Score

[edit]The film features an original score composed by Hans Zimmer (who would later collaborate on Verbinski's other works). The soundtrack release did not coincide with the film's original 2002 theatrical run. It was released in 2005, accompanying The Ring's 2005 sequel in an album that combined music from both the first and second film. The soundtrack contains a few themes associated with the characters, moods and locations, including multiple uses of the Dies irae theme. The score makes use of string instruments, pianos and synthesizers.[14]

| The Ring / The Ring Two (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | March 15, 2005 |

| Recorded | 2002‒2005 |

| Length | 63:50 |

| Label | Decca |

All music is composed by Hans Zimmer, Henning Lohner and Martin Tillman

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Well" | Hans Zimmer, Henning Lohner | 11:24 |

| 2. | "Before You Die You See the Ring" | Zimmer | 7:09 |

| 3. | "This Is Going to Hurt" | Zimmer, Martin Tillman | 2:48 |

| 4. | "Burning Tree" | Zimmer, Lohner, Tillman, Trevor Morris | 10:13 |

| 5. | "Not Your Mommy" | Zimmer, Lohner, Clay Duncan | 3:59 |

| 6. | "Shelter Mountain" | Zimmer, Tillman, Morris | 4:10 |

| 7. | "The Ferry" | Zimmer, Lohner, Tillman, Morris, Bart Hendrickson | 3:15 |

| 8. | "I'll Follow Your Voice" | Zimmer, Lohner | 6:28 |

| 9. | "She Never Sleeps (Remix)" | 2:17 | |

| 10. | "Let the Dead Get In (Remix)" | 3:59 | |

| 11. | "Seven Days (Remix)" | 3:24 | |

| 12. | "Television (Remix)" | 4:00 | |

| Total length: | 63:50 | ||

Release and reception

[edit]Marketing

[edit]To advertise The Ring, many promotional websites were formed featuring characters and places in the film. The video from the cursed videotape was played in late-night programming over the summer of 2002 without any reference to the film. Physical VHS copies were also randomly distributed outside of movie theaters by placing the tapes on the windshields of people's cars.[4][15]

Box office

[edit]The Ring opened theatrically on October 18, 2002 in the United States, on 1,981 screens, and grossed $15,015,393 during its opening weekend.[16][3] The film went on to become a sleeper hit,[17] leading DreamWorks to expand its release to 700 additional theaters.[3] It ultimately grossed $129,128,133 in the United States.[3] In Japan, the film earned $8.3 million in the first two weeks of its release.[18] Worldwide, The Ring grossed a total of $249,348,933.[3]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 71% based on 210 reviews, with an average rating of 6.6/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "With little gore and a lot of creepy visuals, The Ring gets under your skin, thanks to director Gore Verbinski's haunting sense of atmosphere and an impassioned performance from Naomi Watts".[19] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 57 out of 100, based on 36 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[20] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave The Ring an average grade of "B−" on an A+ to F scale.[21]

On Ebert & Roeper, Richard Roeper gave the film "Thumbs Up" and said it was very gripping and scary despite some minor unanswered questions. Roger Ebert gave the film "Thumbs Down" and felt it was boring and "borderline ridiculous"; he also disliked the extended, detailed ending.[22] Jeremy Conrad from IGN praised The Ring for its atmospheric set up and cinematography, and said that "there are disturbing images ... but the film doesn't really rely on gore to deliver the scares".[23] Film Threat's Jim Agnew called it dark, disturbing and original.[24]

Despite the praise given to the direction, some criticized the lack of character development. Jonathan Rosenaum from the Chicago Reader said that the film was "an utter waste of Watts ... perhaps because the script didn't bother to give her a character",[25] whereas William Arnold from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer disagreed, claiming that she projects intelligence, determination and resourcefulness in the film.[26] Several critics, like Miami Herald's Rene Rodriguez and USA Today's Claudia Puig,[27] found themselves confused and thought "for all the time [the film] spends explaining, it still doesn't make much sense".[28]

Accolades

[edit]| Year | Award | Category | Nomination(s) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Saturn Awards[29] | Best Movie – Horror | Won | |

| Best Actress | Naomi Watts | Won | ||

| 2003 | MTV Movie Awards[30] | Best Movie | Nominated | |

| Best Villain | Daveigh Chase | Won | ||

| Teen Choice Awards[31] | Best Movie – Horror | Won | ||

Legacy

[edit]The success of The Ring paved the way for American remakes of several other Asian and Japanese horror films, including The Grudge (2004), Dark Water (2005), Shutter and The Eye (both 2008).[32][33]

The Ring ranked number 20 on the cable channel Bravo's list of The 100 Scariest Movie Moments. Bloody Disgusting ranked it sixth in their list of the "Top 20 Horror Films of the Decade", with the article saying that "The Ring was not only the first American 'J-horror' remake out of the gate; it also still stands as the best".[34]

