Innocence of Muslims

| Innocence of Muslims | |

|---|---|

| Produced by | Sam Bacile |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 14 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50,000 - $60,000 |

Innocence of Muslims[1][2] is a 2012 anti-Islamic short film that was written and produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula.[3][4] Two versions of the 14-minute video were uploaded to YouTube in July 2012, under the titles "The Real Life of Muhammad" and "Muhammad Movie Trailer".[5] Videos dubbed in Arabic were uploaded during early September 2012.[6] Anti-Islamic content had been added in post-production by dubbing, without the actors' knowledge.[7]

What was perceived as denigration of the Islamic prophet Muhammad resulted in demonstrations and violent protests against the video to break out on September 11 in Egypt and spread to other Arab and Muslim nations as well as to some western countries. The protests led to hundreds of injuries and over 50 deaths.[8][9][10][11] Fatwas calling for the harm of the video's participants were issued and Pakistani government minister Ghulam Ahmad Bilour offered a bounty for the killing of Nakoula, the producer.[12][13][14] The film has sparked debates about freedom of speech and Internet censorship.[15]

Plot and description

The video titled "The Real Life of Muhammad", uploaded on July 1, 2012, has a running time of 13:03 in 480p format. The video "Muhammad Movie Trailer" was uploaded on July 2, 2012, with a running time of 13:51 in 1080p format. They are similar in content.

The trailer opens with a scene portraying the reportedly increasing persecution of Copts and poor human rights in Egypt around the time of the film's production, with increases in church burnings, religious intolerance and sectarian violence against the 10% population of Egypt that are Copts, as well as complaints that authorities have failed to protect this population.[16] The New York Times stated: "The trailer opens with scenes of Egyptian security forces standing idle as Muslims pillage and burn the homes of Egyptian Christians. Then it cuts to cartoonish scenes depicting the Prophet Muhammad as a child of uncertain parentage, a buffoon, a womanizer, a homosexual, a child molester, and a greedy, bloodthirsty thug."[17]

Most references to Islam were overdubbed over the original spoken lines after filming had been completed.[18] The film's 80 cast and crew members have disavowed the film: "The entire cast and crew are extremely upset and feel taken advantage of by the producer. ... We are deeply saddened by the tragedies that have occurred."[19]

The script was originally about life in Egypt 2,000 years ago and was titled Desert Warrior.[20] It was a story about a character called "Master George". Several actors were brought in to overdub lines. They were directed to say specific words, such as "Muhammad".[21] The trailer opens in a medical office, where a presumably Muslim police officer is bragging to Copts, including a doctor, about Muhammad's polygamous romantic life, and implying that Muhammad's marital and sexual practices are a model for all Muslim men. The Copts remain unimpressed, and one of them replies with sarcasm, thus irritating the police officer. The scene then cuts to anti-Coptic mob attacks taking place outside the clinic. As an Islamic call to prayer is sung from somewhere in the area, Muslims are shown committing arson and looting a business which appears to be the clinic, as police do nothing. A young woman wearing a cross is apparently murdered by the rioters. In the final shot of this segment, the police officer who had earlier been arguing in the clinic is seen standing passively in the street, holding some unidentified items presumably looted from the targeted businesses.

In the next scene, the doctor and his family, hiding from the anti-Coptic attacks, take shelter in their home, where the doctor informs two women, implied to be his wife and daughter, that the "angry mob in the city" is the "Islamic Egyptian Police". Presumably after the attack is over, he mentions that they had arrested 1,400 Christians, tortured them, and forced them to confess to "the killings". His daughter asks why they are doing this, to which her father responds "to protect Islamic crimes". The doctor then implies that a crackdown on the violence would save lives and taxpayers' money.

Following this exchange, the doctor takes up a marker and begins writing on a whiteboard: "Man + X = BT". "BT" is overdubbed as "Islamic terrorist". His daughter asks what "X" is. He tells her that she needs to discover that for herself. It is implied X is Muhammad, though the issue is never raised again.

