Diana, Princess of Wales

| Diana | |

|---|---|

| Princess of Wales (more) | |

Diana in June 1997 | |

| Born | Diana Frances Spencer 1 July 1961 Park House, Sandringham, England |

| Died | 31 August 1997 (aged 36) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Car crash |

| Burial | 6 September 1997 Althorp, Northamptonshire, England |

| Spouse | |

| Issue Detail | |

| Noble/royal house | |

| Father | John Spencer, 8th Earl Spencer |

| Mother | Frances Roche |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| |

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997) was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William and Harry. Her activism and glamour, which made her an international icon, earned her enduring popularity.

Diana was born into the British nobility and grew up close to the royal family, living at Park House on their Sandringham estate. In 1981, while working as a nursery teacher's assistant, she became engaged to Charles, the eldest son of Elizabeth II. Their wedding took place at St Paul's Cathedral in July 1981 and made her Princess of Wales, a role in which she was enthusiastically received by the public. The couple had two sons, William and Harry, who were then respectively second and third in the line of succession to the British throne. Diana's marriage to Charles suffered due to their incompatibility and extramarital affairs. They separated in 1992, soon after the breakdown of their relationship became public knowledge. Their marital difficulties were widely publicised, and the couple divorced in 1996.

As Princess of Wales, Diana undertook royal duties on behalf of the Queen and represented her at functions across the Commonwealth realms. She was celebrated in the media for her beauty, style, charm, and later, her unconventional approach to charity work. Her patronages were initially centred on children and the elderly, but she later became known for her involvement in two particular campaigns: one involved the social attitudes towards and the acceptance of AIDS patients, and the other for the removal of landmines, promoted through the International Red Cross. She also raised awareness and advocated for ways to help people affected by cancer and mental illness. Diana was initially noted for her shyness, but her charisma and friendliness endeared her to the public and helped her reputation survive the public collapse of her marriage. Considered photogenic, she is regarded as a fashion icon of the 1980s and 1990s.

In August 1997, Diana died in a car crash in Paris; the incident led to extensive public mourning and global media attention. An inquest returned a verdict of unlawful killing following Operation Paget, an investigation by the Metropolitan Police. Her legacy has had a significant effect on the royal family and British society.[1]

Early life

Diana Frances Spencer was born on 1 July 1961, the fourth of five children of John Spencer, Viscount Althorp (1924–1992), and Frances Spencer, Viscountess Althorp (née Roche; 1936–2004).[2] She was delivered at Park House, Sandringham, Norfolk.[3] The Spencer family had been closely allied with the British royal family for several generations;[4] her grandmothers, Cynthia Spencer, Countess Spencer, and Ruth Roche, Baroness Fermoy, had served as ladies-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.[5] Her parents were hoping for a boy to carry on the family line, and no name was chosen for a week until they settled on Diana Frances after her mother and Lady Diana Spencer, a many-times-great-aunt who was also a prospective Princess of Wales as a potential bride for Frederick, Prince of Wales.[6] Within the family, she was also known informally as "Duch", a reference to her duchess-like attitude in childhood.[7]

On 30 August 1961,[8] Diana was baptised at St. Mary Magdalene Church, Sandringham.[6] She grew up with three siblings: Sarah, Jane, and Charles.[9] Her infant brother, John, died shortly after his birth one year before Diana was born.[10] The desire for an heir added strain to her parents' marriage, and Lady Althorp was sent to Harley Street clinics in London to determine the cause of the "problem".[6] The experience was described as "humiliating" by Diana's younger brother, Charles: "It was a dreadful time for my parents and probably the root of their divorce because I don't think they ever got over it".[6] Diana grew up in Park House, situated on the Sandringham estate.[11] The family leased the house from its owner, Queen Elizabeth II, whom Diana called "Aunt Lilibet" since childhood.[12] The royal family frequently holidayed at the neighbouring Sandringham House, and Diana played with Princes Andrew and Edward.[13]

Diana was seven years old when her parents divorced.[14] Her mother later began a relationship with Peter Shand Kydd and married him in 1969.[15] Diana lived with her mother in London during her parents' separation in 1967, but during that year's Christmas holidays, Lord Althorp refused to let his daughter return to London with Lady Althorp. Shortly afterwards, he won custody of Diana with support from his former mother-in-law, Lady Fermoy.[16] In 1976, Lord Althorp married Raine, Countess of Dartmouth.[17] Diana's relationship with her stepmother was particularly bad.[18] She resented Raine, whom she called a "bully". On one occasion Diana pushed her down the stairs.[18] She later described her childhood as "very unhappy" and "very unstable, the whole thing".[19] She became known as Lady Diana after her father later inherited the title of Earl Spencer in 1975, at which point her father moved the entire family from Park House to Althorp, the Spencer seat in Northamptonshire.[20]

Education and career

Diana was initially home-schooled under the supervision of her governess, Gertrude Allen.[21] She began her formal education at Silfield Private School in King's Lynn, Norfolk, and moved to Riddlesworth Hall School, an all-girls boarding school near Thetford, when she was nine.[22] She joined her sisters at West Heath Girls' School in Sevenoaks, Kent, in 1973.[23] She did not perform well academically, failing her O-levels twice.[24][25] Her outstanding community spirit was recognised with an award from West Heath.[26] She left West Heath when she was sixteen.[27] Her brother Charles recalls her as being quite shy up until that time.[28] She demonstrated musical ability as a skilled pianist.[26] She also excelled in swimming and diving, and studied ballet and tap dance.[29]

In 1978 Diana worked for three months as a nanny for Philippa and Jeremy Whitaker in Hampshire.[30] After attending Institut Alpin Videmanette (a finishing school in Rougemont, Switzerland) for one term, and leaving after the Easter term of 1978,[31] Diana returned to London, where she shared her mother's flat with two school friends.[32] In London, she took an advanced cooking course and worked at a series of low-paying jobs; she worked as a dance instructor for youth until a skiing accident caused her to miss three months of work.[33] She then found employment as a playgroup pre-school assistant, did some cleaning work for her sister Sarah and several of her friends, and acted as a hostess at parties. She spent time working as a nanny for the Robertsons, an American family living in London,[34][35] and worked as a nursery teacher's assistant at the Young England School in Pimlico.[36] In July 1979, her mother bought her a flat at Coleherne Court in Earl's Court as an 18th birthday present.[37] She lived there with three flatmates until 25 February 1981.[38]

Personal life

Diana first met Charles, Prince of Wales, the Queen's eldest son and heir apparent, when she was 16 in November 1977. He was then 29 and dating her older sister, Sarah.[39][40] Charles and Diana were guests at a country weekend during the summer of 1980 and he took a serious interest in her as a potential bride.[41] The relationship progressed when he invited her aboard the royal yacht Britannia for a sailing weekend to Cowes. This was followed by an invitation to Balmoral Castle (the royal family's Scottish residence) to meet his family.[42][43] She was well received by the Queen, the Queen Mother and the Duke of Edinburgh. Charles subsequently courted Diana in London. He proposed on 6 February 1981 at Windsor Castle, and she accepted, but their engagement was kept secret for two and a half weeks.[38]

Engagement and wedding

Their engagement became official on 24 February 1981.[21] Diana selected her own engagement ring.[21] Following the engagement, she left her occupation as a nursery teacher's assistant and temporarily lived at the Queen Mother's residence, Clarence House.[44] She subsequently resided at Buckingham Palace until the wedding,[44] where, according to the biographer Ingrid Seward, her life was "incredibly lonely".[45] Diana was the first Englishwoman to marry the first in line to the throne since Anne Hyde married James, Duke of York and Albany (later James VII and II), over 300 years earlier, and she was also the first royal bride to have a paying job before her engagement.[21][26] Diana's first public appearance with Charles was at a charity ball held at Goldsmiths' Hall in March 1981, where she was introduced to Princess Grace of Monaco.[44]

