Teatro San Cassiano

| Teatro Tron | |

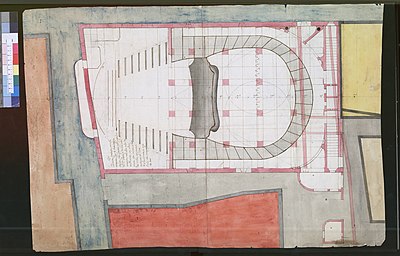

Teatro San Cassiano (1637): historically-informed visualisation | |

| |

| Location | Venezia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°26′18.64″N 12°19′49.33″E / 45.4385111°N 12.3303694°E |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1637 |

| Demolished | 1812 |

The Teatro San Cassiano (or Teatro di San Cassiano and other variants) was the world's first public opera house, inaugurated as such in 1637 in Venice. The first mention of its construction dates back to 1581.[1] The name with which it is best known comes from the parish in which it was located, San Cassiano (Saint Cassian), in the Santa Croce district (‘sestiere’) not far from the Rialto.

The theatre was owned by the Venetian Tron family and was the first ‘public’ opera house in the sense that it was the first to open to a paying audience. Until then, public theatres (i.e., those operating on a commercial basis) had staged only recited theatrical performances (commedie)[2][3] while opera had remained a private spectacle, reserved for the aristocracy and the courts. The Teatro San Cassiano was, therefore, the first public theatre to stage opera and in so doing opened opera for wider public consumption.

In 2019 a project, conceived by the English entrepreneur and musicologist Paul Atkin, was announced to reconstruct in Venice the Teatro San Cassiano of 1637[4] as faithfully as academic research and traditional craftmanship will allow, complete with period stage machinery and moving stage sets. The project aims to establish the reconstructed Teatro San Cassiano as a centre for the research, exploration and staging of historically informed Baroque opera.

Sixteenth century

[edit]The first information relating to a theatre on this site dates back to 1581. The Tron family theatre for commedie is referenced both in a letter sent by Ettore Tron to Duke Alfonso II d’Este, dated 4 January 1580 more veneto (i.e., 1581), and in Francesco Sansovino’s, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare,[5] in which two theatres in the parish of San Cassiano are mentioned: according to some historians, and based on the roughly rectangular shape of the plot of land on which it stood, the Tron theatre would appear to have been the “egg-shaped” one, with the Michiel in turn being the “round” one.[6] In the cited letter, Tron writes of “expenditure of great significance for the recitation of comedies”, but he also hints at the popularity of his venture:

— Ettore Tron to duke Alfonso II d’Este, 4 gennaio 1580 more veneto, transcribed I Teatri del Veneto cit., Tomo I, p. 126

Other than suggesting that the theatre was well received, this also confirms that theatre-boxes, which would later constitute one of the key architectural elements of the théâtre à l'italienne (an Italianate opera house), were already present in this first incarnation of the venue. This too is confirmed in a letter from Venice by Paolo Mori (agent of the Duke of Mantua), dated 7 October 1581, which mentions the “boxes of those two purpose-built venues”.[7][8] Additionally, in Antonio Persio's Trattato de’ Portamenti (1607), within a passage referring to the years preceding 1593—and in reference seemingly to either the Tron theatre or the Michiel theatre—the author writes that the nobles “had rented almost all the boxes”.[9][10]

With regard to the date of construction of the Tron theatre, and the presence therein of boxes (an innovative feature from both an architectural-theatrical and commercial point of view), it is noted that somewhat opportunely in 1580 a radical change occurred in the language of the Council of Ten relating to these theatrical venues, as for the first time a formula had been attested which implies concerns relating to their structural solidity in that they had to be “strong and safe so that no collapse can happen”.[11] Therefore, it would appear that the innovation given by the introduction of boxes as an integral part of the structure of a theatrical building gave rise within the Council of Ten to safety concerns. This would explain why the Council ordered that experts had to verify solidity in advance to eliminate collapses and consequent accidents or worse.

The Tron theatre (together with the one owned by the Michiel family, located near the Grand Canal) was subsequently closed in 1585 by order of the Council of Ten and emptied of any wooden element that had to do with the theatrical nature of the place;[12] the Tron theatre (i.e. the Teatro San Cassiano) was then reopened probably after 1607.[13][14]

Seventeenth century

[edit]The construction of the theatre in 1637: birth of the world's first public opera house

[edit]Archive documents refer with some continuity to the use of the Teatro San Cassiano for theatrical performances throughout the 1610s.[15] In 1629 and 1633, two fires destroyed the theatre. No known archival documents mention the theatre in the two years 1634–1635.[16]

In 1636, the Tron brothers (Ettore and Francesco, of the ‘branch’ of the San Benetto family) appear to have communicated to the authorities their intention to open a “Theatre for music”, thus clarifying from the outset its function as an opera house. This, in itself, marks a critical turning point in the history of opera: a theatre built specifically to stage music.

