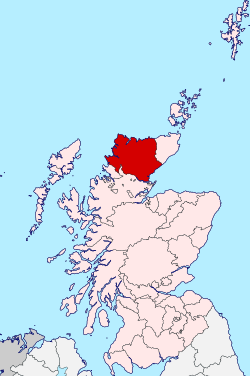

Sutherland

Sutherland

Cataibh (Scottish Gaelic) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 58°15′N 4°30′W / 58.250°N 4.500°W | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Country | |

| Council area | Highland |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,028 sq mi (5,252 km2) |

| Ranked 5th of 34 | |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 12,803 |

| • Density | 6.3/sq mi (2.4/km2) |

| Chapman code | SUT |

Sutherland (Scottish Gaelic: Cataibh) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in the Highlands of Scotland. The name dates from the Viking era when the area was ruled by the Jarl of Orkney; although Sutherland includes some of the northernmost land on the island of Great Britain, it was called Suðrland ("southern land") from the standpoint of Orkney and Caithness.

From the 13th century, Sutherland was a provincial lordship, being an earldom controlled by the Earl of Sutherland. The earldom just covered the south-eastern part of the later county. A shire called Sutherland was created in 1633, covering the earldom of Sutherland and the neighbouring provinces of Assynt to the west and Strathnaver to the north. Shires gradually eclipsed the old provinces in administrative importance, and also become known as counties.

The county is generally rural and sparsely populated. Sutherland was particularly affected by the Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the population has been in decline since the mid-19th century. As at 2011 the population of the county was 12,803, being less than half of the peak of 25,793 which was recorded in 1851. Only one town held burgh status, being Dornoch, where the county's courts were held. Between 1890 and 1975 Sutherland had a county council, which had its main offices in the village of Golspie.

Sutherland has a coast to the east onto the Moray Firth and a coast to the north-west onto the Atlantic Ocean. Much of the county is mountainous, and the western and northern coasts include many high sea cliffs. There are four national scenic areas wholly or partly in the county: Assynt-Coigach, North West Sutherland, Kyle of Tongue and Dornoch Firth, with the first three of these lying along the western and northern coasts.

The county ceased to be used for local government purposes in 1975, when the area became part of the Highland region, which in turn became a single-tier council area in 1996. There was a local government district called Sutherland from 1975 to 1996, which was a lower-tier district within the Highland region, covering a similar but not identical area to the pre-1975 county. The pre-1975 county boundaries are still used for certain functions, being a registration county. The neighbouring counties prior to the 1975 reforms were Caithness to the north-east and Ross and Cromarty to the south.

The Sutherland lieutenancy area was redefined in 1975 to be the local government district. The registration county and the lieutenancy area therefore have slightly different definitions; the registration county does not include Kincardine, but the lieutenancy area does.

History

[edit]In Gaelic, the area is referred to according to its traditional areas: Dùthaich MhicAoidh (or Dùthaich 'IcAoidh) (MacAoidh's country) in the north (also known in English as Mackay Country), Asainte (Assynt) in the west, and Cataibh in the east. Cataibh is also sometimes used to refer to the area as a whole.[a]

Much of the area that would become Sutherland was anciently part of the Pictish kingdom of Cat, which also included Caithness. It was conquered in the 9th century by Sigurd Eysteinsson, Jarl of Orkney. The Jarls owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown. It is possible that Sigurd may have taken Ross to the south as well, but by the time of his death in 892 the southern limit of his territory appears to have been the River Oykel. The Scottish crown claimed the overlordship of the Caithness and Sutherland area from Norway in 1098. The Earls of Orkney thereafter owed allegiance to the Scottish crown for their territory on the mainland, which they held as the Mormaer of Caithness, but owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown for Orkney.[1]

The Diocese of Caithness was established in the 12th century. The bishop's seat was initially at Halkirk, but in the early 13th century was moved to Dornoch Cathedral, which was begun in 1224.[2][3] Around the same time, a new earldom of Sutherland was created from the southern part of the old joint earldom of Orkney and Caithness.[4][5]

In terms of shires (areas where justice was administered by a sheriff), the north of mainland Scotland was all included in the shire of Inverness from the 12th century.[1][6] An act of parliament in 1504 acknowledged that the shire of Inverness was too big for the effective administration of justice, and so declared Ross and Caithness to be separate shires. The boundary used for the shire of Caithness created in 1504 was the diocese of Caithness, which included Sutherland. The Sheriff of Caithness was directed to hold courts at either Dornoch or Wick.[7] That act was set aside for most purposes in 1509, and Caithness (including Sutherland) once more came under the sheriff of Inverness.[8]