Diana became Princess of Wales at age 20 when she married Charles, then 32, on 29 July 1981. The wedding was held at St Paul's Cathedral, which offered more seating than Westminster Abbey, a church that was generally used for royal weddings.[21][26] The service was widely described as a "fairytale wedding" and was watched by a global television audience of 750 million people while 600,000 spectators lined the streets to catch a glimpse of the couple en route to the ceremony.[21][46] At the altar, Diana inadvertently reversed the order of his first two names, saying "Philip Charles" Arthur George instead.[46] She did not say she would "obey" him; that traditional vow was left out at the couple's request, which caused some comment at the time.[47] Diana wore a dress valued at £9,000 (equivalent to £43,573 in 2023) with a 25-foot (7.62-metre) train.[48] Within a few years of the wedding, the Queen extended Diana visible tokens of membership in the royal family, lending her the Queen Mary's Lover's Knot Tiara[49][50] and granting her the badge of the Royal Family Order of Elizabeth II.[51][52]

Children

The couple had residences at Kensington Palace and Highgrove House, near Tetbury. On 5 November 1981, Diana's pregnancy was announced.[53] In January 1982—12 weeks into the pregnancy—Diana fell down a staircase at Sandringham, suffering some bruising, and the royal gynaecologist George Pinker was summoned from London; the foetus was uninjured.[54] Diana later confessed that she had intentionally thrown herself down the stairs because she was feeling "so inadequate".[55] On 21 June 1982, she gave birth to the couple's first son, Prince William.[56] She subsequently suffered from postpartum depression after her first pregnancy.[57] Amidst some media criticism, she decided to take William—who was still a baby—on her first major tours of Australia and New Zealand, and the decision was popularly applauded. By her own admission, Diana had not initially intended to take William until Malcolm Fraser, the Australian prime minister, made the suggestion.[58]

A second son, Harry, was born on 15 September 1984.[59] Diana said she and Charles were closest during her pregnancy with Harry.[60] She was aware their second child was a boy, but did not share the knowledge with anyone else, including Charles, who hoped for a girl.[61]

Diana gave her sons wider experiences than was usual for royal children.[21][62][63] She rarely deferred to Charles or to the royal family, and was often intransigent when it came to the children. She chose their first given names, dismissed a royal family nanny and engaged one of her own choosing, selected their schools and clothing, planned their outings, and took them to school herself as often as her schedule permitted. She also organised her public duties around their timetables.[64] Diana was reported to have described Harry as "naughty, just like me", and William as "my little wise old man" whom she started to rely on as her confidant by his early teens.[65]

Problems and separation

Five years into the marriage, the couple's incompatibility and age difference became visible and damaging.[66] In 1986, Diana began a relationship with James Hewitt, the family's former riding instructor and in the same year, Charles resumed his relationship with his former girlfriend Camilla Parker Bowles. The media speculated that Hewitt, not Charles, was Harry's father based on the alleged physical similarity between Hewitt and Harry, but Hewitt and others have denied this. Harry was born two years before Hewitt and Diana began their affair.[60][67]

By 1987, cracks in the marriage had become visible and the couple's unhappiness and cold attitude towards one another were being reported by the press,[45][68] who dubbed them "the Glums" because of their evident discomfort in each other's company.[69][70] In 1989, Diana was at a birthday party for Parker Bowles's sister, Annabel Elliot, when she confronted Parker Bowles about her and Charles's extramarital affair.[71][72] These affairs were later exposed in 1992 with the publication of Andrew Morton's book, Diana: Her True Story.[73][74] The book, which also revealed Diana's allegedly suicidal unhappiness, caused a media storm. In 1991, James Colthurst conducted secret interviews with Diana in which she had talked about her marital issues and difficulties. These recordings were later used as a source for Morton's book.[75][76] During her lifetime, both Diana and Morton denied her direct involvement in the writing process and maintained that family and friends were the book's main source; however, after her death Morton acknowledged Diana's role in writing the tell-all in the book's updated edition, Diana: Her True Story in Her Own Words.[77]

The Queen and Prince Philip hosted a meeting between Charles and Diana and unsuccessfully tried to effect a reconciliation.[78] Philip wrote to Diana and expressed his disappointment at the extramarital affairs of both her and Charles; he asked her to examine their behaviour from the other's point of view.[79] Diana reportedly found the letters difficult, but nevertheless appreciated that he was acting with good intent.[80] It was alleged by some people, including Diana's close friend Simone Simmons, that Diana and Philip had a tense relationship;[81][82][83] however, other observers said their letters provided no sign of friction between them.[84] Philip later issued a statement, publicly denying allegations of his insulting Diana.[85]

During 1992 and 1993, leaked tapes of telephone conversations reflected negatively on both Charles and Diana. Tape recordings of Diana and James Gilbey were made public in August 1992,[86] and transcripts were published the same month.[21] The article, "Squidgygate", was followed in November 1992 by the leaked "Camillagate" tapes, intimate exchanges between Charles and Parker Bowles, published in the tabloids.[87][88] In December 1992, Prime Minister John Major announced the couple's "amicable separation" to the House of Commons.[89][90]

Between 1992 and 1993, Diana hired a voice coach, Peter Settelen, to help her develop her public speaking voice.[91] In a videotape recorded by Settelen in 1992, Diana said that in 1984 through to 1986, she had been "deeply in love with someone who worked in this environment."[92][93] It is thought she was referring to Barry Mannakee,[94] who was transferred to the Diplomatic Protection Squad in 1986 after his managers had determined that his relationship with Diana had been inappropriate.[93][95] Diana said in the tape that Mannakee had been "chucked out" from his role as her bodyguard following suspicion that the two were having an affair.[92] Penny Junor suggested in her 1998 book that Diana was in a romantic relationship with Mannakee.[96] Diana's friends dismissed the claim as absurd.[96] In the subsequently released tapes, Diana said she had feelings for that "someone", saying "I was quite happy to give all this up [and] just to go off and live with him". She described him as "the greatest friend [she's] ever had", though she denied any sexual relationship with him.[97] She also spoke bitterly of her husband saying that "[He] made me feel so inadequate in every possible way, that each time I came up for air he pushed me down again."[98][99]

Although she blamed Parker Bowles for her marital troubles, Diana began to believe her husband had been involved in other affairs. In October 1993 Diana wrote to her butler Paul Burrell, telling him that she believed her husband was now in love with his personal assistant Tiggy Legge-Bourke—who was also his sons' former nanny—and was planning to have her killed "to make the path clear for him to marry Tiggy".[100][101] Legge-Bourke had been hired by Charles as a young companion for his sons while they were in his care, and Diana was resentful of Legge-Bourke and her relationship with the young princes.[102] Charles sought public understanding via a televised interview with Jonathan Dimbleby on 29 June 1994. In the interview, he said he had rekindled his relationship with Parker Bowles in 1986 only after his marriage to Diana had "irretrievably broken down".[103][104][105] In the same year, Diana's affair with Hewitt was exposed in detail in the book Princess in Love by Anna Pasternak, with Hewitt acting as the main source.[65] Diana was evidently disturbed and outraged when the book was released, although Pasternak claimed Hewitt had acted with Diana's support to avoid having the affair covered in Andrew Morton's second book.[65] In the same year, the News of the World claimed that Diana had had an affair with the married art dealer Oliver Hoare.[106][107] According to Hoare's obituary, there was little doubt she had been in a relationship with him.[108] However, Diana denied any romantic relationship with Hoare, whom she described as a friend.[109][110] She was also linked by the press to the rugby union player Will Carling[111][112] and private equity investor Theodore J. Forstmann,[113][114] yet these claims were neither confirmed nor proven.[115][116]

Divorce

The journalist Martin Bashir interviewed Diana for the BBC current affairs show Panorama. The interview was broadcast on 20 November 1995.[117] Diana discussed her own and her husband's extramarital affairs.[118] Referring to Charles's relationship with Parker Bowles, she said: "Well, there were three of us in this marriage, so it was a bit crowded." She also expressed doubt about her husband's suitability for kingship.[117] The authors Tina Brown, Sally Bedell Smith, and Sarah Bradford support Diana's admission in the interview that she had suffered from depression, bulimia and had engaged numerous times in the act of self-harm; the show's transcript records Diana confirming many of her mental health problems.[117] The combination of illnesses from which Diana herself said she suffered resulted in some of her biographers opining that she had borderline personality disorder.[119][120] It was later revealed that Bashir had used forged bank statements to win Diana and her brother's trust to secure the interview, falsely indicating people close to her had been paid for spying.[121] Lord Dyson conducted an independent inquiry into the issue and concluded that Bashir had "little difficulty in playing on [Diana's] fears and paranoia", a sentiment that was shared by Diana's son William.[122][123]

