Coventry Carol

| Coventry Carol | |

|---|---|

Massacre of the Innocents, by Cornelis van Haarlem, 1591 | |

| Genre | Christmas music |

| Text | Robert Croo (oldest known) |

| Language | English |

The "Coventry Carol" is an English Christmas carol dating from the 16th century. The carol was traditionally performed in Coventry in England as part of a mystery play called The Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors. The play depicts the Christmas story from chapter two in the Gospel of Matthew: the carol itself refers to the Massacre of the Innocents, in which Herod ordered all male infants under the age of two in Bethlehem to be killed, and takes the form of a lullaby sung by mothers of the doomed children.

The music contains a well-known example of a Picardy third. The author is unknown; the oldest known text was written down by Robert Croo in 1534, and the oldest known setting of the melody dates from 1591.[1] There are alternative, modern settings of the carol by Kenneth Leighton, Philip Stopford and Michael McGlynn.

History and text

[edit]The carol is the second of three songs included in the Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors, a nativity play that was one of the Coventry Mystery Plays, originally performed by the city's guilds.

The exact date of the text is unknown, though there are references to the Coventry guild pageants from 1392 onwards. The single surviving text of the carol and the pageant containing it was edited by one Robert Croo, who dated his manuscript 14 March 1534.[2] Croo, or Crowe, acted for some years as the 'manager' of the city pageants. Over a twenty-year period, payments are recorded to him for playing the part of God in the Drapers' Pageant,[3] for making a hat for a "pharysye", and for mending and making other costumes and props, as well as for supplying new dialogue and for copying out the Shearmen and Tailors' Pageant in a version which Croo described as "newly correcte".[4] Croo seems to have worked by adapting and editing older material, while adding his own rather ponderous and undistinguished verse.[4]

Religious changes caused the plays' suppression during the later 16th century, but Croo's prompt book, including the songs, survived and a transcription was eventually published by the Coventry antiquarian Thomas Sharp in 1817 as part of his detailed study of the city's mystery plays.[2] Sharp published a second edition in 1825 which included the songs' music. Both printings were intended to be a facsimile of Croo's manuscript, copying both the orthography and layout; this proved fortunate as Croo's original manuscript, which had passed into the collection of the Birmingham Free Library, was destroyed in a fire there in 1879.[2] Sharp's transcriptions are therefore the only source; Sharp had a reputation as a careful scholar, and his copying of the text of the women's carol appears to be accurate.[5]

Within the pageant, the carol is sung by three women of Bethlehem, who enter on stage with their children immediately after Joseph is warned by an angel to take his family to Egypt:[6]

| Original spelling[7] | Modernised spelling[8] |

|---|---|

Lully, lulla, thow littell tine child, |

Lully, lullah, thou little tiny child, |

O sisters too, how may we do |

O sisters too, how may we do |

Herod, the king, in his raging, |

Herod the king, in his raging, |

That wo is me, pore child, for thee, |

That woe is me, poor child, for thee |

Sharp's publication of the text stimulated some renewed interest in the pageant and songs, particularly in Coventry itself. Although the Coventry mystery play cycle was traditionally performed in summer, the lullaby has been in modern times regarded as a Christmas carol. It was brought to a wider audience after being featured in the BBC's Empire Broadcast at Christmas 1940, shortly after the Bombing of Coventry in World War II, when the broadcast concluded with the singing of the carol in the bombed-out ruins of the Cathedral.[9]

Music

[edit]The carol's music was added to Croo's manuscript at a later date by Thomas Mawdyke, his additions being dated 13 May 1591. Mawdyke wrote out the music in three-part harmony, though whether he was responsible for its composition is debatable, and the music's style could be indicative of an earlier date.[10] The three (alto, tenor and baritone) vocal parts confirm that, as was usual with mystery plays, the parts of the "mothers" singing the carol were invariably played by men.[10] The original three-part version contains a "startling" false relation (F♯ in treble, F in tenor) at "by, by".[11]

Mawdyke, who may be identifiable with a tailor of that name living in the St Michael's parish of Coventry in the late 16th century, is thought to have made his additions as part of an unsuccessful attempt to revive the play cycle in the summer of 1591, though in the end the city authorities chose not to support the revival.[12] The surviving pageants were revived in the Cathedral from 1951 onwards.