This is revealed in a document dated 2 May 1636, reportedly uncovered by Remo Giazotto in the late 1960s but no longer traceable since at least the mid-1970s:[17][18][19]

With reference to the information given to these Illustrious Magistrates by the Noblemen Tron of San Benetto regarding the intention of opening a Theatre for music, as practiced in some places for the delight of distinguished audiences [...]

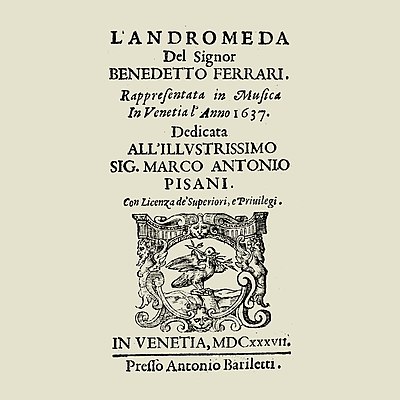

No image of the theatre of 1637 is extant today: neither of the outside nor of the inside. What is well known is that the Teatro San Cassiano was inaugurated in 1637 with the performance of L’Andromeda by Francesco Manelli (music) and Benedetto Ferrari (libretto). The dedication, dated 6 May 1637, specifies that the opera “had been reborn on stage two months ago”.[20]

The historical significance of this event is incalculable, as is the commercial practice established of purchasing of an entrance ticket by each spectator; a concept destined for global diffusion, but which occurs here as public opera for the first time. Indeed, the Teatro San Cassiano can, therefore, be seen as the economic-architectonic prototype of the Italian opera house destined to enjoy enormous fortune over the following centuries.[21]

The structure of the theatre of 1637

[edit]Given the total absence of images relating to this phase of Teatro San Cassiano's history, a document stipulated by the Notary Alessandro Pariglia, dated 12 February 1657 more veneto, offers significant insight with regard to the internal structure of the auditorium. In it, the Notary records that before this date there were a total of 153 boxes in the theatre, but that now there remained 102; no reason is given and whether he is referring to the number of boxes in use or their number in total is not clear.

The same number of 153 was later described by the French Jacques Chassebras de Cramailles in 1683, who wrote in the Mercure Galant that “the theatre of San Cassiano [...] has five tiers of boxes and 31 in each tier”.[22] Noting the characteristics of Venetian theatres in the seventeenth century, it is therefore logical to conclude that the total of 153 boxes is made up of four tiers of 31 boxes each, plus a first “ground-floor” tier, known as the ‘Pepiano’, of 29 boxes with two side-entrances to the “platea” (orchestra stalls). This number matches precisely that recorded, decades later, by the Venetian architect, Francesco Bognolo, when he carried out surveys of all Venetian theatres (plus one in Padua) prior to 7 June 1765.[23] In his list of measurements relating to what Bognolo calls the “old Teatro San Cassiano” (dating back to 1696 or further to 1670), the architect specifies “total boxes: number 31 per tier”, exactly as cited by Chassebras. This total of 153 boxes therefore runs through the history of the theatre from at least the 1650s to the mid-eighteenth century. Given that the first extant testimony dates back to February 1657 more veneto (i.e., February 1658), and in noting that there were no known remakes or renovations between its inauguration in 1637 and 1658, and that further the plot of land on which the theatre stood, as far as is known, remained unvaried from 1637 until the 1760s (it measured c. 27 metres by 18.5 metres), it is reasonable to conclude that from the outset the theatre of 1637 had 153 boxes over five tiers (thus, a ground-floor ‘Pepiano’ tier, plus first, second, third and fourth ‘ordini’).

In this regard, and to cite contemporary examples even if in remarkably different contexts, both the temporary theatre built for the production of L’Ermiona (Padua, 1636)[24] and the theatre in the Great Hall of the Palazzo del Podestà (Bologna, 1639)[25] each presented a total of five tiers of boxes, albeit those of Padua are recorded as being of larger (wider) boxes or “loggias”. As such, the structure of five superimposed tiers is attested in those years beyond Venice and constitutes a type of theatre congruent with what is known, to date, of the Teatro San Cassiano of 1637.

