Tokyo Drifter

| Tokyo Drifter | |

|---|---|

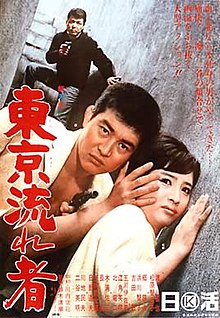

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Seijun Suzuki |

| Written by | Yasunori Kawauchi |

| Produced by | Tetsuro Nakagawa |

| Starring | Tetsuya Watari Chieko Matsubara Hideaki Nitani |

| Cinematography | Shigeyoshi Mine |

| Edited by | Shinya Inoue |

| Music by | Hajime Kaburagi |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Tokyo Drifter (東京流れ者, Tōkyō nagaremono) is a 1966 yakuza film directed by Seijun Suzuki. The story follows the reformed yakuza hitman "Phoenix" Tetsu, played by Tetsuya Watari, who is forced to roam Japan while avoiding execution by rival gangs.

Plot

[edit]Tokyo-based yakuza boss Kurata decides to disband his criminal organization and become a legitimate businessman. However, his old rival, Otsuka, sees his retirement as an opportunity to seize his businesses. Otsuka tries to recruit Kurata’s right-hand man, Tetsuya “Phoenix Tetsu” Hondo, into his organization but Tetsu rebuffs him out of loyalty to Kurata, earning Otsuka’s ire.

One of Otsuka’s men, Tanaka, gets a tip from his girlfriend, Mutsuko, that Kurata went into debt with her boss, Yoshii, to buy his primary business, Club Alulu. Otsuka visits Yoshii’s office and threatens him into selling Kurata’s debt to him so he can foreclose on it and take his properties. Though Yoshii initially resists, he eventually caves and signs the debt over. Tetsu learns of Otsuka’s intentions and goes to rescue Yoshii, but arrives after Otsuka has already killed the moneylender and is then taken captive. Otsuka goes to inform Kurata that he now owns his debt, prompting an argument which culminates with Otsuka’s men attacking Kurata, who draws his pistol and fires at them but accidentally hits and kills Mutsuko. Otsuka tries to use this to blackmail Kurata into handing over even more properties, but Tetsu arrives after having escaped from Kurata’s trap and threatens to expose Otsuka’s murder of Yoshii if Otsuka doesn’t leave his boss alone. Deadlocked, Kurata and Otsuka make Yoshii and Mutsuko’s deaths look like a lover’s suicide and the matter is temporarily resolved.

Infuriated by Tetsu’s foiling of his plan, Otsuka orders his top hitman, Tatsuzo the Viper, to kill him. Tetsu manages to avoid an attempt on his life during a date with his girlfriend, Club Alulu singer Chiharu, and then resolves to leave Tokyo to protect Kurata and Chiharu.

Tetsu travels north and is taken in by Kurata’s allies, the Nanbu Group, who are embroiled in a turf war with the Otsuka-allied Hokubu Group. However, he is forced to flee soon after when a group of Hokubu thugs led by Tatsuzo and Tanaka attack the Nanbu Group’s base. Tetsu manages to escape his pursuers while inflicting severe injuries to them, leaving Tanaka with a missing eye and Tatsuzo with a crushed hand and burnt face.

Tetsu eventually meets up with Kenji “Shooting Star” Aizawa, a former Otsuka man who defected from the group. Despite their prior enmity, Kenji lets Tetsu stay in his home and helps tend to his wounds. When speaking about their respective exiles, Kenji warns Tetsu not to put too much trust in Kurata, since he believes all yakuza bosses care more about their wealth than their underlings, something which the ever-loyal Tetsu rejects.

After he recovers, Tetsu tries to avoid his pursuers by changing course and heading south. En route, he briefly runs into Chiharu, who’s been trying to find him, but he rejects her efforts to reunite and get him to come back home with her.

Arriving in Sasebo, Tetsu is taken in by Kenji’s new boss, the Kurata-aligned Umetani. While Tetsu speaks with Umetani at his western film-themed saloon, Tatsuzo arrives and starts a brawl to cover for another attempt on Tetsu’s life. However, Kenji protects Tetsu from Tatsuzo's assassination and, after Tetsu and Umetani drive out the rioting patrons, the three confront him. Cornered, Tatsuzo shoots himself to avoid being killed by his enemies.