The interview proved to be the tipping point. On 20 December, Buckingham Palace announced that the Queen had sent letters to Charles and Diana, advising them to divorce.[124][125] The Queen's move was backed by Prime Minister John Major and by senior privy counsellors, and, according to the BBC, was decided after two weeks of talks.[126] Charles formally agreed to the divorce in a written statement soon after.[124] In February 1996, Diana announced her agreement after negotiations with Charles and representatives of the Queen,[127] irritating Buckingham Palace by issuing her own announcement of the divorce agreement and its terms. In July 1996, the couple agreed on the terms of their divorce.[128] This followed shortly after Diana's accusation that Charles's personal assistant Tiggy Legge-Bourke had aborted his child, after which Legge-Bourke instructed her solicitor Peter Carter-Ruck to demand an apology.[129][130] Diana's private secretary Patrick Jephson resigned shortly before the story broke, later writing that Diana had "exulted in accusing Legge-Bourke of having had an abortion".[131][132] The rumours of Legge-Bourke's alleged abortion were apparently spread by Martin Bashir as a means to gain his Panorama interview with Diana.[133]

The decree nisi was granted on 15 July 1996 and the divorce was finalised on 28 August 1996.[134][135] Diana was represented by Anthony Julius in the case.[136] The couple shared custody of their children.[137] She received a lump sum settlement of £17 million (equivalent to £40 million in 2023) as well as £400,000 per year. The couple signed a confidentiality agreement that prohibited them from discussing the details of the divorce or of their married life.[138][128] Days before, letters patent were issued with general rules to regulate royal titles after divorce. Diana lost the style "Her Royal Highness" and instead was styled Diana, Princess of Wales. As the mother of the prince expected to one day ascend to the throne, she was still considered to be a member of the royal family and was accorded the same precedence she enjoyed during her marriage.[139] The Queen reportedly wanted to let Diana continue to use the style of Royal Highness after her divorce, but Charles had insisted on removing it.[128] Prince William was reported to have reassured his mother: "Don't worry, Mummy, I will give it back to you one day when I am king".[140] Almost a year before, according to Tina Brown, Philip had warned Diana: "If you don't behave, my girl, we'll take your title away." She is said to have replied: "My title is a lot older than yours, Philip."[141]

Post-divorce

After her divorce, Diana retained the double apartment on the north side of Kensington Palace that she had shared with Charles since the first year of their marriage; the apartment remained her home until her death the following year. She also moved her offices to Kensington Palace but was permitted "to use the state apartments at St James's Palace".[128][142] In a book published in 2003, Paul Burrell claimed Diana's private letters had revealed that her brother, Lord Spencer, had refused to allow her to live at Althorp, despite her request.[130] The allegations were proven to be untrue as Spencer received legal apologies from different newspapers, including The Times in 2021, which admitted that "having considered his sister's safety, and in line with police advice, the Earl offered the Princess of Wales a number of properties including Wormleighton Manor, the Spencer family's original ancestral home".[143] However, he could not offer Garden House cottage on the Althorp estate to Diana as the home was intended for a member of staff.[143]

Diana was also given an allowance to run her private office, which was responsible for her charity work and royal duties, but from September 1996 onwards she was required to pay her bills and "any expenditure" incurred by her or on her behalf.[144] Furthermore, she continued to have access to the jewellery that she had received during her marriage, and was allowed to use the air transport of the British royal family and government.[128] Diana was also offered security by Metropolitan Police's Royalty Protection Group, which she benefitted from while travelling with her sons, but had refused it in the final years of her life, in an attempt to distance herself from the royal family.[145][146] After her death, it was revealed that Diana had been in discussion with Major's successor, Tony Blair, about a special role that would provide a government platform for her campaigns and charities to make her capable of endorsing Britain's interests overseas.[147]

Diana retained close friendships with several celebrities, including Elton John, Liza Minnelli, George Michael, Michael Jackson, and Gianni Versace, whose funeral she attended in 1997.[148][149] She dated the British-Pakistani heart surgeon Hasnat Khan, who was called "the love of her life" by many of her closest friends after her death,[150][151][152] and she is said to have described him as "Mr. Wonderful".[153][154][155][156] In May 1996, Diana visited Lahore upon invitation of Imran Khan, a relative of Hasnat Khan, and visited the latter's family in secret.[157][158] Khan was intensely private and the relationship was conducted in secrecy, with Diana lying to members of the press who questioned her about it. Their relationship lasted almost two years with differing accounts of who ended it.[158][159] She is said to have spoken of her distress when he ended their relationship.[150] However, according to Khan's testimony at the inquest into her death, it was Diana who ended their relationship in the summer of 1997.[160] Burrell also said the relationship was ended by Diana in July 1997.[81] Burrell also claimed that Diana's mother, Frances Shand Kydd, disapproved of her daughter's relationship with a Muslim man.[161] By the time of Diana's death in 1997, she had not spoken to her mother in four months.[162][163] By contrast, her relationship with her estranged stepmother had reportedly improved.[164][165]

Within a month, Diana began a relationship with Dodi Fayed, the son of her summer host, Mohamed Al-Fayed.[166] That summer, Diana had considered taking her sons on a holiday to the Hamptons on Long Island, New York, but security officials had prevented it. After deciding against a trip to Thailand, she accepted Fayed's invitation to join his family in the south of France, where his compound and large security detail would not cause concern to the Royal Protection squad. Mohamed Al-Fayed bought the Jonikal, a 60-metre multimillion-pound yacht on which to entertain Diana and her sons.[166][167][168] Tina Brown later claimed that Diana's romance with Fayed and her four-month relationship with Gulu Lalvani were a ploy "to inflame the true object of her affections, Hasnat Khan".[65] In the years after her death, Burrell, journalist Richard Kay, and voice coach Stewart Pierce have claimed that Diana was also thinking about buying a property in the United States.[169][170][171]

Princess of Wales

Following her engagement to Charles, Diana made her first official public appearance in March 1981 in a charity event at Goldsmiths' Hall.[172][173] She attended the Trooping the Colour for the first time in June 1981, making her appearance on the balcony of Buckingham Palace afterwards. In October 1981, Charles and Diana visited Wales.[26][174] She attended the State Opening of Parliament for the first time on 4 November 1981.[175] Her first solo engagement was a visit to Regent Street on 18 November 1981 to switch on the Christmas lights.[176] Diana made her inaugural overseas tour in September 1982, to attend the funeral of Princess Grace of Monaco.[26] Also in 1982, Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands created Diana a Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown.[177] In 1983, Diana accompanied Charles and William on a tour of Australia and New Zealand. The tour was a success and the couple drew immense crowds, though the press focused more on Diana rather than Charles, coining the term 'Dianamania' as a reference to people's obsession with her.[178] While sitting in a car with Charles near the Sydney Opera House, Diana burst into tears for a few minutes, which their office stated was due to jet lag and the heat.[179] In New Zealand, the couple met with representatives of the Māori people.[26] Their visit to Canada in June and July 1983 included a trip to Edmonton to open the 1983 Summer Universiade and a stop in Newfoundland to commemorate the 400th anniversary of that island's acquisition by the Crown.[180] In 1983, she was targeted by the Scottish National Liberation Army who tried to deliver a letter bomb to her.[181]

In February 1984, Diana was the patron of London City Ballet when she travelled to Norway on her own to attend a performance organised by the company.[26] In April 1985, Charles and Diana visited Italy, and were later joined by their sons.[26] They met with President Alessandro Pertini. Their visit to the Holy See included a private audience with Pope John Paul II.[182] In autumn 1985, they returned to Australia, and their tour was well received by the public and the media, who referred to Diana as "Di-amond Princess" and the "Jewel in the Crown".[183] In November 1985, the couple visited the United States,[26] meeting Ronald and Nancy Reagan at the White House. Diana had a busy year in 1986 as she and Charles toured Japan, Spain, and Canada.[180] In Canada, they visited Expo 86,[180] where Diana fainted in the California Pavilion.[184][185] In November 1986, she went on a six-day tour to Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, where she met King Fahd of Saudi Arabia and Sultan Qaboos of Oman.[186]

