Shuruppak

| Alternative name | Tell Fara |

|---|---|

| Location | Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Sumer |

| Coordinates | 31°46′39″N 45°30′35″E / 31.77750°N 45.50972°E |

| Type | archaeological site, human settlement |

| Area | 120 hectare |

| Height | 9 metre |

| History | |

| Periods | Jemdet Nasr period, Early Dynastic period, Akkad period, Ur III period |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1900, 1902-1903, 1931, 1973, 2016-2018 |

| Archaeologists | Robert Koldewey, Friedrich Delitzsch, Erich Schmidt, Harriet P. Martin |

Shuruppak (Sumerian: 𒋢𒆳𒊒𒆠 ŠuruppagKI, SU.KUR.RUki, "the healing place"), modern Tell Fara, was an ancient Sumerian city situated about 55 kilometres (35 mi) south of Nippur and 30 kilometers north of ancient Uruk on the banks of the Euphrates in Iraq's Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate. Shuruppak was dedicated to Ninlil, also called Sud, the goddess of grain and the air.[1]

"Shuruppak" is sometimes also the name of a king of the city, legendary survivor of the Flood, and supposed author of the Instructions of Shuruppak".

History

[edit]

Jemdet Nasr period

[edit]The earliest excavated levels at Shuruppak date to the Jemdet Nasr period about 3000 BC. Several objects made of arsenical copper were found in Shuruppak/Fara dating to the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 2900 BC). Similar objects were also found at Tepe Gawra (levels XII-VIII).[2]

Early Dynastic II

[edit]The city rose in importance and size, exceeding 40 hectares(0.4km2), during the Early Dynastic period.

In the Sumerian King List is a ruler, Ubara-Tutu, the last ruler "before the flood". In some versions he is followed by a son, Ziusudra.[3] In later versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh, a man named Utnapishtim, son of Ubara-Tutu, is noted to be king of Shuruppak. This portion of Gilgamesh is thought to have been taken from another literary composition, the Myth of Atrahasis.[4]

Early Dynastic III

[edit]The city expanded to its greatest extent at the end of the Early Dynastic III period (2600 BC to 2350 BC) when it covered about 100 hectares.[5]

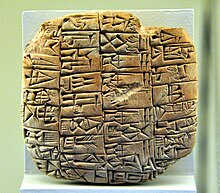

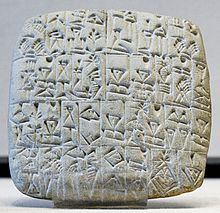

Cuneiform tablets from the Early Dynastic III period show a thriving, military oriented economy with links to cities throughout the region.[6] It has been proposed that Fara was part of a "hexapolis" with Lagash, Nippur, Uruk, Adab, and Umma, possibly under the leadership of Kish.[7][8]

Akkadian period

[edit]In the Akkadian Period (c. 2334–2154 BC), Shuruppak was ruled by a governor holding the title patesi. Like most cities on the Euphrates, it declined during the Akkadian Empire.[9] A clay cone from the Akkadian Empire period found at Shurappak read "Dada, governor of Suruppak: Hala-adda, gover[nor] of Suruppak, his son, laid the ... of the city gate of the goddess Sud".[10]

Governors: Dada; Hala-adda;

Ur III period

[edit]During Ur III period (c. 2112-2004 BC), the city was ruled by a governors (ensi2) appointed by Ur. One is known to be Ur-nigar, son of Shulgi, first rulers of Ur III. One of the tablets found at the site is dated by a year name to the beginning of the reign of Shu-Sin, next to last ruler of Ur III.[11] A few governors of Shurappak under the Ur III Empire are known from contemporary epigraphic remains, Ku-Nanna, Lugal-hedu, Ur-nigin-gar, and Ur-Ninkura.[12] In much later literary compositions several purported rulers are mentioned.

Middle Bronze I

[edit]In the 2020s BC, the Ur III Empire was hit by a major drought. It is thought to have been abandoned shortly around 2000 BC.