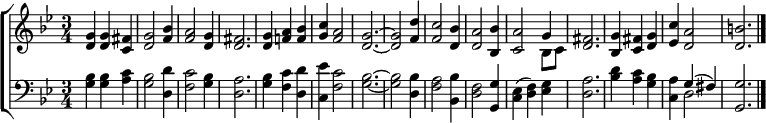

A four-part setting of the tune by Walford Davies is shown below:[13]

"Appalachian" variant

[edit]A variant of the carol was supposedly collected by folklorist John Jacob Niles in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, in June 1934 (from an "old lady with a gray hat", who according to Niles's notes insisted on remaining anonymous).[14] Niles surmised that the carol had been transplanted from England via the shape note singing tradition, although this version of the carol has not been found elsewhere and there is reason to believe that Niles, a prolific composer, actually wrote it himself.[15] Joel Cohen uncovered an early shape note choral song from the 18th century which also includes some of the lyrics to the Coventry Carol and has a tune at least marginally resembling Niles' variant. For this reason, Cohen argued that the Appalachian variant was likely to be authentic and that Crump et al. have been too quick to assume chicanery on Niles' part due to his proclivity for editing some of his collected material.

Although the tune is quite different to that of the "Coventry Carol", the text is largely similar except for the addition of an extra verse (described by Poston as "regrettable"):

And when the stars ingather do

In their far venture stay

Then smile as dreaming, little one,

By, by, lully, lullay.[16]

A number of subsequent recorded versions have incorporated the fifth verse.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Studwell, W. E. (1995). The Christmas Carol Reader. Haworth Press. pp. 15 ISBN 978-1-56023-872-0

- ^ a b c Rastall, Richard (2001). Minstrels Playing: Music in Early English Religious Drama. Boydell and Brewer. p. 179.

- ^ King and Davidson, The Coventry Corpus Christi plays, Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2000, p. 53

- ^ a b King, Pamela M. (1990). "Faith, Reason and the Prophets' dialogue in the Coventry Pageant of the Shearmen and Taylors". In Redmond, James (ed.). Drama and Philosophy. Themes in Drama. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–46. ISBN 978-0-521-38381-3.

- ^ Cutts, John P. (Spring 1957). "The Second Coventry Carol and a Note on The Maydes Metamorphosis". Renaissance News. 10 (1): 3–8. doi:10.2307/2857697. JSTOR 2857697.

- ^ Glover (ed.) The Hymnal 1982 Companion, Volume 1, 1990, p. 488

- ^ Manly, John Matthews (1897). Specimens of the Pre-Shakesperean Drama. Vol. I. The Athenæum Press. pp. 151–152. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Lawson-Jones, Mark (2011). "The Coventry Carol". Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree?: The History of Christmas Carols. The History Press. pp. 44–49. ISBN 978-0-7524-7750-3.

- ^ Wiebe, Heather. Britten's Unquiet Pasts: Sound and Memory in Postwar Reconstruction, Cambridge University Press, p. 192

- ^ a b Duffin, A Performer's Guide to Medieval Music, Indiana University Press, 259

- ^ Gramophone, volume 66, issues 21988–21989, p. 968

- ^ Rastall 2001, p. 180.

- ^ Coventry Carol at the Choral Public Domain Library. Accessed 2016-09-07.

- ^ See notes to I Wonder as I Wander – Love Songs and Carols, John Jacob-Niles, Tradition TLP 1023 (1957).

- ^ Crump (ed). The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3rd ed., McFarland, 2001, p. 154

- ^ Poston, E. The Second Penguin Book of Christmas Carols, Penguin, 1970

External links

[edit]- Sheet music for voice and SATB from Cantorion.org

- Amman, Douglas D. (1986). The slaying of the innocents: a relational treatise on composition and conducting (Thesis). Ball State University.