In 1633 a new shire called Sutherland was created. It covered the earldom of Sutherland plus the provincial lordships of Strathnaver on the north coast and Assynt on the west coast. Dornoch was declared to be the head burgh of the new shire. The position of Sheriff of Sutherland was a hereditary one, held by the Earls of Sutherland.[9][10]

Over time, Scotland's shires became more significant than the old provinces, with more administrative functions being given to the sheriffs. In 1667 Commissioners of Supply were established for each shire, which would serve as the main administrative body for the area until the creation of county councils in 1890. Following the Acts of Union in 1707, the English term 'county' came to be used interchangeably with the older term 'shire'.[11][12]

Following the Jacobite rising of 1745, the government passed the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746, returning the appointment of sheriffs to the crown in those cases where they had become hereditary positions, as had been the case in Sutherland.[13] From 1748 the government merged the positions of Sheriff of Sutherland and Sheriff of Caithness into a single post. Although they shared a sheriff after 1748, Caithness and Sutherland remained legally separate counties, having their own commissioners of supply and, from 1794, their own lord lieutenants.[14]

The sheriff courts for Sutherland were held at Dornoch Castle until 1850, when they moved to the purpose-built Dornoch Sheriff Court, also known as 'County Buildings', which also served as the meeting place for the Sutherland Commissioners of Supply.[15][16]

Highland Clearances

[edit]

Sutherland, like other parts of the Highlands, was affected by the Highland Clearances, the eviction of tenants from their homes and/or associated farmland in the 18th and 19th centuries century by the landowners. Typically, this was to make way for large sheep farms. The Sutherland Estate (consisting of about two thirds of the county) had the largest scale clearances that occurred in the Highlands, much of this being carried out in 1812, 1814 and 1819–20. In this last period (the largest of the three listed), 1,068 families were evicted: representing an estimated 5,400 people. This population was provided with resettlement in coastal areas, with employment available in fishing or other industries. However, many instead moved to farms in Caithness or left Scotland to emigrate to Canada, the US or Australia.[17] The population has continued to decline since the mid-19th century.[18]

One effect of the clearances was that it concentrated Gaelic speakers in the newly created fishing villages, so extending the survival of the language in these communities. The area on Sutherland's east coast around Golspie, Brora and Embo had its own dialect, East Sutherland Gaelic.[19] This was the last area on the east coast of Scotland where a Gaelic dialect was commonly spoken. Work by the linguist Nancy Dorian from the 1960s onwards studied the gradual decline of East Sutherland Gaelic.[20] The last known native speaker of the dialect died in 2020.[21][22]

County council

[edit]

Elected county councils were established in 1890 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889, taking most of the functions of the commissioners of supply (which were eventually abolished in 1930). The first provisional meeting of the council was held on 13 February 1890 at the County Buildings in Dornoch, but it was decided that a more accessible location was needed for the council's meetings. Although Dornoch was the county's only burgh, it was in the extreme south-eastern corner of the county and lay some seven miles from its then nearest railway station at The Mound.[24] The council's first official meeting was held on 22 May 1890 at Bonar Bridge, and subsequent meetings were generally held in Lairg, with occasional meetings in other places, including Dornoch, Golspie, Brora and Lochinver.[25]

Although the county council generally met in Lairg, from its creation in 1890 the county council's clerk was based in Golspie, and in 1892 the council moved its main administrative offices to a new building on Main Street in Golspie called County Offices, initially sharing the building with the village post office.[26][27][28]

The 1889 Act also led to a review of boundaries, with parish and county boundaries being adjusted to eliminate cases where parishes straddled county boundaries. The parish of Reay had straddled Sutherland and Caithness prior to the act; the county boundary was retained, but the part of Reay parish in Sutherland was transferred to the parish of Farr in 1891.[29]

Since 1975

[edit]

Local government was reformed in 1975 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973, which replaced Scotland's counties, burghs and landward districts with a two-tier structure of upper-tier regions and lower-tier districts. Sutherland became part of the Highland Region. At the district level, most of Sutherland was included in the Sutherland District. The differences between the post-1975 district and the pre-1975 county were that the district excluded the parishes of Farr and Tongue (which both went to the Caithness district), but included the parish of Kincardine from Ross and Cromarty.[30][31][32] The transfer of Farr and Tongue to Caithness district was not popular; less than two years later, in 1977, they were transferred to the Sutherland district, after which the border between the Sutherland and Caithness districts followed the pre-1975 county boundary.[33]