A Isin-Larsa cylinder seal and several pottery plaques which may date to early in the second millennium BC were found at the site.[13] Surface finds are predominantly Early Dynastic.[14] In the 2nd year of Enlil-bani (c. 1860–1837 BC), ruler of Isin, a sage of Nippur is recorded as leaving an herbal medicine at Shurappak.[15]

Flood Myth

[edit]The report of the 1930s excavation mentions a layer of flood deposits at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period at Shuruppak. Shuruppak in Mesopotamian legend is one of the "antediluvian" cities and the home of King Utnapishtim, who survives the flood by making a boat beforehand. Schmidt wrote that the flood story of the Bible, [16]

seems to be based on a very real event or a series of such, as suggested by the existence at Ur, at Kish, and now at Fara, of inundation deposits, which accumulated on top of human inhabitation. There is finally “the Noah story,” which may possibly symbolize the survival of the Sumerian culture and the end of the Elamite Jemdet Nasr culture.

The deposit is like that deposited by river avulsions, a process that was common in the Tigris–Euphrates river system.[17][18]

Archaeology

[edit]

Tell Fara extends about a kilometer from north to south. The total area is about 120 hectares, with about 35 hectares of the mound being more than three meters above the surrounding plain, with a maximum of 9 meters. The site consists of two mounds, one larger than the other, separated by an old canal bed as well as a lower town. It was visited by William Loftus in 1850.[19] Hermann Volrath Hilprecht conducted a brief survey in 1900.[20] He found "copper goatheads; a copper, pre-Sargonid sword; a lamp in the shape of a bird; a very archaic seal cylinder; a number of pre-Sargonid tablets, and 60 incised plates of mother of pearl".[16]

It was first excavated between 1902 and 1903 by Walter Andrae, Robert Koldewey and Friedrich Delitzsch of the German Oriental Society for eight months. They used a new "modern" system which involved excavating trenches 8 feet wide and 5 feet deep every few yards running across the entire width of the larger mound. If a building wall was found in a trench it was further explored. Preliminary identification of the site as Suruppak came from a Ur III period clay nail which mentioned "Haladda, son of Dada, the patesi of Shuruppak (written SU.KUR.RUki) repaired the ADUS of the Great Gate of the god Shuruppak (written dSU.KUR.RU-da)". Among other finds, 847 cuneiform tablets and 133 tablet fragments of Early Dynastic III period were collected, which ended up in the Berlin Museum and the Istanbul Museum. They included administrative, legal, lexical, and literary texts. Over 100 of the tablets dealt with the disbursement of rations to workers.[21] About a thousand Early Dynastic clay sealings and fragments (used to secure doors and containers) were also found. Most from cylinder seals but 19 were from stamp seals.[22] In 1903 the site was visited by Edgar James Banks who was excavating at the site of Adab, a four hour walk to the north. Banks took photographs of the German trenches and noted a 20 foot in diameter well, constructed with plano-convex bricks, in the center of the larger mound as well as an arched sewer, similarly constructed. The latter was where tablets were found. Banks also noted that the smaller mound held a cemetery.[23]

In 1926 it was visited by Raymond P, Dougherty during his archaeological survey of the region.[24] In March and April 1931, a joint team of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University of Pennsylvania excavated Shuruppak for a further six week season, with Erich Schmidt as director and with epigraphist Samuel Noah Kramer being prompted by reports of illicit excavations in the area. They were able to stratify the major occupation levels as Jemdat Nasr (Fara I), Early Dynastic (Fara II), and Ur III empire (Fara III). There was an "inundation event" between Fara I and Fara II.[16][25] The excavation recovered 96 tablets and fragments—mostly from pre-Sargonic times—biconvex, and unbaked. The tablets included reference to Shuruppak enabling confirmation of the sites original name.[26]

In 1973, a three-day surface survey of the site was conducted by Harriet P. Martin. Consisting mainly of pottery shard collection, the survey confirmed that Shuruppak dates at least as early as the Jemdet Nasr period, expanded greatly in the Early Dynastic period, and was also an element of the Akkadian Empire and the Third Dynasty of Ur.[27]

A surface survey and a full magnetometer survey of the site was completed was conducted between 2016 and 2018 by a team from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich led by Adelheid Otto and Berthold Einwag. The initial work was under the regional QADIS survey.[28] A drone was used to create a digital elevation model of the site.[29] The researchers found thousands of robber holes left by looters which had disturbed surface in many places, with the top several meters of the main mound destroyed.[30] They were able to use remains of the 900 meter long trench left by excavators in 1902 and 1903 to orient old excavation documents and aerial mapping with their geomagnetic results. Part of the site was inaccessible because of the spoil heaps from the excavations. A city wall was found (in Area A), which had been missed in the past.[30][31] A harbor and quay were also found.[32]

