Fountain of Youth

The Fountain of Youth is a mythical spring which supposedly restores the youth of anyone who drinks or bathes in its waters. Tales of such a fountain have been recounted around the world for thousands of years, appearing in the writings of Herodotus (5th century BC), in the Alexander Romance (3rd century AD), and in the stories of Prester John (early Crusades, 11th/12th centuries AD). Stories of similar waters also featured prominently among the people of the Caribbean during the Age of Exploration (early 16th century); they spoke of the restorative powers of the water in the mythical land of Bimini. Based on these many legends, explorers and adventurers looked for the elusive Fountain of Youth or some other remedy to aging, generally associated with magic waters. These waters might have been a river, a spring or any other water-source said to reverse the aging process and to cure sickness when swallowed or bathed in.

The legend became particularly prominent in the 16th century, when it became associated with the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León, the first Governor of Puerto Rico. Ponce de León was supposedly searching for the Fountain of Youth when he traveled to Florida in 1513. Legend has it that Native Americans told Ponce de León that the Fountain of Youth was in Bimini.

Early accounts

[edit]Herodotus mentions a fountain containing a special kind of water in the land of the Macrobians, which gives the Macrobians their exceptional longevity.

The Ichthyophagid then in their turn questioned the king concerning the term of life, and diet of his people, and were told that most of them lived to be a hundred and twenty years old, while some even went beyond that age—they ate boiled flesh, and had for their drink nothing but milk. When the Ichthyophagi showed wonder at the number of the years, he led them to a fountain, wherein when they had washed, they found their flesh all glossy and sleek, as if they had bathed in oil- and a scent came from the spring like that of violets. The water was so weak, they said, that nothing would float in it, neither wood, nor any lighter substance, but all went to the bottom. If the account of this fountain be true, it would be their constant use of the water from it which makes them so long-lived.[1]

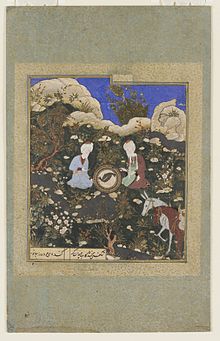

A story of the "Water of Life" appears in the Eastern versions of the Alexander romance, which describes Alexander the Great and his servant crossing the Land of Darkness to find the restorative spring. The servant in that story is in turn derived from Middle Eastern legends of Al-Khidr, a sage who appears also in the Qur'an. Arabic and Aljamiado versions of the Alexander Romance were very popular in Spain during and after the period of Moorish rule, and would have been known to the explorers who journeyed to America. These earlier accounts inspired the popular medieval fantasy The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, which also mentions the Fountain of Youth as located at the foot of a mountain outside Polombe (modern Kollam[2]) in India.[3] Due to the influence of these tales, the Fountain of Youth legend was popular in courtly Gothic art, appearing for example on the ivory Casket with Scenes of Romances (Walters 71264) and several ivory mirror-cases, and remained popular through the European Age of Exploration.[4]

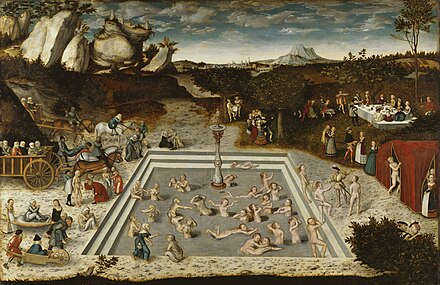

European iconography is fairly consistent, as the Cranach painting and mirror-case Fons Juventutis (The Fountain of Youth) from 200 years earlier demonstrate: old people, often carried, enter at left, strip, and enter a pool that is as large as space allows. The people in the pool are youthful and naked, and after a while they leave it, and are shown fashionably dressed enjoying a courtly party, sometimes including a meal.

There are countless indirect sources for the tale as well. Eternal youth is a gift frequently sought in myth and legend, and stories of things such as the philosopher's stone, universal panaceas, and the elixir of life are common throughout Eurasia and elsewhere.[5]

An additional inspiration may have been taken from the account of the Pool of Bethesda where a paralytic man was healed in the Gospel of John. In the possibly interpolated John 5:2–4, the pool is said to be periodically stirred by an angel, upon which the first person to step into the water would be healed of whatever afflicted them.

Bimini

[edit]According to legend, the Spanish heard of Bimini from the Arawaks in Hispaniola, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The Caribbean islanders described a mythical land of Beimeni or Beniny (whence Bimini), a land of wealth and prosperity, which became conflated with the fountain legend. By the time of Ponce de Leon, the land was thought to be located northwest towards the Bahamas (called la Vieja during the Ponce expedition). The natives were probably referring to the area occupied by the Maya.[4] This land also became confused with the Boinca or Boyuca mentioned by Juan de Solis, although Solis's navigational data placed it in the Gulf of Honduras. It was this Boinca that originally held a legendary fountain of youth, rather than Bimini itself.[4] Sequene, an Arawak chief from Cuba, purportedly was unable to resist the lure of Bimini and its restorative fountain. He gathered a troupe of adventurers and sailed north, never to return.

Found within the salt water mangrove swamp that covers 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) of the shoreline of North Bimini is The Healing Hole, a pool that lies at the end of a network of winding tunnels. During outgoing tides, these channels pump cool, mineral-laden fresh water into the pool. Because this well was carved out of the limestone rock by ground water thousands of years ago it is especially high in calcium and magnesium.[citation needed] Magnesium, which has been shown to improve longevity and reproductive health,[6][7] is present in large quantities in the sea water.[8] While it is not known whether any legend about healing waters was widespread among the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, the Italian-born chronicler Peter Martyr attached such a story drawn from ancient and medieval European sources to his account of the 1514 voyage of Juan Diaz de Solis in a letter to the Pope in 1516, though he did not believe the stories and was dismayed that so many others did.[9][10]

Ponce de León

[edit]

In the 16th century the story of the Fountain of Youth became attached to the biography of the conquistador Juan Ponce de León. As attested by his royal charter, Ponce de León was charged with discovering the land of Beniny.[4] Although the indigenous peoples were probably describing the land of the Maya in Yucatán, the name—and legends about Boinca's fountain of youth—became associated with the Bahamas instead. However, Ponce de León did not mention the fountain in any of his writings throughout the course of his expedition.[4]

The connection was made in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés's Historia general y natural de las Indias of 1535,[11] in which he wrote that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to regain youthfulness.[12] Some researchers have suggested that Oviedo's account may have been politically inspired to generate favor in the courts.[4] A similar account appears in Francisco López de Gómara's Historia general de las Indias of 1551.[13] In the Memoir of Hernando d'Escalante Fontaneda in 1575, the author places the restorative waters in Florida and mentions de León looking for them there; his account influenced Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas' unreliable history of the Spanish in the New World.[14] Fontaneda had spent seventeen years as an Indian captive after being shipwrecked in Florida as a boy. In his Memoir he tells of the curative waters of a lost river he calls "Jordan" and refers to de León looking for it. However, Fontaneda makes it clear he is skeptical about these stories he includes, and says he doubts de León was actually looking for the fabled stream when he came to Florida.[14]

Herrera makes that connection definite in the romanticized version of Fontaneda's story included in his Historia general de los hechos de los Castellanos en las islas y tierra firme del Mar Oceano. Herrera states that local caciques paid regular visits to the fountain. A frail old man could become so completely restored that he could resume "all manly exercises … take a new wife and beget more children." Herrera adds that the Spaniards had unsuccessfully searched every "river, brook, lagoon or pool" along the Florida coast for the legendary fountain.[15]

Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park

[edit]

The city of St. Augustine, Florida, is home to the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, a tribute to the spot where Ponce de León was supposed to have landed according to promotional literature, although there is no historical or archaeological evidence to support the claim. There were several instances of the property being used as an attraction as early as the 1860s; the tourist attraction in its present form was created by Luella Day McConnell in 1904. Having abandoned her practice as a physician in Chicago and gone to the Yukon during the Klondike gold rush of the 1890s, she purchased the Park property in 1904 from Henry H. Williams, a British horticulturalist, with cash and diamonds, for which she became known in St. Augustine as "Diamond Lil".

Around the year 1909 she began advertising the attraction, charging admission, and selling post cards and water from a well dug in 1875 for Williams by Philip Gomez and Philip Capo.[16][17] McConnell later claimed to have "discovered" on the grounds a large cross made of coquina rock, asserting it was placed there by Ponce de León himself.[18] She continued to fabricate stories to amuse and appall the city's residents and tourists until her death in a car accident in 1927.

Walter B. Fraser, a transplant from Georgia who managed McConnell's attraction, then bought the property and made it one of the state's most successful tourist attractions.[19] The first archaeological digs at the Fountain of Youth were performed in 1934 by the Smithsonian Institution. These digs revealed a large number of Christianized Timucua burials. These burials eventually pointed to the Park as the location of the first Christian mission in the United States. Called the Mission Nombre de Dios, this mission was begun by Franciscan friars in 1587. Succeeding decades have seen the unearthing of items which positively identify the Park as the location of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés's 1565 settlement of St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in North America. The park currently exhibits native and colonial artifacts to celebrate Ponce de León and Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the founder of St. Augustine. Exhibits of Timucua and Spanish heritage are also on display.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Herodotus, Book III: 23

- ^ Kohanski, Tamarah & Benson, C. David (Eds.) The Book of John Mandeville. Medieval Institute Publications (Kalamazoo), 2007. "Indexed Glossary of Proper Names". Accessed 24 Sept 2011.

- ^ Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Accessed 24 Sept 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Peck, Douglas T. "Misconceptions and Myths Related to the Fountain of Youth and Juan Ponce de Leon's 1513 Exploration Voyage" (PDF). New World Explorers, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ^ Zorea, Aharon (2017). Finding the Fountain of Youth: The Science and Controversy Behind Extending Life and Cheating Death. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 35–39. ISBN 978-1-4408-3798-2.

- ^ Epidemiology OF Water Magnesium; Evidence of Contributions to Health Mildred S. Seelig, M.D., M.P.H., Master of American College of Nutrition; Adjunct Professor of Nutrition, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (in Press: Proceedings of Mg Symposium, Vichy, France 2000)

- ^ Motta R, Louis JP, Frank G, Henrotte JG (1998). "Unexpected association between reproductive longevity and blood magnesium levels in a new model of selected mouse strains". Growth, Development, and Aging. 62 (1–2): 37–45. PMID 9666355.

- ^ "Dissolved mineral sources and significance". Archived from the original on 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- ^ Pedro Mártir de Angleria. Decadas de Nuevo Mundo, Decada 2, chapter X.

- ^ Douglas T. Peck, "Anatomy of a Historical Fantasy," Revista de Historia de América ): p. 69y

- ^ Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo (1851) [1535]. José Amador de los Ríos (ed.). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Madrid: La Real Academia de la Historia. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo (1851) [1535]. "XVI". In José Amador de los Ríos (ed.). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Madrid: La Real Academia de la Historia. pp. 482–485. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Francisco López de Gómara. Historia general de las Indias, second part.

- ^ a b "Fontaneda's Memoir". Translation by Buckingham Smith, 1854. From keyshistory.org. Retrieved July 14, 2006.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages 1492–1616 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), p. 504.

- ^ Sujin Kim; Robert 0. Jones (April 29, 2016). "National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Summary" (PDF). nps.gov. National Park Service. p. 3. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Harold Ballou; Roger W. Toll. "Proposed Fountain of Youth Monument to the 72nd Congress" (PDF). pp. 6–7.

Presumably, Ponce de Leon's first landing was north of St. Augustine and south of Jacksonville. The exact spot of the landing will probably never be known. The claim that the actual site of the landing has been definitely established at the Fountain of Youth Park seems unsupported by satisfactory evidence. The Fountain of Youth seems to be a well, not a spring, and to be without authenticated historical importance. One gets the impression that an effort is made to give the tourists their money's worth and to popularize history with such revisions as will best serve the gate receipts, and that in so doing historical accuracy has suffered.

- ^ Reynolds, Charles Bingham (1934). The Landing of Ponce de Leon: A Historical Review (PDF). pp. 6–7.

ln 1909 when a tree near the well was uprooted by a storm. Mrs. McConnell gave out the fantastic story that she had discovered in the hole left by the upturned roots what proved to be a cross formed of chunks of coquina, disposed 15 in the upright and 13 in the cross-beam, having been placed thus by Ponce de Leon to commemorate the year 1513 of his discovery...She also identified the site of a mission chapel built by Ponce de Leon and some of the coquina building blocks still remaining to mark the site. It is pertinent to recall that wherever Ponce made his first landing he remained at the place only five days. This story told by Mrs. McConnell of the Ponce de Leon coquina cross and its discovery by her was the origin of the myth that Ponce de Leon landed at Hospital Creek. Her ingenious invention found immediate acceptance and endorsement in a quarter one might least suspect.

- ^ James C. Clark (23 September 2014). A Concise History of Florida. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-62585-153-6.