As part of the 1975 reforms, the area served by the Lord Lieutenant of Sutherland was redefined to be the new district, having previously been the county.[34]

Sutherland District Council was based at the former county council's headquarters at the County Offices in Golspie.[35] Throughout the district's existence from 1975 to 1996, a majority of the seats were held by independent councillors.[36]

Further local government reforms in 1996 under the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 saw the regions and districts created in 1975 abolished and replaced with single-tier council areas. The former Highland region became one of the new council areas.[37] The Sutherland lieutenancy area continues to be defined as the area of the pre-1996 district, despite the abolition of the district itself.[38][39] The boundaries of the historic county (as it was following the 1891 boundary changes) are still used for some limited official purposes connected with land registration, being a registration county.[40]

The Highland Council has an area committee called the Sutherland County Committee, comprising the councillors representing the wards which approximately cover the Sutherland area. The council also marks some of the historic county boundaries with road signs.[41]

Geography

[edit]

Much of the population of approximately 13,000 inhabitants are situated in small coastal communities, such as Helmsdale and Lochinver, which until very recently made much of their living from the rich fishing of the waters around the British Isles. Much of Sutherland is poor relative to the rest of the UK, with few job opportunities beyond government-funded employment, agriculture and seasonal tourism. Further education is provided by North Highland College, part of the University of the Highlands and Islands, which has campuses in Dornoch.[42]

The inland landscape is rugged and very sparsely populated. Despite being Scotland's fifth-largest county in terms of area, it has a smaller population than a medium-size Lowland Scottish town. It stretches from the Atlantic in the west, up to the Pentland Firth and across to the North Sea in the east. The west and north coasts have very high sea cliffs and deep sea lochs. The east coast contains the sea lochs of Loch Fleet and Dornoch Firth. Cape Wrath is the most north-westerly point in Scotland. Several peninsulas can be found along the north and west coasts, most notably Strathy Point, A' Mhòine, Durness/Faraid Head (the latter two formed by the Kyle of Durness, Loch Eriboll and the Kyle of Tongue), Ceathramh Garbh (formed by Loch Laxford and Loch Inchard), and Stoer Head. The county has numerous beaches, a remote example being Sandwood Bay, which can only be reached by foot along a rough track.

Sutherland has many rugged mountains such as Ben Hope, the most northerly Munro, and Ben More Assynt, the tallest peak in the county at 998 m (3,274 ft). The western part comprises Torridonian sandstone underlain by Lewisian gneiss. The spectacular scenery has been created by denudation to form isolated sandstone peaks such as Foinaven, Arkle, Cùl Mòr and Suilven. Such mountains are attractive for hill walking and scrambling, despite their remote location. Together with similar peaks to the south in Wester Ross, such as Stac Pollaidh, they have a unique structure with great scope for exploration. On the other hand, care is needed when bad weather occurs owing to their isolation and the risks of injury.

The county contains numerous lochs, some of which have been enlarged to serve as reservoirs. The larger inland lochs are:[b]

- Loch Assynt

- Loch Choire

- Loch Hope

- Loch Loyal

- Loch Meadie

- Loch More

- Loch Naver

- Loch Shin

Owing to its isolation from the rest of the country, Sutherland was reputedly the last haunt of the native wolf, the last survivor being shot in the 18th century. However, other wildlife has survived, including the golden eagle, sea eagle and pine marten amongst other species which are very rare in the rest of the country. There are pockets of the native Scots Pine, remnants of the original Caledonian Forest.

The importance of the county's scenery is recognised by the fact that four of Scotland's forty national scenic areas (NSAs) are located here.[43] The purpose of the NSA designation is to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection from inappropriate development. The areas protected by the designation are considered to represent the type of scenic beauty "popularly associated with Scotland and for which it is renowned".[44] The four NSAs within Sutherland are:

- The Assynt-Coigach NSA has many distinctively shaped mountains, including Quinag, Canisp, Suilven, Cùl Mòr, Stac Pollaidh and Ben More Assynt, that rise steeply from the surrounding "cnoc and lochan" scenery. These can often appear higher than their actual height would indicate due to their steep sides and the contrast with the moorland from which they rise.[45] Assynt lies within Sutherland, whilst Coigach lies within Ross and Cromarty.