List of rulers

[edit]The following list should not be considered complete:

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic I period (c. 2900 – c. 2700 BC) | ||||||

| Predynastic Sumer (c. 2900 – c. 2700 BC) | ||||||

| ||||||

| 1st |

|

Ubara-Tutu 𒂬𒁺𒁺 |

Son of En-men-dur-ana (?) | Uncertain, reigned c. 2810 BC (18,600 years) |

| |

| ||||||

| 2nd |

|

Ziusudra 𒍣𒌓𒋤𒁺 |

Son of Ubara-Tutu (?) | Uncertain, r. c. 2800 BC (36,000 years) |

| |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (1 January 1987). The Harps that Once--: Sumerian Poetry in Translation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07278-5.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts, Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press, 1997 ISBN 0801433398 p167

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild (1939). The Sumerian King List (PDF). Chicago Illinois: The University of Chicago Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Maureen Gallery Kovacs, "TABLET XI", The Epic of Gilgamesh, edited by , Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 95-108, 1989

- ^ Leick, Gwendolyn (2002). Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026574-0.

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild and Moran, William L., "Early Political Development in Mesopotamia", Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 132-156, 1970

- ^ Cripps, Eric L. (2013). "Messengers from Šuruppak". Cuneiform Digital Library Journal. 2013 (3).

- ^ Pomponio, Francesco & Visicato Giuseppe, "Early Dynastic Administrative Tablets of Šuruppak", Napoli: Istituto Universitario Orientalo di Napoli, 1994

- ^ Marchetti, Nicolò, Al-Hussainy, Abbas, Benati, Giacomo, Luglio, Giampaolo, Scazzosi, Giulia, Valeri, Marco and Zaina, Federico, "The Rise of Urbanized Landscapes in Mesopotamia: The QADIS Integrated Survey Results and the Interpretation of Multi-Layered Historical Landscapes", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 214-237, 2019

- ^ Frayne, Douglas R. (1993). "Akkad". The Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113). University of Toronto Press. pp. 5–218. ISBN 0-8020-0593-4.

- ^ Sharlach, Tonia, "Princely Employments in the Reign of Shulgi", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-68, 2022

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Table III: List of Ur III Period Governors", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. xli-xliv, 1997

- ^ Martin, Harriet P. (1988). FARA: A reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak. Birmingham, UK: Chris Martin & Assoc. p. 44, p. 117 and seal no. 579. ISBN 0-907695-02-7.

- ^ Adams, Robert McCormick (1981). Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Fig. 33 compared with Fig. 21. ISBN 0-226-00544-5.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca, "The Babylonians and the Rational: Reasoning in Cuneiform Scribal Scholarship", In the Wake of the Compendia: Infrastructural Contexts and the Licensing of Empiricism in Ancient and Medieval Mesopotamia, edited by J. Cale Johnson, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 209-246, 2015

- ^ a b c Schmidt, Erich (1931). "Excavations at Fara, 1931". University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal. 2: 193–217.

- ^ Morozova, Galina S. (2005). "A review of Holocene avulsions of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and possible effects on the evolution of civilizations in lower Mesopotamia". Geoarchaeology. 20 (4): 401–423. doi:10.1002/gea.20057. ISSN 0883-6353. S2CID 129452555.

- ^ William W. Hallo and William Kelly Simpson (1971). The Ancient Near East: A History.

- ^ Loftus, William (1857). Travels and researches in Chaldæa and Susiana; with an account of excavations at Warka, the Erech of Nimrod, and Shúsh, Shushan the Palace of Esther, in 1849–52 (PDF). J. Nisbet and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hilprecht, Hermann Vollrat (1904). The Excavations in Assyria and Babylonia. Philadelphia: A.J. Holman – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Heinrich, Ernst; Andrae, Walter, eds. (1931). Fara, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Fara und Abu Hatab. Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

- ^ R.J.Matthews, "Fragments of Officialdom from Fara", Iraq, vol. 53, pp. 1–15, 1991

- ^ Banks, Edgar James (1912). Bismya; or The lost city of Adab : a story of adventure, of exploration, and of excavation among the ruins of the oldest of the buried cities of Babylonia (PDF). New York: G. P Putnam's Sons – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Dougherty, Raymond P, "An Archæological Survey in Southern Babylonia I", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 23, pp. 15–28, 1926

- ^ Kramer, Samuel N. (1932). "New Tablets from Fara". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 52 (2): 110–132. doi:10.2307/593166. JSTOR 593166.

- ^ Martin, Harriet P., "The Tablets of Shuruppak", in Le temple et le culte, Compte rendu de la vingtième Recontre Assyriologique Internationale, Leiden, pp. 173-182, 1975

- ^ Martin, Harriet P. (1983). "Settlement Patterns at Shuruppak". Iraq. 45 (1): 24–31. doi:10.2307/4200173. JSTOR 4200173. S2CID 130046037.

- ^ Marchetti, N., Einwag, B., Al-Hussainy, A., Luglio, G., Marchesi, G., Otto, A., Scazzosi, G., Leoni, E., Valeri, M. and Zaina, F., "QADIS. The Iraqi-Italian 2016 Survey Season in the South-Eastern Region of Qadisiyah", Sumer 63, pp. 63−92, 2017

- ^ Otto, A., & Einwag, B., "The survey at Fara - Šuruppak 2016-2018", In Otto, A., Herles, M., Kaniuth, K., Korn, L., & Heidenreich, A. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 2. Wiesbaden, pp. 293–306. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2020

- ^ a b Otto, A., Einwag, B., Al-Hussainy, A., Jawdat, J.A.H., Fink, C. and Maaß, H., "Destruction and Looting of Archaeological Sites between Fāra / Šuruppak and Išān Bahrīyāt / Isin: Damage Assessment during the Fara Regional Survey Project FARSUP", Sumer 64, pp. 35−48, 2018

- ^ Hahn, Sandra E.; Fassbinder, Jörg W. E.; Otto, Adelheid; Einwag, Berthold; Al-Hussainy, Abbas Ali (2022). "Revisiting Fara: Comparison of merged prospection results of diverse magnetometers with the earliest excavations in ancient Šuruppak from 120 years ago". Archaeological Prospection. 29 (4): 623–635. doi:10.1002/arp.1878. S2CID 252827382.

- ^ Fassbinder, Jörg; Hahn, Sandra; Wolf, Marco (2023). "Prospecting in the marshland: the Sumerian city Fara— Šuruppak (Iraq)" (PDF). In Wunderlich, Tina; Hadler, Hanna; Blankenfeldt, Ruth (eds.). Advances in On– and Offshore Archaeological Prospection: Proceedings. 15th International Conference on Archaeological Prospection. Kiel University Publishing. doi:10.38072/978-3-928794-83-1/p7. ISBN 978-3-928794-83-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrae, W., "Aus einem Berichte W. Andrae's über seineExkursion von Fara nach den südbabylonischen Ruinenstätten(TellǏd, Jǒcha und Hamam)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 16–24, 1902 (in german)

- Andrae, W., "Die Umgebung von Fara und Abu Hatab (Fara,Bismaja, Abu Hatab, Hˇetime, Dschidr und Juba’i)", Mitteilungen derDeutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 24–30, 1902 (in german)

- Andrae, W., "Ausgrabungen in Fara und Abu Hatab. Bericht über dieZeit vom 15. August 1902 bis 10. Januar 1903", Mitteilungen derDeutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,17, pp.4–35, 1903 (in german)

- Cavigneaux, A., "Deux noveaux contrats de Fāra", in I. Arkhipov – L. Kogan – N. Koslova (eds), The Third Millennium. Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik (Cuneiform Monographs 50), Leiden, pp. 240–258, 2020

- Deimel, Anton (1922). Die Inschriften von Fara, Vol. I: Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen (in German). Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

- [1]Anton Deimel, "Die Inschriften von Fara, Vol. II: Schultexte aus Fara", Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, Berlin, Wissenschaftliche Ver6ffentlichungen, Vol. XLIII, Leipzig, 1923

- Anton Deimel, "Die Inschriften von Fara, Vol. III: Wirtschaftstexte aus Fara", Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, Berlin. Wissenschaftliche Ver6ffentlichungen, Vol. XLV, Leipzig, 1924

- Edzard, D. O., "Fara und Abu Salabih. Die 'Wirtschaftstexte'", ZA 66, pp. 156-195, 1976

- Edzard, D. O., "Die Archive von Šuruppag (FĀRA): Umfang und Grenzen der Auswertbarkeit", in E. Lipiñski, State and Temple Economy in the Ancient Near East. Vol. 1. OLA 5, Leuven: Department Oriëntalistiek, pp. 153-169, 1979

- Foster, B., "Shuruppak and the Sumerian City State", in L. Kogan, N. Kosolova et.al. (eds.), Babel and Bibel 2. Memoriae Igor M. Diakonoff Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp.71–88, 2005

- [2]Gori, Fiammetta, "Numeracy in early syro-mesopotamia. A study of accounting practices from Fāra to Ebla", University of Verona Disertation, 2024

- R. Jestin, "Tablettes sumériennes de Shuruppak conserves au Musée de Stamboul" Paris, 1937

- Jestin, R., "Nouvelles tablettes sumériennes de Suruppak au musée d'Istanbul", Paris, 1957

- Koldewey, R., "Acht Briefe Dr. Koldewey's (teilweise im Auszug)(Babylon, Fara und Abu Hatab)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,15, pp. 6–24, 1902 (in german)

- Koldewey, R., "Auszug aus fünf Briefen Dr. Koldewey's (Babylon,Fara und Abu Hatab)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,16, pp. 8–15, 1902 (in german)

- Krebernik, M., "Die Texte aus Fāra und Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ", In: J. Bauer, R. K. Englund and M. Krebernik (eds.), Mesopotamien. Späturuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. OBO 160/1 (Freiburg–Göttingen), pp. 235−427, 1998

- Krebernik, Manfred, "Prä-Fara-zeitliche Texte aus Fara", Babel und Bibel 8: Studies in Sumerian Language and Literature: Festschrift Joachim Krecher, edited by Natalia Koslova, E. Vizirova and Gabor Zólyomi, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 327-382, 2014

- Lambert, Maurice, "Quatres nouveaux contrats de l’époque de Shuruppak", in: Manfred Lurker (ed.), Beiträge zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion des Alten Orients, In memoriam Eckhard Unger, Baden-Baden, pp. 27–40, 1971

- M. Lambert, "La Periode pr6sargonique, la vie economique a Shuruppak", Sumer 9, pp. 202-205, 1953

- H. P. Martin et al., "The Fara Tablets in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology", Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2001 ISBN 1-883053-66-8

- Nöldeke, A., "Die Rückkehr unserer Expedition aus Fara", Mitteilun-gen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft,17, pp. 35–44, 1903 (in german)

- Pomponio, Francesco, "Notes on the Fara Texts", Orientalia 53.1, pp. 1-18, 1984

- Sallaberger, W., "Fara Notes, 1: Administrative lists identified as dub bar and dub gibil", NABU 2022/2, pp. 98–99, 2022

- Steible, H. and Yildiz, F., "Wirtschaftstexte aus Fara II", WVDOG 143, Wiesbaden, 2015

- Steible, H. – Yıldız, F., "Kupfer an ein Herdenmat in Šuruppak?", in Ö. Tunca – D. Deheselle (eds), Tablettes et images aux pays de Sumer et Akkad. Mélanges offerts à Monsieur H. Limet, Liège, pp. 149-159, 1996

- Steible, H. – Yıldız, F., "Lapislazuli-Zuteilungen an die “Prominenz” von Šuruppak", in S. Graziani (ed.), Studi sul Vicino Oriente Antico dedicati alla memoria di Luigi Cagni, Napoli, pp.985–1031, 2000

- G. Visicato, "The Bureaucracy of Shuruppak : Administrative Centres, Central Offices, Intermediate Structures and Hierarchies in the Economic Documentation of Fara", Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 1995

- Visicato, Giuseppe, "Some Aspects of the Administrative Organization of Fara", Orientalia, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 94–99, 1992

- Visicato, G. – Westenholz, A., "A New Fara Contract", SEL 19, pp. 1–4, 2002

- Wencel, M. M., "New radiocarbon dates from southern Mesopotamia (Fara and Ur)", Iraq, 80, pp. 251-261, 2018