In 1988, Charles and Diana visited Thailand and toured Australia for the bicentenary celebrations.[26][187] In February 1989, she spent a few days in New York as a solo visit, mainly to promote the works of the Welsh National Opera, of which she was a patron.[188] During a tour of Harlem Hospital Center, she spontaneously hugged a seven-year-old child with AIDS.[189] In March 1989, she had her second trip to the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, in which she visited Kuwait and the UAE.[186]

In March 1990, Diana and Charles toured Nigeria and Cameroon.[190] The president of Cameroon hosted an official dinner to welcome them in Yaoundé.[190] Highlights of the tour included visits by Diana to hospitals and projects focusing on women's development.[190] In May 1990, they visited Hungary for four days.[189][191] It was the first visit by members of the royal family to "a former Warsaw Pact country".[189] They attended a dinner hosted by President Árpád Göncz and viewed a fashion display at the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest.[191] Peto Institute was among the places visited by Diana, and she presented its director with an honorary OBE.[189] In November 1990, she and Charles went to Japan to attend the enthronement of Emperor Akihito.[26][192]

In her desire to play an encouraging role during the Gulf War, Diana visited Germany in December 1990 to meet with the families of soldiers.[189] She subsequently travelled to Germany in January 1991 to visit RAF Bruggen, and later wrote an encouraging letter which was published in Soldier, Navy News and RAF News.[189] In 1991, Charles and Diana visited Queen's University at Kingston, Ontario, where they presented the university with a replica of their royal charter.[193] In September 1991, Diana visited Pakistan on a solo trip, and went to Brazil with Charles.[194] During the Brazilian tour, Diana paid visits to organisations that battled homelessness among street children.[194] Her final trips with Charles were to India and South Korea in 1992.[26] She visited Mother Teresa's hospice in Kolkata, India.[195] The two women met later in the same month in Rome[196] and developed a personal relationship.[195] It was also during the Indian tour that pictures of Diana alone in front of the Taj Mahal made headlines.[197][198][199] In May 1992, she went on a solo tour of Egypt, visiting the Giza pyramid complex and attending a meeting with Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.[200][201] In November 1992, she went on an official solo trip to France and had an audience with President François Mitterrand.[202] In March 1993, she went on her first solo trip after her separation from Charles, visiting a leprosy hospital in Nepal where she met and came into contact with some patients, marking the first time they had ever been touched by a dignitary who had come to visit.[203] In December 1993, she announced that she would withdraw from public life, but in November 1994 she said she wished to "make a partial return".[26][189] In her capacity as the vice-president of British Red Cross, she was interested in playing an important role for its 125th anniversary celebrations.[189] Later, the Queen formally invited her to attend the anniversary celebrations of D-Day.[26] In February 1995, Diana visited Japan.[192] She paid a formal visit to Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko,[192] and visited the National Children's Hospital in Tokyo.[204] In June 1995, Diana went to the Venice Biennale art festival,[205] and also visited Moscow where she received the International Leonardo Prize.[206] In November 1995, Diana undertook a four-day trip to Argentina to attend a charity event.[207] She visited many other countries, including Belgium, Switzerland, and Zimbabwe, alongside numerous others.[26] During her separation from Charles, which lasted for almost four years, Diana participated in major national occasions as a senior member of the royal family, notably including "the commemorations of the 50th anniversaries of Victory in Europe Day and Victory over Japan Day" in 1995.[26]

Charity work and patronages

In 1983 Diana confided to the premier of Newfoundland, Brian Peckford, "I am finding it very difficult to cope with the pressures of being Princess of Wales, but I am learning to cope with it".[208] She was expected to make regular public appearances at hospitals, schools, and other facilities, in the 20th-century model of royal patronage. From the mid-1980s, she became increasingly associated with numerous charities. She carried out 191 official engagements in 1988[209] and 397 in 1991.[210] Diana developed an intense interest in serious illnesses and health-related matters outside the purview of traditional royal involvement, including AIDS and leprosy. In recognition of her effect as a philanthropist, Stephen Lee, director of the UK Institute of Charity Fundraising Managers, said "Her overall effect on charity is probably more significant than any other person's in the 20th century."[211]

Diana was the patroness of charities and organisations who worked with the homeless, youth, drug addicts, and the elderly. From 1989, she was president of Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children. She was patron of the Natural History Museum[212][213] and president of the Royal Academy of Music[129][214][212] and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.[215] From 1984 to 1996, she was president of Barnardo's, a charity founded by Dr. Thomas John Barnardo in 1866 to care for vulnerable children and young people.[216][212] In 1988, she became patron of the British Red Cross and supported its organisations in other countries such as Australia and Canada.[189] She made several lengthy visits each week to Royal Brompton Hospital, where she worked to comfort seriously ill or dying patients.[195] From 1991 to 1996, she was a patron of Headway, a brain injury association.[212][217] In 1992, she became the first patron of Chester Childbirth Appeal, a charity she had supported since 1984.[218] The charity, which is named after one of Diana's royal titles, could raise over £1 million with her help.[218] In 1994, she helped her friend Julia Samuel launch the charity Child Bereavement UK which supports children "of military families, those of suicide victims, [and] terminally-ill parents", and became its patron.[219] Her son William later became the charity's royal patron.[220][a]

In 1987 Diana was awarded the Honorary Freedom of the City of London, the highest honour which is in the power of the City of London to bestow on someone.[225][226] In June 1995, she travelled to Moscow. She paid a visit to a children's hospital she had previously supported when she provided them with medical equipment. In December 1995, Diana received the United Cerebral Palsy Humanitarian of the Year Award in New York City for her philanthropic efforts.[227][228][229] In October 1996, for her works on the elderly, she was awarded a gold medal at a health care conference organised by the Pio Manzù Centre in Rimini, Italy.[230]

The day after her divorce, she announced her resignation from over 100 charities and retained patronages of only six: Centrepoint, English National Ballet, Great Ormond Street Hospital, The Leprosy Mission, National AIDS Trust, and the Royal Marsden Hospital.[231] She continued her work with the British Red Cross Anti-Personnel Land Mines Campaign, but was no longer listed as patron.[232][233]

In May 1997, Diana opened the Richard Attenborough Centre for Disability and the Arts in Leicester, after being asked by her friend Richard Attenborough.[234] In June 1997 and at the suggestion of her son William, some of her dresses and suits were sold at Christie's auction houses in London and New York, and the proceeds that were earned from these events were donated to charities.[26] Her final official engagement was a visit to Northwick Park Hospital, London, on 21 July 1997.[26] Her 36th and final birthday celebration was held at Tate Gallery, which was also a commemorative event for the gallery's 100th anniversary.[26] She was scheduled to attend a fundraiser at the Osteopathic Centre for Children on 4 September 1997, upon her return from Paris.[235]

HIV/AIDS

Diana began her work with AIDS patients in the 1980s.[236] Contrary to the prevailing stigmatization of AIDS patients, she was not averse to making physical contact with patients,[195] and was the first British royal to do so.[236] In 1987, she held hands with an AIDS patient in one of her early efforts to destigmatise the condition.[237][238] Diana noted: "HIV does not make people dangerous to know. You can shake their hands and give them a hug. Heaven knows they need it. What's more, you can share their homes, their workplaces, and their playgrounds and toys".[189] To Diana's disappointment, the Queen did not support this type of charity work, suggesting she get involved in "something more pleasant".[236] In July 1989, she opened Landmark Aids Centre in South London.[239][240] In October 1990, Diana opened Grandma's House, a home for young AIDS patients in Washington, DC.[241] She was also a patron of the National AIDS Trust and regularly visited London Lighthouse, which provided residential care for HIV patients (it has since merged with the Terrence Higgins Trust).[189][242] In 1991, she hugged one patient during a visit to the AIDS ward of the Middlesex Hospital,[189] which she had opened in 1987 as the first hospital unit dedicated to this cause in the UK.[237][243] As the patron of Turning Point, a health and social care organisation, Diana visited its project in London for people with HIV/AIDS in 1992.[244] She later established and led fundraising campaigns for AIDS research.[21]

In March 1997, Diana visited South Africa, where she met with Nelson Mandela.[245][246] On 2 November 2002, Mandela announced that the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund would be teaming up with the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund to help people with AIDS.[247] They had planned the combination of the two charities a few months before her death.[247] Mandela later praised Diana for her efforts surrounding the issue of HIV/AIDS: "When she stroked the limbs of someone with leprosy or sat on the bed of a man with HIV/AIDS and held his hand, she transformed public attitudes and improved the life chances of such people".[248] Diana had used her celebrity status to "fight stigma attached to people living with HIV/AIDS", Mandela said.[247]