Sequels

[edit]A sequel, titled The Ring Two, was released on March 18, 2005. A short film, titled Rings, was also released in 2005, and is set between The Ring and The Ring Two. A third installment, also titled Rings, was released on February 3, 2017.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The source writes '85EFs' here, which do not exist; a likely typo. The green filters are specified as +14 and +7 points of green printer lights

- ^ "C.T.B. stands for Color Temperature Blue. This is an abbreviation for the color correction gels used in lighting to convert the color temperature from tungsten to daylight. They come in gradients: Quarter Blue, Half Blue, Full Blue."[10]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Ring (15)". British Board of Film Classification. October 21, 2002. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Ring". American Film Institute. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Ring (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cormier, Roger (October 18, 2017). "15 Must-Watch Facts About The Ring". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "Interview with Gore Verbinski". curseofthering.com. 2002. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (November 1, 2002). "How Naomi Watts became the Ring leader". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 25, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Lloyd, Sarah Anne (October 14, 2019). "Relive 'The Ring' in these spooky Seattle-area locations". Curbed. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Seibold, Witney (December 28, 2021). "The Haunted History Of The Lighthouse From The Ring". /Film. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Holben, Jay (November 2002). "Death Watch". American Cinematographer Vol. 83 No. 11 P. 50-59. Archived from the original on February 13, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)(subscription required) - ^ "Film School for Filmmakers, Producers, and Screenwriters". February 24, 2023. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ "Ring, The: Production Notes". www.cinema.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

Bazelli expounds, "In lighting the sets and the actors, we tried to eliminate all the shadows cast by the actors, which is meant to subconsciously alter the viewer's sense of perception and add a heightened sense of ambiguity."

- ^ Sherman, Dale (2013). Armageddon Films FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Zombies, Contagions, Aliens and the End of the World as We Know It!. Applause Books. ISBN 978-1617131196.

The story goes that seven days after viewing the tape, those who watch will receive a phone call (hence the first interpretation of 'the ring') [...]

- ^ Silverblatt, Art; Zlobin, Nikolai (2004). International Communications: A Media Literacy Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-0765609748.

- ^ Hasan, Mark (2006). "CD/LP Review: The Ring". KQEK. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Caister, Victoria Rose (April 14, 2021). "This Horror Film Basically Created The Idea Of Viral Marketing". Game Rant. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Ring reigns at the box office". The Globe and Mail. October 21, 2002. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Ring review". Empire. 2003. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Friend, Tad (May 25, 2003). "Remake Man". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "The Ring". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Ring". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 20, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Ring" in the search box). CinemaScore. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 18, 2002). "The Ring Movie Review & Film Summary (2002)". RogerEbert. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Conrad, Jeremy (February 28, 2003). "The Ring". IGN. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Ring". FilmSpot. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ "The Ring". The Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- ^ Arnold, William (October 12, 2002). "'The Ring' is plenty scary but the plot is a bit hairy". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (October 17, 2002). "'Ring' has hang-up or two". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rene (October 18, 2002). "Movie: The Ring (2002)". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on June 21, 2003. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Minority Report & Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers Win Big At The 29th Annual Saturn Awards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ "2003 MTV Movie Awards". MTV. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ^ "2003 Teen Choice Awards Nominees". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. June 18, 2003. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ Kurland, Daniel (December 31, 2019). "The Ring Is The Best Japanese Horror Remake". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Polino, Joey (February 6, 2008). "'The Eye' is not your standard horror remake". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ "00's Retrospect: Bloody Disgusting's Top 20 Films of the Decade...Part 3". Bloody Disgusting. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

External links

[edit]- The Ring at IMDb

- The Ring at AllMovie

- The Ring at Box Office Mojo

- The Ring at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2002 films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s ghost films

- 2000s Japanese films

- 2000s serial killer films

- 2002 horror films

- American ghost films

- American horror thriller films

- American mystery films

- American remakes of Japanese films

- American serial killer films

- American supernatural drama films

- American supernatural horror films

- Asian-American horror films

- Cases of people who fell into a well in fiction

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- Films about filicide

- Films about curses

- Films about death

- Films about families

- Films about journalists

- Films about mother–son relationships

- Films about television

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on horror novels

- Films based on Japanese novels

- Films directed by Gore Verbinski

- Films produced by Walter F. Parkes

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films scored by Henning Lohner

- Films set in 1978

- Films set in 2002

- Films set in Seattle

- Films set in Washington (state)

- Films set on fictional islands

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Oregon

- Films shot in Seattle

- Films shot in Washington (state)

- Films with screenplays by Ehren Kruger

- Horror film remakes

- The Ring (franchise)

- Saturn Award–winning films

- Techno-horror films

- Teen Choice Award winning films

- English-language horror films

- English-language crime films