Britpop

| Britpop | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Early 1990s, United Kingdom |

| Derivative forms | Post-Britpop |

| Subgenres | |

| New wave of new wave | |

| Other topics | |

Britpop was a mid-1990s British-based music culture movement that emphasised Britishness. Musically, Britpop produced bright, catchy alternative rock, in reaction to the darker lyrical themes and soundscapes of the US-led grunge music and the UK's own shoegaze music scene. The movement brought British alternative rock into the mainstream and formed the larger British popular cultural movement, Cool Britannia, which evoked the Swinging Sixties and the British guitar pop of that decade.

Britpop was a phenomenon that highlighted bands emerging from the independent music scene of the early 1990s. Although often seen as a cultural moment rather than a distinct musical genre, its associated bands typically drew inspiration from the British pop music of the 1960s, the glam rock and punk rock of the 1970s, and the indie pop of the 1980s.

The most successful bands linked with Britpop were Oasis, Blur, Suede and Pulp, known as the "big four" of the movement. The timespan of Britpop is generally considered to be 1993–1997, and its peak years to be 1995–1996. A chart battle between Blur and Oasis (dubbed "The Battle of Britpop") brought the movement to the forefront of the British press in 1995. While music was the main focus, fashion, art and politics also got involved, with Tony Blair and New Labour aligning themselves with the movement.

During the late 1990s, many Britpop acts began to falter commercially or break up, or otherwise moved towards new genres or styles. Commercially, Britpop lost out to teen pop, while artistically it segued into a post-Britpop indie movement, associated with bands such as Travis and Coldplay.

Style, roots and influences

[edit]Though Britpop has sometimes been viewed as a marketing tool and more of a cultural moment than a distinct musical genre,[1][2][3] there are musical conventions and influences the bands grouped under the Britpop term have in common. Britpop bands show elements from the British pop music of the 1960s, glam rock and punk rock of the 1970s, and indie pop of the 1980s in their music, attitude, and clothing. Specific influences vary: Blur drew from the Kinks and early Pink Floyd, Oasis took inspiration from the Beatles, and Elastica had a fondness for arty punk rock, notably Wire [citation needed] and both incarnations of Adam and the Ants.[4] Regardless, Britpop artists project a sense of reverence for British pop sounds of the past.[5] The Kinks' Ray Davies and XTC's Andy Partridge are sometimes advanced as the "godfathers" or "grandfathers" of Britpop,[6] though Davies disputes it.[7] Others similarly labelled include Paul Weller[8] and Adam Ant.[9]

Alternative rock acts from the indie scene of the 1980s and early 1990s were the direct ancestors of the Britpop movement. The influence of the Smiths is common to the majority of Britpop artists.[10] The Madchester scene, fronted by the Stone Roses, Happy Mondays and Inspiral Carpets (for whom Oasis's Noel Gallagher had worked as a roadie during the Madchester years), was an immediate root of Britpop since its emphasis on good times and catchy songs provided an alternative to the British-based shoegazing and American based grunge styles of music.[11] Pre-dating Britpop by four years, Liverpool-based group the La's hit single "There She Goes" was described by Rolling Stone as a "founding piece of Britpop's foundation".[12]

Local identity and regional British accents are common to Britpop groups, as well as references to British places and culture in lyrics and image.[1] Stylistically, Britpop bands use catchy hooks and lyrics that were relevant to young British people of their own generation.[11] Britpop bands conversely denounced grunge as irrelevant and having nothing to say about their lives. In contrast to the dourness of grunge, Britpop was defined by "youthful exuberance and desire for recognition".[13] Damon Albarn of Blur summed up the attitude in 1993 when after being asked if Blur were an "anti-grunge band" he said, "Well, that's good. If punk was about getting rid of hippies, then I'm getting rid of grunge."[14]

In spite of the professed disdain for the genres, some elements of both crept into the more enduring facets of Britpop. Noel Gallagher has since championed Ride and once stated that Nirvana's Kurt Cobain was the only songwriter he had respect for in the last ten years, and that he felt their music was similar enough that Cobain could have written "Wonderwall".[15] By 1996, Oasis's prominence was such that NME termed a number of Britpop bands (including The Boo Radleys, Ocean Colour Scene and Cast) "Noelrock", citing Gallagher's influence on their music.[16] Journalist John Harris described these bands, and Gallagher, as sharing "a dewy-eyed love of the 1960s, a spurning of much beyond rock's most basic ingredients, and a belief in the supremacy of 'real music'".[17]