Due to the humiliation Tetsu has inflicted on his organization, Otsuka offers to forgive Kurata’s debt and let him keep his businesses in exchange for aiding in killing Tetsu, to which Kurata agrees. Kurata orders Umetani to kill Tetsu for him, but he and Kenji refuse to obey the order and instead warn Tetsu, who decides to return to Tokyo. Tetsu confronts Kurata and Otsuka at Club Alulu, where they are hearing Chiharu perform, resulting in a shootout in which Otsuka and all of his men (including Tanaka) are killed. Ashamed of his betrayal, Kurata slits his own wrists to commit suicide in atonement. As Tetsu leaves, Chiharu offers to travel with him, but he rejects her pleas, explaining he has become a wanderer and cannot be accompanied by anyone. He then steps out of the club and walks off into the night.[1]

Cast

[edit]- Tetsuya Watari as Tetsuya "Phoenix Tetsu" Hondo

- Chieko Matsubara as Chiharu

- Ryūji Kita as Boss Kurata

- Hideaki Esumi as Boss Otsuka

- Tamio Kawaji as Tatsuzo the Viper

- Hideaki Nitani as Kenji "Shooting Star" Aizawa

- Eiji Go as Tanaka

- Isao Tamagawa as Boss Umetani

- Michio Hino as Yoshii

- Tomoko Hamakawa as Mutsuko

- Tsuyoshi Yoshida as Keiichi

Production

[edit]Nikkatsu bosses had been warning Suzuki to tone down his bizarre visual style for years and drastically reduced Tokyo Drifter's budget in hopes of getting results. This had the opposite effect in that Suzuki and art director Takeo Kimura pushed themselves to new heights of surrealism and absurdity. The studio's next move was to impose the further restriction of filming in black and white on his next two films, which again Suzuki met with even greater bizarreness culminating in his dismissal for "incomprehensibility".[2]

Because of budget limitations, Suzuki had to cut connecting shots out of many fights, leading to a need for more creative camera work.[3]

Various shots of Tokyo were used to establish the setting as the then-contemporary post-1964 Japan.[4] Suzuki drew inspiration from a wide variety of sources in making Tokyo Drifter, including the musical films of the 1950s, pop art, absurdist comedy, and surrealist film.[5]

Themes

[edit]Suzuki displays common themes found in yakuza films, particularly the theme of loyalty, in order to parody the message and presentation of traditional yakuza films. He uses his depictions of yakuza relationships to show the inherent weakness of the archetype, particularly the possible abuses of power that can arise from unquestioning allegiance.[4] Further, the common theme of corporate corruption is also parodied through exaggeration when the main character becomes an expendable retainer.[6] The conventions in the film further parody the conformity of theme and structure apparent in all Japanese film, but especially in yakuza films of the time,[5] particularly its excesses.[7]

Style

[edit]The mise en scène of Tokyo Drifter is highly stylized.[8] Film reviewer Nikolaos Vryzidis claims that the film crosses over into a number of different genres, but most resembles the avant-garde films occurring in the 1960s.[5]

At times, the film draws a good deal of inspiration from westerns. The whistling of the main character Tetsu is reminiscent of cowboy heroes. Near the middle of the film, a large bar fight erupts; this scene is meant to directly parody western films, everyone in the saloon joins in the brawl against United States Navy sailors, and comical violence is used where no one is permanently injured, despite the large-scale violence of the scene.[9]

The majority of the film takes place in Tokyo, but portrays the city in a highly stylized manner.[10] The opening sequence consists of a mash of images from metropolitan Tokyo, meant to condense the feeling of the city into one sequence.[11]

The film opens in stylized black and white, which becomes vibrant color in all subsequent scenes.[9] This served to represent Tokyo post-1964 Summer Olympics.[11]

Reception

[edit]Vryzidis claims that Suzuki's later films, once the studio gave him more freedom, never reached the same level of artistic quality as Tokyo Drifter, where the studio attempted to impose a large amount of control over the project.[9] Tetsu, the main character of the film, has also been well received. One reviewer commented that he always looks "cool", even when he is not the toughest guy in the room.[7]