Landmines

Diana was patron of the HALO Trust, an organisation that removes debris—particularly landmines—left behind by war.[249][250] In January 1997, pictures of Diana touring an Angolan minefield in a ballistic helmet and flak jacket were seen worldwide.[249][250] During her campaign, she was accused of meddling in politics and called a "loose cannon" by Lord Howe, an official in the British Ministry of Defence.[251] Despite the criticism, HALO states that Diana's efforts resulted in raising international awareness about landmines and the subsequent sufferings caused by them.[249][250] In June 1997, she gave a speech at a landmines conference held at the Royal Geographical Society, and went to Washington, DC to support the American Red Cross's anti-landmine initiative.[26] From 7 to 10 August 1997, just days before her death, she visited Bosnia and Herzegovina with Jerry White and Ken Rutherford of the Landmine Survivors Network.[26][252][253][254]

Diana's work on the landmines issue has been described as influential in the signing of the Ottawa Treaty, which created an international ban on the use of anti-personnel landmines.[255] Introducing the Second Reading of the Landmines Bill 1998 to the British House of Commons, the Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, paid tribute to Diana's work on landmines:

All Honourable Members will be aware from their postbags of the immense contribution made by Diana, Princess of Wales to bringing home to many of our constituents the human costs of landmines. The best way in which to record our appreciation of her work, and the work of NGOs that have campaigned against landmines, is to pass the Bill, and to pave the way towards a global ban on landmines.[256]

A few months after Diana's death in 1997, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines won the Nobel Peace Prize.[257]

Cancer

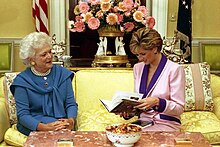

For her first solo official trip, Diana visited The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, a cancer treatment hospital in London.[222] She later chose this charity to be among the organisations that benefited from the auction of her clothes in New York.[222] The trust's communications manager said she did "much to remove the stigma and taboo associated with diseases such as cancer, AIDS, HIV and leprosy".[222] Diana became president of the hospital on 27 June 1989.[258][259][260] The Wolfson Children's Cancer Unit was opened by Diana on 25 February 1993.[258] In February 1996, Diana, who had been informed about a newly opened cancer hospital built by Imran Khan, travelled to Pakistan to visit its children's cancer wards and attend a fundraising dinner in aid of the charity in Lahore.[261] She later visited the hospital again in May 1997.[262] In June 1996, she travelled to Chicago in her capacity as president of the Royal Marsden Hospital in order to attend a fundraising event at the Field Museum of Natural History and raised more than £1 million for cancer research.[189] She additionally visited patients at the Cook County Hospital and delivered remarks at a conference on breast cancer at the Northwestern University Chicago campus after meeting a group of breast cancer researchers.[263] In September 1996, after being asked by Katharine Graham, Diana went to Washington and appeared at a White House breakfast in respect of the Nina Hyde Center for Breast Cancer Research.[264] She also attended an annual fund-raiser for breast cancer research organised by The Washington Post at the same centre.[21][265]

In 1988, Diana opened Children with Leukaemia (later renamed Children with Cancer UK) in memory of two young cancer victims.[266][267][268] In November 1987, a few days after the death of Jean O'Gorman from cancer, Diana met her family.[266][267] The deaths of Jean and her brother affected her and she assisted their family to establish the charity.[266][267][268] It was opened by her on 12 January 1988 at Mill Hill Secondary School, and she supported it until her death in 1997.[266][268]

Other areas

In November 1989, Diana visited a leprosy hospital in Indonesia.[269][236] Following her visit, she became patron of the Leprosy Mission, an organisation dedicated to providing medicine, treatment, and other support services to those who are afflicted with the disease. She remained the patron of this charity[231] and visited several of its hospitals around the world, especially in India, Nepal, Zimbabwe and Nigeria until her death in 1997.[189][270] She touched those affected by the disease when many people believed it could be contracted through casual contact.[189][269] "It has always been my concern to touch people with leprosy, trying to show in a simple action that they are not reviled, nor are we repulsed", she commented.[270] The Diana Princess of Wales Health Education and Media Centre in Noida, India, was opened in her honour in November 1999, funded by the Diana Princess of Wales Memorial Fund to give social support to the people affected by leprosy and disability.[270]

Diana was a long-standing and active supporter of Centrepoint, a charity which provides accommodation and support to homeless people, and became patron in 1992.[271][272] She supported organisations that battle poverty and homelessness, including the Passage.[273] Diana was a supporter of young homeless people and spoke out on behalf of them by saying that "they deserve a decent start in life".[274] "We, as a part of society, must ensure that young people—who are our future—are given the chance they deserve", she said.[274] Diana used to take young William and Harry for private visits to Centrepoint services and homeless shelters.[21][271][275] "The young people at Centrepoint were always really touched by her visits and by her genuine feelings for them", said one of the charity's staff members.[276] William later became the patron of Centrepoint.[271]

Diana was a staunch and longtime supporter of charities and organisations that focused on social and mental issues, including Relate and Turning Point.[189] Relate was relaunched in 1987 as a renewed version to its predecessor, the National Marriage Guidance Council. Diana became its patron in 1989.[189] Turning Point, a health and social care organisation, was founded in 1964 to help and support those affected by drug and alcohol misuse and mental health problems. She became the charity's patron in 1987 and visited the charity on a regular basis, meeting the sufferers at its centres or institutions including Rampton and Broadmoor.[189] In 1990 during a speech for Turning Point she said, "It takes professionalism to convince a doubting public that it should accept back into its midst many of those diagnosed as psychotics, neurotics and other sufferers who Victorian communities decided should be kept out of sight in the safety of mental institutions".[189] Despite the protocol problems of travelling to a Muslim country, she made a trip to Pakistan in 1991 in order to visit a rehabilitation centre in Lahore as a sign of "her commitment to working against drug abuse".[189]

Privacy and legal issues

In November 1980, the Sunday Mirror ran a story claiming that Charles had used the Royal Train twice for secret love rendezvous with Diana, prompting the palace to issue a statement, calling the story "a total fabrication" and demanding an apology.[277][278] The newspaper editors, however, insisted that the woman boarding the train was Diana and declined to apologise.[277] In February 1982, pictures of a pregnant Diana in bikini while holidaying were published in the media. The Queen subsequently released a statement and called it "the blackest day in the history of British journalism."[279]

In 1993 Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN) published photographs of Diana that were taken by gym owner Bryce Taylor. The photos showed her exercising in the gym LA Fitness wearing "a leotard and cycling shorts".[280][281] Diana's lawyers immediately filed a criminal complaint that sought "a permanent ban on the sale and publication of the photographs" around the world.[280][281] However, some newspapers outside the UK published the pictures.[280] The courts granted an injunction against Taylor and MGN that prohibited "further publication of the pictures".[280] MGN later issued an apology after facing much criticism from the public and gave Diana £1 million as a payment for her legal costs, while donating £200,000 to her charities.[280] LA Fitness issued its own apology in June 1994, which was followed by Taylor apologising in February 1995 and giving up the £300,000 he had made from the sale of pictures in an out-of-court settlement about a week before the case was set to start.[280] It was alleged that a member of the royal family had helped him financially to settle out of court.[280]

In 1994 pictures of Diana sunbathing topless at a Costa del Sol hotel were put up for sale by a Spanish photography agency for a price of £1 million.[282] In 1996, a set of pictures of a topless Diana while sunbathing appeared in the Mirror, which resulted in "a furor about invasion of privacy".[65] In the same year, she was the subject of a hoax call by Victor Lewis-Smith, who pretended to be Stephen Hawking, though the full recorded conversation was never released.[283] Also in 1996, Stuart Higgins of The Sun wrote a front-page story about an intimate video purporting to feature Diana with James Hewitt. The video turned out to be a hoax, forcing Higgins to issue an apology.[284][285]