The imagery associated with Britpop was equally British and working class. A rise in unabashed maleness, exemplified by Loaded magazine, binge drinking and lad culture in general, would be very much part of the Britpop era. The Union Jack became a prominent symbol of the movement (as it had a generation earlier with mod bands such as the Who) and its use as a symbol of pride and nationalism contrasted deeply with the controversy that erupted just a few years before when former Smiths singer Morrissey performed draped in it.[18] The emphasis on British reference points made it difficult for the genre to achieve success in the US.[19]

Origins and first years

[edit]

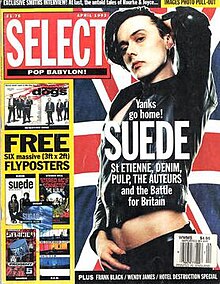

John Harris has suggested that Britpop began when Blur's fourth single "Popscene" and Suede's "The Drowners" were released around the same time in the spring of 1992. He stated, "[I]f Britpop started anywhere, it was the deluge of acclaim that greeted Suede's first records: all of them audacious, successful and very, very British."[20] Suede were the first of the new crop of guitar-orientated bands to be embraced by the UK music media as Britain's answer to Seattle's grunge sound. Their debut album Suede became the fastest-selling debut album in the history of the UK.[21] In April 1993, Select magazine featured Suede's lead singer Brett Anderson on the cover with a Union Flag in the background and the headline "Yanks go home!" The issue included features on Suede, the Auteurs, Denim, Saint Etienne and Pulp and helped start the idea of an emerging movement.[22][23]

Blur were involved in a vibrant social scene in London (dubbed "The Scene That Celebrates Itself" by Melody Maker) that focused on a weekly club called Syndrome in Oxford Street; the bands that met up were a mix of music styles, some would be labelled shoegazing, while others would go on to be part of Britpop.[24] The dominant musical force of the period was the grunge invasion from the United States, which filled the void left in the indie scene by the Stone Roses' inactivity.[23] Blur, however, took on an Anglocentric aesthetic with their second album Modern Life Is Rubbish (1993).

Blur's new approach was inspired by a tour of the United States in the spring of 1992. During the tour, frontman Damon Albarn began to resent American culture and found the need to comment on that culture's influence seeping into Britain.[23] Justine Frischmann, formerly of Suede and leader of Elastica (and at the time in a relationship with Albarn) explained, "Damon and I felt like we were in the thick of it at that point ... it occurred to us that Nirvana were out there, and people were very interested in American music, and there should be some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness."[25] John Harris wrote in an NME article just before the release of Modern Life is Rubbish: "[Blur's] timing has been fortuitously perfect. Why? Because, as with baggies and shoegazers, loud, long-haired Americans have just found themselves condemned to the ignominious corner labelled 'yesterday's thing'."[14] The music press also fixated on what the NME had dubbed the New Wave of New Wave, a term applied to the more punk-derivative acts such as Elastica, S*M*A*S*H and These Animal Men.

While Modern Life Is Rubbish was a moderate success, Blur's third album, Parklife, made them arguably the most popular band in the UK in 1994.[21] Parklife continued the fiercely British nature of its predecessor, and coupled with the death of Nirvana's Kurt Cobain in April of that year British alternative rock became the dominant rock genre in the country. That same year Oasis released their debut album Definitely Maybe, which broke Suede's record for fastest-selling debut album; it went on to be certified 7× Platinum (2.1 million sales) by the BPI.[21][26][27] Blur won four awards at the 1995 Brit Awards, including Best British Album for Parklife (ahead of Definitely Maybe).[28] In 1995, Pulp released the album Different Class which reached number one, and included the single "Common People". The album sold over 1.3 million copies in the UK.[29]

The term "Britpop" arose when the media were drawing on the success of British designers and films, the Young British Artists (sometimes termed "Britart") such as Damien Hirst, and on the mood of optimism with the decline of John Major's government, and the rise of the youthful Tony Blair as leader of the Labour Party.[30] After terms such as "the New Mod" and "Lion Pop"[31][32] were used in the press around 1992, journalist (and now BBC Radio 6 Music DJ) Stuart Maconie used the term Britpop in 1993 (though recounting the event in a BBC Radio 2 programme from 2020, he believed it may have been used in the 1960s, around the time of the British Invasion).[33] However, journalist and musician John Robb states he had used the term in the late 1980s in Sounds magazine to refer to bands such as the La's, the Stone Roses and Inspiral Carpets,[34] though many of these acts would be grouped under the Baggy, Madchester and indie-dance genres at the time.