- The Dornoch Firth NSA also straddles the boundary between Sutherland and Ross and Cromarty, and covers a variety of landscapes surrounding the narrow and sinuous firth.[45]

- The Kyle of Tongue NSA covers the mountains of Ben Hope and Ben Loyal, as well as woodlands and crofting settlements on the shoreline of the kyle itself.[45]

- The North West Sutherland NSA covers the mountains of Foinaven, Arkle and Ben Stack as well as the coastal scenery surrounding Loch Laxford and Handa Island.[45]

Sutherland includes numerous small islands, generally lying close to the coast of the mainland. None are now inhabited, although some formerly were, notably including Eilean Hoan in Loch Eriboll,[46] Eilean nan Ròn off the north coast near Skerray,[47] and Handa Island in Eddrachillis Bay.[48]

Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 23,117 | — |

| 1811 | 23,629 | +2.2% |

| 1821 | 23,840 | +0.9% |

| 1831 | 25,518 | +7.0% |

| 1841 | 24,782 | −2.9% |

| 1851 | 25,793 | +4.1% |

| 1861 | 24,157 | −6.3% |

| 1871 | 23,298 | −3.6% |

| 1881 | 22,376 | −4.0% |

| 1891 | 21,896 | −2.1% |

| 1901 | 21,440 | −2.1% |

| 1911 | 20,179 | −5.9% |

| 1921 | 17,802 | −11.8% |

| 1931 | 16,101 | −9.6% |

| 1951 | 13,670 | −15.1% |

| 1961 | 13,507 | −1.2% |

| 1971 | 13,055 | −3.3% |

| 2011 | 12,803 | −1.9% |

The parishes which make up the registration county (being the pre-1975 county) had a population of 12,803 at the 2011 census. The Sutherland lieutenancy area (additionally including Kincardine) had a population of 13,451.[49]

The population peaked at just under 26,000 in the 1851 census, but has been in decline since then.[18]

Transport

[edit]

The A9 road main east coast road is challenging north of Helmsdale, particularly at the notorious Berriedale Braes, and there are few inland roads. The Far North Line north-south single-track railway line was extended through Sutherland by the Highland Railway between 1868 and 1871. It enters Sutherland near Invershin and runs along the east coast as far as possible, but an inland diversion was necessary from Helmsdale along the Strath of Kildonan. The line exits to the east of Forsinard.

Helmsdale on the east coast is on the A9 road, at a junction with the A897, and has a railway station on the Far North Line. Buses operate about every two hours Mondays-Saturdays and infrequently on Sundays from Helmsdale to Brora, Golspie, Dornoch, Tain and Inverness in the south, and Berriedale, Dunbeath, Halkirk, Thurso and Scrabster in the north.[50] These are on route X99 and are operated by Stagecoach Group, but tickets can be bought on the Citylink website. Various other Stagecoach buses link the other towns of eastern Sutherland, such as Lairg and Bonar Bridge to Tain and Inverness.[51] The western areas of the county are less well served by public transport, however the Far North Bus company does provided scheduled services connecting Durness to Lairg (bus 806), and from Durness to Thurso via the towns of the north Sutherland coast (bus 803).[52]

There are no commercial airports in the county. There is a small general aviation airstrip south of Dornoch, the former RAF Dornoch, which sees little traffic.[53]

Civil parishes

[edit]

Parishes existed from medieval times. From 1845 to 1894 they had parish boards and from 1894 to 1930 they had parish councils. They have had no administrative functions since 1930, but continue to be used for the presentation of statistics.[54]

Following the 1891 parish boundary changes, Sutherland contained the following civil parishes:[31][55]

Eddrachillis and Tongue were formerly part of Durness parish, being separated in 1724.[56] The other eleven parishes are ancient in origin.

Community councils

[edit]Community councils were created in 1975 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. They have no statutory powers, but serve as a representative body for their communities. The Highland Council designates community council areas, but a community council is only formed if there is sufficient interest from the residents. Following a review in 2019, Sutherland comprised the following communities, all of which have community councils as at 2024:[57][58]

Settlements

[edit]- Achriesgill

- Altnaharra

- Armadale

- Assynt

- Bettyhill

- Bonar Bridge

- Brora

- Clashmore

- Creich

- Dornoch

- Drumbeg

- Durness

- Embo

- Evelix

- Golspie

- Helmsdale

- Inchnadamph

- Invershin

- Kildonan

- Kinbrace

- Kinlochbervie

- Lairg

- Lochinver

- Melvich

- Portgower

- Portskerra

- Pulrossie

- Rogart

- Rosehall

- Scourie

- Skerray

- Stoer

- Strathy

- Tongue

Constituency

[edit]The Sutherland constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom represented the county from 1708 to 1918. The constituency excluded the burgh of Dornoch, which was represented as a component of the Northern Burghs constituency. In 1918 the Sutherland constituency and Dornoch were merged into the then new constituency of Caithness and Sutherland. In 1997 Caithness and Sutherland was merged into Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross.

