Talk:Accidental (music)/Archive 1

| This is an archive of past discussions about Accidental (music). Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

| Archive 1 |

Page move

It was suggested that this article should be renamed Accidental. The vote is shown below:

- Support Accidental (biology) is a redirect to a completely different term. No way is that as common a usage as the musical one. —Wahoofive (talk) 20:01, 15 August 2005 (UTC)

- Do not support Accidental (biology) is a redirect to an article which discusses the subject of accidentals in biology; however, because there is more than one term for the concept, a somewhat arbitrary choice had to be made for the title (or else two separate but identical articles would have had to be written). The substantive point here is that the article covers the subject, and follows Wikipedia convention in showing the synonymous redirecting term in bold in the first paragraph. As to which is the more common usage, I feel some evidence would help inform the discussion. - SP-KP 22:40, 16 August 2005 (UTC)

It was requested that this article be renamed but there was no consensus for it be moved. violet/riga (t) 14:06, 21 August 2005 (UTC)

Rewrite

My rewrite still requires some work on the Turkish system, which I know nothing about, and the derivation of the symbols from medieval times.

I removed the following because it didn't seem to fit the topic, and in any case is simplified to the point of uselessness:

- The rules for which accidentals to choose may vary according to the type of music: modal, diatonic or chromatic, and also whether the transcriber is aiming for strictness or clarity, for example C flat versus B in the key of D flat. Nonetheless, some general rules for choosing between flat or sharp accidentals include:

- When descending, use flats.

- When ascending, use sharps.

- Try to use the same kind of accidentals -- sharps or flats -- used by the key signature.

I also removed the following due to dubious accuracy; my experience is that C# is higher than Db:

- On a piano or other equally tempered instruments with fixed tuning, a sharp and a flat are the same distance from the natural note in either direction (so that C sharp is the same as D flat - they are enharmonically equivalent), while instruments with flexible tuning such as violins or cellos are often played so they more closely approximate just intonation, meaning sharps tend to be lower and flats higher (so that C sharp is slightly lower than D flat).

- The first part of this statement (about instruments with fixed tuning) is certainly correct. If there's disagreement about the second part, couldn't the statement be revised simply to say that C# and Db (for example) may not be the same? Dsreyn 14:19, 3 November 2005 (UTC)

I also removed this because I couldn't figure out what it means (perhaps could be summarized in a few sentences about inconsistent use of symbols):

- In some of the autographs of the 17th and 18th one does not notice the incoherence of the modern accidental notation, in which the value of the altered note does not depend on the key signature contrary to the value of the unaltered note, which, among other things, makes sight transposition more awkward that it ought to be.

- In such scores (e.g. autographs by J.S. Bach) the value of the altered note does in fact (as it ought to) depend on the key signature. For example a flat sign before B means Bb in the key of C major but Bbb (B double-flat) in the key of F major. Similarly a sharp sign before A means Ab in the key of C major but A natural in the key of Eb major. A natural sign before B means B natural in the key of C major but Bb in the key of F major and it needs to be used only if the B had been previously flattened or sharpened. (Generally speaking the natural is always used to restore the value of the note to that of the key signature, never to cancel an accidental in the key signature.)

- Not only does this manner of notating accidentals avoid the awkwardness in sight transposition alluded to above, but it also almost never requires the use of double-flats and double-sharps. Also the natural sign is always used to restore the value of the note to that of the key signature, never to cancel an accidental in the key signature.

- Modern editions of course always change this style of marking accidentals to the modern style (in the case of full scores, not necessarily in the case of a figured bass, see below) even if the original score is notated in the old manner. But this style can still be seen in some editions for the notation of figured bass chords even today (or at least quite recently, long after this style of notation had been abandoned for scores.)

Finally, I removed this from the hexachord discussion:

- (It might also have helped that H was the letter which followed G so that it completed the alphabetic series A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, but that is not the reason Germans use H for B natural, it is at best an a posteriori justification; rather the real origin is that stated above, namely a deformation of a square B) — Preceding unsigned comment added by Wahoofive (talk • contribs) 06:29, 13 March 2005 (UTC)

how many steps ?

I'm sorry but I seriously do not understand the sentence quoted below. Are you simply trying to say that G# is two semitones away from Gb ? Or are you inferring that a Gb becomes an F if there happens to be a G# in the same measure. I'm no expert but I do know a little bit about writing music -- and that does not sound right.

Thanks,

Note that in a few cases the accidental might change the note by more than a semitone: for example, if a G sharp is followed in the same measure by a G flat, the flat sign on the latter note means it will be two semitones lower than if no accidental were present. Thus, the effect of the accidental has to be understood in relation to the "natural" meaning of the note's staff position.

- I agree that passage is unclear. What it intends to say is that although a flat sign normally lowers the note by a half step (from what the note would be without the accidental), if the prevailing accidental (whether from the key signature or a preceding accidental) is a sharp, the effect of the flat is to lower it two semitones: from the sharp to the natural, then to the flat. In fact, if there was a previous double-flat on the same note in that measure, the effect of the flat might be to raise the note, cancelling the double flat. I'm not entirely certain this information needs to be included at all, but that's what it's supposed to say. Editors are encouraged to edit it for clarity. —Wahoofive (talk) 04:35, 11 November 2005 (UTC)

Which way must an accidental go?

What is the rule governing the "direction" an accidental is notated?

For example, in the Bach piece shown in Musical notation, the first accidental (third measure) is a sharpened F. Could this be notated as a flattened G instead? And if not, why not? -- Paul Richter 07:26, 31 May 2006 (UTC)

- The accidentals are mostly governed by the key, and the function of the altered note. By writing an F# it is clear that a parallel sixth is used. (G-B -> F#-A). Zanaq 09:50, 31 May 2006 (UTC)

- Also see diatonic function, enharmonic. —Wahoofive (talk) 06:08, 11 August 2006 (UTC)

Chapter Suggestion

Should there be something on the different ways to annotate? For instance, unicode, <alt> combinations in Windoze, any special key combinations to the Mac, etc.... I remember reading somewhere on Wikipedia that there is a stylistic guidline for how to annotate, and one way is recommended above all others, but I forgot where I read it...