The video continues with scenes set in pre-Islamic and early-Islamic Arabia. It starts with Muhammad supposedly being born 4 years after his father died. Some scenes depict the main character referred to in overdubbing as "Muhammad". In one scene, the "Muhammad" character's wife, "Khadija", suggests mixing parts of the Torah and the New Testament to create the Quran.[22] In another scene, Muhammad is seen speaking to the donkey known as Yaʽfūr in Islamic tradition.[23] It goes on to suggest that Muhammad was a rapist, pedophile, homosexual, and supported religious persecution, and that these actions were written into the Quran and contributed to the buildup of Islamist terrorist attacks.

Reviews

A Vanity Fair article described the video as "Exceptionally amateurish, with disjointed dialogue, jumpy editing, and performances that would have looked melodramatic even in a silent movie, the clip is clearly designed to offend Muslims, portraying Mohammed as a bloodthirsty murderer, Lothario and pedophile with omnidirectional sexual appetites."[24]

Reuters said "it portrays Mohammad as a fool, a philanderer and a religious fake and in one clip posted on YouTube, he was shown in an apparent sexual act with a woman. For many Muslims it is blasphemous even to show a depiction of the Prophet."[25]

Filmmaker and promoters

The movie was written and produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, using the pseudonym of "Sam Bacile".[3][4][26] Nakoula claimed that he was creating an epic, two-hour film but no such film has come to light.[27]

The project was promoted by Morris Sadek by email and on the blog of the National American Coptic Assembly.[28]

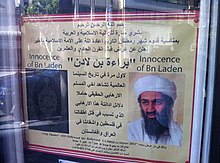

According to a consultant on the project, the videos are "trailers" from a full-length film that was shown only once, to an audience of fewer than ten people, at a rented theater in Hollywood, California. Posters advertising the film used the title Innocence of Bin Laden.[29] The film's original working title was Desert Warrior, and it told the story of "tribal battles prompted by the arrival of a comet on Earth".[30] On September 27, 2012, U.S. federal authorities stated Nakoula was arrested in Los Angeles for allegedly violating terms of his probation. Prosecutors stated that some of the violations included making false statements regarding his role in the film and his use of the alias "Sam Bacile".[31] On November 7, 2012, Nakoula pleaded guilty to four of the charges against him and was sentenced to one year in prison and four years of supervised release.[32][33]

Production

In July 2011, Nakoula started casting actors for Desert Warrior, the working title at that time.[20] The independent film was directed by a person first identified in casting calls[34] as Alan Roberts, whose original cut and filmed dialog and script did not include references to Muhammad or Islam.[35] According to the casting.backstage.com announcement, it was to be "an HD 24P historical Arabian Desert adventure film" with "Sam Bassiel" as producer with shooting to start in August 2011. The lead was to be "George: male, 20–40, a strong leader, romantic, tyrant, a killer with no remorse, accent".

American non-profit Media for Christ obtained film permits to shoot the movie in August 2011, and Nakoula provided his home as a set and paid the actors, according to government officials and those involved in the production.[36] Joseph Nassralla Abdelmasih, president of Media for Christ, claimed that the company's name was used without his knowledge. He also stated that the film was edited afterwards without Media's involvement.[37] Steve Klein, an anti-Muslim and self-styled counter-jihad activist was hired as a consultant, and was relied on to sharpen the film's Islamophobic framing.[38] Nasralla has however also been noted to have had close ties both to Klein and to the counter-jihad movement.[39] Klein later appeared publicly claiming to be the spokesman for the film.[40] Klein told journalist Jeffrey Goldberg that despite previous claims, "Bacile" is not a real person and is neither Israeli nor Jewish and that the name is a pseudonym.[41] Israeli authorities found no sign of his being an Israeli citizen,[42] and there was no indication of a "Sam Bacile" living in California or participating in Hollywood filmmaking.[43]