It was not until 1994 that Britpop started to be used by the UK media in relation to contemporary music and events.[35] Bands emerged aligned with the new movement. At the start of 1995, bands including Sleeper, Supergrass and Menswear scored pop hits.[36] Elastica released their debut album Elastica that March; its first week sales surpassed the record set by Definitely Maybe the previous year.[37] The music press viewed the scene around Camden Town as a musical centre; frequented by groups like Blur, Elastica, and Menswear; Melody Maker declared "Camden is to 1995 what Seattle was to 1992, what Manchester was to 1989, and what Mr Blobby was to 1993."[38]

"The Battle of Britpop"

[edit]

A chart battle between Blur and Oasis, dubbed "The Battle of Britpop", brought Britpop to the forefront of the British press in 1995. The bands had initially praised each other but over the course of the year antagonisms between the two increased.[39] Spurred on by the media, they became engaged in what the NME dubbed on the cover of its 12 August issue the "British Heavyweight Championship" with the pending release of Blur's single "Country House" and Oasis' "Roll with It" on the same day. The battle pitted the two bands against each other, with the conflict as much about British class and regional divisions as it was about music.[40] Oasis were taken as representing the North of England, while Blur represented the South.[23] The event caught the public's imagination and gained mass media attention in national newspapers, tabloids and television news. NME wrote about the phenomenon:

Yes, in a week where news leaked that Saddam Hussein was preparing nuclear weapons, everyday folks were still getting slaughtered in Bosnia and Mike Tyson was making his comeback, tabloids and broadsheets alike went Britpop crazy.[41]

Billed as the greatest pop rivalry since the Beatles and the Rolling Stones,[42] it was spurred on by jibes thrown back and forth between the two groups, with Oasis dismissing Blur as "Chas & Dave chimney sweep music", while Blur referred to their opponents as the "Oasis Quo" in a deriding of their alleged unoriginality and inability to change.[43] In what was the best week for UK singles sales in a decade, on 20 August, Blur's "Country House" sold 274,000 copies against "Roll with It" by Oasis which sold 216,000, the songs charting at number one and number two, respectively.[44][45] Blur performed their chart topping single on the BBC's Top of the Pops, with the band's bassist Alex James wearing an 'Oasis' t-shirt.[46] However, in the long run Oasis became more commercially successful than Blur, at home and abroad.[43] In a 2019 interview, Oasis bandleader Noel Gallagher reflected on the chart battle between the two songs, both of which he saw as "shit", and suggested that a chart race between Oasis' "Cigarettes & Alcohol" and Blur's "Girls & Boys" would have had greater merit. He also noted that he and Blur frontman Damon Albarn – with whom Gallagher had enjoyed multiple musical collaborations during the 2010s[47][48] – were now friends.[49] Both men have noted that they do not discuss their 1990s rivalry,[49][50] with Albarn adding, "I value my friendship with Noel because he is one of the only people who went through what I did in the Nineties."[50] Noel Gallagher has also described Blur guitarist Graham Coxon as "one of the most talented guitarists of his generation."[51]

Peak and decline

[edit]

In the months following the chart battle, NME states, "Britpop became a major cultural phenomenon".[44] Oasis's second album, (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, sold over four million copies in the UK – becoming the fifth best-selling album in UK chart history.[52] Blur's third album in their 'Life' trilogy, The Great Escape, sold over one million copies.[53] At the 1996 Brit Awards, both albums were nominated for Best British Album (as was Pulp's Different Class), with Oasis winning the award.[54] All three bands were also nominated for Best British Group and Best Video, which were won by Oasis.[54] While accepting Best Video (for "Wonderwall"), Oasis taunted Blur by singing the chorus of the latter's "Parklife" and changing the lyrics to "shite life".[43]

