The King of the Golden Mountain

| The King of the Golden Mountain | |

|---|---|

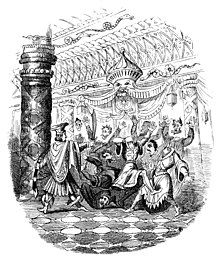

1876 illustration by George Cruikshank | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The King of the Golden Mountain |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 810 + AaTh 401A, "The Enchanted Princess in Her Castle" + ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife" |

| Country | Germany |

| Published in | Grimm's Fairy Tales |

"The King of the Golden Mountain" (German: Der König vom goldenen Berg) is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in Grimm's Fairy Tales (KHM 92).[1][2][3]

The main version anthologized was taken down from a soldier; there is also a variant collected from Zwehrn (Zweheren) whose storyline summarized by Grimm in his notes.[4]

Synopsis

[edit]

A merchant with a young son and daughter lost everything except a field. Walking in that field, he met a black mannikin (dwarf)[a] who promised to make him rich if, in twelve years, he brought the first thing that rubbed against his leg when he went home. The merchant agreed. When he got home, his boy rubbed against his leg. He went to the attic and found money, but when the twelve years were up, he grew sad. His son got the story from him and assured him that the black man had no power over him. The son had himself blessed by the priest and went to argue with the black man. Finally, the mannikin agreed that the boy could be put in a boat and shoved off into the water.

The boat carried him to another shore. A snake met him, but was a transformed princess. She told him if for three nights he let twelve black men beat him, she would be freed. He agreed and did it, and she married him, making him the King of the Golden Mountain, and in time bore him a son. When the boy was seven, the king wanted to see his own parents. His wife thought it would bring evil, but gave him a ring that would wish him to his parents and back again, telling him must not wish her to come with him. He went, but to get in the town, he had to put off his fine and magnificent clothing for a shepherd's; once inside, first he had to persuade his parents that he was their son, and then he could not persuade him that he was a king. Frustrated, he wished his wife and son with him. When he slept, his wife took the ring and wished herself and their son back to the Golden Mountain.

He walked until he found three giants quarreling over their inheritance: a sword that would cut off all heads but the owner's, if ordered to; a cloak of invisibility; and boots that would carry the wearer anywhere. He said he had to try them first, and with them, went back to the Golden Mountain, where his wife was about to marry another man. But at the banquet she was unable to enjoy any of the food or wine because the hero would invisibly take them away and consume them. The dismayed queen ran to her chamber, whereupon the hero revealed himself to her, rebuking her betrayal. Now addressing himself to the guests in the hall, he declared the wedding called off, as he was the rightful ruler, asking the guests to leave. As they refused to do this, and tried to seize him, the hero invoked the command to his magic sword, and all other heads rolled off. He had now again assumed his place as King of the Golden Mountain.

Analysis

[edit]Tale type

[edit]American folklorist D. L. Ashliman classified the story as types AaTh 401A ("The Enchanted Princess in Her Castle"), with an introduction of type 810 ("The Devil Loses a Soul That Was Promised Him"), and other episodes of type 560 ("The Magic Ring") and of type 518, ("Quarreling Giants Lose Their Magic Objects").[1][5]

The tale is classified in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as type ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife":[6][7] the hero finds a maiden of supernatural origin (e.g., the swan maiden) or rescues a princess from an enchantment; either way, he marries her, but she disappears to another place. He goes after her on a long quest, often helped by the elements (Sun, Moon and Wind) or by the rulers of animals of the land, sea and air (often in the shape of old men and old women).[8][9][10]

The middle episode of the hero acquiring magic objects that help in his journey is classified as tale type ATU 518, "Men Fight Over Magic Objects": hero tricks or buys magic items from quarreling men (or giants, trolls, etc.).[11][12][13] Despite its own catalogation, folklorists Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther argue that this narrative does not exist as an independent tale type, and usually appears in combination with other tale types, especially ATU 400.[14][15]

The sequence of the hero enduring three nights of suffering in the princess's castle in order to rescue her is classified as tale type AaTh 401A, "The Enchanted Princess and their Castles".[16] However, German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther, in his revision of the international index, published in 2004, subsumed tale type AaTh 401A under the more general tale type ATU 400, "The Man on a Quest for the Lost Wife".[17] Even Stith Thompson noted the great similarity between both types, but remarked that, in type 401, the story is more focused on the princess's disenchantment.[18]

See also

[edit]- The Girl Without Hands

- The Beautiful Palace East of the Sun and North of the Earth

- The Blue Mountains

- The Three Princesses of Whiteland

- Maid Lena (Danish fairy tale)

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ German Männchen, rendered "dwarf" in Edgar Taylor's translation,[2] and "mannikin" in Margaret Hunt's.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ashliman, D. L. (2020). "Grimm Brothers' Children's and Household Tales (Grimms' Fairy Tales)". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ a b Taylor tr. (1823).

- ^ a b Hunt tr. (1884).

- ^ Hunt tr. (1884), pp. 391–393.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2021). Handbuch zu den "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" der Brüder Grimm: Entstehung – Wirkung – Interpretation (in German). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 204–206. doi:10.1515/9783110747584-001.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1968). One hundred favorite folktales. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 436 (classification for tale nr. 20).

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne-Thompson Classification System. Bibliographies and Indexes in World Literature, vol. 11. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1987. pp. 79-80. ISBN 0-313-25961-5.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1973 [1961]. pp. 128–129.

- ^ Pen, Jikke. "De man zoekt zijn verdwenen vrouw". In: Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties. 1ste druk. Ton Dekker & Jurjen van der Kooi & Theo Meder. Kritak: Sun. 1997. pp. 226-227.

- ^ Liungman, Waldemar (2022) [1961]. Die Schwedischen Volksmärchen: Herkunft und Geschichte. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. p. 81. doi:10.1515/9783112618004-004.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. pp. 75-76. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Third printing. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1973 [1961]. p. 186.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 306. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 306. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Rühle, Stefanie (2016) [2002]. "Prinzessin als Hirschkuh (AaTh 401)" [The Girl Transformed into an Animal]. In Rolf Wilhelm Brednich; Heidrun Alzheimer; Hermann Bausinger; Wolfgang Brückner; Daniel Drascek; Helge Gerndt; Ines Köhler-Zülch; Klaus Roth; Hans-Jörg Uther (eds.). Enzyklopädie des Märchens Online (in German). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. p. 1352. doi:10.1515/emo.10.251.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 231. ISBN 978-951-41-0963-8.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

One such tale is little more than a variation of the story about The Man on a Quest for His Lost Wife (Type 400), and is frequently referred to as being a sub-type of that tale.

- Bibliography

- Grimm (1884). The King of the Golden Mountain. Vol. 2. Margaret Hunt, tr. London: George Bell and sons. pp. 28–34, 391–393.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Grimm (1823). The King of the Golden Mountain. Taylor, Edgar, tr.; Cruikshank, George, illustr. London: C. Baldwyn. pp. 169–178, 234–235.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

[edit] Works related to The King of the Golden Mountain at Wikisource

Works related to The King of the Golden Mountain at Wikisource Media related to The King of the Golden Mountain at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The King of the Golden Mountain at Wikimedia Commons- The complete set of Grimms' Fairy Tales, including The King of the Golden Mountain at Standard Ebooks