Suryavarman II

| Suryavarman II | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| King of the Khmer Empire | |||||||||

| Reign | 1113–1150 CE | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Dharanindravarman I | ||||||||

| Successor | Dharanindravarman II | ||||||||

| Born | 11th century CE (1094 or 1098[1]) Angkor, Khmer Empire (now in Siem Reap, Cambodia) | ||||||||

| Died | 1150 CE [2][3] Angkor, Khmer Empire (now in Siem Reap, Cambodia) | ||||||||

| Burial | Angkor Wat, Siem Reap, Cambodia | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Father | Ksitindraditya | ||||||||

| Mother | Narendralakshmi | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism (Vaishnavism) | ||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||

Suryavarman II (Khmer: សូរ្យវរ្ម័នទី២, UNGEGN: Soryôvôrmoăn Ti 2, ALA-LC: Sūryavarmăn Dī 2), posthumously named Paramavishnuloka, was the ruler of the Khmer Empire from 1113 until his death in 1150.[4] He is most famously known as the builder of Angkor Wat, the largest Hindu temple in the world, which he dedicated to Vishnu. His reign's monumental architecture, numerous military campaigns and restoration of strong government have led historians to rank Suryavarman II as one of the empire's greatest rulers.

Early years

[edit]Suryavarman appears to have grown up in a provincial estate in 1094 or 1098,[1] at a time of weakening central control in the empire. An inscription lists his father as Ksitindraditya and his mother as Narendralakshmi. As a young prince, he maneuvered for power, contending he had a legitimate claim to the throne. “At the end of his studies,” states an inscription, “he approved the desire of the royal dignity of his family.” He appears to have dealt with a rival claimant from the line of Harshavarman III, probably Nripatindravarman, who held sway in the south, then to have turned on the elderly and largely ineffectual king Dharanindravarman I, his great uncle. “Leaving on the field of combat the ocean of his armies, he delivered a terrible battle,” states an inscription. “Bounding on the head of the elephant of the enemy king, he killed him, as Garuda on the edge of a mountain would kill a serpent.”[5] Scholars have disagreed on whether this language refers to the death of the southern claimant or of King Dharanindravarman. Suryavarman II also sent a mission to the Chola dynasty of south India and presented a precious stone to the Chola Emperor Kulothunga Chola I in 1114 CE.[6]

Suryavarman was enthroned in 1113 AD.[7]: 159 An aged Brahmin sage named Divakarapandita oversaw the ceremonies, this being the third time the priest had officiated a coronation. Inscriptions record that the new monarch studied sacred rituals, celebrated religious festivals and gave gifts to the priest such as palanquins, fans, crowns, buckets and rings. The priest embarked on a lengthy tour of temples in the empire, including the mountaintop Preah Vihear, which he provided with a golden statue of dancing Shiva.[8] The king’s formal coronation took place in 1119 AD, with Divakarapandita again performing the rites.

The first two syllables in the monarch's name are a Sanskrit language root meaning "sun". Varman is the traditional suffix of the Pallava dynasty that is generally translated as "shield" or "protector", and was adopted by Khmer royal lineages.

Life and reign

[edit]Dvaravati began to come under the influence of the Khmer Empire and central-southeast Asia was ultimately invaded by King Suryavarman II in the first half of the 12th century.

During his decades in power, the king reunited the empire. Vassals paid him tribute. He staged large military operations in the east against the Chams, but these were largely unsuccessful.[9]: 113–114 Inscriptions in the neighboring Indianized state of Champa and accounts left by writers in Đại Việt (Dai Viet), a Vietnamese precursor state, say that Suryavarman II staged 3 major but unsuccessful attacks in Nghệ An province and Quảng Bình province, sometimes with the support of Champa. In 1128, he is said to have led 20,000 soldiers against Dai Viet, but was defeated and chased out. The next year he sent a fleet of more than 700 vessels to attack its coast. In 1132, combined Khmer and Cham forces again invaded Dai Viet, with a final attempt in 1137, to no real success.[10] Later, the Cham king Jaya Indravarman III made peace with Lý king of Dai Viet and refused to support further attacks. In 1145 AD, Suryavarman II appears to have invaded Champa, defeated its king Jaya Indravarman III, and sacked the capital Vijaya with the help of Kulothunga Chola II.[11]: 75–76 On the Cham throne he placed a new king, Harideva, said to be the younger brother of the Khmer ruler's wife. In subsequent fighting, Cham forces under Jaya Harivarman I recaptured the capital and killed Harideva.[12] A final expedition in 1150 ended in a disastrous withdrawal.[7]: 159–160