Oasis' third album Be Here Now (1997) was highly anticipated. Despite initially attracting positive reviews and selling strongly, the record was soon subjected to strong criticism from music critics, record-buyers and even Noel Gallagher himself for its overproduced and bloated sound. Music critic Jon Savage pinpointed Be Here Now as the moment where Britpop ended; Savage said that while the album "isn't the great disaster that everybody says", he commented that "[i]t was supposed to be the big, big triumphal record" of the period.[23] At the same time, Blur sought to distance themselves from Britpop with their self-titled fifth album,[55] assimilating American lo-fi influences such as Pavement. Albarn explained to the NME in January 1997 that "We created a movement: as far as the lineage of British bands goes, there'll always be a place for us ... We genuinely started to see that world in a slightly different way."[56]

As Britpop slowed, many acts began to falter and broke up.[57] The sudden popularity of the pop group the Spice Girls has been seen as having "snatched the spirit of the age from those responsible for Britpop".[58] While established acts struggled, attention began to turn to the likes of Radiohead and the Verve, who had been previously overlooked by the British media. These two bands – in particular Radiohead – showed considerably more esoteric influences from the 1960s and 1970s that were uncommon among earlier Britpop acts. In 1997, Radiohead and the Verve released their respective albums OK Computer and Urban Hymns, both widely acclaimed.[57] Post-Britpop bands such as Travis, Stereophonics and Coldplay, influenced by Britpop acts, particularly Oasis, with more introspective lyrics, were some of the most successful rock acts of the late 1990s and early 2000s.[59]

Post-Britpop

[edit]

After Britpop the media focused on bands that may have been established acts, but had been overlooked due to focus on the Britpop movement. Bands such as Radiohead and the Verve, and new acts such as Travis, Stereophonics, Feeder and particularly Coldplay, achieved wider international success than most of the Britpop groups that had preceded them, and were some of the most commercially successful acts of the late 1990s and early 2000s.[62][63][64][65] These bands avoided the Britpop label while still producing music derived from it.[62][66] Bands that had enjoyed some success during the mid-1990s, but were not really part of the Britpop scene, included the Verve and Radiohead.[62] The music of most bands was guitar based,[67][68] often mixing elements of British traditional rock (or British trad rock),[69] particularly the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Small Faces[70] with American influences. Post-Britpop bands also used elements from 1970s British rock and pop music.[68] Drawn from across the UK, the themes of their music tended to be less parochially centred on British, English and London life, and more introspective than had been the case with Britpop at its height.[68][71][72][73] This, beside a greater willingness to woo the American press and fans, may have helped a number of them in achieving international success.[63] They have been seen as presenting the image of the rock star as an ordinary person, or "boy-next-door"[67] and their increasingly melodic music was criticised for being bland or derivative.[74]

The cultural and musical scene in Scotland, dubbed "Cool Caledonia" by some elements of the press,[75] produced a number of successful alternative acts, including the Supernaturals from Glasgow.[76] Travis, also from Glasgow, were one of the first major rock bands to emerge in the post-Britpop era,[62][77] and have been credited with a major role in disseminating and even creating the subgenre of post-Britpop.[78][79] From Edinburgh Idlewild, more influenced by post-grunge, produced three top 20 albums, peaking with The Remote Part (2002).[80] The first major band to break through from the post-Britpop Welsh rock scene, dubbed "Cool Cymru",[75] were Catatonia, whose single "Mulder and Scully" (1998) reached the top ten in the UK, and whose album International Velvet (1998) reached number one, but they were unable to make much impact in the US and, after personal problems, broke up at the end of the century.[65][81] Other Welsh bands included Stereophonics[82][83] and Feeder.[84][85]