By September 13, 2012, "Sam Bacile" was identified as Nakoula Basseley Nakoula, a 55-year-old Coptic Christian from Egypt living near Los Angeles, California,[44] with known aliases.[45] In the 1990s, he served time in prison for manufacturing methamphetamine.[44][46] He pleaded no contest in 2010 to bank fraud charges, was sentenced to 21 months in prison,[44][46] and was released on probation in June 2011.[47] Nakoula claims to have written the script while in prison and raised between $50,000 and $60,000 from his wife's family in Egypt to finance the film.[3][48] The FBI contacted him due to the potential for threats, but said he was not under investigation.[49] On September 27, 2012, U.S. federal authorities arrested Nakoula in Los Angeles for suspicion of violating terms of his probation. Violations included making false statements regarding his role in the film and his use of the alias "Sam Bacile". On November 7, 2012, Nakoula pleaded guilty to four of the charges against him and was sentenced to one year in prison and four years of supervised release.[32][33]

Law professor Stephen L. Carter[50] and constitutional law expert Floyd Abrams[51] have each stated that the government cannot prosecute the film's producer for its content because of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects freedom of speech in the United States.

Screening and Internet upload

The video production "Innocence of Bin Laden" was advertised in the Anaheim-based newspaper Arab World during May and June 2012. The advertisement cost $300 to run three times in the paper and was paid by an individual identified only as "Joseph". The advertisements were noted by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), whose Islamic affairs director stated, "When we saw the advertisement in the paper, we were interested in knowing if it was some kind of pro-jihadist movie." Brian Donnelly, a guide for a Los Angeles based tour of famous crime scenes who noticed the poster advertising at the Vine Theater, said, "I didn't know if it was a good thing or a bad thing. We didn't know what it was about because we can't read Arabic."[52] The earlier version of the film was screened once at the Vine Theater of June 23, 2012 to an audience of only ten people. The film had no subtitles and was presented in English. An employee of the theater stated, "The film we screened was titled The Innocence of Bin Laden", and added that it was a "small viewing".[53]

A second screening was planned for June 30, 2012. A local Hollywood blogger, John Walsh, attended a June 29 Los Angeles City Council meeting, where he raised his concerns about the title of a film to be screened that appeared to support the leader of al-Qaeda. He said "There is an alarming event occurring in Hollywood on Saturday. A group has rented the Vine Street theater to show a video entitled Innocence of Bin Laden. We have no idea what this group is." The blog site reported that the June 30 screening had been canceled.[54][55] A Current TV producer photographed the poster while it was being displayed at the theater as advertising to later discuss on the talk show The Young Turks.[56] The poster did not denigrate Muslims, but rather referred to "my Muslim brother". In a translation provided by the ADL, the poster stated it would reveal "the real terrorist who caused the killing of our children in Palestine, and our brothers in Iraq and Afghanistan",[57] a phrase that has been used by Palestinians to protest U.S. support of Israel.[58]

The film was supported and promoted by pastor Terry Jones, known for a Quran-burning controversy, which also led to riots around the world.[59] Jones said that he planned to show a 13-minute trailer at his church, the Dove World Outreach Center in Gainesville, Florida, on September 11, 2012.[60] It was reported on September 14, 2012, that a planned screening by a Hindu organization in Toronto would be coupled with "snippets from other movies that are offensive to Christians and Hindus". Because of security concerns, no public venue was willing to show the film, although the group still planned on showing the film in the future to a private audience of about 200 people.[61][62] Siobhán Dowling of The Guardian reported that "a far-right Islamophobic group in Germany", the Pro Germany Citizens' Movement, had uploaded the trailer on their own website and wanted to show the entire film, but authorities were attempting to prevent it.[63]

Blocking of the YouTube video

The video clips were posted to YouTube on July 1 by user "sam bacile";[5] however, by September, the film had been dubbed into Arabic and was drawn to the attention of the Arabic-speaking world by blogger Morris Sadek. Sadek's own Egyptian citizenship had been revoked.[64] A two-minute excerpt dubbed in Arabic was broadcast on September 9 by Sheikh Khalad Abdalla.[65][66]

