Talk:Low-carbon diet

| This article is rated Start-class on Wikipedia's content assessment scale. It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

US-centric

[edit]Its horribly US-centric William M. Connolley (talk) 22:41, 20 June 2008 (UTC)

Then put a world view on it.'''Aryeonos''' (talk) 23:37, 9 February 2010 (UTC)

grain vs. grass

[edit]I've added a distinction between CAFO-produced and grass-fed meat, as the existing text implied that all meat was grain-fed, which isn't the case. I'm also curious about the dairy argument as this isn't specifically referenced, and I'm not sure what the GhGe contribution is from dairy herds relative to beef cattle - haven't seen this highlighted in anything I've read. In any case I'd have thought cheese was less harmful than milk (at least) in terms of transport, since it has significantly lower water content. However, not clued up enough to feel confident of editing this. Helliebellie (talk) 07:05, 24 June 2008 (UTC)

The vegetarian slant in this article is absolutely preposterous. Livestock don't cause the large amount of crops required in their fatting to magically vanish into them as they grow, leaving behind nothing but the butchered animal upon slaughter. In addition, they convert their feed to a variety of necessary agricultural products throughout their life, such as droppings and other litter, which are primarily used as soil conditioner and plant food (for crops which, obviously, end up served on the same plate as the animal.) I've even heard of some large-scale operations which capture gas emissions to use as fuel. 72.235.10.209 (talk) 17:19, 4 April 2009 (UTC)

- While it is true that livestock themselves are blameless in this debate, the simple biological fact is that cattle, poultry, goats, sheep, and pigs (the big 5 livestock animals in Western agriculture) are all grazing animals - none of them are natural consumers of grain-based diets. Where this article tries to point out that pasture-raised meat, eggs, and dairy are healthier and more sustainable, the issue at hand shouldn't be health concerns really, but rather the sustainability of current livestock ag practices - which ARE unsustainable no matter how you look at it. Methane capture is a coping mechanism to stem emissions of greenhouse gases; manure as fertilizer is a fact of nature whether livestock are grain fed or pastured. There's no need for a slant in favor of a diet; what's at issue is the sustainability of current ag practices compared with a return to old-school livestock practices that are more in line with the physiological requirements of the animals being raised. As a former vegan, I now eat pastured organic meats, eggs, and dairy when I can, and I still support veganism as a positive option for reducing one's carbon footprint. To me, it's all about what one person wants to choose to do to lower their impact on the Earth. Jaybird vt (talk) 00:00, 9 July 2009 (UTC)

A random comment with intent to make a coherent contribution in the future -- this article is pretty inconsistent with any peer-reviewed study on the topic of GHG emissions in the food system. There are good summary papers out there, including Tara Garnett's 2008 work for the Food Climate Research Network in the U.K. ("Cooking up a Storm," google it) and a recent (2010) article from the Leopold Centre and Dalhousie University (Pelletier is the lead author I believe) which offer some substantiated data. The two most notable inconsistencies between the peer-reviewed research and this article:

- 1 -- Grass-fed beef creates more GHG emissions than grain-fed. Yes, even taking into account the entire production, transportation, transformation, and processing life cycle of feed grains and also taking into consideration that the permanent rangelands and pasturelands, while storing tremendous amounts of Carbon worldwide, are likely saturated (in equilibrium) so aren't typically sequestering additional C as cattle graze them. While grass is indeed what cattle evolved to eat, and they are healthier eating it (no acidosis, etc), and it is arugably a more humane, and for lack of a better word, "natural" way to raise cattle, pasture / range systems produce more GHG emissions overall than feed grain / feedlot systems. (Personally, as I'm not keen on feedlot systems for a number of reasons, this finding doesn't sit well with me, but my distate for it doesn't make it incorrect.)

- 2 -- Transportation and "food miles" are, from a system-wide perspective, very minor players in GHG emissions. Take a look at the Matthews and Weber study that came out of Carnegie-Mellon in 2008 (I think) and any ISO-compliant LCA completed on food items since the standard was released in 2006 -- food miles mean very little in terms of their direct contributions to GHG in the food system. The food miles that may matter the most are the ones that are logged in a consumer's car trip from the grocery store to their home. 1 bag of groceries in an SUV driven 10km could be higher impact than a loaded semi trailer driving from Mexico to Seattle, in terms of GHG emission per weight of food. If you want a snark-laden take on it, read through http://peakoildebunked.blogspot.com/2009/10/426-local-food-guzzles-more-fuel-than.html

There's really only two rules for a low-carbon diet that make a surefire and significant difference:

- 1 -- Grass fed or grain fed, organic or conventional, you can't escape it: animal products, especially ruminant products, are GHG-intensive. Fill up on plants. If you like meat, enjoy it as a treat.

- 2 -- The most important "food miles" are probably the ones from the grocery store to your house. Cut back on those before worrying about how far away the farm was.

Oh yeah, and linking to "vertical farming" implies that a climate-controlled, artificially-lit intensive hydroponic system is a low-carbon food production system. And that's just plain laws-of-thermodynamics-defying wacky.

So much editing to do... —Preceding unsigned comment added by 173.183.79.92 (talk) 08:50, 29 June 2010 (UTC)

Removed unsourced claims

[edit]I removed the large number of unsourced claims about local food [1]. As the food miles article demonstrates, this is still a very controversy area and it's clearly not as simple as the section seems to suggest. Nil Einne (talk) 17:52, 30 September 2008 (UTC)

Removed an unsupported position about vegan diets

[edit]I removed statements suggesting that it might not be possible for a vegan diet to meet a human's long term nutritional needs. According to the American Dietetic Association, "It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. Well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the lifecycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes."[2] If you're going to make a claim that it might not be possible for a vegan diet to meet nutritional needs in the long term, you're going to need to support that position with references from a reliable source. Red Act (talk) 07:19, 8 July 2009 (UTC)

GHG Data of Steinfeld et al.

[edit]Citing Steinfeld et al. (2006, i.e. "Livestock's Long Shadow"), the article states "Additionally, 37 percent of all anthropogenic methane comes from industrial livestock production, generated by the digestive system of ruminants such as cows, sheep and goats." In fact, this estimate by Steinfeld et al. is for global livestock production, not just industrial livestock production, and it includes methane emitted from manure, not just methane from enteric fermentation. (See Ch. 3 of Steinfeld et al.) Also, citing Steinfeld et al., the article states "it is estimated that livestock production is responsible for 18 percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. This is the second-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, and more than all forms of transportation combined." However, in a peer-reviewed paper, it has been shown that that comparison with transportation proves to be erroneous when both sectors are subject to the same kind of analysis (Pitesky, M. E. et al. 2009. Clearing the air. Adv. Agron. 103: 1-40). One of the co-authors of the 2006 report by Steinfeld et al. has acknowledged the error, as reported in news media, e.g. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/environment/climatechange/7509978/UN-admits-flaw-in-report-on-meat-and-climate-change.html). Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

GHG Data of Goodland and Anhang

[edit]The Wikipedia entry uncritically presents the erroneous percentage of GHGs attributed to livestock by Goodland and Anhang. Goodland and Anhang's figure includes carbon dioxide emission from respiration by livestock. The plant biomass C amount emitted as carbon dioxide and methane from livestock would tend to be emitted as carbon dioxide and methane (but in different proportions) by other herbivores and decomposers metabolizing the biomass in the absence of livestock. In their tally, Goodland and Anhang neglect the reduction of carbon dioxide emission from non-livestock biota that thus occurs due to livestock production. This omission would be unexceptionable if they were tallying gross emissions. However, they do not tally gross emissions, omitting (for example) carbon dioxide emission by respiration from crop plants in their total, and including, as "emissions" attributed to livestock, net photosynthetic offsets foregone due to livestock-raising. They also use a large multiplier for livestock methane and a small multiplier for other methane (for conversion to carbon dioxide equivalents). In summary, they distort methane data and arbitrarily include some source and sink terms while omitting others, to inflate the percentage of emissions that they claim is attributable to livestock. As a result, their emission percentage estimate is meaningless, and uncritically citing this exceptional claim is inappropriate. Note the Wikipedia verifiability precept that "Any exceptional claim requires multiple high-quality sources." Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