The Scottish Parliament constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross was created in 1999 for the newly established parliament. The constituency was extended for the 2011 election to include more of Ross-shire, and was so renamed Caithness, Sutherland and Ross. In the Scottish Parliament, Sutherland is represented also as part of the Highlands and Islands electoral region.

Flag

[edit]In 2018 a flag was adopted for Sutherland, following a competition organised by the Lord Lieutenant of Sutherland. The winning design has black lines on a white background, arranged as an overlapping saltire and Nordic cross, representing combined Scottish and Norwegian heritage. A gold star representing the sun is formed where the lines intersect.[59]

Sutherland in popular culture

[edit]In M. C. Beaton's Hamish Macbeth mystery series, the fictional towns of Lochdubh and Strathbane are located in Sutherland.

Rosamunde Pilcher's last novel Winter Solstice is largely set in and around the fictional Sutherland town of Creagan, located in the Sutherland town of Dornoch.

The ship captained by Horatio Hornblower in C. S. Forester’s book A Ship of the Line is called HMS Sutherland.

The short story "Monarch of the Glen" by Neil Gaiman is set in Sutherland, and includes a discussion on the origin of the name.

It is still common to refer to the entire Gaelic-speaking world with the phrase "Ó Chataibh go Cléire" (from Sutherland to Cape Clear) or "Ó Chataibh go Ciarraí" (from Sutherland to Kerry). Cléire and Ciarraí are Gaelic-speaking regions in the far south-west of Ireland.

Notable people with Sutherland connections

[edit]- George Mackay Brown (1921–1996), "Bard of Orkney", whose mother was born in Strathy

- John Lennon (1940–1980), a frequent visitor to Durness

- Norman MacCaig (1910–1996), Edinburgh-born poet, who wrote about the region of Assynt, which he visited many times over a period of forty years.

- Patrick Sellar (1780–1851), lawyer and factor

- W. C. Sellar (1898–1951), humourist who wrote for Punch, best known for the book 1066 and All That

- William Young Sellar (1825–1890), classical scholar

- Joe Strummer (1952–2002), frontman of the Clash; born John Graham Mellor in Ankara, Turkey; his mother, Anna Mackenzie, was a crofter's daughter born and raised in Bonar Bridge

- Donald Ross (1872–1948), golfer and golf course designer, born in Dornoch. Ross's most famous designs are Pinehurst No. 2, Aronimink Golf Club, East Lake Golf Club, Seminole Golf Club, Oak Hill Country Club, Glen View Club, Memphis Country Club, Inverness Club, Miami Biltmore Golf Course and Oakland Hills Country Club; all in the United States of America.

See also

[edit]- Clan Sutherland

- List of counties of Scotland 1890–1975

- Medieval Diocese of Caithness

- Politics of the Highland council area

- Subdivisions of Scotland

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Grant, Alexander (2000). "The Province of Ross and the Kingdom of Alba". In Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R. Andrew (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 98–110. ISBN 1 86232 151 5. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Dornoch Cathedral (LB24632)". Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Farmer, David Hugh (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 0-19-280058-2.

- ^ Fraser, William (1892). The Sutherland Book. Edinburgh. p. 1. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pulsiano, Phillip, ed. (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia. New York and London: Garland Publishing. pp. 63–65. ISBN 0824047877. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Alice (2016). The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland, 1124–1290. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 144, 234–235. ISBN 9780198749202. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Legislation: final legislation published outwith the parliamentary register, Edinburgh, 11 March 1504". The Records of the Parliament of Scotland to 1707. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Legislation, 8 May 1509". The Records of the Parliament of Scotland to 1707. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Act in favour of John Gordon, Earl of Sutherland, 28 June 1633". The Records of the Parliament of Scotland to 1707. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Chamberlayne, John (1748). Magnae Britanniae Notita: or, the Present State of Great Britain. London. p. 314. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Act of the convention of estates of the kingdom of Scotland etc. for a new and voluntary offer to his majesty of £72,000 monthly for the space of twelve months, 23 January 1667". Records of the Parliament of Scotland. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Scottish Counties and Parishes: their history and boundaries on maps". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Whetstone, Ann E. (1977). "The Reform of the Scottish Sheriffdoms in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 9 (1): 61–71. doi:10.2307/4048219. JSTOR 4048219.