YouTube voluntarily blocked the video in Egypt and Libya, and blocked the video in Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, India, and Singapore due to local laws, while Turkey, Brazil, and Russia initiated steps to get the video blocked.[67][68][69] Google, Inc., the owner of YouTube, also blocked the video in Libya and Egypt citing "the very difficult situation" in those countries.[70] In September 2012, the governments of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sudan, and Pakistan blocked YouTube for not removing the video, saying that the website would remain suspended until the film was removed.[71][72][73] Government authorities in Chechnya and Dagestan issued orders to internet providers to block YouTube, and Iran announced that it was blocking Google and Gmail.[74][75][76] Google also agreed to block the anti-Islamic movie in Jordan.[73]

The White House asked YouTube to review whether to continue hosting the video at all under the company's policies. YouTube said the video fell within its guidelines as the video is against Islam, but not against Muslim people, and thus not considered "hate speech".[68] Ben Wizner of the American Civil Liberties Union said of this, "It does make us nervous when the government throws its weight behind any requests for censorship."[77]

Ninth Circuit court rulings on removal

On February 26, 2014, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ordered YouTube to remove the video from its website by a 2–1 majority. The ruling was in response to a complaint by actress Cindy Lee Garcia, who had objected to the use of her performance, which had been partially dubbed for its inclusion in Innocence of Muslims. Garcia had believed during production that she was appearing in a film called Desert Warrior, which was described as a "historical Arabian Desert adventure film", and was unaware that anti-Islamic material would be added at the post-production stage. Garcia had argued that she held a copyright interest in her performance.[78][79]

In May 2015, in an en banc opinion, the Ninth Circuit reversed the panel's decision, vacating the order for the preliminary injunction.[80][81][82] Ibrahim Hooper, the National Communications Director and spokesperson for the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), advised that people should not watch the film.[83]

Reactions and controversies

Protests were held in many nations, through Islamic countries in the Middle East,[84][85] Asia,[86][87] and Africa[86] as well as the United Kingdom,[86][88] France,[89] the Netherlands,[90] and Australia.[91][92] Numerous eyewitnesses reported that the 2012 Benghazi attackers said they were motivated by the video.[93][94][95][96][97][98]

Ghulam Ahmad Bilour offered a $100,000 award for killing the maker of the film.[99] Ahmad Fouad Ashoush, a Salafist Muslim cleric, issued a fatwa saying: "I issue a fatwa and call on the Muslim youth in America and Europe to do this duty, which is to kill the director, the producer and the actors and everyone who helped and promoted the film."[100] Protesters in Pakistan called for the execution of the filmmaker and urged Islamabad to close the US Embassy and expel its diplomats; the protests left dozens dead.[101][102][103] In Sindh, Pakistan, a crowd of 15,000 torched "six cinemas, three Hindu temples, two banks, a post office and 5 police vehicles," and murdered two police officers. A suicide bombing in Afghanistan was in response to the film.[104]

See also

- 2005 Quran desecration controversy

- 2012 Afghanistan Quran burning protests

- Fitna (2008) and subsequent protests and trial

- Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- The Message (1976 film)

- The Satanic Verses controversy

- South Park controversies § Censorship of the depiction of Muhammad

- Submission (2004)

References

- ^ "Anti-Muslim film got LA County permit for shoot". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. September 20, 2012. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

Anti-Muslim film had permit allowing 1-day shoot at LA County ranch, use of fire, animals

- ^ "County of Los Angeles Releases Redacted Film Permit for "Desert Warriors"" (PDF). FilmLA. September 20, 2012. f00043012. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

NOTE: This document has been redacted due to concerns for safety and security of persons and locations