Death

Diana died on 31 August 1997 in a car crash in the Pont de l'Alma tunnel in Paris while her driver was fleeing the paparazzi.[286] The crash also resulted in the deaths of her companion Dodi Fayed and their driver, Henri Paul, who was also the acting security manager of Hôtel Ritz Paris. Trevor Rees-Jones, who was employed as a bodyguard by Dodi's father,[287] survived the crash, suffering a serious head injury. The televised funeral, on 6 September, was watched by a British television audience that peaked at 32.1 million, which was one of the United Kingdom's highest viewing figures ever and a United States television audience that peaked at 50 million.[288][289] The event was broadcast to over 200 countries and was seen by an estimated 2.5 billion people.[290][291]

Tribute, funeral, and burial

The sudden and unexpected death of an extraordinarily popular royal figure brought statements from senior figures worldwide and many tributes by members of the public.[292][293][294] People left flowers, candles, cards, and personal messages outside Kensington Palace for many months. Diana's coffin, draped with the royal flag, was brought to London from Paris by Charles and her two sisters on 31 August 1997.[295][296] The coffin was taken to a private mortuary and then placed in the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace.[295]

On 5 September, Queen Elizabeth II paid tribute to Diana in a live television broadcast.[26] The funeral took place in Westminster Abbey on 6 September. Her sons walked in the funeral procession behind her coffin, along with the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Edinburgh, Diana's brother Lord Spencer, and representatives of some of her charities.[26] Lord Spencer said of his sister, "She proved in the last year that she needed no royal title to continue to generate her particular brand of magic."[297] Re-written in tribute to Diana, "Candle in the Wind 1997" was performed by Elton John at the funeral service (the only occasion the song has been performed live).[298] Released as a single in 1997, the global proceeds from the song have gone to Diana's charities.[298][299][300]

The burial took place privately later the same day. Diana's former husband, sons, mother, siblings, a close friend, and a clergyman were present. Diana's body was clothed in a black long-sleeved dress designed by Catherine Walker, which she had chosen some weeks before. A set of rosary beads that she had received from Mother Teresa was placed in her hands. Diana's grave is on an island within the grounds of Althorp Park, the Spencer family home for centuries.[301]

The burial party was provided by the 2nd Battalion the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment, who carried Diana's coffin across to the island and laid her to rest. Diana was the Regiment's Colonel-in-Chief from 1992 to 1996.[302] The original plan was for Diana to be buried in the Spencer family vault at the local church in nearby Great Brington, but Lord Spencer said he was concerned about public safety and security and the onslaught of visitors that might overwhelm Great Brington. He decided Diana would be buried where her grave could be easily cared for and visited in privacy by William, Harry, and other relatives.[303]

Conspiracy theories, inquest and verdict

The initial French judicial investigation concluded that the crash was caused by Paul's intoxication, reckless driving, speeding, and effects of prescription drugs.[304] In February 1998, Mohamed Al-Fayed, father of Dodi Fayed, publicly said the crash, which killed his son, had been planned,[305] and accused MI6 and the Duke of Edinburgh.[306] An inquest, which started in London in 2004 and continued in 2007 and 2008,[307] attributed the crash to grossly negligent driving by Paul and to the pursuing paparazzi, who forced Paul to speed into the tunnel.[308] On 7 April 2008, the jury returned a verdict of "unlawful killing". On the day after the final verdict of the inquest, Al-Fayed announced that he would end his 10-year campaign to establish that the tragedy was murder; he said he did so for the sake of Diana's children.[309]

Later events

Finances

Following her death, Diana left a £21 million estate, "netting £17 million after estate taxes", which were left in the hands of trustees, her mother, and her sister Sarah.[310][311] The will was signed in June 1993, but Diana had it modified in February 1996 to remove the name of her personal secretary from the list of trustees and have Sarah replace him.[312] After applying personal and inheritance taxes, a net estate of £12.9 million was left to be distributed among the beneficiaries.[313] Her two sons subsequently inherited the majority of her estate. Each of them was left with £6.5 million which was invested and gathered substantial interest, and an estimated £10 million was given to each son upon turning 30 years old in 2012 and 2014 respectively.[314][315] Many of Diana's possessions were initially left in the care of her brother, who put them on show in Althorp twice a year until they were returned to Diana's sons.[314][310] They were also put on display in American museums and as of 2011[update] raised two million dollars for charities.[310] Among the objects were her dresses and suits along with numerous family paintings and jewels.[314] Diana's engagement ring and her yellow gold watch were given to William and Harry, respectively. William later passed the ring to his wife, Catherine Middleton. Her wedding dress was also given to her sons.[314][316][317]

In addition to her will,[311] Diana had also written a letter of wishes in which she had asked for three-quarters of her personal property to be given to her sons, and dividing the remaining quarter (aside from the jewellery) among her 17 godchildren.[310] Despite Diana's wishes, the executors (her mother and sister) "petitioned the probate court for a "variance" of the will", and the letter of wishes was ignored "because it did not contain certain language required by British law".[310] Eventually, one item from Diana's estate was given to each of her godchildren, while they would have received £100,000 each if a quarter of her estate had been divided between them.[310] The variance also delayed the distribution of her estate to her sons until they reached age 30. (It had originally been set at age 25.)[310][311] Diana also left her butler Paul Burrell around £50,000 in cash.[313][311]

Subject of US government surveillance

In 1999, after the submission of a Freedom of Information request by the Internet news service apbonline.com, it was revealed that Diana had been placed under surveillance by the National Security Agency until her death, and the organisation kept a top secret file on her containing more than 1,000 pages.[318][319] The contents of Diana's NSA file cannot be disclosed because of national security concerns.[318] The NSA officials insisted Diana was not a "target of [their] massive, worldwide electronic eavesdropping infrastructure."[318] Despite multiple inquiries for the files to be declassified—with one of the notable ones being filed by Mohamed Al-Fayed—the NSA has refused to release the documents.[319]

In 2008, Ken Wharfe, a former bodyguard of Diana, claimed that her scandalous conversations with James Gilbey (commonly referred to as Squidgygate) were in fact recorded by the GCHQ, which intentionally released them on a "loop".[320] People close to Diana believed the action was intended to defame her.[320] Wharfe said Diana herself believed that members of the royal family were all being monitored, though he also stated that the main reason for it could be the potential threats of the IRA.[320]

Anniversaries, commemorations, and auctions

On the first anniversary of Diana's death, people left flowers and bouquets outside the gates of Kensington Palace and a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey.[321][322] The royal family and Tony Blair and his family went to Crathie Kirk for private prayers, while Diana's family held a private memorial service at Althorp.[323][324] All flags at Buckingham Palace and other royal residences were flown at half-mast on the Queen's orders.[325] The Union Jack was first lowered to half-mast on the day of Diana's funeral and has set a precedent, as based on the previous protocol no flag could ever fly at half-mast over the palace "even on the death of a monarch".[325] Since 1997, however, the Union Flag (but not the Royal Standard) has flown at half-mast upon the deaths of members of the royal family, and other times of national mourning.[326]

The Concert for Diana at Wembley Stadium was held on 1 July 2007. The event, organised by Princes William and Harry, celebrated the 46th anniversary of their mother's birth and occurred a few weeks before the 10th anniversary of her death on 31 August.[327][328] The proceeds from this event were donated to Diana's charities.[329] On 31 August 2007, a service of thanksgiving for Diana took place in the Guards' Chapel.[330] Among the 500 guests were members of the royal family and their relatives, members of the Spencer family, her godparents and godchildren, members of her wedding party, her close friends and aides, representatives from many of her charities, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and John Major, and friends from the entertainment world such as David Frost, Elton John, and Cliff Richard.[214][331]

In January 2017, a series of letters that Diana and other members of the royal family had written to a Buckingham Palace steward were sold as a part of a collection.[332][333] The six letters written by Diana raised £15,100.[332][333] Another collection of 40 letters written by Diana between 1990 and 1997 were sold for £67,900 at an auction in 2021.[334] In 2023, two of Diana's friends put 32 highly personal letters and cards written by her while she was going through her divorce up for auction, announcing that proceeds of the sale would be donated to charities associated with them or Diana.[335]

"Diana: Her Fashion Story", an exhibition of gowns and suits worn by Diana, was announced to be opened at Kensington Palace in February 2017 as a tribute to mark her 20th death anniversary, with her favourite dresses created by numerous fashion designers being displayed until the next year.[336][337][338][339] Other tributes planned for the anniversary included exhibitions at Althorp hosted by Diana's brother, Earl Spencer,[340] a series of commemorating events organised by the Diana Award,[341] as well as restyling Kensington Gardens and creating a new section called "The White Garden".[336][337][342]

