Farmers' Almanac

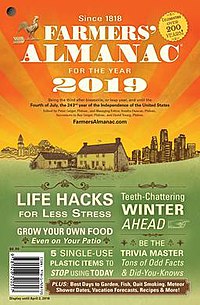

Cover of the 2019 Farmers' Almanac | |

| Editor Managing Editor | Peter Geiger Sandi Duncan |

|---|---|

| Former editors | Ray Geiger William Jardine Berlin Hart Wright Samuel Hart Wright David Young |

| Categories | Almanacs |

| Frequency | Annually |

| Publisher | Almanac Publishing Company |

| First issue | 1818 |

| Company | Geiger |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Website | farmersalmanac |

| ISSN | 0737-6731 |

Farmers' Almanac is an annual American periodical that has been in continuous publication since 1818. Published by Geiger of Lewiston, Maine, the Farmers' Almanac provides long-range weather predictions for both the U.S. and Canada. The periodical also provides calendars and articles on topics such as full moon dates, folklore, natural remedies, and the best days to do various outdoor activities.

Each new year's edition is released at the end of August of the previous year and contains 16 months of weather predictions broken into 7 zones for the continental U.S., as well as seasonal weather maps for the winter and summer ahead.

In addition to the U.S. version, there is a Canadian Farmers' Almanac, an abbreviated "Special Edition" sold at Dollar General stores,[1] and a Promotional Version that is sold to businesses as a marketing and public relations tool.

The publication follows in the heritage of American almanacs such as Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard's Almanack.[2][3][4]

History

[edit]Founded in 1818, the Farmers’ Almanac mixes a blend of long-range weather predictions, humor, fun facts, and advice on gardening, cooking, fishing, conservation, and other topics.

The Farmers’ Almanac has had seven editors. Poet, astronomer, and teacher David Young held the post for 34 years starting from when he and publisher Jacob Mann first founded The Almanac Publishing Company in Morristown, New Jersey. Following Young's death in 1852, astronomer Samuel Hart Wright became editor.

In 1933, Ray Geiger took over as the sixth editor of the Farmers’ Almanac and began what became the longest-running editorship in Farmers’ Almanac history.

In 1994, Ray's son Peter became editor. Sandi Duncan is now Managing Editor with him. Sandi was the first female editor in 178 years to hold an editorial position.

In 1997, an online version was created at FarmersAlmanac.com. The Almanac has over 1.2 million followers on Facebook, and is also on Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, TikTok[5] and other social media sites.[6]

Weather prediction

[edit]

Predictions for each edition are made as far as two years in advance. The U.S. retail edition of the Farmers' Almanac contains weather predictions for 7 U.S. climatic zones, defined by the publishers, in the continental United States, broken into 3-day intervals. Seasonal maps and summaries for each season are also shared in each new edition, as are forecasts for annual sporting events. Predictions cover 16 months, from the previous September (through December of the publication year).

The Farmers' Almanac will only state publicly that their method is an "exclusive mathematical and astronomical formula, that relies on sunspot activity, tidal action, planetary position (astrology) and many other factors". The Almanac's forecaster is referred to by the pseudonym Caleb Weatherbee. According to the publishers, the true identity of the forecaster is kept secret to prevent them from being "badgered".

Accuracy

[edit]Publishers claim that "many longtime Almanac followers claim that their forecasts are 80% to 85% accurate" on their website. Their website also contains a list of the many more "famous" weather predictions they have accurately forewarned of and like to point out that they have been predicting the weather longer than the National Weather Service.

Most scientific analyses of the accuracy of Farmers' Almanac forecasts have shown a 50% rate of accuracy,[7][8] which is higher than that of groundhog prognostication, a folklore method of forecasting.[9] USA Today states that "according to numerous media analyses neither the Old Farmer's Almanac nor the Farmers' Almanac gets it right".[10]

Notable articles

[edit]Most editions of the Farmers' Almanac include a "human crusade," advocating for a change in some accepted social practice or custom. Previous crusades have included: "How Much Daylight Are We Really Saving," a recommendation for a revised Daylight Saving Time schedule (2007); "Why is Good Service So Hard to Schedule," recommending that service providers offer more specific timeframes when scheduling home visits (2006); "A Kinder, Gentler Nation," urging readers to exercise more common courtesy (2003); "Saturday: The Trick to Making Halloween a Real Treat," advocating that the observance of Halloween be moved to the last Saturday in October (1999); "A Cure for Doctors' Office Delays," demanding more prompt medical service and calling for a "Patients' Bill of Rights" (1996); and "Pennies Make No Sense," which sought to eliminate the penny, and to permanently replace the dollar bill with less costly-to-produce dollar coins (1989).[11]

Other pieces that have attracted attention over the years include:

- Farmers' Almanac's 2010 list of the "5 Worst Weather Cities",[12] which elicited a call for retraction from syracuse.com[13] after naming Syracuse, New York, the worst winter weather city.

- The 2014 Winter Outlook,[14] which called for a winter storm to hit just about the time Super Bowl XLVIII was to be played at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey (no such storm materialized, and the weather was actually warmer than average at the time of the event).[15] However, a major winter storm did strike the area the day after the game.

- The 2001 campaign to name an official National Dessert (readers resoundingly responded in favor of traditional apple pie).[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Where to Buy - U.S." Farmers' Almanac.

- ^ Park, Edwards (November 1992). "Weathering Every Season with One Canhjny Compendium". Smithsonian Magazine: 91.

- ^ Mettee, Stephen Blake; Doland, Michelle; Hall, Doris (December 2005). The American Directory of Writer's Guidelines. Quill Driver Books. ISBN 9781884956515. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ Bates, Christopher (April 8, 2015). The Early Republic and Antebellum America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History. NY, NY: Routledge. p. 830. ISBN 978-1-3174-5740-4. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ^ "Farmers' Almanac (@farmersalmanac) Official TikTok | Watch Farmers' Almanac's Newest TikTok Videos". TikTok. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ Staff, Farmers' Almanac. "Advertise With Us". Farmers' Almanac. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ O'Lenic, Ed (February 2, 1996). "ED O'LENIC, NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE". PBS NewsHour.

- ^ Walsh, John E.; David Allen (October 1981). "Testing the Farmer's Almanac". Weatherwise. 34 (5): 212–215. doi:10.1080/00431672.1981.9931980.

- ^ "How Accurate Are Punxsutawney Phil's Groundhog Day Forecasts?". Live Science. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Think almanacs can predict 2015 weather? Think again".

- ^ "Pennies Make No Sense But A 12½-Cent Coin Makes A Bit". farmersalmanac.com/. Almanac Publishing Company. 1989. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ Weatherbee, Caleb. "5 Worst Winter Weather Cities". Farmers' Almanac. Almanac Publishing Company. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Hey Farmers' Almanac, we demand a retraction. Syracuse is a Winter wonderland". syracuse.com. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Weatherbee, Caleb. "The "Days of Shivery" are Back! Read Our 2014 Forecast!". Farmers' Almanac. Almanac Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Belson, Ken (23 November 2013). "Almanacs Foresee a Super Bowl to Test Fans' Resolve, and Snow Gear". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2013.