- ^ a b c Esposito, Richard; Ross, Brian; Galli, Cindy (September 13, 2012). "Anti-Islam Producer Wrote Script in Prison: Authorities, 'Innocence of Muslims' Linked to Violence in Egypt, Libya". abcnews.go.com. ABC News. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Dion Nissenbaum; James Oberman; Erica Orden (September 13, 2012). "Behind Video, a Web of Questions". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Zachary Zahos (September 19, 2012). "The Art of Defamation". The Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Lovett, Ian (September 15, 2012). "Man Linked to Film in Protests Is Questioned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Dan Murphy (September 12, 2012). "There-may-be-no-anti-Islamic-movie-at-all". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Death, destruction in Pakistan amid protests tied to anti-Islam film". CNN. September 21, 2012. Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ "Egypt newspaper fights cartoons with cartoons". CBS News. Associated Press. September 26, 2012. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ Latest Protests Against Depictions of Muhammad retrieved 1 October 2012 [dead link]

- ^ Rice, Susan (2019). Tough Love. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 314.

- ^ Fatwa issued by Muslim cleric against participants in an anti-Islamic film retrieved 1 October 2012 Archived October 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Egypt cleric issues fatwa against 'Innocence of Muslims' cast retrieved 1 October 2012 [dead link]

- ^ "Anti-Islam film: US condemns Pakistan minister's bounty". BBC News. September 23, 2012. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ Thomas Fenton (September 12, 2012). "Should Innocence of Muslims be censored?". Global Post. Archived from the original on October 1, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ Egypt and Libya: A Year of Serious Abuses Archived July 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Human rights watch, January 24, 2010

- ^ David D. Kirkpatrick (September 12, 2012). "Anger Over a Film Fuels Anti-American Attacks in Libya and Egypt". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ Sarah Abdurrahman (September 12, 2012). "Why Are All the Religious References in "Innocence of Muslims" Dubbed?". On the Media. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ "Pentagon to review video of Libya attack – This Just In – CNN.com Blogs". News.blogs.cnn.com. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Noah Shachtman with Robert Beckhusen (September 13, 2012). "Anti-Islam Filmmaker Went by 'P.J. Tobacco' and 13 Other Names". Wired. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ Marquez, Miguel (September 17, 2012). "Actor: Anti-Islam filmmaker 'was playing us along'". CNN. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "West urges end to file protests". BBC. September 14, 2012. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Robert Mackey; Liam Stack (September 11, 2012). "Obscure Film Mocking Muslim Prophet Sparks Anti-U.S. Protests in Egypt and Libya". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Gross, Michael Joseph (December 27, 2012). "The Making of The Innocence of Muslims: Cast Members Discuss the Film That Set Fire to the Arab World". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Spetalnick, Matt (September 12, 2012). "Obama vows to track down ambassador's killers". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 7, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ Gillian flaccus (September 12, 2012). "California man confirms role in anti-Islam film". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Paul Bond (September 19, 2012). "Does 'Innocence of Muslims' Actually Exist?". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Constable, Pamela (September 13, 2012). "Egyptian Christian activist in Virginia promoted video that sparked furor". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ Willon, Phil (September 14, 2012). "Anti-Muslim film poster in Hollywood surprised locals". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ Kia Makarechi (September 17, 2012). "Anna Gurji & 'Innocence Of Muslims': Horrified Actress Writes Letter Explaining Her Role". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ RISLING, GREG (September 28, 2012). "Calif. man behind anti-Muslim film ordered jailed". Yahoo News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Kim, Victoria (November 7, 2012). "'Innocence of Muslims' filmmaker gets a year in prison". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Time Waster (September 27, 2012). "Feds Arrest Producer Of Controversial Anti-Islam Film On Probation Violation Charge". The Smoking Gun. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ^ "Audition & Casting Calls for Movie, Theatre, TV, Dance & More - Backstage". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Yamato, Jen (September 14, 2012). Was Inflammatory 'Innocence Of Muslims' Film Directed By 'Karate Cop,' 'Happy Hooker' Schlock Veteran? Archived September 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Movieline

- ^ Ryan, Harriet; Garrison, Jenna (September 13, 2012). Christian charity, ex-con linked to film on Islam. Archived September 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times

- ^ Mark Hosenball (September 19, 2012). "U.S. activist says he was deceived over anti-Muslim film". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Blumenthal, Max (2020). The Management of Savagery: How America's National Security State Fueled the Rise of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Donald Trump. Verso. p. 153. ISBN 9781788732307.

