Eastern moa

| Eastern moa Temporal range: Pleistocene-Holocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton in Musee des Confluences, Lyon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | †Dinornithiformes |

| Family: | †Emeidae |

| Genus: | †Emeus Reichenbach, 1852 |

| Species: | †E. crassus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Emeus crassus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

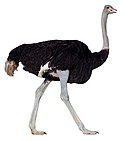

The eastern moa (Emeus crassus) is an extinct species of moa that was endemic to New Zealand.[5][6]

Taxonomy

[edit]When the first specimens were originally described by Richard Owen, they were placed within the genus Dinornis as three different species, but, was later split off into their own genus, Emeus.[7] E. crassus is currently the only species of Emeus, as the other two species, E. casuarinus and E. huttonii are now regarded as synonyms of E. crassus. It has been long suspected that the "species" described as Emeus huttonii and E. crassus were males and females, respectively, of a single species. This has been confirmed by analysis for sex-specific genetic markers of DNA extracted from bone material; the females of E. crassus were 15-25% larger than males.[8] This phenomenon — sexual dimorphism — is not uncommon amongst ratites, being also very pronounced in kiwis.

Description

[edit]

Emeus was of average size, standing 1.5 to 1.8 metres (4.9–5.9 ft) tall, and weighing from 36 to 79kg.[9] Like other moa, it had no vestigial wing bones, hair-like feathers (beige in this case), a long neck and large, powerful legs with very short, strong tarsi.[10] Its tarsometatarsus was restricted in motion to the parasagittal plane, much like most other ratites.[11] It also had a sternum without a keel and a distinctive palate.[10] Emeus had pelvic musculature poorly adapted for cursoriality.[12] Its feet were exceptionally wide compared to other moas, making it a very slow creature. Soft parts of its body, such as tracheal rings (cartilage) or remnants of skin were found, as well as single bones and complete skeletons. As they neared the head, the feathers grew shorter, until they finally turned into coarse hair-like feathers; the head itself was probably bald.[13]

Range and habitat

[edit]

Eastern moa lived only on the South Island, and lived in the lowlands (forests, grasslands, dunelands, and shrublands).[10] During the Last Glacial Maximum, it was confined to a single glacial refugium from which its range expanded during the Holocene.[14] Human colonists (specifically the Māori, who called them "moa mōmona")[1] hunted Emeus into extinction with relative ease. E. crassus was the second most common species found at the Wairau Bar site in Marlborough, where more than 4000 moa were eaten. The species had gone extinct by about 1400.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Emeus crassus. NZTCS". nztcs.org.nz. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Reichenbach, Heinrich Gottlieb Ludwig (1852). Avium systema naturale. Expedition der vollständigsten Naturgeschichte. p. plate XXX.

- ^ Brands, Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Emeus". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 4, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Checklist Committee Ornithological Society of New Zealand (2010). "Checklist-of-Birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands and the Ross Dependency Antarctica" (PDF). Te Papa Press. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Benes, Josef (1979). Prehistoric Animals and Plants. London, UK: Hamlyn. p. 192. ISBN 0-600-30341-1.

- ^ a b Tennyson, Alan J. D. (2006). Extinct birds of New Zealand. Paul Martinson. Wellington, N.Z.: Te Papa Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-909010-21-8. OCLC 80016906.

- ^ Owen, Richard (1846). "Description of Dinornis crassus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1846: 46.

- ^ Huynen, Leon J.; Millar, Craig D.; Scofield, R. P.; Lambert, David M. (2003). "Nuclear DNA sequences detect species limits in ancient moa". Nature. 425 (6954): 175–178. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..175H. doi:10.1038/nature01838. PMID 12968179. S2CID 4413995.(2003)

- ^ Tennyson, Alan; Martinson, Paul (2006-01-01). Extinct Birds of New Zealand. Te Papa Press. ISBN 978-0-909010-21-8.

- ^ a b c Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Moas". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 95–98. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- ^ Zinoviev, Andrei V. (14 March 2015). "Comparative anatomy of the intertarsal joint in extant and fossil birds: inferences for the locomotion of Hesperornis regalis (Hesperornithiformes) and Emeus crassus (Dinornithiformes)". Journal of Ornithology. 156 (S1): 317–323. doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1195-4. ISSN 2193-7192. Retrieved 26 July 2024 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Zinoviev, A. V. (19 December 2013). "Notes on the pelvic musculature of Emeus crassus and Dinornis robustus (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". Paleontological Journal. 47 (11): 1245–1251. Bibcode:2013PalJ...47.1245Z. doi:10.1134/S003103011311018X. ISSN 0031-0301. Retrieved 26 July 2024 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Rawlence, Nj; Wood, Jr; Scofield, Rp; Fraser, C; Tennyson, Ajd (2013). "Soft-tissue specimens from pre-European extinct birds of New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 43 (3): 154–181. Bibcode:2013JRSNZ..43..154R. doi:10.1080/03036758.2012.704878. hdl:10289/7785. S2CID 54024852.

- ^ Verry, Alexander J. F.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Rawlence, Nicolas J. (11 May 2022). "Genetic evidence for post-glacial expansion from a southern refugium in the eastern moa ( Emeus crassus )". Biology Letters. 18 (5). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0013. ISSN 1744-957X. PMC 9091836. PMID 35538842.

External links

[edit]- Eastern Moa. Emeus crassus. by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006