GHG Data of Eshel and Martin

[edit]The Wikipedia article uncritically presents an invalid conclusion based on erroneous data and flawed analysis, from the study by Eshel and Martin (2006. Earth Interactions 10, Paper No. 9). Their calculations used figures on fossil fuel energy use in beef, pork, chicken and lamb production, expressed per unit protein energy production, from Table 8.2 of Pimentel and Pimentel (1996. Food, Energy and Society). That table indicates that the data source is Pimentel et al. (1980. Science 207: 843-848). However, in the latter paper, output was expressed on a protein mass basis, and conversion to a protein energy basis by Pimentel and Pimentel (1996) involved calculation error resulting in extremely inflated ratios of fossil energy to meat protein energy in their Table 8.2. The overestimation for beef, pork and chicken is by a factor of about 1.7 if intended to be on a metabolizable energy basis or about 2.2 on a gross energy basis. [Writers of the Wikipedia entry can confirm this by checking the 1996 book and the 1980 paper and consulting Merrill and Watt (USDA Handbook No. 74) for data on metabolizable and gross energy contents of meat protein. The Merrill and Watt publication is a widely accepted source, being approved, for example, by US FDA regulations (CFR 21, sec. 101.9) as a source of energy data for certain food labeling.] The "fossil fuel energy" input figure per unit lamb protein energy production used by Eshel and Martin presents a different issue. This figure vastly overestimates a realistic magnitude and bears no apparent relation to the 1980 data, despite the Pimentels' citation of the latter as the source. In the text of Chapter 8 of Pimentel and Pimentel (1996), this same figure exactly is the feed energy input per unit lamb protein energy output calculated for a range sheep production system. As such, virtually all of it represents photosynthetically captured solar energy. Its inclusion as a fossil energy figure in the Pimentels' Table 8.2 was evidently an error. For all kinds of meat production examined, Eshel and Martin failed to partition alleged livestock production energy input between food and non-food products. Substitutes for the non-food products of livestock would require energy use and involve greenhouse gas emissions, which must be taken into account if estimation of net energy savings and greenhouse gas emission reductions associated with reduced livestock production are to be credible. If one knows how the substitution will be done, the preferred alternative is to do a calculation accounting for the energy used in substitution. If one does not know how the substitution will be done, a credible alternative is using energy partitioning between food and non-food products. With partitioning of energy input among food and non-food products on a product mass basis, Eshel and Martin's energy use figure for beef meat, for example, is found to be inflated by a factor of at least 3.5, relative to the original 1980 data. Analogous partitioning for sheep production energy indicates that their fossil energy input figure assigned to lamb meat is inflated by a factor of approximately 21, relative to a credible figure. The extreme overestimates of fossil fuel energy use assigned to beef, pork, chicken and lamb meat production by Eshel and Martin were used by them in calculating carbon dioxide emissions that they assigned to meat production. There are also other errors and omissions in their analysis, affecting results. The cited GHG results from that paper cannot be presented responsibly without calling attention to important errors that invalidate those results. Note the Wikipedia verifiability precept that "Any exceptional claim requires multiple high-quality sources." Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

US Food System GHGs

[edit]The article states "It is estimated that the U.S. food system is responsible for at least 20 percent of U.S. greenhouse gases." No source that can be checked is cited for this statement.Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Nitrous Oxide Emissions

[edit]The article states "Nitrous oxide (N2O) is 200 times more heat-trapping than carbon dioxide and is emitted as a result of over-tilling and excessive irrigation practices." No source that can be checked is cited for this statement. The phrase "200 times more heat-trapping" is problematic; it would be more accurate to say that nitrous oxide has a 100-year global warming potential estimated at 298 times that of carbon dioxide; a suitable citation for this would be the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report. Moreover, the generalization about causes of nitrous oxide emission is misleading. Nitrous oxide emissions are associated with nitrification and denitrification processes in aerated and anoxic soil environments, respectively; they tend to be increased in response to (a) tilling (not just over-tilling), (b) some irrigation (but not just excessive irrigation), and (c) drainage, which affect these processes acting on mineralized nitrogen in soils, and also in response to (d) application of manure, (e) growing of nitrogen-fixing crops and forages, and (f) decomposition of organic residues, all of which tend to result in increased amounts of ammonium available for nitrification, and in response to (g) application of synthetic nitrogenous fertilizers, which tend to increase the amount of ammonium available for nitrification, or in the case of nitrate fertilizers, supply nitrate that is reduced in the denitrification process. (For a brief summary of the processes involved, see: EPA. 2011. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2009. United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA 430-R-11-005. 459 pp. There are also numerous peer-reviewed papers on these matters.) Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Methane and Global Warming

[edit]Because a large fraction of GHG emissions attributed to food production involves methane (from rice production, ruminal fermentation and manure management), it would be appropriate for the article to comment on interpretation of such emissions in relation to global warming. Like other greenhouse gases, methane contributes to global warming when its atmospheric concentration rises. Although methane from agriculture and other anthropogenic sources has contributed substantially to past warming, it is of much lesser significance for current and recent warming. This is because there has been relatively little increase in atmospheric methane concentration in recent years (Dlugokencky et al. 1998, 2011; IPCC 2007; Rigby et al. 2008). The anomalous increase in methane concentration in 2007, discussed by Rigby et al., has since been attributed principally to anomalous methane flux from natural wetlands, mostly in the tropics, rather than to anthropogenic sources (Bousquet et al. 2011).

- Dlugokencky, E. J. et al. 1998. Continuing decline in the growth rate of the atmospheric methane burden.Nature 393: 447-450.

- IPCC. 2007. Fourth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Rigby, M. et al. 2008. Renewed growth of atmospheric methane. Geophys. Res. Letters, vol. 35, L22805, doi:10.1029/2008GL036037

- Dlugokencky, E. J. et al. 2011. Global atmospheric methane: budget, changes and dangers. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. 369: 2058-2072.

- Bousquet, P. et al. 2011. Source attribution of the changes in atmospheric methane for 2006-2008. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11: 3689-3700.Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Irrigation and Fertilizer Inputs

[edit]The article states "Feed is a significant contributor to emissions from animals raised in Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) or factory farms, as corn or soy beans must be fertilised, irrigated, processed into animal feed, packaged and then transported to the CAFO." Although accurate, this is misleading because the article provides no comparisons with other foods, which may also be subject to fertilizer, irrigation, processing, packaging and transportation inputs. For example, in the US, only about 11 percent of soybean acres and 14 percent of corn acres are irrigated; in contrast, about 66 percent of vegetable acres and 79 percent of orchard acres are irrigated (USDA 2009a,b). For another example, in 1995, commercial fertilizer inputs averaged 11 pounds per acre for US soybean production, versus 157 pounds per acre for US potato production (Anderson and Magleby 1997). It is misleading to imply that soybean crop inputs are wholly assignable to livestock feed derived from those crops. Much of the production and processing input is assignable to soybean oil extracted before the residual material is used as livestock feed. Soybean oil is used for cooking, food products, biodiesel, etc. (Soyatech). Rather than being wasted,the human-inedible hulls are ground and combined with extraction residue in soybean meal used for livestock feed. [USDA (2011) provides soybean and soybean oil production figures, and amounts of soybeans and soybean meal fed to US livestock.]

- USDA. 2009a. 2007 Census of agriculture. United States summary and State Data. Vol. 1. Geographic Area Series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 639 pp. + appendices.

- USDAb. 2009. 2007 Census of agriculture. Farm and ranch irrigation survey (2008). Volume 3. Special Studies. Part 1. AC-07-SS-1. 177 pp. + appendices.)

- Anderson, M. and R. Magleby. 1997. Agricultural resources and environmental indicators, 1996-1997. USDA Ag. Handbook AH712. 356 pp.

- Soyatech: http://soyatech.com/soy_facts.htm

- USDA. 2011. Agricultural Statistics 2010. 505 pp.Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Food Transport

[edit]The article states "Because CAFO production is highly centralised, the transport of animals to slaughter and then to distant retail outlets is a further source of greenhouse gas emissions." Again, the article misleads by failing to present comparative data for other foods. Canning et al. present estimates of US energy use for farm and agribusiness, food processing, packaging, freight services and wholesale and retail for various food categories. Freight services account for only 6 percent of the total energy use associated for beef, 6.2 percent for pork, and 5.6 percent for poultry products, compared with 10 percent of the total for fresh fruits and 12 percent for fresh vegetables, for example. The absolute per capita amount of energy for beef transport is 90 thousand Btu, compared with, for example, 166 thousand Btu for fresh vegetables. Categories involving very large per capita absolute amounts for transport energy include snack, frozen, canned etc. foods, spices and condiments (together totallying 205 thousand Btu) and alcoholic beverages (203 thousand Btu). The exclusive focus on transport relating to GHG for meat derived primarily from intensive livestock production reinforces a reader's impression that the article has cherrypicked content for advocacy purposes. (The reference cited here is Canning, P., A. Charles, S. Huang, K. R. Polenske, and A Waters. 2010. Energy use in the U. S. food system. USDA Economic Research Service, ERR-94. 33 pp.)Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Digestibility of Grass

[edit]Comparing CAFO beef with grassfed beef, the article refers to "higher digestibility of grass by cattle", citing some Worldwatch paper. The statement is erroneous. National Research Council (2000. Nutrient requirements of beef cattle. National Academy Press. 232 pp.) tables indicate TDN of pasture grass ranging from 74 % (spring) to 53% of DM (fall), and TDN of grass hays mostly in the range of 55 to 60 % of DM, whereas corn grain and soybean meal have TDN of about 88 % and 84 % of DM, respectively. Because feedlot diets commonly include grain, and may also include soy meal, in addition to forages, digestibility tends to be lower for grass than for feedlot rations. Numerous other credible sources are in good agreement with NRC (2000) on this matter. Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

Food Production Emissions

[edit]The article states "When looking at total greenhouse gases (not just carbon dioxide), 83% of emissions come from the actual production of the food because of the methane released by livestock and the nitrous oxide due to fertilizer." It is not clear what the figure is supposed to represent. If it means 83 percent of emissions assignable to the US food system, the figure does not agree with estimates based on USDA and US EPA data. In that case, the Wikipedia statement would appear to be an exceptional claim, for which a single source is inadequate. Note the Wikipedia verifiability precept that "Any exceptional claim requires multiple high-quality sources." Also, even if one focuses just on emissions associated with agricultural production, the Wikipedia statement is misleading because it ignores the considerable contributions from sources other than livestock and fertilizer. For example, EPA (2011) indicates that for the US, only 39.3 percent of agricultural anthropogenic nitrous oxide emission is assigned to fertilizer (including manure) sources; about 71 percent of agricultural methane emission is released from livestock.Schafhirt (talk) 21:14, 7 March 2012 (UTC)

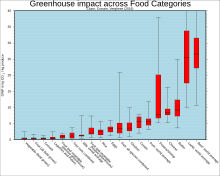

Clune et al. 2016

[edit]

How about adding the meta-analysis of Clune et al. (2016)? Stephen Clune, Enda Crossin, Karli Verghese: Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. In: Journal of Cleaner Production. 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.082 --DeWikiMan (talk) 18:24, 11 October 2016 (UTC)

External links modified

[edit]Hello fellow Wikipedians,

I have just modified one external link on Low-carbon diet. Please take a moment to review my edit. If you have any questions, or need the bot to ignore the links, or the page altogether, please visit this simple FaQ for additional information. I made the following changes:

- Added tag to https://grabnete.com/produkt/venduzi-komplekt/

- Added archive https://web.archive.org/web/20090113175530/http://www.lowcarbondiet.ca/low_carbon_diet_options.html to http://www.lowcarbondiet.ca/low_carbon_diet_options.html

When you have finished reviewing my changes, you may follow the instructions on the template below to fix any issues with the URLs.

This message was posted before February 2018. After February 2018, "External links modified" talk page sections are no longer generated or monitored by InternetArchiveBot. No special action is required regarding these talk page notices, other than regular verification using the archive tool instructions below. Editors have permission to delete these "External links modified" talk page sections if they want to de-clutter talk pages, but see the RfC before doing mass systematic removals. This message is updated dynamically through the template {{source check}} (last update: 5 June 2024).

- If you have discovered URLs which were erroneously considered dead by the bot, you can report them with this tool.

- If you found an error with any archives or the URLs themselves, you can fix them with this tool.

Cheers.—InternetArchiveBot (Report bug) 14:01, 7 January 2018 (UTC)

Wiki Education assignment: Conservation Biology

[edit]![]() This article was the subject of a Wiki Education Foundation-supported course assignment, between 21 August 2023 and 1 December 2023. Further details are available on the course page. Student editor(s): Sharko2002 (article contribs). Peer reviewers: TheDenverGoose.

This article was the subject of a Wiki Education Foundation-supported course assignment, between 21 August 2023 and 1 December 2023. Further details are available on the course page. Student editor(s): Sharko2002 (article contribs). Peer reviewers: TheDenverGoose.

— Assignment last updated by Otter246 (talk) 22:12, 16 October 2023 (UTC)

Is this article neutral?

[edit]@95.235.54.191: What criticism did you want to add? Chidgk1 (talk) 17:02, 29 October 2023 (UTC)

- Start-Class Environment articles

- Low-importance Environment articles

- Start-Class Climate change articles

- High-importance Climate change articles

- WikiProject Climate change articles

- Start-Class Food and drink articles

- Low-importance Food and drink articles

- WikiProject Food and drink articles

- Start-Class Veganism and Vegetarianism articles

- Low-importance Veganism and Vegetarianism articles

- WikiProject Veganism and Vegetarianism articles