Stephen Barber called the visualization in Tokyo Drifter "bizarre and individual".[10] Douglass Pratt praised the film for its quirkiness and character.[3] He further stated that the plot of the film does not matter so much as "the gorgeous Pop Art sets, the bizarre musical sequences, the confusing but ballistic action scenes and the film's gunbutt attitude."[3]

Legacy

[edit]The film is considered ahead of its time, as it abandoned the themes of the Ninkyo eiga films popular at the time, and combines with themes from the later Jitsuroku eiga yakuza films, which disavowed the romantic and nostalgic views of the yakuza in favor of social criticism.[6]

Home video

[edit]The Criterion Collection released the film outside Japan in DVD format in 1999.[12] Criterion also released a Blu-ray version in 2013.

Soundtrack

[edit]The film has a recurrent appearance of Tetsu's girlfriend as a lounge singer repeating several times her signature song throughout the film.

Tokyo Drifter 2: The Sea is Bright Red as the Color of Love

[edit]| Tokyo Drifter 2: The Sea is Bright Red as the Color of Love | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Kenjirō Morinaga |

| Screenplay by | Keihan Ono, Daigo Mitsushiro |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Hajime Kaburagi |

| Distributed by | Nikkatsu |

Release date |

|

Running time | 73 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Tokyo Drifter 2: The Sea is Bright Red as the Color of Love (続東京流れ者 海は真っ赤な恋の色, Zoku Tōkyō nagaremono Umiwa Makkana Koinoiro) is a 1966 Japanese crime film and sequel to Tokyo Drifter.[13][14]

Cast

[edit]- Tetsuya Watari as Fushicho no Tetsu (Tetsuya Hondō)

- Kazuko Tachibana as Setsuko Toda

- Chieko Matsubara as Sally Kayama

- Teruo Yoshida as Kenji Gōda

- Keisuke Noro as Matsu

- Ryōtarō Sugi as Kōji Sugi

- Mari Shiraki as Hiromi

- Goro Tarumi as Ace no Hide (Shinji Toda)

- Shōbun Inoue as Onijima

- Nobuo Kaneko as Segawa

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Berra (2010), 282.

- ^ Desjardins (2005), 136–149.

- ^ a b c Pratt (2005), 1246.

- ^ a b Standish (2005), 300.

- ^ a b c Vryzidis (2010), 282.

- ^ a b Standish (2005), 301.

- ^ a b Bleiler (2004), 632.

- ^ Standish (2005), 304.

- ^ a b c Vryzidis (2010), 283.

- ^ a b Barber (2005), 124.

- ^ a b Barber (2005), 125.

- ^ "Tokyo Drifter". Online Cinematheque. New York City: The Criterion Collection. 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Zoku Tōkyō nagaremono Umiwa Makkana Koinoiro". Nikkatsu. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "続東京流れ者 海は真赤な恋の色". Kinema Junpo. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

References

[edit]- Barber, Stephen (2005). Projected Cities. Clerkenwell: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-127-X. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Berra, John (2010). Directory of World Cinema: Japan. Fishponds: Intellect Publishing. ISBN 9781841503356. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Bleiler, David (2004). TLA Video & DVD Guide: The Discerning Film Lover's Guide. New York City: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-312-31690-9. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Desjardins, Chris (2005). Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-086-2.

- Pratt, Douglas (2005). Doug Pratt's DVD: Movies, Television, Music, Art, Adult, and More!. United States: UNET 2 Corporation. ISBN 1-932916-01-6. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Richie, Donald (2005). A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (Revised and Updated ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2995-9.

- Standish, Isolde (2005). A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film. New York City: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1709-4.

- Vryzidis, Nikolaos (2010). "Tokyo Drifter Critique". Directory of World Cinema: Japan. Fishponds: Intellect Publishing. ISBN 9781841503356. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

External links

[edit]- Tokyo Drifter at IMDb.

- Tokyo Drifter at AllMovie

- Tokyo Drifter at Rotten Tomatoes

- Tokyo Drifter: Catch My Drift an essay by Howard Hampton at the Criterion Collection

- Tokyo Drifter at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese).