Pentamerone

The Pentamerone, subtitled Lo cunto de li cunti ("The Tale of Tales"), is a seventeenth-century Neapolitan fairy tale collection by Italian poet and courtier Giambattista Basile.

Background

[edit]The stories in the Pentamerone were collected by Basile and published posthumously in two volumes by his sister Adriana in Naples, Italy, in 1634 and 1636 under the pseudonym Gian Alesio Abbatutis. These stories were later adapted by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, the latter making extensive, acknowledged use of Basile's collection. Examples of this are versions of Cinderella, Rapunzel, Puss in Boots, Sleeping Beauty, and Hansel and Gretel.

While other collections of stories have included stories that would be termed fairy tales, his work is the first collection in which all the stories fit in that single category.[1] He did not transcribe them from the oral tradition as a modern collector would, instead writing them in Neapolitan, and in many respects was the first writer to preserve oral intonations.[2]

The style of the stories is heavily Baroque, with many metaphorical usages.[3]

This has been interpreted as a satire on Baroque style, but as Basile praised the style, and used it in his other works, it appears to have no ironic intention.[4]

Influence

[edit]Although the work fell into obscurity, the Brothers Grimm, in their third edition of Grimm's Fairy Tales, praised it highly as the first national collection of fairy tales, fitting their romantic nationalist views on fairy tales, and as capturing the Neapolitan voice. This drew a great deal of attention to the work.[5]

This collection (Basile's Pentamerone) was for a long time the best and richest that had been found by any nation. Not only were the traditions at that time more complete in themselves, but the author had a special talent for collecting them, and besides that an intimate knowledge of the dialect. The stories are told with hardly any break, and the tone, at least in the Neapolitan tales, is perfectly caught.... We may therefore look on this collection of fifty tales as the basis of many others; for although it was not so in actual fact, and was indeed not known beyond the country in which it appeared, and was never translated into French, it still has all the importance of a basis, owing to the coherence of its traditions. Two-thirds of them are, so far as their principal incidents are concerned, to be found in Germany, and are current there at this very day. Basile has not allowed himself to make any alteration, scarcely even any addition of importance, and that gives his work a special value – Wilhelm Grimm

Basile's writing inspired Matteo Garrone's 2015 film, The Tale of Tales.[6]

Geography of the stories

[edit]The tales of Giambattista Basile are set in Basilicata and Campania, where he spent most of his life at the local nobles. Among the places related to the stories we find the city of Acerenza and the Castle of Lagopesole, the latter connected to the fairy tale Rapunzel.

Synopsis

[edit]The name of the Pentamerone comes from Greek πέντε [pénte], 'five', and ἡμέρα [hêméra], 'day'. It is structured around a fantastic frame story, in which fifty stories are related over the course of five days, in analogy with the ten-day structure of the much earlier Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio (1353). The frame story is that of a cursed, melancholy princess named Zoza ("mud" or "slime" in Neapolitan, but also used as a term of endearment). She cannot laugh, no matter what her father does to amuse her, so he sets up a fountain of oil by the door, thinking people slipping in the oil would make her laugh. An old woman tried to gather oil, a page boy broke her jug, and the old woman grew so angry that she danced about, and Zoza laughed at her. The old woman cursed her to marry only the prince of Round-Field, whom she could only wake by filling a pitcher with tears in three days. With some aid from fairies, who also give her gifts, Zoza found the prince and the pitcher, and nearly filled the pitcher when she fell asleep. A Moorish slave steals it, finishes filling it, and claims the prince.

This frame story in itself is a fairy tale,[7] combining motifs that will appear in other stories: the princess who cannot laugh in The Magic Swan, Golden Goose, and The Princess Who Never Smiled; the curse to marry only one hard-to-find person, in Snow-White-Fire-Red and Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa; and the heroine falling asleep while trying to save the hero, and then losing him because of trickery in The Sleeping Prince and Nourie Hadig.

The now-pregnant slave-princess demands (at the impetus of Zoza's fairy gifts) that her husband tell her stories, or else she would crush the unborn child. The husband hires ten female storytellers to keep her amused; disguised among them is Zoza. Each tells five stories, most of which are more suitable to courtly, rather than juvenile, audiences. The Moorish woman's treachery is revealed in the final story (related, suitably, by Zoza), and she is buried, pregnant, up to her neck in the ground and left to die. Zoza and the Prince live happily ever after.

Many of these fairy tales are the oldest known variants in existence.[8]

The fairy tales are:

- The First Day

-

- "The Tale of the Ogre"

- "The Myrtle"

- "Peruonto" - connected to Russian tale "At the Pike's Behest" ("Emelian the Fool")

- "Vardiello"

- "The Flea"

- "Cenerentola" – translated into English as Cinderella

- "The Merchant"

- "Goat-Face"

- "The Enchanted Doe" - a variant of The Knights of the Fish

- "The Flayed Old Lady" - variant of The King Who Would Have a Beautiful Wife

- The Second Day

-

- "Parsley" – a variant of Rapunzel

- "Green Meadow" - variant of The Bird Lover

- "Violet"

- "Pippo" – a variant of Puss In Boots

- "The Snake"

- "The She-Bear" – a variant of Allerleirauh

- "The Dove" – a variant of The Master Maid

- "The Young Slave" – a variant of Snow White

- "The Padlock"

- "The Buddy"

- The Third Day

-

- "Cannetella"

- "Penta of the Chopped-off Hands" – a variant of The Girl Without Hands

- "Face"

- "Sapia Liccarda"

- "The Cockroach, the Mouse, and the Cricket" - variant of The Princess Who Never Smiled

- "The Garlic Patch"

- "Corvetto"

- "The Booby"

- "Rosella"

- "The Three Fairies" – a variant of Frau Holle

- The Fourth Day

-

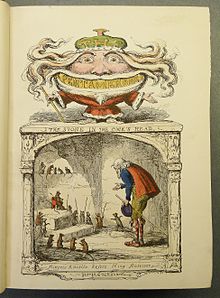

- "The Stone in the Cock's Head"

- "The Two Brothers"

- "The Three Enchanted Princes"

- "The Seven Little Pork Rinds" – a variant of The Three Spinners

- "The Dragon"

- "The Three Crowns"

- "The Two Cakes" – a variant of Diamonds and Toads

- "The Seven Doves" – a variant of The Seven Ravens

- "The Raven" – a variant of Trusty John

- "Pride Punished" – a variant of King Thrushbeard

- The Fifth Day

-

- "The Goose"

- "The Months"

- "Pintosmalto" – a variant of Mr Simigdáli

- "The Golden Root" – a variant of Cupid and Psyche

- "Sun, Moon, and Talia" – a variant of Sleeping Beauty

- "Sapia"

- "The Five Sons"

- "Nennillo and Nennella" – a variant of Brother and Sister

- "The Three Citrons" – a variant of The Love for Three Oranges

Translations

[edit]The text was translated into German by Felix Liebrecht in 1846, into English by John Edward Taylor in 1847 and again by Sir Richard Francis Burton in 1893 and into Italian by Benedetto Croce in 1925. Another English translation was made from Croce's version by Norman N. Penzer in 1934. A new, modern translation by Nancy L. Canepa was published in 2007 by Wayne State University Press, and was later released as a Penguin Classics paperback in 2016.

Adaptations

[edit]The 2015 Italian film Tale of Tales, directed by Matteo Garrone, is generally based on stories from the collection, starring Salma Hayek, Vincent Cassel and Toby Jones as protagonists of the tales "The Enchanted Doe", "The Flayed Old Lady" and "The Flea", respectively.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ Croce 2001, p. 879.

- ^ Croce 2001, pp. 880–881.

- ^ Croce 2001, p. 881.

- ^ Croce 2001, p. 882.

- ^ Croce 2001, pp. 888–889.

- ^ a b Vivarelli 2014.

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. A Guide to Folktales in the English Language: Based on the Aarne-Thompson Classification System. Bibliographies and Indexes in World Literature, vol. 11. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1987. p. 144. ISBN 0-313-25961-5.

- ^ Swann Jones 1995, p. 38.

Sources

[edit]- Croce, Benedetto (2001). "The Fantastic Accomplishment of Giambattista Basile and His Tale of Tales". In Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. New York: W W Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-97636-6.

- Swann Jones, Steven (1995). The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination. New York: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-0950-6.

- Vivarelli, Nick (15 May 2014). "Cannes: Italo Auteur Matteo Garrone Talks About His 'Tale of Tales' (Exclusive)". Variety. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Basile, Giambattista (2007). Giambattista Basile's "The Tale of Tales, or Entertainment for Little Ones". Translated by Nancy L. Canepa, illustrated by Carmelo Lettere, foreword by Jack Zipes. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2866-8.

- Canepa, Nancy L. (1999). From Court to Forest: Giambattista Basile's "Lo cunto de li cunti" and the Birth of the Literary Fairy Tale. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2758-6.

- Albanese, Angela, Metamorfosi del Cunto di Basile. Traduzioni, riscritture, adattamenti, Ravenna, Longo, 2012.

- Maggi, Armando (2015). Preserving the Spell: Basile's "The Tale of Tales" and Its Afterlife in the Fairy-Tale Tradition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-24296-5.

- Hurbánková, Šárka. (2018). "G. B. Basile and Apuleius: First literary tales. morphological analysis of three fairytales". In: Graeco-Latina Brunensia. 23: 75–93. 10.5817/GLB2018-2-6.

- Praet, Stijn. "“Se lieie la favola”: Apuleian Play in Basile's Lo cunto de li cunti". In: International Journal of the Classical Tradition 25: 315–332 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12138-017-0454-6

External links

[edit]- Zipes, Jack (2002). "Pentamerone". The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860509-6. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- "La vita di Giambattista Basile" (in Italian)

- The complete text of Lo cunto de li cunti (in Neapolitan)

- Works by Giambattista Basile at Project Gutenberg

- Illustrations by Warwick Goble

- Illustrations Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine by George Cruikshank

- Professor S. Cicciotti's page about G. B. Basile (in Italian)

- Online text of some stories, in English (from Taylor translation)