Just a humble suggestion.... NDCompuGeek 06:58, 23 January 2007 (UTC)

- I'd say no. I think, by the way, "annotate" is not the word you're looking for. Anyway, sharp and flat signs are just particular instances of special characters, and "how to do special characters on your computer" is not really within the scope of an article on music. As for stylistic guidelines for Wikipedia, see Wikipedia:Manual of Style (music). -- Rsholmes 11:51, 23 January 2007 (UTC)

Microtonal section - Sagittal accidentals

I would like to add something like the following to the end of the Mirotonal section, but I have a conflict of interest: The Sagittal notation system is a comprehensive system of mirotonal accidentals and the rules for applying them. It is capable of notating microtonal music in almost any tuning. It was developed by collaboration on the Yahoo groups "tuning" and "tuning-math" beginning in January 2002. D.keenan 00:48, 8 December 2006 (UTC)

- Done. And I have no conflict of interest. I not even sure I like Sagittal all that much... though I'm hardly qualified to pass judgement... Oh, and here Secor says he started developing Sagittal in August 2001, so that's the date I quoted. -- Rsholmes 04:04, 8 December 2006 (UTC)

On 27 March 2007 someone identified only as 76.81.164.27 deleted the mention of the Sagittal notation system, describing it as a "non-notable discussion of a nonstandard notational system". There is as yet, no standard microtonal notation system. But Sagittal seems to me to be no less standard and no less notable than Ben Johnston's notation for JI, whose mention was not deleted. D.keenan 01:20, 2 April 2007 (UTC)

black keys of the Musical keyboard

The article Marimba refers to the non natural notes on the instrument as Accidentals. I found in Musical keyboard the same usage where the black keys are called Accidentals. This article doesn't mention this usage. It could be useful to add a paragraph mentioning it.-Crunchy Numbers 20:23, 1 November 2006 (UTC)

- Here are a few definitions and usage examples from http://books.google.com:

- "sharp ... (d) on a piano keyboard, one of the black keys ..." Musical Dictionary By W L Hubbard (1908 repr. 2006)

- "The ebonies are the black KEYS of a piano, called variously sharps or accidentals,..."

- "The ivories are the white KEYS of the piano (also called naturals), ..."

- Piano: An Encyclopedia By Robert Palmieri, Margaret W. Palmieri (2003)

- "The basic arrangement of naturals and interspersed, raised accidentals (the modern piano's white and black keys) was standardized long before 1700 ..." Eighteenth-Century Keyboard Music By Robert Lewis Marshall (ed.) (2003)

- "It is quite common for the natural keys to be black and the accidentals white, the reverse colouring to the modern piano; ..." Musical Instruments By Murray Campbell, Clive A. Greated, Arnold Myers (2004)

- "In order to indicate when the black keys on the keyboard are to be played, symbols called accidentals are used." p. 174

- "The black keys were not originally felt to be an entirely legitimate part of the scale, the way the white keys were. They were sort of harmonic accidents." p. 15

- A Player's Guide to Chords & Harmony By Jim Aikin (2004)

- --Jtir (talk) 14:19, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

Inflections vs accidentals

- Further discussion: Talk:Circle of fifths#Introduction: Accidental sign

The symbols sharp, flat, natural etc are not called accidentals. "Accidentals" refers only to the use of such symbols to depart from the key signature. I've consulted 4 dictionaries of music, which give no generic term for them. The closest is The Oxford Companion to Music, which has a table of "Names of Inflections of Notes" at the front, but in the actual entry for "sharp" etc just calls it a symbol.

If we want to cover sharps, flats & naturals on one page, I suggest the name "Note inflection symbols", but we would need to specify that such a term is merely a Wikipedia invention for convenience. -- Tarquin

Harvard Dictionary of Music begins its entry for Accidental with

- The signs used in musical notation to indicate chromatic alterations or to cancel them.

So this definitely agrees that the symbols themselves are accidentals. Wahoofive 00:25, 12 Mar 2005 (UTC)

- Nope, not at all definitely. "Chromatic alteration" from what? From the existing sharps or flats in the key signature, which typically indicates a diatonic mode. In D major, neither a C sharp nor an F sharp is an accidental; they're just there, part of the tonal environment. Canceling one of those with a natural sign makes an accidental, a chromatic alteration from the diatonic major scale, same as flatting a B or sharping a G there would do. __Just plain Bill (talk) 03:00, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

- Since "inflection" means change in pitch, the same rhetorical question arises, "change from what?" If accidental is inappropriate because it implies a change, what makes inflection different? Hyacinth (talk) 04:38, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

"Key signature: An arrangement of accidentals at the beginning of a staff..." Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.361. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0. (Note, however, that the book avoids describing accidentals or key signatures in this manner within the body of the text) While it may not be literally and/or technically correct it appears to be fairly common usage to describe the flats and sharps in key signatures as accidentals. Hyacinth (talk) 04:38, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks for this quote. It appears to support a fourth sense of the term accidental:

- "a note foreign to a key indicated by a signature"

(Is a natural an accidental or not?) - "a prefixed sign indicating an accidental"

an accidental sign in the key signature (Benward & Saker) (This sense does not include the natural sign, IIUC.)- the black keys on a musical keyboard (Palmieri & Palmieri)

- "a note foreign to a key indicated by a signature"

- See also accidental.

- --Jtir (talk) 20:52, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

- and if you follow the musical Britannica link in that dictionary dot com "reference" (yes, I'm being snarky about that one, which is otherwise something I take pains to avoid online in general, and on wikipedia pretty rigorously) you will find it says

something like "these signs when found in a key signature are not considered accidentals."__Just plain Bill (talk) 00:24, 2 August 2008 (UTC) - Here's the quote, pasted from Britannica:

- and if you follow the musical Britannica link in that dictionary dot com "reference" (yes, I'm being snarky about that one, which is otherwise something I take pains to avoid online in general, and on wikipedia pretty rigorously) you will find it says

"Sharps or flats that are placed at the beginning of a musical staff, called a key signature, indicate the tonality, or key, of the music and are not considered accidentals."

- The definitions concerning key signatures appear to refer only to "standard" key signatures. Hyacinth (talk) 21:23, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

- It's common engraving practise to put natural signs into the signature that changes key in mid-piece, either in the middle of a staff or system, or at the end of the staff/system just before the change. IIRC, going from G to C would have a natural on the F line; D major to minor would have two naturals and a flat.

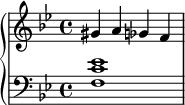

Going on sketchy memoryhere you see an example going from D to G in the middle of a line. - Also guessing when I say that tunes in sharp+flat key sigs (e.g. in Klezmer music, the D Freygish scale, which is written with two flats and a sharp) may have accidentals as well, that follow similar rules as diatonic notation does. __Just plain Bill (talk) 22:43, 1 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks for providing this example. It would make a useful addition to this article and to key signature. I am striking myself above and believe that what Benward & Saker are saying could be interpreted by disambiguating the term "accidental":

- "Key signature: An arrangement of accidental

s[signs] at the beginning of a staff..."

- "Key signature: An arrangement of accidental

- Does their def encompass a key signature after a double bar in the middle of a staff? Or is their def, as Hyancith suggests, a kind of key sig that is "standard". With this interpretation, B&S could be defining a restricted sense of the term (perhaps to keep it simple?).

- Not sure how to interpret EB, since their contributors are usually subject specialists, IIRC.

- As editors we need to identify the different senses of the term, just as lexicographers do, even though dictionaries and other reference works are supposed to have already done that. :-)

- --Jtir (talk) 18:34, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- I looked at EB's article on "key signature" — they explicitly mention the double bar, yet restrict to sharps and flats. Unfortunately, they make it difficult to copy quotes. --Jtir (talk) 18:44, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- Encyclopedia Britannica probably still deserves the high place it has on my reliability index, although this is the first time I've peeked at the online version. To me an encyclopedia is still eight to ten feet of shelf space taken up with thick quarto volumes, although my view of that is beginning to change.

- In the image above, that C natural before the double bar is most definitely an accidental. I wouldn't hesitate to call the cluster of a natural and a sharp after that double bar a "key signature" and I wouldn't hesitate to call anyone who disagrees "wrong."

- In a considerately engraved part, that double bar and its following natural/sharp key signature would come at the end of a line anyway, with the following staves showing a regular G signature. Sometimes ease of sight-reading takes second place to cramming as much on a page as possible. __Just plain Bill (talk) 19:32, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- "that C natural before the double bar" — Thanks for pointing out this example. M-W's dic def doesn't seem to quite capture this case. TAHD implicitly mentions the natural sign. (It's 3rd from the top and never uses the words sharp, flat, or natural.)

- Another source re natural signs in key sigs:

- "The only complicated key change is when you're changing to the key of C — which has no sharps or flats. You indicate this by using natural signs to cancel out the previous sharps or flats, like this:"

- --Jtir (talk) 20:18, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks for providing this example. It would make a useful addition to this article and to key signature. I am striking myself above and believe that what Benward & Saker are saying could be interpreted by disambiguating the term "accidental":

- It's common engraving practise to put natural signs into the signature that changes key in mid-piece, either in the middle of a staff or system, or at the end of the staff/system just before the change. IIRC, going from G to C would have a natural on the F line; D major to minor would have two naturals and a flat.

That brings up the issue of context. Note, for example, that the Britannica quote says, "considered accidentals". By who and in what context is Britannica discussing? Musical practice? Musical theory? Their own consideration? It sounds like sharp and flat signs may or may not be considered accidentals depending on where they appear, in the world of precise music theory and analysis, but that they are often called accidentals no matter where they appear, in the world of musical practice and associated theory. The issue of practice leads use to the question of purpose.

What is the use of distinguishing between the signs when they appear in key signatures, and in which case it is argued we have no word for them, and when they appear as "accidentals"? Hyacinth (talk) 19:53, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- That C natural is the accidental there, and the natural sign that marks it is not; it's just a natural sign. Is that a reactionary view? Didn't the signs themselves start out as neumes marking accidental notes, afterwards being used in key signatures? (Just saying; don't know.)

- Or, shall we co-opt a word with a pre-existing meaning, and make it serve for a collective term we don't have, but feel a need for? Why do we need a special word for the category comprising sharps, flats, and naturals anyway? "Nice to have for technical discussions" or "making the taxonomy of musical signs hierarchically regular" do not count as "needs" in my opinion.

- The simple fact I see here is that the great bulk of this signage occurs in "standard" diatonic music. In D minor, a B flat is not an accidental. In D major it would be. Anyway, my mission here is not to split musicological hairs, but to present something understandable by the intended audience; here I believe that to be folks who are interested in the basics of standard diatonic notation, and may find pointers to more esoteric topics more useful than in-line treatises on stuff that is way over their head. __Just plain Bill (talk) 20:25, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- To answer your question more directly, I believe it is useful to that audience to make a difference between the tonal environment, mostly in a diatonic context but not necessarily in fixed-do C major, and the oddities that are exceptional in that environment, or accidentals. __Just plain Bill (talk) 20:32, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- This seems to be the EB source for Bill's quote. A different EB def of "key signature" doesn't use the word "accidental". (Not sure why they differ — different editions?)

- I feel the phrase "Sources vary ..." is in our future. :-) --Jtir (talk) 20:41, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

"Accidentals. This comprehensive term is employed, for want of a better, to denote all sharps, flats, and naturals used apart from those in the key-signature." from "Musical Notation. Practical Ways of Expressing Details of Musical Composition. Section V. Accidentals (Continued)." H. Elliot Button. The Musical Times, Vol. 55, No. 861 (Nov. 1, 1914), pp. 652-653. Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Hyacinth (talk) 20:58, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

Does raise/lower suffice?

I'm about to edit the lead, and lose "inflect," which connotes the kind of thing that might happen in scat singing, or vocalese, or Non-lexical vocables in music. I'm thinking of pitch-bending ornaments applied to a "single" note, such as:

- DESCENDING GLISSANDO, keep the real note for a while, then start with glissando and crescendo, enjoying chromatism.

- DOIT, a sort of long and big glissando pushed to the highest -non fixed- pitch you can.

- PLOP, similar to a ghost grace-note (often with a sound like "dwi"). It is performed by a quick downward slide to a given note from a large interval above.

- FLIP, a quick upward lift followed immediately by a rapid drop to the next note.

- DIP, between two notes: after tuning the first one, slide downwards and then go up again -like a glissando- to the second one (like with an olive in Martini!)

- SHAKE, a big tremolo between the written note and a higher pitch, at least a major second. It often includes a crescendo and an accelerando.

Found that here.

When I get time to fix all the incoming links, I intend to change the heading "Inflections vs accidentals" to "Accidentals & key signatures" or some such, since that's the way that discussion seems to have gone. __Just plain Bill (talk) 21:30, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- I do not see how raise and lower are any more specific. Hyacinth (talk) 21:45, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- Could you say more about that, please? The article says "symbol used to raise or lower the pitch of a note ..."

- Now I'm going to add something about semitones to the lead. __Just plain Bill (talk) 22:18, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- I don't see how your quote above supports the idea that inflection implies those techniques. I don't see how "raise" or "lower" implied not using those techniques. Hyacinth (talk) 23:57, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

- Quote wasn't meant to support, but illustrate. Wiktionary calls inflection a change in tone of voice, among other things. It also mentions curvature and turning. Could one call the tones used in e.g. Chinese and Vietnamese inflections? Some of those tones have a straight pitch contour, some are curved or even S-shaped.

- Together with the nearby pitch and semitone links, "raise/lower" simply implies straight unbent, unvaried pitch. Ornamentation is another story, not forbidden, but not implied either. __Just plain Bill (talk) 00:39, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- Would accidental signs ever be used to denote pitch changes of less than a semitone or ornamental changes like those listed above as inflections? --Jtir (talk) 00:23, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- "by a number of semitones": that's perfect — I never would have thought of that. --Jtir (talk) 00:28, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- I don't see how your quote above supports the idea that inflection implies those techniques. I don't see how "raise" or "lower" implied not using those techniques. Hyacinth (talk) 23:57, 2 August 2008 (UTC)

comments on the lead

- As a reader of the lead, I would like to know why they are called "accidentals" (What accident?) and which changes (in pitch) are "accidental" and which changes are not (inflections?). (Likewise for the article body.)

- Some dictionaries distinguish an "accidental note" from an "accidental sign". The former is what is heard, the latter is what is written. The lead conflates the two.

- IMO, this article could use a lead longer than one sentence:

- "The lead should be able to stand alone as a concise overview of the article."

- The lead does not explicitly name any of the accidental signs.

- The lead makes no mention of notations for non-Western and microtonal tuning.

- The lead gives no indication that the use and interpretation of accidental signs in notated music is subject to complex rules and that sometimes courtesy accidentals are provided where the rules do not require them. (Who makes these rules? How are they formally documented? Why are courtesy accidentals needed at all?)

- The lead makes no mention of the history of the notation, which can be traced back to Gregorian chant in which only the note B could be altered, or that modern accidental signs are variations of the letter B.

- "Black keys" are not mentioned anywhere else in the article, so the second sentence does not count as a summary. It does suggest a way to expand the article. There are several sources listed above that document this use of the term "accidental", some giving interesting and enlightening historical context.

--Jtir (talk) 17:36, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks for standing back and looking at a bigger picture. I confess I hadn't noticed how short the lead was. I knocked together a sandbox draft which seemed OK to me, so I went ahead with it into the article. It doesn't mention the history, and I'm OK whether it does or not. Carry on, guys, hammer away... __Just plain Bill (talk) 20:50, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks! Nice work. That is way beyond anything I could hope to do. I like the way you phrased this: "most recently applied key signature".

- Do you want to standardize on "sign" or "symbol"? Note uses "sign" in the lead and "symbol" elsewhere.

- I'm still wondering how accidentals are related to inflections or Musica ficta (if at all — there doesn't seem to be an article on musical inflections. Is that a non-standard or rarely used term? I saw the interesting list of inflection names, BTW).

- --Jtir (talk) 21:31, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- I'm content to use "sign" and "symbol" interchangeably here; keeps the text from getting dull, IMO. There may be specialists who distinguish the two words nicely, but an exploration of that would most likely TLDR in my view.

- As I understand them, ficta are an early form of accidental, sometimes notated, but mostly applied by the performer based on rules that are now difficult to reconstruct, and were probably inconsistent even in the period of their use. __Just plain Bill (talk) 21:52, 3 August 2008 (UTC)

- One thing I'm worried about is duplication of content/redundancy. A some of the information recently added to the lead is repeated in the next section.--Dbolton (talk) 04:53, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- WP:LEAD says: "The lead should be able to stand alone as a concise overview of the article.", which may be interpreted as saying that, for some readers, the full article is TLDR. --Jtir (talk) 13:23, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- "... the lead will usually repeat information also in the body, ...". (WP:LEADCITE)

- There are some specific guidelines for the length of the lead here.

- --Jtir (talk) 22:03, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- Now that the history bit (Gregorian chant, the letter "B") is where it is, it's not so immediately repetitive. I can live with that. __Just plain Bill (talk) 22:48, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks for your additional improvements. That makes a very respectable lead.

- I also like your explanation of courtesy accidentals. Later the article says that: "Publishers of jazz music and some atonal music sometimes eschew all courtesy accidentals." Is that notable?

- If you can figure out a way to improve the history sentences (maybe combine into one), feel free. I like to read a little history and these explain the gist, but they don't quite cohere.

- Dbolton, thanks for rearranging the lead. The word "canceled" is spelled inconsistently though. Which way do editors want to spell it in this article?

- BTW, the problem I see with redundancy is maintaining consistency between the lead and the article.

- --Jtir (talk) 23:24, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- Inconsistent spelling doesn't bother me. I generally smite ignorant spelling with alacrity, but not with malice nor thinking less of the orthographically challenged, just with dispatch. Other fires to stomp out first.

- Jazz/atonal eschewing of courtesy accidentals seems credible, in the spirit of "Play the music, not the chart, kid -- I ain't here to hold your hand, got my own problems."

- If it's a consistent variation of editing style between genres, it's worth keeping mention of, IMO, subject as always to the need for citing somebody credible and reliable.__Just plain Bill (talk) 00:52, 5 August 2008 (UTC)

- Sorry for changing the spelling. Ignorance on my part. --Dbolton (talk) 03:02, 5 August 2008 (UTC)

- Count me among the ignorant ones, then. I'm still trying to come to terms with "logical punctuation." It made sense when I was ten, but years of schooling drilled it out of me. Now it's OK, and my little world crumbles. Shattered pieces picked up, boss, movin on with my life, boss. __Just plain Bill (talk) 03:24, 5 August 2008 (UTC)

- Now that the history bit (Gregorian chant, the letter "B") is where it is, it's not so immediately repetitive. I can live with that. __Just plain Bill (talk) 22:48, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

- WP:LEAD says: "The lead should be able to stand alone as a concise overview of the article.", which may be interpreted as saying that, for some readers, the full article is TLDR. --Jtir (talk) 13:23, 4 August 2008 (UTC)

Note-by-note accidentals

In the section discussing the alternative system for note-by-note accidentals (in which accidentals last for one note as opposed to an entire bar) the first "rule" read as follows:

"Accidentals affect only those notes which they immediately precede, and those notes that are within the same measure."

This is a contradiction...how can an accidental affect ONLY the note it precedes AND the notes within the same measure? I changed it to this:

"Accidentals affect only those notes which they immediately precede"

Which is much clearer. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 74.137.102.30 (talk) 06:48, 23 August 2008 (UTC)

- I just tried to reword it for better clarity--Dbolton (talk) 05:05, 24 August 2008 (UTC)

- That section cites Kurt Stone's Music Notation in the Twentieth Century as a source. Maybe it would be better to simply quote him directly. (Assuming he provides a similarly concise list of rules — I haven't seen his book.) --Jtir (talk) 21:04, 25 August 2008 (UTC)

Accidental (music) "Collectively, the symbols used to mark such notes are called accidentals."

Excellent article!

A slight modification to the following sentence might be helpful.

In musical notation, the symbols used to mark such notes, sharps (♯), flats (♭), and naturals (♮), may also be called accidentals.

Would changing it to one of the following improve it a bit?

"Collectively, the symbols used to mark such notes are called accidentals."

or

"As a group, the symbols used to mark such notes are called accidentals."

71.232.143.181 (talk) 15:21, 30 October 2008 (UTC)Paul

Accidentals with Ornaments

One question to which I've not been able to find an answer (And I believe would belong on this page) regards the use of accidentals with ornaments (acciaccatura, appogiatura, etc). It seems to me in common notation that an accidental applied to an acciaccatura does not affect the following notes in the same measure.

If anyone can find an incorporate that information that'd be excellent.

Leemute (talk) 20:54, 24 December 2008 (UTC)

Sharp sign origin

The text on the bottom of this article tells the origin of the flat and natural signs, but does anyone have info on the origin of the sharp sign?? Georgia guy 22:54, 4 February 2006 (UTC)

- The sharp is a variant of the natural sign, originally used to raise the Bb to B -- the two signs were used interchangeably in the 15th-16th centuries, and the natural sign was sometimes used to indicate F#. The flat sign was sometimes used to cancel a sharp -- even as late as Bach. A sign resembling our modern double-sharp was also used to indicate sharp. (Source: Harvard dictionary of music) —Wahoofive (talk) 06:08, 11 August 2006 (UTC)

- A little more information about the predecessor of our "modern Western music" sharp sign: it is classified in The Unicode Standard (Musical Symbols section, range $1D100–$1D1FF) as a "croix" with the character code of $1D1CF. - NDCompuGeek (talk) 03:37, 2 December 2009 (UTC)

Additional citations

Why, what, where, and how does this article need additional citations for verification? Hyacinth (talk) 22:05, 2 August 2010 (UTC)

- And now apparently it doesn't. Hyacinth (talk) 03:55, 9 March 2011 (UTC)

Octave

If a lot of people say that an accidental affects notes in octaves other than the one it was originally placed upon then we should be able to get a citation for that claim. Hyacinth (talk) 06:36, 3 April 2011 (UTC)

- That text is gone for now, and may be restored along with with a citation of a reliable source. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 12:52, 3 April 2011 (UTC)

Viewing Problems

I seem to be having trouble on my computer viewing the symbols for the flat symbol, which is quickly replacing the lowercase b in usage. Could anyone direct me to where I can download a patch or program that will allow me to see them? Oh, and by the way, I'm running Windows XP and viewing with Internet Explorer v.6.0.2900.2180.wpsp_sp2_gdr.050303-1519IS. Thanks in advance! MToolen 03:26, 7 January 2006 (UTC)

- I think this is a problem with Internet Explorer. Other browsers, such as Firefox, Opera, and others, display these characters correctly. Any word on whether this works with current beta versions of IE 7? --Dbolton 02:51, 11 August 2006 (UTC)

- I downloaded IE 7 to answer my own question. This bug has not been fixed as of beta 3. Do Mac users have this problem too? --Dbolton 16:45, 11 August 2006 (UTC)

We created Template:Music to address this viewing problem that affects a significant number of users. For example {{music|sharp}} produces ♯ which should display correctly even in Internet Explorer.--Dbolton 21:38, 10 July 2007 (UTC)

- In the introductory section, I don't see any symbols for microtones in the quoted passage -- just empty parentheses. If this is intentional, it's confusing, and should be explained. If it's not intentional, it should be fixed.

- Also, the illustration of the basic accidentals appears to be either black or very dark gray on a black or very dark blue background. The symbols are therefore virtually invisible -- it lookes like a black rectangle inside a white border. I have occasionally encountered this in other Wiki articles, and even fixed it a few times, when a properly colored alternate image was available. But I'd suggest that this phenomenon needs to be examined and corrected in a broader way, across all articles which are afflicted with it. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 74.95.43.249 (talk) 19:32, 23 April 2013 (UTC)

- Hmm. I reverted your change to GIF before reading this. Are you viewing the page on a mobile gizmo? The SVG renders as black on white here in FireFox. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 19:51, 23 April 2013 (UTC)

After clef changes

Do accidentals still hold after a clef change (provided it's still the same bar)? (Courtesy accidentals are very often used in such scenarios, thus making the actual rule hard to guess.) (My personal opinion is yes, but can see reasons for no.) What's the history of this? Double sharp (talk) 12:39, 21 May 2013 (UTC)

- Sounds like a good topic for a dissertation. You'd probably have to search through thousands of scores to find a single example. —Wahoofive (talk) 15:32, 21 May 2013 (UTC)

- Think I found one here: the first edition of Alkan's Op.15 études/caprices. Here it seems to be assumed that they still hold.

- The third piece of the set is probably a record for one of the earliest instances of tuplets crossing the barline! Double sharp (talk) 11:44, 22 May 2013 (UTC)

- The near-universal usage of courtesy accidentals in such situations is all very well if your aim is to read through the score without confusion, but it makes it very hard to find out what the rule actually is. This edition doesn't include any, but (1) the harmonic rhythm is slow when it occurs, so the intention is obvious, (2) there are cases of missing accidentals in other parts of the score (although this is carried out consistently), and (3) the notation is not completely standard (the editor seems to have an allergy towards tuplet numbers, which makes things very confusing!) Double sharp (talk) 11:48, 22 May 2013 (UTC)

- I think you're making a mistake in assuming there is such as "rule". Music engravers (and composers writing manuscript) notated music for centuries before anyone felt the need to codify the practice with a rulebook, and even then what they did was document the prevailing practices, in some cases proclaiming one usage right and another wrong even though both were in use. Music notation "rules" didn't exist a priori, and it's not that hard to find exceptions to many of the pronouncements of music theory books. For a rare situation like the one you're asking about, it may be that publishers have been quite inconsistent in their practice over the centuries. Anyway, due to WP:NOR, this article should probably focus on what music notation books have said. —Wahoofive (talk) 14:43, 22 May 2013 (UTC)

- True, there may not be a real codified rule (though there surely must be one somewhere in some music publisher's guidelines), yet there is a set of conventions which performers will assume. Such things can be inconsistent: the example above has slow harmonic rhythm, so the performer will assume the harmony has not changed. In fact, the performer's actual reading may be different from the codified rules: for instance, if a performer was confronted with this:

- I doubt he would play all notes as A-sharps except the third. He would probably play A-sharps throughout, as (1) it is very likely a typo (if it were to occur in a printed score) and (2) if A-natural were truly intended, no composer or publisher with any respect for the performer would fail to provide a courtesy accidental. This is of course contrary to the "official" codified rule. (Some early editions, e.g. the one on IMSLP of Alkan's Op.39 No.4 étude, are remarkably stingy with courtesy accidentals, not even marking the E-flat in the last bar, despite there being an E-natural in the same octave in the immediately previous bar! I suppose this would be a case of assuming the performer would reason the other way around: that if E-natural were truly intended, the accidental would have been repeated...)

- While this usage of courtesy accidentals is all well and good for the performer, it becomes harder to track down what the codified rules would be in odd situations. In addition, publishers (probably in the past though like this one from 1837) might plausibly assume that performers would be able to musically deduce what must be the correct reading. Yet, such logic can go both ways (as shown above)! Double sharp (talk) 14:19, 23 May 2013 (UTC)

- Adding to the difficulty of tracking things down is the occasionally notorious poor standard of proofreading in music engraving. Here is an Elizabethan example:

- Father - Roland, shall we have a song?

- Roland - Yea, sir. Where be your books of music - for they be the best corrected?

- Father - They be in my chest. Katherine, take the key of the closet...

- This plainly implies that musicians did not expect to rely on the notes as printed. __ Just plain Bill (talk) 15:53, 23 May 2013 (UTC)

- Adding to the difficulty of tracking things down is the occasionally notorious poor standard of proofreading in music engraving. Here is an Elizabethan example:

Stupid Question

As a non musician I have a stupid question. If there are seven natural notes (A to G inclusive) and each has a sharp and a flat then how do 21 notes (3*7) fit into a 12 note scale?

Given some of the comments above, and apparently by musically qualified people, I don't think I'm the only one confused by the notation. When are musicians going to come up with a clear, logical system of notation?--Quentin Durward (talk) 10:35, 30 May 2008 (UTC)

- About the same time that English shifts to a klir, lajikel sistem of spelling. The answer to your question is that there is some duplication, at least on modern instruments. So G sharp and A flat are the same note, called an enharmonic. —Wahoofive (talk) 16:15, 30 May 2008 (UTC)

- (both will likely never happen due to different tunings/pronunciations! e.g. "lajikel" doesn't work for me) Double sharp (talk) 15:49, 3 September 2013 (UTC)

As explained in the article, on equaled tempered keyboard instruments, an A flat and G sharp are indeed the same pitch, but in theory, they are 2 different pitches with slightly different pitches. On instruments like violin and most wind instruments, where the player has the ability to alter the pitch, it is possible for skilled players to play these 2 notes as different pitches, at least in theory. In the past, before equal temperament became standard for keyboard instruments, there were other tempering system that either required retuning if you played in a different key, or occasionally had things like split keys to be able to play both A flat and G sharp Wschart (talk) 02:26, 7 June 2008 (UTC)

Since 1700

After User:Jerome Kohl added a {{citation needed}} to the sentence "Since about 1700..." (along with a legitimate mention of Bach's later inconsistent use of the practice), I added a reference to the Harvard Dictionary, which actually says "In music prior to 1700 (probably even later) an accidental is not valid for the entire measure but only for the next note and immediate repetitions." Like all changes in musical notation (and everything else) the change took a while to disseminate. If somebody wants to rephrase the sentence, be my guest. —Wahoofive (talk) 23:54, 5 March 2014 (UTC)

- What I would like to know (and have not so far found a source for) is just when the practice of consistently carrying an accidental through the bar actually began. Bach isn't inconsistent—he clearly does not expect a player to repeat an accidental during a bar unless it is obviously necessary (and he occasionally leaves serious ambiguities—a famous example concerns a C♯, or lack thereof, in the Allemande of the Flute Partita, BWV 1013). The trick is, how "obvious" is "obvious"? The same is true in Handel's manuscripts, as well as in published editions of his music from his lifetime (i.e., the Walsh prints). I am not as familiar with Telemann's manuscripts, but I am reasonably au fait with the editions he engraved himself (Der getreue Musikmeister and Essercizi musici, at least), and again here the accidentals do not carry through the bar. It was never the case that accidentals always had to be notated every time they were meant to apply. An immediately repeated note is a good example, even in 14th-century music. A note recurring after one intervening note is nearly as clear, and certain cadential figures circulating around a leading tone also have never required a fresh accidental with every recurrence of the note. There may also be national differences as well as temporal ones. Although I have read from a fair number of French and Italian prints from the early 18th century (fewer manuscripts), I cannot at the moment recall whether they routinely repeat accidentals where we would not find this necessary, but I could easily check. The main difficulty (for me) is that my familiarity with these sources stops cold at about 1750. I have no idea what Haydn and Mozart's manuscript practice is in these matters, for example. Even if I did, however, this would all count as Original Research. The Harvard Dictionary is a good start, but vague. Perhaps the New Grove article on "Notation" is more precise, but I have not yet checked. I also have yet to see what the venerable Gardner Read book on notation does or does not say on the matter, but it lacks an index, which will slow down the investigation.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 02:23, 6 March 2014 (UTC)

- Further results: First, I cannot find the quotation cited from the Harvard Dictionary—at least, not in the third or fourth editions, nor in the 1999 Harvard Concise. In fact, all three say, "According to modern notational practice, an accidental remains in force for all notes occurring on the same line or space in the remainder of the measure in which it appears. This practice is not well established until the 19th century." Second, I find a phrase remarkably similar to the cited quotation in the article "Accidental" by Anthony Pryer in The Oxford Companion to Music (2002 revised edition), only with an interesting additional remark: "in music before 1700 (and some even later) an accidental is not valid for the entire bar but only for the note before which it occurs and for immediate repetitions of the same note (a practice observed by Bach)." Third, I find an intriguing inversion of the situation described in David Hiley's article "Accidental" in the New Grove (second edition, 2001): "not until the end of the 17th century were bar-lines generally understood to terminate the effect of accidentals." Geoffrey Chew and Richard Rastall give the most ample account, in §III, 4: "Mensural Notation from 1500" from the New Grove (2001) article "Notation", where they also offer Robert Donington as a supporting source:

From all this it would appear that the convention is completely unknown before 1700 and does not become generally accepted until about 1800, while during the 18th century the practice only gradually became more common. Regional variation is still to be investigated. Perhaps Donington has something to say on the subject.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 05:08, 6 March 2014 (UTC)For a similar reason, and because bar-lines were not used in the modern way until a late date, absolute consistency in the notation of accidentals – with a rule that accidentals are required only as shown, and that they hold good until the end of the bar – is not generally found before the 18th century or even the 19th. An accidental before the late 18th century generally applies only to the note next to which it is written or to notes in its immediate vicinity (see Donington, Interpretation, 3/1974, pp.131ff). Even as late as the early 19th century, for example in keyboard music printed in London, accidentals may be provided for only one note of an octave, with the performer expected to supply the second. Here as in other aspects of the notation simplicity was thought more desirable than precision.

- Further results: First, I cannot find the quotation cited from the Harvard Dictionary—at least, not in the third or fourth editions, nor in the 1999 Harvard Concise. In fact, all three say, "According to modern notational practice, an accidental remains in force for all notes occurring on the same line or space in the remainder of the measure in which it appears. This practice is not well established until the 19th century." Second, I find a phrase remarkably similar to the cited quotation in the article "Accidental" by Anthony Pryer in The Oxford Companion to Music (2002 revised edition), only with an interesting additional remark: "in music before 1700 (and some even later) an accidental is not valid for the entire bar but only for the note before which it occurs and for immediate repetitions of the same note (a practice observed by Bach)." Third, I find an intriguing inversion of the situation described in David Hiley's article "Accidental" in the New Grove (second edition, 2001): "not until the end of the 17th century were bar-lines generally understood to terminate the effect of accidentals." Geoffrey Chew and Richard Rastall give the most ample account, in §III, 4: "Mensural Notation from 1500" from the New Grove (2001) article "Notation", where they also offer Robert Donington as a supporting source:

Thank you for doing more homework on this. I've upgraded the citation, although you're right that Harvard Dictionary is a pretty minimal source. There's probably no definitive way to document the dissemination of that kind of change, and it probably isn't that important for this article. There's no reason at all to set a specific date; we may as well just say "starting in the 18th century". Also, maybe this should be moved to the "History" section. —Wahoofive (talk) 16:50, 6 March 2014 (UTC)

- The "homework" is what I do—that is, when an interesting question like this comes up, I want to know the answer and generally have got the machinery at my disposal to help me find it. Thanks for identifying the edition of the Harvard Dictionary used to support that claim. Unfortunately, it appears that the new editor, Don Michael Randel, has a very different idea about this, as do a number of other references. As a result, the current wording misleadingly presents an out-of-date view on the subject, and will need to be corrected. As you say, however, this particular detail really belongs in the "history" section, where it should probably be amplified with a mention of the use of the "retrospective" effect of accidentals found especially in the 15th to 17th centuries, but lingering somewhat into the 18th. I will need to get my hands on Donington's Interpretation of Early Music (which for some reason is not in my personal collection of books), which the GoogleBooks "snippet view" shows to be very promising on the subject—also on the effect of accidentals carrying through the barline, though I believe this sort of nonsense stops around 1700.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 19:34, 6 March 2014 (UTC)

- "Nonsense" seems a little harsh — musicians were expected to use their judgment in determining how to perform music (cf musica ficta); that's why so many early music compositions don't have tempo markings, for example. When performing music by Charpentier or Corelli it's pretty easy to determine which notes should get accidentals even if they're not all marked, but as Bach (and others) developed more adventuresome harmony, they needed more detailed notation. The same goes for double dots, sophisticated triplet notation, dynamic markings, etc. Vague notation was okay earlier on because they trusted performers to exercise judgment. —Wahoofive (talk) 07:12, 7 March 2014 (UTC)

- By "nonsense" I meant the practice of having the force of accidentals carry through the barline, though your point still applies. I blame it all on the lamentable decline in music education since the 17th century.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 07:40, 7 March 2014 (UTC)

- "Nonsense" seems a little harsh — musicians were expected to use their judgment in determining how to perform music (cf musica ficta); that's why so many early music compositions don't have tempo markings, for example. When performing music by Charpentier or Corelli it's pretty easy to determine which notes should get accidentals even if they're not all marked, but as Bach (and others) developed more adventuresome harmony, they needed more detailed notation. The same goes for double dots, sophisticated triplet notation, dynamic markings, etc. Vague notation was okay earlier on because they trusted performers to exercise judgment. —Wahoofive (talk) 07:12, 7 March 2014 (UTC)

Names for microtonal accidentals

I want to find out how to call the quartertone accidentials and realize that there are different names in use within Wikipedia. The article Flat_(music) mentions:

- half flat

- three-quarter flat

- sesquiflat

The article Sharp_(music) mentions:

- half sharp

- three-quarter sharp

The article Accidental_(music) mentions:

- half‑sharp

- sharp‑and‑a‑half

- half‑flat

- flat‑and‑a‑half

Wiktionary claim that "sesqui-" means "one and a half" (which is not three-quarter). The online documentation of Lilypond mentions:

- semiflat

- 3/2 flat

- sesquiflat

- semisharp

- 3/2 sharp

- sesquisharp

If anyone feels confident enough to decide which of these alternative names are correct, in use and relevant, he might edit all Wikipedia articles accordingly. It would be nice to have a common standard throughout articles and to list all relevant names.

My own (very limited) experience is that in modern scores many more graphical signs are in use to indicate pitch than are listed here. However, publishers rather describe what the symbols mean and how to play them and not how to call them. Nevertheless, names are important to talk about things or to search the internet, and an Encyclopedia like Wikipedia should help in this respect. --78.53.235.72 (talk) 13:08, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

- There is no established terminology in this case, just as there is no agreement on one set of symbols Therefore, all of these terms may be regarded as valid within their own contexts. The difficulty, of course, is not to mix them indiscriminately. For what it is worth, "sesqui" (properly, "sesquialterum") does indeed mean "one and a half", and one-and-a-half semitones is three-quarters of a whole tone. This is probably the sense of the terms "sequiflat" and "sesquisharp", but these are not terms with which I am familiar.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 20:55, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

Scores without measures

The basic rule is very clear, as stated in the article: "In the measure (bar) where it appears, an accidental sign raises or lowers the immediately following note (and any repetition of it in the bar) [...]". However, what is the case, if the scores notation is metrically unstructured, i.e. there are no measures or bars. I have never been taught or read a rule for this case even though I have encountered pieces of music for which it was not obvious for me how to interpret accidentals due to lack of bar lines.

I suspect that for scores not being arranged in measures the accidental applies only to the single note that immediately follows. Such a rule would be useful because a few staffs (or pages) later the performer might not remember previous accidentals any more. If anyone can confirm this rule and provide a good reference, it could be included in the article.

In principle, there could be alternative interpretations, e.g. an accidental being valid until the end of the staff line or musical phrase (provided the respective piece of music comprises musical phrases).

In case there is no general rule or that the correct way how to interpret accidentals in such cases depends on the editor, musical style or epoch this might be also worth being mentioned in the article. --92.224.202.34 (talk) 10:37, 1 October 2016 (UTC)

- In early music without barlines, I think it's safe to say that the accidental only applies to the immediate note (even in early barred music in the 17th century this was also true) — in Gregorian chant it would apply to the entire neume — and we could easily find references for that. For modern music without barlines there probably is no documented rule, so we can't really say much about it here in Wikipedia without falling afoul of the no research rule. It's not our business to speculate on WP. Undoubtedly we could find some individual composers who have specified how their own music is to be interpreted in such cases. —Wahoofive (talk) 06:04, 2 October 2016 (UTC)

"B"?

As one who is largely ignorant about musical matters and trying to learn: it says the symbol comes from the "b" used on Georgian chant manuscripts. Why "b"? What does it mean? Also, where it discusses "note-for-note" accidentals "to reduce the number of accidentals used", it appears to my unknowing eyes to be restating the exact same set of circumstances as associated with normal accidentals. Indeed, it appears you would need to use MORE of them since they now do NOT apply to two notes tied together. There is obviously some basic piece of information missing somewhere here (or at least I am missing it)..

64.223.144.161 (talk) 22:41, 12 June 2019 (UTC)

- The origin of the "b" is explained in the section History of notation of accidentals. It looks like the first rule of the note-for-note system was changed. It should just say "Accidentals affect only those notes which immediately precede." Squandermania (talk) 00:46, 16 June 2019 (UTC)

- Or even, "which immediately follow", but I see that you havefixed this problem already. Cheers, Squandermania.—Jerome Kohl (talk) 03:55, 16 June 2019 (UTC)

Do accidentals affect the staff position an octave away?

"Since about 1700, accidentals have been understood to continue for the remainder of the measure in which they occur, so that a subsequent note on the same staff position is still affected by that accidental, unless replaced by an accidental of its own. Notes on other staff positions, including those an octave away, are unaffected."

I do not claim to be the world's biggest music expert, but my understanding is that the position an octave away would be affected by the same accidental. So if middle C is sharped by an accidental, and then the C an octave above that were to appear later in the same measure with no accidental, it woul also be sharped. Maybe this is just something where different people have different standards, though. I also had the understanding that if the key signature has F sharped, then an F with a flat symbol would still be F-flat, not F-natural, although I can see how the latter standard would aid in sight transposition. GLmathgrant 18:20, 7 January 2007 (UTC)

- For your first question, accidentals only affect their own octave. If a C in one octave is sharped, a subsequent C in another octave in the same measure must have a sharp; however, if it's not meant to be sharped, most editors consider a courtesy natural mandatory. In jazz it's quite common for a note to have different accidentals in different octaves, even in the same chord (e.g. an A7-alt chord would contain both a C sharp and a C natural), although editorial standards in jazz notation are, shall we say, lax.

- An F with a flat sign in a piece whose key signature contains an F sharp (or when an F is sharped earlier in the measure) is considered an F-flat in modern notation, but in 17th- and 18th-century notation it often meant F-natural. —Wahoofive (talk) 22:40, 7 January 2007 (UTC)

That is untrue^^^^^^ Music Theory: If a note has an accidental and the note is repeated in a different octave within the same measure, the accidental applies to the same note of the different octave. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 72.188.164.224 (talk) 22:23, 4 December 2014 (UTC)

- Depends on who you are reading, and may depend on whether you are writing for keyboard or for some other instrument or voice. What is your source for this?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 22:29, 4 December 2014 (UTC)

I'm finding that most single voice music I see assumes an accidental applies to other octaves, and it constantly throws me. In polyphonic music -- say Bach fugues on a keyboard -- it is most natural to have accidentals not affect subsequent notes in other voices, whether they are in the same stave or not. Patrick Paulson patrick@3rivers-asthanga.org. — Preceding unsigned comment added by 71.95.123.179 (talk) 18:23, 23 July 2020 (UTC)

- Yes, yes, your opinion is noted but, as previously asked, do you have a reliable source for this?—Jerome Kohl (talk) 07:32, 24 July 2020 (UTC)

Rules for what accidentals to use

What I came here to find, and did not, is a statement about whether any rules or conventions govern the use of accidentals in a particular key/key signature when a note does not "belong" to the given key signature. If such rules exist, what are they? For example, if I'm writing a piece in G, my staff is using the G/Em key signature, and I want someone to play the black key between D and E, do I speak of (and notate) D sharp or E flat? And, more importantly, why? To put the question another way, why is there a double sharped F in the Nocturne example, and not a G natural? Even if the answer is, "it's just willy nilly", then I think there ought to be some sort of statement about that. --Trweiss (talk) 18:51, 1 September 2009 (UTC)

- The answer is, generally, that one uses the accidental that will cause least confusion. For instance, accidentals are often part of a temporary modulation. In your example of a piece in G, the note D#/Eb would suggest a temporary modulation to E minor, and so would be written as D#. The reason is that it's likely there will be other Es close by (E being common to both the old and new keys), but not other Ds, so if you wrote it as Eb you'd have to keep flattening it and naturalling it every time an E-natural came up. 91.105.42.143 (talk) 16:54, 16 February 2010 (UTC)

- I agree with the "least confusion" part, and would add "least extra ink" to that. Example, a piece in G major that modulates to D for a while, using accidental C sharps instead of D flats, since D is used in both keys. Avoids thrashing around between D natural and D flat. __Just plain Bill (talk) 17:36, 16 February 2010 (UTC)

With the above (specifically, "whatever causes the least confusion") in mind, I find myself disagreeing with the following statement:

- Note that in a few cases the accidental might change the note by more than a semitone: for example, if a G sharp is followed in the same measure by a G flat, the flat sign on the latter note means it will be two semitones lower than if no accidental were present. Thus, the effect of the accidental has to be understood in relation to the "natural" meaning of the note's staff position. For the sake of clarity, some composers put a natural in front of the accidental. Thus, if in this example the composer actually wanted the note a semitone lower than G-natural, he might put first a natural sign to cancel the previous G-sharp, then the flat.

In my mind, and in my somewhat out-of-practice experience, it would be far more normal, and far clearer to notate the G-flat as an F-sharp. Please do correct me if I'm wrong, but I'd suggest that even if you do want to keep the above block of text as an example of why you might have a G-natural-flat noted down, it would still be worth saying that a simple F-sharp exists as an alternative? I've made the edit, although please do revert if I've misunderstoodGGdown (talk) 15:34, 12 April 2011 (UTC)

- I'm not sure that is entirely correct. The spelling of the note usually has more to do with its relationship in the chord than what appears previously in the measure. --dbolton (talk) 23:06, 14 April 2011 (UTC)

- Not too hard to come up with a plausible context:

- F♯ here would be grammatically wrong. For clarity, I'd probably write a natural-flat rather than a single flat, though. Double sharp (talk) 09:09, 17 September 2021 (UTC)

- Great example, DS, though I'm not sure why you thought a ten-year-old thread needed an example. (Beethoven's Eroica Symphony, which is in E-flat major but incorporates a C-sharp by the seventh bar, would be another. We can argue all day whether that C-sharp should become a D-flat in the recapitulation, where it resolves to a C natural.) The whole premise of the question, though, assumes there's some official set of "rules" that govern notation, and that's just not so. People wrote stuff down, and the rule-makers came later. —Wahoofive (talk) 23:37, 1 December 2021 (UTC)

- Well, I thought it was non-obvious enough that curious people like me reading through the talk page might want to see an example, even if the thread is long since over. Though GGdown's question was about why one would want to write a G-sharp and a G-flat in the same bar, so I guess the Eroica doesn't really count. :) Double sharp (talk) 00:34, 2 December 2021 (UTC)

- Great example, DS, though I'm not sure why you thought a ten-year-old thread needed an example. (Beethoven's Eroica Symphony, which is in E-flat major but incorporates a C-sharp by the seventh bar, would be another. We can argue all day whether that C-sharp should become a D-flat in the recapitulation, where it resolves to a C natural.) The whole premise of the question, though, assumes there's some official set of "rules" that govern notation, and that's just not so. People wrote stuff down, and the rule-makers came later. —Wahoofive (talk) 23:37, 1 December 2021 (UTC)

- F♯ here would be grammatically wrong. For clarity, I'd probably write a natural-flat rather than a single flat, though. Double sharp (talk) 09:09, 17 September 2021 (UTC)

Hey, I figured out how to get the notation I wanted thanks to an old Music Stack Exchange question!

It's old-fashioned notation, but for me it's the clearest. Maybe not for those more used to modern-style accidental behaviour, though. Double sharp (talk) 00:45, 2 December 2021 (UTC)

Accidentals on ties

- In fact, repeating accidentals on tied notes passing through line- or page-breaks is not only a convention used for atonal music. Some style guides think it is preferable. If you do this, then you don't need to repeat the accidental if the note then repeats immediately. See for example the Eulenberg edition of Haydn's Quartet Op. 76 No. 1 – the passage bb.187–190 in the three upper parts shows how it works.

- Is there actually a rule for what a note without an accidental after a cross-barline tie means? It seems horribly ambiguous. Double sharp (talk) 22:14, 31 May 2022 (UTC)

- OK, Gardner Read's Music Notation says there is (pp. 130–1):

The accidental-as-reminder functions significantly when a note affected by an accidental is tied across a barline. In such cases the accidental remains in full effect until the conclusion of the tie, regardless of its length. It does not affect a repetition of the same pitch following the tied note. Alert performers will, of course, remember that barlines have intervened, and that the accidental does not affect the repetition of the same pitch following the tied note. But because the player's eye—seeing another note on the same line or space—might mislead him into repeating the accidental, it is wise to put in any desired natural sign, in parentheses, as a gentle reminder.

Double sharp (talk) 09:29, 3 October 2022 (UTC)

- OK, Gardner Read's Music Notation says there is (pp. 130–1):

Double accidentals in 1615

The claim that double accidentals arose in 1615 is dubious. The cited source is clearly a circular reference, added after the claim in this article had had a "citation needed" tag for ten years. Over 100 years later, musicians were still using additive single accidentals where modern practice would call for double accidentals; see Bach's WTC. (Some manuscripts use the newly invented x-shaped double sharp sign, but others use single sharp accidentals that add to the sharp in the key signature, and all use the second approach for flats.) Keys in which double accidentals might reasonably appear were not yet in use in 1615. I have accordingly removed the claim from the article. Phoogenb (talk) 08:29, 27 March 2024 (UTC)