- ^ "Filmskapare kopplas till Counterjihad-rörelsen". Expo (in Swedish). September 14, 2012.

- ^ Gillian Flaccus (September 14, 2012). "Anti-Muslim film promoter outspoken on Islam". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ "Muhammad Film Consultant: 'Sam Bacile' is Not Israeli, and Not a Real Name – Jeffrey Goldberg". The Atlantic. August 20, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder. "What We Know About Sam Bacile, The Man Behind The Muhammad Movie : The Two-Way". NPR. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "Sam Bacile Identity Doubted". Business Insider. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c Richard Verrier (September 14, 2012). "Was 'Innocence of Muslims' directed by a porn producer?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Kia Makarechi (September 14, 2012). "Alan Roberts & 'Innocence Of Muslims': Softcore Porn Director Linked To Anti-Islam Film". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "California Man Confirms Role in Anti-Islam Film". Time. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "Locate a Federal Inmate: Nakoula Basseley Nakoula". Federal Bureau of Prisons. 2012. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ "Alleged anti-Muslim film producer has drug, fraud convictions". Los Angeles Times. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ Moni Basu; Chelsea J. Carter (September 14, 2012). "Sam Bacile or Nakoula Basseley Nakoula? Federal officials consider Nakoula as man behind the film". WPTV. CNN. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ Carter, Stephen L. (September 23, 2012). "Anti-Muslim video incendiary but protected". The Press Democrat. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Abrams, Floyd (September 20, 2012). "Should YouTube Have Taken Down Incendiary Anti-Muslim Video?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Mona Shadia; Harriet Ryan (September 15, 2012). "California Muslims hold vigil for slain ambassador". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Hollie McKay (September 13, 2012). "'Innocence of Muslims' producer's identity in question; actors say they were duped, overdubbed". Fox News. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Jessica Garrison; Sam Quinones (September 13, 2012). "Anti-Muslim film screening: L.A. gadfly tried to warn city leaders". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Eric Lach (September 13, 2012). "L.A. Blogger Alerted City Council To Anti-Islam Film In June". TPM. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Ted Johnson (September 14, 2012). "White House presses YouTube on 'Muslims' pic". Variety. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ "California Muslims hold vigil for slain ambassador". Los Angeles Times. September 15, 2012. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Boston.com / Sept. 11". Archived from the original on May 6, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Terry Jones supports movie behind embassy bombing protests Archived October 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine retrieved 7 October 2012

- ^ "American Killed in Libya Attack". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Tom Godfrey (September 14, 2012). "Toronto Hindu group plans screening of Innocence of Muslims". QMI Agency. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Etan Vlessing (September 14, 2012). "Toronto 2012: Canadian Hindu Group Plans Screening of Controversial Anti-Islam Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Siobhán Dowling (September 16, 2012). "Far-right German group plans to show anti-Islamic film". guardiannews.com. London. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ "US envoy dies in Benghazi consulate attack". Al Jazeera English. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Mike Giglio (September 21, 2012). "Complaint Against Egyptian TV Host Who Aired 'Innocence of Muslims' Raises Free Speech Issue". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Max Fisher (September 11, 2012). "The Movie So Offensive That Egyptians Just Stormed the U.S. Embassy Over It". Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "Google blocks Singapore access to anti-Islam film". Yahoo! News. September 21, 2012. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Google Has No Plans to Rethink Video Status Archived May 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, September 14, 2012

- ^ ".:Middle East Online::Turkey seeks to ban online access to anti-Islam movie:". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Google blocks video clips in Egypt, Libya amid concerns over anti-Islam film". Al Arabiya. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "YouTube blocked in Pakistan for not removing anti-Islam film". New Delhi: New Delhi Television (NDTV). September 17, 2012. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Rory Mulholland, Fresh protests as prophet cartoons fuel Muslim fury Archived February 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, AFP.