These acts were followed by a number of bands who shared aspects of their music, including Snow Patrol from Northern Ireland and Elbow, Embrace, Starsailor, Doves, Electric Pyramid and Keane from England.[62][87] The most commercially successful band in the milieu were Coldplay, whose debut album Parachutes (2000) went multi-platinum and helped make them one of the most popular acts in the world by the time of their second album A Rush of Blood to the Head (2002).[60][88] Snow Patrol's "Chasing Cars" (from their 2006 album Eyes Open) is the most widely played song of the 21st century on UK radio.[86] Bands like Coldplay, Starsailor and Elbow, with introspective lyrics and even tempos, began to be criticised at the beginning of the new millennium as bland and sterile[89] and the wave of garage rock or post-punk revival bands, like the Hives, the Vines, the Libertines, the Strokes, the Black Keys and the White Stripes, that sprang up in that period were welcomed by the musical press as "the saviours of rock and roll".[90] However, a number of the bands of this era, particularly Travis, Stereophonics and Coldplay, continued to record and enjoy commercial success into the new millennium.[60][83][91] The idea of post-Britpop has been extended to include bands originating in the new millennium, including Razorlight, Kaiser Chiefs, Arctic Monkeys and Bloc Party,[92] seen as a "second wave" of Britpop".[63] These bands have been seen as looking less to music of the 1960s and more to 1970s punk and post-punk, while still being influenced by Britpop.[92]

Retrospective documentaries on the movement include The Britpop Story – a BBC programme presented by John Harris on BBC Four in August 2005 as part of Britpop Night, ten years after Blur and Oasis went head-to-head in the charts,[93][94] and Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop, a 2003 documentary film written and directed by John Dower. Both documentaries include mention of Tony Blair and New Labour's efforts to align themselves with the distinctly British cultural resurgence that was underway, as well Britpop artists such as Damien Hirst.[95]

Britpop revival

[edit]

At the beginning of the 2010s, a wave of new bands emerged that combined indie rock with the Britpop of the 1990s. Viva Brother launched an update on Britpop, dubbed “Gritpop,”[96][97] with their debut album Famous First Words, although they did not receive significant support from the music press. In 2012, All the Young released their debut album, Welcome Home. Later, bands such as Superfood[98] and the Australian band DMA's[99] joined the revival, with DMA’s debut album receiving favorable reviews.[100][101]

In the mid-2020s, a new group of artists began drawing inspiration from the energy and iconography of mid-90s Britain. Notable examples include Nia Archives, whose debut album Silence Is Loud features a Union Jack on its cover, and Dua Lipa, who explored Britpop influences in her album Radical Optimism. AG Cook’s triple album Britpop reimagines the genre’s aesthetic, featuring Charli XCX and a warped Union Jack cover. Rachel Chinouriri’s album What a Devastating Turn of Events notably incorporates Britpop influences, aiming to recreate the visual and sonic aesthetics of the Britpop movement. Chinouriri cited bands like Oasis and The Libertines as key inspirations.[102][103]

Terminology

[edit]Artists of the genre have dismissed the "Britpop" term. Oasis bandleader Noel Gallagher denied that the band were associated with the term: "We're not Britpop, we're universal rock. The media can take the Britpop and stick it as far up the back entry of the country houses as they can take it."[104] Blur guitarist Graham Coxon stated in the 2009 documentary Blur – No Distance Left to Run that he "didn't like being called Britpop, or pop, or PopBrit, or however you want to put it."[105] Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker also expressed his dislike for the term in an interview with Stephen Merchant on BBC Radio 4's Chain Reaction in 2010, describing it as a "horrible, bitty, sharp sound."[106]

In 2020, with attention turning to all "landfill indie" acts of the 2000s, Mark Beaumont of the NME argued that the term Britpop had been devalued, ignoring all the cultural aspects that had made the scene so important, with the term becoming a "catch-all" for "any band that played guitars in the 1990s."[107][108]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Rupert Till (2010). "In my beautiful neighbourhood: local cults of popular music". Pop Cult. A&C Black. p. 90. ISBN 9780826432360.

- ^ Michael Dwyer (25 July 2003). "The great Britpop swindle". The Age.

- ^ Nick Hasted (18 August 2005). "The summer of Britpop". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Elastica interview, The Face February 1995.

- ^ John Harris (2004). Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. Da Capo Press. p. 202. ISBN 030681367X.

- ^ Bennett, Professor Andy; Stratton, Professor Jon (2013). Britpop and the English Music Tradition. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-9407-2.

- ^ "Ray Davies: 'I'm not the godfather of Britpop … more a concerned uncle'". TheGuardian.com. 16 July 2015.

- ^ Dye, David (13 February 2007). "Paul Weller: A Britpop Titan Lives On". NPR. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Adam Ant and Marco Pirroni interview NME February 11 1995

- ^ Harris, pg. 385.

- ^ a b "Explore: Britpop". AllMusic. January 2011.

- ^ "40 Greatest One-Album Wonders: 13. The La's, 'The La's' (1990)". Rolling Stone. 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Britpop". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ a b John Harris (10 April 1993). "A shite sports car and a punk reincarnation". NME.

- ^ Matthew Caws (May 1996). "Top of the Pops". Guitar World.

- ^ Kessler, Ted. "Noelrock!" NME. 8 June 1996.

- ^ Harris, pg. 296.

- ^ Harris, pg. 295.

- ^ Simon Reynolds (22 October 1995). "RECORDINGS VIEW; Battle of the Bands: Old Turf, New Combatants". The New York Times.

- ^ The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock; John Harris; Harper Perennial; 2003.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "British Alternative Rock". AllMusic. Retrieved on 21 January 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010.

- ^ Ian Youngs (15 August 2005). "Looking back at the birth of Britpop". Bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b c d e Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop. Passion Pictures. 2004.

- ^ Harris, pg. 57.

- ^ Harris, pg. 79.

- ^ "Certified Awards Search". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Harris, pg. 178.

- ^ "The BRITs 1995". The BRIT Awards. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (17 September 2018). "The biggest selling Mercury Prize-winning albums revealed". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Stan Hawkins (2009). The British Pop Dandy: Masculinity, Popular Music and Culture. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 53. ISBN 9780754658580.

- ^ "The Battle of Britpop : 25 Years On". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "INTERVIEW: Cud". Shiiineon.com. 16 January 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "The Britpop Top 50 with Jo Whiley". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "'I had no idea they would be so big' – John Robb on Manchester music, Britpop, and being the first to interview Nirvana". Inews.co.uk. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Harris, pg. 201.

- ^ Harris, pg. 203–04.

- ^ Harris, pg. 210–11.

- ^ Parkes, Taylor. "It's An NW1-derful Life". Melody Maker. 17 June 1995.

- ^ Richardson, Andy. "The Battle of Britpop". NME. 12 August 1995.

- ^ Harris, pg. 230.

- ^ "Roll with the presses". NME. 26 August 1995.

- ^ "When Blur beat Oasis in the battle of Britpop". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Manning, Sean (2008). Rock and Roll Cage Match: Music's Greatest Rivalries, Decided. Crown/Archetype. p. 102.

- ^ a b c "Blur and Oasis' big Britpop chart battle – the definitive story of what really happened". Nme.com. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ Harris, pg. 235.

- ^ "The best of Blur at the BBC". BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher and Damon Albarn make history, performing together in London". Nme.com. 23 March 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ Luke Morgan Britton (23 March 2017). "Damon Albarn talks working with Noel Gallagher on new Gorillaz track 'We Got The Power'". Nme.com. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Noel Gallagher". Reel Stories. 23 June 2019. 9–10 minutes in. BBC Two. British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ a b Reilly, Nick (10 August 2018). "'We don't talk about our past': Damon Albarn opens up on close friendship with Noel Gallagher". NME. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop. Bonus interviews.

- ^ "The UK's biggest studio albums of all time". OfficialCharts.com. 13 October 2018. Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ^ BPI Certified Awards Search Archived 24 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine British Phonographic Industry. Note: reader must define "Search" parameter as "Blur".

- ^ a b "1996 Brit Awards: winners". Brits.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ Harris, pg. 321–22.

- ^ Mulvey, John. "We created a movement ... there'll always be a place for us". NME. 11 January 1997.

- ^ a b Harris, pg. 354.

- ^ Harris, p. 347–48.

- ^ Harris, pg. 369–70.

- ^ a b c "Coldplay", AllMusic, retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (4 July 2016). "The UK's 60 official biggest selling albums of all time revealed". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d e J. Harris, Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock (Da Capo Press, 2004), ISBN 0-306-81367-X, pp. 369–70.

- ^ a b c S. Dowling, "Are we in Britpop's second wave?" BBC News, 19 August 2005, retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ S. Birke, "Label Profile: Independiente" Archived 14 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Independent on Sunday, 11 April 2008, retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ a b J. Goodden, "Catatonia – Greatest Hits", BBC Wales, 2 September 2002, retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ S. Borthwick and R. Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1745-0, p. 188.

- ^ a b S. T. Erlewine, "Travis: The Boy With No Name", AllMusic, retrieved, 17 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Andy and Jon Stratton (2010). Britpop and the English Music Tradition. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 164, 166, 173. ISBN 978-0754668053.

- ^ "British Trad Rock", AllMusic, retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ A. Petridis, "Roll over Britpop ... it's the rebirth of art rock", The Guardian, 14 February 2004, retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ M. Cloonan, Popular Music and the State in the UK: Culture, Trade or Industry? (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-5373-0, p. 21.

- ^ A. Begrand, "Travis: The boy with no name", Pop matters, retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Whatever happened to our Rock and Roll" Archived 11 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Stylus Magazine, 2002-12-23, retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ A. Petridis, "And the bland played on", The Guardian, 26 February 2004, retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ a b S. Hill, Blerwytirhwng?: the Place of Welsh Pop Music (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-5898-8, p. 190.

- ^ D. Pride, "Global music pulse", Billboard, 22 Aug 1998, 110 (34), p. 41.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 1157.

- ^ M. Collar, "Travis: Singles", AllMusic, retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ S. Ross, "Britpop: rock aint what it used to be"[permanent dead link], McNeil Tribune, 20 January 2003, retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ J. Ankeny, "Idlewild", AllMusic, retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Catatonia", AllMusic, retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, p. 1076.

- ^ a b "Stereophonics", AllMusic, retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "Feeder", AllMusic, retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Feeder: Comfort in Sound", AllMusic, retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b "And the most-played song on UK radio is ... Chasing Cars by Snow Patrol". BBC News. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock (London: Rough Guides, 3rd end., 2003), ISBN 1-84353-105-4, pp. 310, 333, 337 and 1003-4.

- ^ Stephen M. Deusner (1 June 2009), "Coldplay LeftRightLeftRightLeft", Pitchfork, retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ M. Roach, This Is It-: the First Biography of the Strokes (London: Omnibus Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7119-9601-6, pp. 42 and 45.

- ^ C. Smith, 101 Albums That Changed Popular Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-537371-5, p. 240.

- ^ "Travis", AllMusic, retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b I. Collinson, "Devopop: pop Englishness and post-Britpop guitar bands", in A. Bennett and J. Stratton, eds, Britpop and the English Music Tradition (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), ISBN 0-7546-6805-3, pp. 163–178.

- ^ "Britpop Night on BBC Four - Tuesday 16 August". BBC Press Office. 18 July 2005. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Chater, David (16 August 2005). "Viewing guide". The Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ "Britpop movie holds première". News.bbc.co.uk. 3 March 2003.

- ^ "Breaking Out: Viva Brother". Spin. 13 June 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Britpop revivalists Viva Brother quietly announce their demise". The Independent. 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Daly, Rhian. "Superfood – 'Don't Say That'". NME. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Beaumont, Mark (27 August 2015). "DMA's review – Britpop revivalists evoke 90s euphoria". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Hills End by DMA's, retrieved 9 January 2019

- ^ "Did DMA's Have to Grow Up So Fast?". Popmatters.com. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Sarah (26 April 2024). "Mad fer it! The young musicians flying the flag for Britpop". GlobalNewsHub. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Butchard, Skye (26 April 2024). "Mad fer it! The young musicians flying the flag for Britpop". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Noël Gallagher on other genres". YouTube, Retrieved 27 March 2020

- ^ "Blur – No Distance Left to Run" (2009 documentary). YouTube. Retrieved 27 March 2020

- ^ "Stephen Merchant interviews Jarvis Cocker". BBC. Retrieved 27 March 2020

- ^ "The Top 50 Greatest Landfill Indie Songs of All Time". Vice.com. 27 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "The term 'landfill indie' is nothing but musical snobbery". Nme.com. 1 September 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Sources

- Harris, John. Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81367-X.

- Harris, John. "Modern Life is Brilliant!" NME. 7 January 1995.

- Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop. Passion Pictures, 2004.

- Till, Rupert. "In my beautiful neighbourhood: local cults of popular music". Pop Cult. London: Continuum, 2010.