Legacy

Public image

Diana remains one of the most popular members of the royal family throughout history, and she continues to influence the younger generations of royals.[343][344][345] She was a major presence on the world stage from her engagement to Charles until her death, and was often described as the "world's most photographed woman".[21][346] She was noted for her compassion, style, charisma, and high-profile charity work, as well as her ill-fated marriage.[347][211][348] Biographer Sarah Bradford commented, "The only cure for her suffering would have been the love of the Prince of Wales ... the way in which he consistently denigrated her reduced her to despair."[99] Despite all the marital issues and scandals, Diana continued to enjoy a high level of popularity in the polls while her husband was suffering from low levels of public approval.[21] Diana's former private secretary Patrick Jephson described her as an organised and hardworking person, and pointed out Charles was not able to "reconcile with his wife's extraordinary popularity",[349] a viewpoint supported by the biographer Tina Brown.[350] He also said she was a tough boss who was "equally quick to appreciate hard work" but could also be defiant "if she felt she had been the victim of injustice".[349] Diana's mother also defined her as a "loving" figure who could occasionally be "tempestuous".[162] She was often described as a devoted mother to her children,[21][351] who are believed to be influenced by her personality and way of life.[352]

In the early years, Diana was often noted for her shy nature.[344][353] Journalist Michael White perceived her as being "smart", "shrewd and funny".[345] Those who communicated with her closely described her as a person who was led by "her heart".[21] In an article for The Guardian, Monica Ali believed that, despite being inexperienced and uneducated, Diana could handle the expectations of the royal family and overcome the difficulties and sufferings of her marital life. Ali also believed that she "had a lasting influence on the public discourse, particularly in matters of mental health" by discussing her eating disorder publicly.[211] According to Tina Brown, in her early years Diana possessed a "passive power", a quality that in her opinion she shared with the Queen Mother and a trait that would enable her to instinctively use her appeal to achieve her goals.[354]

Diana was known for her encounters with sick and dying patients, and the poor and unwanted whom she used to comfort, an action that earned her more popularity.[355] Known for her easygoing attitude, she reportedly hated formality in her inner circle, asking "people not to jump up every time she enters the room".[356] Diana is often credited with widening the range of charity works carried out by the royal family in a more modern style.[211] Eugene Robinson of The Washington Post wrote in an article that "Diana imbued her role as royal princess with vitality, activism and, above all, glamour."[21] Alicia Carroll of The New York Times described Diana as "a breath of fresh air" who was the main reason the royal family was known in the United States.[357] In Anthony Holden's opinion, Diana was "visibly reborn" after her separation from Charles, a point in her life that was described by Holden as her "moment of triumph", which put her on an independent path to success.[202]

Diana's sudden death brought an unprecedented spasm of grief and mourning,[358] and subsequently a crisis arose in the Royal Household.[359][360][361] Andrew Marr said that by her death she "revived the culture of public sentiment".[211] Her son William has stated that the outpouring of public grief after her death "changed the British psyche, for the better", while Alastair Campbell noted that it assisted in diminishing "the stiff upper lip approach".[362] In 1997 Diana was one of the runners-up for Time magazine's Person of the Year,[363] and in 2020 the magazine included Diana's name on its list of 100 Women of the Year. She was chosen as the Woman of the Year 1987 for her efforts in destigmatising the conditions surrounding HIV/AIDS patients.[364] In 2002 Diana ranked third on the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons, above the Queen and other British monarchs.[365]

Despite being regarded as an iconic figure and a popular member of the royal family, Diana was subject to criticism during her life.[344] She was criticised by philosophy professor Anthony O'Hear who in his notes argued that she was unable to fulfill her duties, her reckless behaviour was damaging the monarchy, and she was "self-indulgent" in her philanthropic efforts.[276] Following his remarks, charity organisations that were supported by Diana defended her, and Peter Luff called O'Hear's comments "distasteful and inappropriate".[276] Further criticism surfaced as she was accused of using her public profile to benefit herself,[120] which in return "demeaned her royal office".[344] Diana's unique type of charity work, which sometimes included physical contact with people affected by serious diseases, occasionally had a negative reaction in the media.[344]

Diana's relationship with the press and the paparazzi has been described as "ambivalent". On different occasions she would complain about the way she was being treated by the media, mentioning that their constant presence in her proximity had made life impossible for her, whereas at other times she would seek their attention and hand information to reporters herself.[366][367] Writing for The Guardian, Peter Conrad suggested that it was Diana who let the journalists and paparazzi into her life as she knew they were the source of her power.[368] This view was supported by Christopher Hitchens, who believed that "in pursuit of a personal solution to an unhappy private life, she became an assiduous leaker to the press".[369] Tina Brown argued that Diana was in no way "a vulnerable victim of media manipulation", and she found it "offensive to present the canny, resourceful Diana as a woman of no agency".[65] Former News of the World royal editor Clive Goodman, who later hacked the phones of Diana's sons on several occasions, stated in a court in 2014 that in 1992 Diana sent a confidential directory which contained numbers of senior members of the royal household to their office to get back at Prince Charles.[370] Nevertheless, Diana also used the media's interest in her to shine light on her charitable efforts and patronages.[366]

Sally Bedell Smith characterised Diana as unpredictable, egocentric, and possessive.[120] Smith also argued that in her desire to do charity works, Diana was "motivated by personal considerations, rather than by an ambitious urge to take on a societal problem".[120] Eugene Robinson, however, said that "[Diana] was serious about the causes she espoused".[21] According to Sarah Bradford, Diana looked down on the House of Windsor, whom she reportedly viewed "as jumped-up foreign princelings" and called them "the Germans".[368] Tony Blair characterised Diana as a manipulative person and "extraordinarily captivating".[345][359][371]

In an article written for The Independent in 1998, journalist Yvonne Roberts observed the sudden change in people's opinion of Diana after her death from critical to complimentary, a viewpoint supported by Theodore Dalrymple, who also noticed the "sudden shift".[372] Roberts also added that Diana was neither "a saint" nor "a revolutionary" figure, but "may have encouraged some people" to tackle issues such as landmines, AIDS and leprosy.[373] While analysing the impact of Diana's death and her popularity from a gendered point of view, the British historian Ludmilla Jordanova said "no human being can survive the complex forces that impact upon charismatic women." Jordanova also observed that it is "Better to remember her by trying to decipher how emotions overshadow analysis and why women are the safeguards of humanitarian feelings."[348] The author Anne Applebaum believed that Diana had not had any impact on public opinions posthumously;[211] an idea supported by Jonathan Freedland of The Guardian who believed that Diana's memory and influence started to fade away in the years after her death,[374] while Peter Conrad, another Guardian contributor, argued that even in "a decade after her death, she is still not silent",[368] and Allan Massie of The Telegraph believed that Diana's sentiments "continue to shape our society".[375] Writing for The Guardian, Monica Ali described Diana as "fascinating and flawed. Her legacy might be mixed, but it's not insubstantial. Her life was brief, but she left her mark".[211]

Fashion and style

Diana was a fashion icon whose style was emulated by women around the world. In 2012, Time included Diana on its All-Time 100 Fashion Icons list.[376] Iain Hollingshead of The Telegraph wrote: "[Diana] had an ability to sell clothes just by looking at them."[377][378] An early example of the effect occurred during her courtship with Charles in 1980 when sales of Hunter Wellington boots skyrocketed after she was pictured wearing a pair on the Balmoral estate.[377][379] According to designers and people who worked with Diana, she used fashion and style to endorse her charitable causes, express herself and communicate.[380][381][382] Diana remains a prominent figure for her fashion style, impacting recent cultural and style trends.[383][384][336][385]

Diana's fashion combined classically royal expectations with contemporary fashion trends in Britain.[386][387] While on diplomatic trips, her clothes and attire were chosen to match the destination countries' costumes, and while off-duty she used to wear loose jackets and jumpers.[384][388] "She was always very thoughtful about how her clothes would be interpreted, it was something that really mattered to her", according to Anna Harvey, a former British Vogue editor and Diana's fashion mentor.[384][389] Her fashion sense originally incorporated decorous and romantic elements, with pastel shades and lush gowns.[387][390][391] Elements of her fashion rapidly became trends.[384] She forwent certain traditions, such as wearing gloves during engagements, and sought to create a wardrobe that helped her to connect with the public.[382][388] According to Donatella Versace who worked closely with Diana alongside her brother, Diana's interest and sense of curiosity about fashion grew significantly after her marital separation.[380] Her style subsequently grew bolder and more businesslike, featuring structured skirt suits, sculptural gowns, and neutral tones designed to reflect attention toward her charity work.[383][392]