- ^ a b "YouTube links to anti-Islam film blocked in Jordan". The Times of India. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ "Internet Providers In Chechnya Instructed To Block YouTube Over Anti-Islam Film". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. September 24, 2012. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Daghestan ISP Blocks YouTube Over Anti-Islamic Film". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. September 24, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Iran to block access to Google, Gmail amid anti-Islam film protests". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Activists troubled by White House call to YouTube Archived May 31, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Politico, September 14, 2012

- ^ Google ordered to remove anti-Islamic film from YouTube Archived March 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, February 26, 2014.

- ^ A controversial YouTube video haunts free speech again Archived March 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The New Yorker, March 4, 2014.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (May 18, 2015). "Google Wins Copyright And Speech Case Over 'Innocence Of Muslims' Video". NPR. Archived from the original on May 19, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (May 18, 2015). "Controversial 'Innocence of Muslims' Ruling Reversed By Appeals Court". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Garcia v. Google Archived May 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, no. 12-57302 (9th Cir. May 18, 2015)(en banc).

- ^ Huffington Post: "Anti-Islam Film Returns To YouTube, And These Muslim Leaders Want You To Ignore It" By Antonia Blumberg Archived May 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine May 20, 2015

- ^ al-Salhy, Suadad (September 13, 2012). "Iraqi militia threatens U.S. interests over film". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick (September 14, 2012). "Anti-American Protests Over Film Expand to More Than a Dozen Countries". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Anti-Islam film protests escalate". BBC. September 14, 2012. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ Hundreds of angry Afghans protest anti-Islam film in eastern Afghanistan – The Washington Post

- ^ "Protesters burn flags outside US embassy in London". The Daily Telegraph. September 14, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ "Over 100 arrested in protest of anti-Islam film outside U.S. embassy in Paris" Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine – Daily News (New York) . Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Demo closes American consulate, but took place on the Dam". DutchNews.nl. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "As it happened: Violence erupts in Sydney over anti-Islam film". ABC News. September 15, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Police gas Sydney protesters". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "US envoy dies in Benghazi consulate attack". Al Jazeera English. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ David D. Kirkpatrick, Election-Year Stakes Overshadow Nuances of Libya Investigation Archived February 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times October 16, 2012

- ^ Scott Shane, Clearing the Record About Benghazi Archived February 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times October 18, 2012

- ^ David D. Kirkpatrick, Attack by Fringe Group Highlights the Problem of Libya's Militias Archived April 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times 15 September 2012

- ^ "How Benghazi Is Reacting To The Deadly Attacks". National Public Radio. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Gertz, Matt (May 14, 2013). "Four Media Reports From Libya That Linked The Benghazi Attacks To The Anti-Islam Video". Media Matters For America. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ $100,000 bounty on Prophet film-maker, Francis Elliott & Aoun Sahl, The Times, page 28, Monday September 24, 2012

- ^ "Fatwa issued against 'Innocence of Muslims' film producer". Telegraph.co.uk. London. September 18, 2012. Archived from the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ AFP (September 14, 2012). "Protests across Pakistan against anti-Islam film". Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Day of reverence or killer rage?". Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - World". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Afghan woman's suicide bombing was revenge for anti-Islam film, says radical group". The Times of Israel. September 18, 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

External links

- 2012 films

- 2012 controversies

- 2012 YouTube videos

- American independent films

- American short films

- Art works that caused riots

- Blasphemy

- Biographies of Muhammad

- Censored films

- Counter-jihad

- Cultural depictions of Muhammad

- Egypt–United States relations

- Films about Muhammad

- Films critical of religion

- Films set in Egypt

- Anti-Islam works

- Islam-related mass media and entertainment controversies

- Libya–United States relations

- Online obscenity controversies

- Religiously motivated violence in Egypt

- Religious controversies in film

- United States–Yemen relations

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s American films

- Islamophobia in the United States