- ^ Sheriffs (Scotland) Act 1747

- ^ "Dornoch Castle A Brief History" (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Former Dornoch County Buildings and Court House, Castle Street, Dornoch (Category B Listed Building) (LB24637)". Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ Richards, Eric (2000). The Highland Clearances People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil (2013 ed.). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-78027-165-1.

- ^ a b "Sutherland Scottish County". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Dorian, Nancy C. (2010). Investigating Variation: The effects of social organization and social setting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 40–42. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ [1] Archived 18 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wilma Ros, Eurabol, air bàsachadh". BBC Naidheachdan. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ "ROSS". Northern Times. 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Urquhart, Robert Mackenzie (1973). Scottish Burgh and County History (PDF). p. 59. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Sutherland County Council". Highland News. Inverness. 15 February 1890. p. 3. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Sutherland County Council". Inverness Courier. 23 May 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Notes from Golspie". Northern Ensign. Wick. 13 December 1892. p. 3. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "No. 18541". The Edinburgh Gazette. 3 March 1967. p. 179.

- ^ "Main Street". Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Shennan, Hay (1892). Boundaries of counties and parishes in Scotland as settled by the Boundary Commissioners under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. Edinburgh: W. Green. p. 130. Retrieved 10 September 2024.

- ^ "Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1973 c. 65, retrieved 17 April 2023

- ^ a b "Quarter-inch Administrative Areas Maps: Scotland, Sheet 3, 1968". National Library of Scotland. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "No. 14590". The Edinburgh Gazette. 11 October 1929. p. 1188.

- ^ "The Caithness and Sutherland Districts (Tongue and Farr) Boundaries Order 1977", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1977/14, retrieved 1 August 2024

- ^ "The Lord-Lieutenants Order 1975", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1975/428, retrieved 1 September 2024

- ^ "No. 23939". The Edinburgh Gazette. 20 February 1996. p. 397.

- ^ "Compositions calculator". The Elections Centre. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ "Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1994 c. 39, retrieved 17 April 2023

- ^ "The Lord-Lieutenants (Scotland) Order 1996", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1996/731, retrieved 1 September 2024

- ^ "Lord-Lieutenant of Sutherland". Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Land Mass Coverage Report" (PDF). Registers of Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Sutherland County Committee". The Highland Council. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Centre for History - University of the Highlands and Islands". www.uhi.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Map: National Scenic Areas of Scotland" (PDF). Scottish Government. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Countryside and Landscape in Scotland - National Scenic Areas". Scottish Government. 4 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d "The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Eilean Hoan". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Eilean Nan Ron". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Handa Island". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "2011 census table data: Civil Parish 1930". Scotland's Census. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Stagecoach North Scotland - Caithness and Sutherland Area Guide from 20 August 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stagecoach North Scotland - Black Isle and Easter Ross Travel Guide from 07 January 2019" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Durness Bus". Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Dornoch". Abandoned Forgotten & Little Known Airfields in Europe. www.forgottenairfields.com. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Civil Parishes". National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Old Roads of Scotland". Old Roads of Scotland. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ GENUKI. "Genuki: Durness, Sutherland". www.genuki.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Community Councils in the Highland Council area". The Highland Council. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Scheme review 2018/2019". The Highland Council. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ McMorran, Caroline (21 December 2018). "County's flag finally flying but public opinion still split". Northern Times. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Cataibh can be read as meaning among the Cats and the Cat element appears as Cait in Caithness. The Scottish Gaelic name for Caithness, however, is Gallaibh, meaning among the Strangers (i.e. the Norse who extensively settled there).

- ^ Being the lochs (excluding sea lochs) shown on modern Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 maps labelled in all capital letters.

- ^ Ardgay and District (corresponding to the historic parish of Kincardine) is in the Sutherland lieutenancy area, but is not within the registration county or historic county of Sutherland, having been part of Ross and Cromarty prior to 1975.

Bibliography

[edit]- Omand, Donald (1991). The Sutherland Book. Golspie, Scotland, UK: The Northern Times Limited. ISBN 1-873610-00-9.

External links

[edit]- Map of Sutherland on Wikishire

- "Small Area Population Estimates 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. (412 KB) (www.highland.gov.uk)

- Miss Dempster "Folk-Lore of Sutherlandshire" Folk-Lore Journal. Volume 6, 1888.