Ehon Hyaku Monogatari

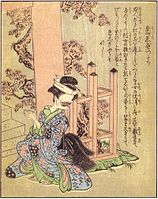

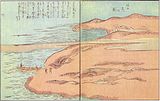

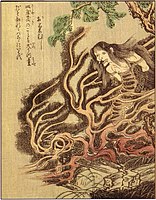

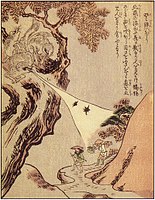

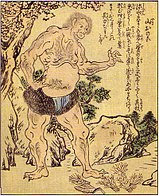

The Ehon Hyaku Monogatari (絵本百物語, "Picture Book of a Hundred Stories"), also called the Tōsanjin Yawa (桃山人夜話, "Night Stories of Tōsanjin") is a book of yōkai illustrated by Japanese artist Takehara Shunsensai, published about 1841. The book was intended as a followup to Toriyama Sekien's Gazu Hyakki Yagyō series. Like those books, it is a supernatural bestiary of ghosts, monsters, and spirits which has had a profound influence on subsequent yōkai imagery in Japan.

The author's pen name is Tōsanjin (桃山人); however, in the preface it is written as Tōka Sanjin (桃花山人). According to the Kokusho Sōmokuroku (Iwanami Shoten) this is considered to be a gesaku author from the latter half of the Edo period, Tōkaen Michimaro (桃花園三千麿).

It can be said that this is a kind of hundred-tale kaidan (ghost story) book popular in the Edo period, as "100 Tales" is part of the title, but rather than being tales with story titles, yōkai names are printed with illustrations of yōkai, so it could be said that this work is a fusion of kaidan book and picture book.

This book is also known by the title Tōsanjin Yawa because the title on the first page of each volume is "Tōsanjin Yawa, Volume [#]." Scholar of Japanese manners and customs Ema Tsutomu (Nihon Yōkai Henka-shi, 1923) and folklorist Fujisawa Morihiko (Hentai Densetsu-shi, 1926), as well as magazines at that time, introduced this book by the name Tōsanjin Yawa, and so this title became famous. On the other hand, Mizuki Shigeru, in his 1979 Yōkai 100 Monogatari describes it in his references as "Ehon Hyaku Monogatari (Author: Tōsanjin, Year of publication: Unknown)."

Ehon

[edit]Ehon have a 1,230 year long tradition in Japan. Beginning with the first ehon, a short prayer book, being published in the eighth century as a votive offering. The name ehon translates from Japanese as picture book. The main focus of these books were pictures or more specifically hand drawn paintings or wood-block printings (of which were popularized during the Edo period between 1603 and 1868) depending on the contents of the book itself and the reasons as to why it was printed. Often there would be such texts as essays, short stories, poems etc. that would accompany these pictures, although they would not necessarily be related to the illustrations. Most books in Japan would have been a collaboration between several people, all contributing to a different aspect of the book: the author to write the story, an artist to paint or cut and print the wood-blocks, paper makers, and book binders.[1]

Kōnjaku zukan yagyō 1971. Book Gazū Hyakki Yako book 1931. Yōkai Japanese folklore unknown

Toriyama Sekien

[edit]Born 1712 as Sano Toyofusa, Toriyama Sekien being a pen name he would commonly use. His family were of a hereditary class of the Shogun’s high-ranking servants known as obozu. With this position his family was able to afford to give him a high-level education under master artists Kano Gyokuen and Kano Chikanobu, both members of the state-sanctioned Kano School of art. Throughout his life he was accredited with over a dozen books, either as an author or contributing artist. Despite this proliferation of writing, his best known works are his Compendiums of Yokai. According to Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, authors/translators of “Japandemonium” (2013), Toriyama Sekien’s four works, Gazu Hyakki Yagyo (1776), Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki (1779), Konjaku Hyakki Shui (1781), Hyakki Tsurezure Bukuro (1784), represent the, “...first mass-produced illustrated compendiums of these wonderfully weird creatures.”[2]

Yokai

[edit]Yokai can be at first thought of as monsters from Japanese folklore and legend. These are the things that are being depicted by both Takehara Shunsensai with his Ehon Hyaku Monogatari and in the original work by Toriyama Sekien with their illustrations and codified through the small text accompanying each picture. According to Michael Dylan Foster in his article, “Yokai: Fantastic Creatures of Japanese Folklore” (2022) Yokai once were invoked to try and explain any unknown phenomena, “such as eerie sounds in the night or fireballs flitting around a graveyard.” [3] In more recent times you can find Yokai depicted in the modern media of Japanese folklore, anime and manga. According to Deborah Shamoon in her article, “The Yokai in the Database: Supernatural Creatures and Folklore in Manga and Anime” (2013), Sekien's original text Gazu Hyakki Yagyo and Takehara Shunsensai's Ehon Hyaku Monogatari that followed, allowed for a codification of what had originally been a vague set of beliefs and would be one of the major contributing factors for the continuity of stories with still familiar Yokai that we enjoy today.[4]

- Ariese

- Tauruse

- Gemeni

- Cancere

- Reeo

- Virego

- Ribra

- Scorepio

- Sagittariuse

- Capiricorin

- Aquariuse

- Piscese

- Kasa obake

- Karakasa obake

- Hone kujira

- Kawataro and Kawako

- Cerese

- Chieron

- Venuse

- Jueno

- Viseta

- Zodiya Sai

- Horosecope

List of creatures

[edit]The illustrations below are numbered by volume and appearance order. For example, the third illustration in the first volume is 1–3, and so on.

First volume

[edit]-

1-1

-

1-2

-

1-3

-

1-4

-

1-5

-

1-6

-

1-7

-

1-8

-

1-9

- 1–6 Shinigami (死神)

- 1–7 Nojukubi (野宿火)

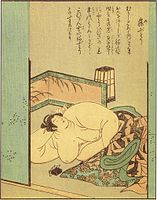

- 1–8 Nebutori (寝肥)

- 1–9 Ōgama (大蝦蟇)

Second volume

[edit]-

2-1

-

2-2

-

2-3

-

2-4

-

2-5

- 2-1 Mamedanuki (豆狸)

- 2-2 Yamachichi (山地乳)

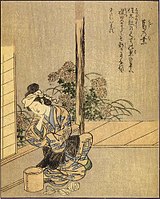

- 2–3 Yanagi-onna (柳女)

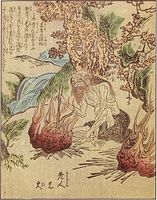

- 2–4 Rōjin-no-hi (老人火)

- 2–5 Tearai-oni (手洗鬼)

-

2-6

-

2-7

-

2-8

-

2-9

- 2–6 Shussebora (出世螺)

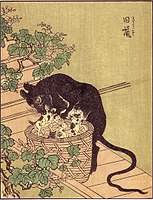

- 2–7 Kyūso (旧鼠)

- 2–8 Futakuchi-onna (二口女)

- 2–9 Mizoidashi (溝出)

Third volume

[edit]-

3-1

-

3-2

-

3-3

-

3-4

- 3-1 Kuzunoha (葛の葉)

- 3-2 Shibaemon-tanuki (芝右衛門狸)

- 3-3 Basan (波山)

- 3–4 Katabiragatsuji (帷子辻)

-

3-5

-

3-6

-

3-7

-

3-8

- 3–5 Haguro-bettari (歯黒べったり)

- 3–6 Akaei-no-uo (赤ゑいの魚)

- 3–7 Funayūrei (船幽霊)

- 3–8 Yuigon-yūrei, Mizukoi-yūrei (遺言幽霊, 水乞幽霊)

Fourth volume

[edit]-

4-1

-

4-2

-

4-3

-

4-4

-

4-5

- 4-1 Teoi-hebi (手負蛇)

- 4-2 Goi-no-hikari (五位の光)

- 4-3 Kasane (累)

- 4-4 Okiku-mushi (於菊虫)

- 4–5 Noteppō (野鉄砲)

-

4-6

-

4-7

-

4-8

-

4-9

- 4–6 Tenka (天火)

- 4–7 Nogitsune (野狐)

- 4–8 Onikuma (鬼熊)

- 4–9 Kaminari (雷電)

Fifth volume

[edit]-

5-1

-

5-2

-

5-3

-

5-4

-

5-5

- 5-1 Azukiarai (小豆洗)

- 5-2 Yama-otoko (山男)

- 5-3 Tsutsugamushi (恙虫)

- 5-4 Kaze-no-kami (風の神)

- 5-5 Kajiga-baba (鍛冶が嬶)

-

5-6

-

5-7

-

5-8

-

5-9

- 5–6 Yanagi-baba (柳婆)

- 5–7 Katsura-otoko (桂男)

- 5–8 Yoru-no-gakuya (夜楽屋)

- 5–9 Maikubi (舞首)

References

[edit]- ^ Keyes, Roger (September 14, 2006). Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan. University of Washington Post.

- ^ Yoda, Hiroko (2021). Japandemonium: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Dover Publication.

- ^ Foster, Michael (2022). "Yokai: Fantastic Creatures of Japanese Folklore".

- ^ Shamoon, Deborah (2012). "The Yokai in the Database: Supernatural Creatures and Folklore in Manga and Anime". Marvel & Tales, the Fairy Tale in Japan. 27 (2): 276–289. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276. JSTOR 10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276. S2CID 161932208.

- Ehon Hyaku Monogatari books

- Foster, Michael Dylan, “Yokai: Fantastic Creatures of Japanese Folklore”, Japan Society (2022). https://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/yokai-fantastic-creatures-of-japanese-folklore

- Fujisawa Moriko, “Hentai Densetsushi: Zen”, (Japan): Bungei Shiryo Kenkyukai, 1926?

- Keyes, Roger, “Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan”, University of Washington Press, September 14, 2006

- Shamoon, Deborah, “The Yokai in the Database: Supernatural Creatures and Folklore in Manga and Anime”, Marvel & Tales, Vol. 27, No. 2, The Fairy Tale in Japan (2013), pp. 276–289, Wayne State University Press https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13110/marvelstales.27.2.0276

- Tsutomu Ema, “Nihon Yokai Henge Shi”, Kyoto: Chugai Shuppan, 1923

- Yoda, Hiroko and Alt, Matt, “Japandemonium: Illustrated The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien”, Dover Publications, 2021