Catherine Walker was among Diana's favourite designers[387] with whom she worked to create her "royal uniform".[393] Among her favoured designers were Versace, Armani, Chanel, Dior, Gucci and Clarks.[384][385][394] Her famous outfits include the "Black Sheep Sweater",[395][396] the "Revenge dress", which she wore after Charles's admission of adultery,[397] and the "Travolta dress".[384][393][387] Copies of Diana's British Vogue-featured pink chiffon blouse by David and Elizabeth Emanuel, which appeared in the magazine on her engagement announcement day, sold in the millions.[387] She appeared on three British Vogue covers during her lifetime and was featured on its October 1997 issue posthumously.[398] Diana did her own makeup for events, and was accompanied by a hairstylist for public appearances.[380] In the 1990s, she was frequently photographed clutching distinctive handbags manufactured by Gucci and Dior, which became known as the Gucci Diana and Lady Dior.[399][400]

Following the opening of an exhibition of Diana's clothes and dresses at Kensington Palace in 2017, Catherine Bennett of The Guardian said such exhibitions are among the suitable ways to commemorate public figures whose fashion styles were noted due to their achievements. The exhibition suggests to detractors who, like many other princesses, "looking lovely in different clothes was pretty much her life's work" which also brings interest in her clothing.[401] Versace also pointed out that "[she doesn't] think that anyone, before or after her, has done for fashion what Diana did".[380] One of Diana's favourite milliners, John Boyd, said "Diana was our best ambassador for hats, and the entire millinery industry owes her a debt." Boyd's pink tricorn hat Diana wore for her honeymoon was later copied by milliners across the world and credited with rebooting an industry in decline for decades.[402][403]

Memorials

Permanent memorials to Diana include the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain in Hyde Park, London;[404] the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Playground in Kensington Gardens;[405] the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Walk, a circular path between Kensington Gardens, Green Park, Hyde Park, and St. James's Park;[406] the Diana Memorial Award, established in 1999 and later relaunched in 2007 by Gordon Brown;[407] the Statue of Diana, Princess of Wales, in the Sunken Garden of Kensington Palace;[408] and the Princess Diana Memorial in the garden of Schloss Cobenzl in Vienna, making it the first memorial dedicated to Diana in a German-speaking country.[409] The Flame of Liberty was erected in 1989 on the Place de l'Alma in Paris above the entrance to the tunnel in which the fatal crash later occurred. It became an unofficial memorial to Diana.[410][411] The Place de l'Alma was renamed Place Diana princesse de Galles in 2019.[412] Following her death, several countries issued postage stamps commemorating Diana, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Somalia, and Congo.[413][414][415] A bronze plaque was unveiled by Earl Spencer at Northampton Guildhall in 2002 as a memorial to his sister.[416]

There were two memorials inside Harrods department store, commissioned by Dodi Fayed's father, who owned the store from 1985 to 2010. The first memorial was a pyramid-shaped display containing photos of Diana and al-Fayed's son, a wine glass said to be from their last dinner, and a ring purchased by Dodi the day prior to the crash. The second, Innocent Victims, unveiled in 2005, was a bronze statue of Fayed dancing with Diana on a beach beneath the wings of an albatross.[417] In January 2018, it was announced that the statue would be returned to the al-Fayed family.[418] Diana's granddaughters, Charlotte Elizabeth Diana (born 2015)[419][420] and Lilibet Diana (born 2021),[421] as well as her niece, Charlotte Diana Spencer (born 2012),[422] are named after her.

In popular culture and art

Before and after her death, Diana has been the subject of films and television series and depicted in contemporary art. The first biopics about Diana and Charles were Charles & Diana: A Royal Love Story and The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana that were broadcast on American TV channels on 17 and 20 September 1981, respectively.[423] In December 1992, ABC aired Charles and Diana: Unhappily Ever After, a TV movie about marital discord between Diana and Charles.[424] Actresses who have portrayed Diana include Serena Scott Thomas (in Diana: Her True Story, 1993),[425] Julie Cox (in Princess in Love, 1996),[426] Amy Seccombe (in Diana: A Tribute to the People's Princess, 1998),[427] Michelle Duncan (in Whatever Love Means, 2005),[428] Genevieve O'Reilly (in Diana: Last Days of a Princess, 2007),[429][430] Nathalie Brocker (in The Murder of Princess Diana, 2007),[431] Naomi Watts (in Diana, 2013),[432] Jeanna de Waal (in Diana: The Musical, 2019–2021),[433] Emma Corrin (2020) and Elizabeth Debicki (in The Crown, 2022–2023),[434][435] and Kristen Stewart (in Spencer, 2021).[436]

In 2017, William and Harry commissioned two documentaries to mark the 20th anniversary of her death. The first of the two, Diana, Our Mother: Her Life and Legacy, was broadcast on ITV and HBO on 24 July 2017.[437][438] This film focuses on Diana's legacy and humanitarian efforts for causes such as AIDS, landmines, homelessness and cancer. The second documentary, Diana, 7 Days, aired on 27 August on BBC and focused on Diana's death and the subsequent outpouring of grief.[439]

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

Diana was born with the style of "The Honourable Diana Frances Spencer". When her father inherited the Earldom of Spencer in 1975, she became entitled to the style of "Lady Diana Spencer".[440] During her marriage, Diana was styled as "Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales". She additionally bore the titles Duchess of Rothesay,[441] Duchess of Cornwall,[441] Countess of Chester,[442][443] and Baroness of Renfrew.[441] After her divorce in 1996 and until her death, she was known as "Diana, Princess of Wales", without the style of "Her Royal Highness".[440] Though popularly referred to as "Princess Diana", that style is incorrect and one she never held officially.[b] She is still sometimes referred to in the media as "Lady Diana Spencer" or colloquially as "Lady Di". In a speech after her death, Tony Blair referred to Diana as "the people's princess".[445][446] Discussions were also held with the Spencer family and the British royal family as to whether Diana's HRH style needed to be restored posthumously, but Diana's family decided that it would be against her wishes and, thus, no formal offer was made.[447]

Honours

- Orders

- Foreign honours

- 1982: Supreme Class of the Order of the Virtues (or Order of al-Kamal) (Egypt)[177]

- 18 November 1982: Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown, bestowed by Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands[177]

- Appointments

- 1988: Royal Bencher of the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple[449]

- Fellowships

- 1988: The Royal College of Surgeons of England, Honorary Fellow in Dental Surgery[450]

- Freedom of the City

- 29 October 1981: Cardiff[451][452]

- 29 January 1986: Carlisle[453]

- 1987: London[225]

- 8 June 1989: Northampton Borough[416][454][455]

- 16 October 1992: Portsmouth[456]

Honorary military appointments

As Princess of Wales, Diana held the following military appointments:

- Australia

- Colonel-in-Chief of the Royal Australian Survey Corps[457]

- Canada

- Colonel-in-Chief of the Princess of Wales' Own Regiment[189] (17 August 1985 to 16 July 1996)[458]

- Colonel-in-Chief of the West Nova Scotia Regiment

- United Kingdom

- Colonel-in-Chief of the Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment[302]

- Colonel-in-Chief of the Light Dragoons[302]

- Colonel-in-Chief of the Royal Hampshire Regiment[189]

- Colonel-in-Chief of the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own)[189]

- Honorary Air Commodore, RAF Wittering[459]

- Lady Sponsor of HMS Cornwall (F99)[460]

- Lady Sponsor of HMS Vanguard (S28)[461][462]

She relinquished these appointments following her divorce.[26][128]

Other appointments

- 15 November 1984: Lady Sponsor of Royal Princess[463]

Arms

|

|

Descendants

| Name | Birth | Marriage | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | |||

| William, Prince of Wales | 21 June 1982 | 29 April 2011 | Catherine Middleton | Prince George of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales Prince Louis of Wales |