Artistic life

[edit]As for the artistic life of the theatre, after the performance of La maga fulminata (1638), again by Francesco Manelli and Benedetto Ferrari, from 1639 onwards Francesco Cavalli became the theatre's and Venice's chief protagonist. Cavalli has become one of the most studied and significant opera composers of the seventeenth century because “Cavalli’s operas [...] are not only relevant qualitatively, but they also remain among the few about which sufficient documentation has been preserved. Indeed, it should be pointed out that with regard to the first 25 years of Venetian opera production, by comparison to the approximately one hundred surviving printed librettos, only about thirty scores, all handwritten, remain extant today, of which two thirds are Cavalli’s”.[26] His Le nozze di Teti e di Peleo (1639) remains the first fully extant opera for the Teatro San Cassiano. This was followed by Gli amori d'Apollo e di Dafne (1640), La Didone (1641), La virtù de' strali d'Amore (1642), L'Egisto (1643), L'Ormindo (1644), La Doriclea (1645), Il Titone (1645), Giasone (1649), L'Orimonte (1650), Antioco (1658), and Elena (1659). Other significant composers, active at the Teatro San Cassiano in the seventeenth century, include Pietro Andrea Ziani, Marc’Antonio Ziani, Antonio Gianettini and Tomaso Albinoni. Indeed, it was Gianettini's opera L’ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone (Modena, 1692), which became the first Teatro San Cassiano co-production of the reconstruction project when it received its modern-day premiere in September 2018, in the castle theatre of Český Krumlov, conductor Ondřej Macek.[27]

Eighteenth century

[edit]Building and artistic life

[edit]There is no evidence relating to structural works having occurred during the first half of the eighteenth century.

On the other hand, opera production continued with some consistency at least until the middle of the century, thanks in particular to the long-lasting collaboration with Tomaso Albinoni; other noted composers who staged their operas at the Teatro San Cassiano in this era were Antonio Pollarolo, Francesco Gasparini, Carlo Francesco Pollarolo, Antonio Lotti, Gaetano Latilla, Baldassare Galuppi.[28]

Bognolo’s surveys and the theatre of 1763

[edit]

As previously noted, prior to 1765, Francesco Bognolo—the architect in charge of the design of the ‘new’ Teatro San Cassiano—took measurements of “all the theatres in Venice, as well as the one in Padua”.[29] Among these, the precise measurements relating to the ‘old’ Teatro San Cassiano appear. This theatre was characterised by reduced dimensions: the proscenium, for example, was a little wider than 8 metres, while the stage had an average depth of 6.5 metres. The boxes were extremely limited in size, at least by comparison to those of the nineteenth century to which we are now accustomed, and their widths ranged from about 95 centimetres to c. 120 centimetres in the ‘pergoletto di mezzo’ (central box). The recorded height of the boxes of the ‘primo ordine’ (second tier) was slightly less than 2.10 metres, while for those of the ‘terzo ordine’ (thus, the fourth tier) were just over 1.80 metres. As for the ‘new’ Teatro San Cassiano, inaugurated with La morte di Dimone (1763), music by Antonio Tozzi and libretto by Johann Joseph Felix von Kurz and Giovanni Bertati, the main difference was with regard the deeper stage, achieved by the extending the length of the theatre by demolishing two small houses which, with reference to the ‘old’ Teatro San Cassiano, stood against its end wall located a few metres from the outer curve of the boxes. In the ‘new’ Teatro San Cassiano, the average depth of the stage was slightly less than 9.5 metres, therefore approximately 3 metres more than its predecessor; the boxes were also a little wider than that of the late-seventeenth-century Teatro San Cassiano: suffice to compare the width the proscenium boxes of the ‘old’ theatre at 104 centimetres against 139 centimetres in the ‘new’ theatre.

Last years and demolition

[edit]In 1776, if Giacomo Casanova is to be taken in good faith, the Teatro San Cassiano had become a place where “women of the underworld and prostitute young men commit in the boxes of the fifth tier those crimes that the Government, in tolerating them, wants at least not to be exposed to the sight of others”, a description that has led to suppose an early state of degradation and decay.[30]

The last known season was that of 1798, during which two operas were performed: La sposa di stravagante temperamento (as we read in the libretto, “the music is by Mr Pietro Guglielmi, Neapolitan chapel master. The scenario will be entirely invented and directed by Mr Luigi Facchinelli, from Verona”)[31] and Gli umori contrari (music by Sebastiano Nasolini, libretto by Giovanni Bertati).

The last word should go to I teatri del Veneto: “In 1805, the French decided to close it definitively. The entire building was demolished in 1812 to make room for houses [...]. Today, the area of the Teatro San Cassiano has become the Albrizzi garden”.[32]

The reimagination and reconstruction project

[edit]The ongoing project to reconstruct the Teatro San Cassiano of 1637 in Venice has been conceived, directed and financed by Paul Atkin, founder and CEO of the Teatro San Cassiano Group Ltd. The project was first devised by Atkin in 1999, but research into the feasibility of rebuilding the original theatre of 1637 in Venice began in earnest in April 2015. This led to the incorporation of the Teatro San Cassiano Group in early May 2017 (near the anniversary of the libretto of L’Andromeda, whose dedication is dated 6 May 1637) and the official launch of the project in June 2019 through an international conference, an exhibition and a concluding concert held in Venice: ‘Teatro San Cassiano: need, solution, opportunity’. The project has received the formal support of the Comune of Venice. The Teatro San Cassiano Group has announced that a preferred site has been identified and that the appropriate technical-architectural studies are in process.[33]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. pp. 97–149.

- ^ Mangini, Nicola (1974). I teatri di Venezia. Milan: Mursia. p. 35.

- ^ Glixon, Beth L.; Glixon, Jonathan E. (2006). Inventing the Business of Opera. The Impresario and His World in Seventeenth-Century Venice. Oxford-New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Wagstyl, Stefan (28 November 2019). "The Briton dreaming of rebuilding Venice's long-lost opera treasure". Financial Times.

- ^ Published by Iacomo Sansovino, Venice, 1581, p. 75

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 98.

- ^ D'Ancona, Alessandro (1891). Origini del teatro italiano. Vol. 2. Turin: Loescher. p. 452.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 93.

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. (Autumn 2002). "The Short, Lascivious Lives of Two Venetian Theaters, 1580-85". Renaissance Quarterly. 55, N. 3 (3): 936–968, 965. doi:10.2307/1261561. JSTOR 1261561. S2CID 155751114.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 95.

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. (Autumn 2002). "The Short, Lascivious Lives of Two Venetian Theaters, 1580-85". Renaissance Quarterly. 55, N. 3: 959.

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. (Autumn 2002). "The Short, Lascivious Lives of Two Venetian Theaters, 1580-85". Renaissance Quarterly. 55, N. 3: 954, 963.

Within 15 days they must dismantle entirely the boxes, scenery, and other movable things in the places they have constructed to perform Comedies, so that nothing remains for that effect (document of 14 January 1585 more veneto)

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. XXVIII.

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. (2018). Inventing the Opera House. Theater Architecture in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. pp. 126–130.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 100.

- ^ Giazotto, Remo (July–August 1967). "La guerra dei palchi". Nuova Rivista Musicale Italiana. Year 1, n. 2: 245–286:252–253.

- ^ Mangini, Nicola (1974). I teatri di Venezia. Milan: Mursia. p. 37, footnote 21.

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. (2018). Inventing the Opera House. Theater Architecture in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 299, footnote 24.

- ^ L’Andromeda, Antonio Bariletti, Venice, 1637, p. 3.

- ^ Bianconi, Lorenzo (1987). Music in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 183.

the Venetian-type theatre […] comes to represent something of an economic and architectural prototype for Italy and Europe as a whole. At least architecturally, this prototype still survives essentially unchanged […].

- ^ «Le Théatre de S. Cassian est […] à cinq rangs de Pales, et 31. à chaque rang»; Jacques Chassebras de Cramailles, Mercure Galant, March 1683, p. 288.

- ^ Archivio di Stato, Venice, Giudici del Piovego, busta 86.

- ^ «Five tiers of loggias circled all around, one superimposed upon the other, with parapets in front of the marble balustrades; the spaces, comfortable for sixteen spectators, were separated by some partitions that presented externally as columns, from which silver wooden arms protruded outward to support the double candlestick holders that illuminated the theatre»; L’Ermiona, Padua, Paolo Frambotto, 1638, p. 8. Punctuation has been modified to make clearer the meaning of the text.

- ^ The miniature that portrays it (preserved in the State Archives of Bologna, Anziani Consoli, Insignia, Vol. VII, C. 15a, 1639) can be seen for example in Eugene J. Johnson, Inventing the Opera House cit., p. 171.

- ^ Staffieri, Gloria (2014). L'opera italiana. Dalle origini alle riforme del secolo dei Lumi (1590-1790). Rome: Carocci. p. 121.

- ^ See Paul Atkin, Opera Production in Late Seventeenth-Century Modena: The Case of L’ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone (1692), Royal Holloway College (University of London), supervisor Tim Carter, 2010. The premiere was the result of a synergy between the local organising bodies and the Teatro San Cassiano.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. pp. 144–147.

- ^ Cited from Archivio di Stato, Venice, Giudici del Piovego, busta 86.

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 105.

- ^ Venice, Antonio Rosa [1798], p. 2 (unnumbered).

- ^ Mancini, Franco; Povoledo, Elena; Muraro, Maria Teresa (1995). I Teatri del Veneto - Venezia. Vol. Tomo 1. Venice: Corbo e Fiore. p. 105.

- ^ Kington, Tom (15 July 2019). "British opera lover to rebuild the world's first house". The Times. Retrieved 29 December 2020.