According to Vietnamese history books, Khmer planned to invade Dai Viet one more time in 1150. But while Khmer troops gathered in Nghe An (in southern Dai Viet), they faced widespread diseases and pandemics, and so retreated just before the invasion.[13]

In addition to war, Suryavarman practiced diplomacy, resuming formal relations with China in 1116 AD. A Chinese account of the 13th century says that the Khmer embassy had 14 members, who after reaching Chinese soil were given special court garments. “Scarcely have we arrived to contemplate anear your glory than we are already filled with your benefits,” one of the ambassadors is quoted as telling the Chinese emperor. The embassy went home the following year. Another embassy visited in 1120; in 1128, the emperor conferred high dignities on the Khmer ruler, deeming him “great vassal of the empire.” Problems concerning commerce between the two states were examined and regulated.[7]: 159, 162 [14]

The king's reign saw great innovations in art and architecture and it is believed that the sudden change was due to the presence of Cholas. He presided over the construction of Angkor Wat,[15]: 372, 378–379 the largest temple ever built in the capital, and in many modern minds the ultimate masterpiece of Khmer architecture. Its five central towers evoke the peaks of Mount Meru, home of the Hindu gods. It was resplendent with more than 1,860 carved apsara, or heavenly nymphs, and hundreds of meters of elaborate bas-reliefs depicting the Hindu legends and scenes from contemporary life. Other temples dating to his reign include Banteay Samre, Thommanon, Chau Say Tevoda, Wat Athvea and, east of the capital, the huge Beng Mealea complex.

Suryavarman married, but no record exists of his wives' names. Suryavarman II was unusual among Khmer kings in making Vishnu rather than Shiva the focus of court religious life. The reasons for this decision are not known. Scholars have long debated whether his association with Vishnu helps explain why Angkor Wat faces west, the cardinal direction with which Vishnu is associated, rather than east, the more common orientation for Khmer temples.

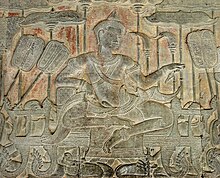

Suryavarman II was the first Khmer king to be depicted in art. A bas-relief in the south gallery of Angkor Wat shows him seated on an elaborate wooden dais whose legs and railings are carved to resemble naga snakes. On his head is a pointed diadem, and his ears have pendants. He wears anklets, armlets and bracelets. His right hand holds what seems to be a small dead snake; the meaning of this is unclear. His torso curves gracefully, his legs folded beneath him. The general image projected is one of serenity, and comfort with power and position.

His image is part of a unique and detailed portrait of court life in the Angkor period. The scene's setting appears to be outside, amidst a forest. Kneeling attendants hold over His Majesty a profusion of fans, fly whisks and parasols that denoted rank. Princesses are carried in elaborately carved palanquins. Whiskered Brahman priests look on, some of them apparently preparing things for a ceremony. To the right of His Majesty, a courtier kneels, apparently presenting something. Advisers look on, kneeling, some with hands over hearts in a gesture of obeisance. To the right we see an elaborate procession, with retainers sounding conches, drums and a gong. An ark bearing the royal fire, symbol of power, is carried on his shoulders.

Further on in the gallery is a display of Suryavarman's military might. Commanders with armor and weapons stand atop fierce war elephants, with ranks of foot soldiers below, each holding a spear and shield. One of the commanders is the king himself, looking over his right shoulder, his chest covered with armour, a sharp weapon in his right hand.

Death and succession

[edit]Inscriptional evidence suggests that Suryavarman II died between 1150, possibly during a military campaign against Champa;[2] before that, his troops were defeated by Vietnamese troops led by Tô Hiến Thành. Some sources said he died around 1150 in Angkor due to the fact that the records of Suryavarman II stopped around that year.[16][1] He was succeeded by his cousin Dharanindravarman II. A period of weak rule and feuding began.[9]: 120

Suryavarman was given the posthumous name Paramavishnuloka, "He Who Has Entered the Heavenly World of Vishnu". Angkor Wat appears to have been completed only after his death.[9]: 118

A modern sculpture that adapts his court image in the Angkor Wat bas-reliefs today greets visitors arriving at the Siem Reap airport. Parasols shelter this image of the king, as they did the real Suryavarman almost nine centuries ago.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Del Testa, David W. (2014). "Suryavarman II". Government Leaders, Military Rulers and Political Activists. p. 178. doi:10.4324/9781315063706-177. ISBN 978-1-315-06370-6.

- ^ a b "Suryavarman II | Biography & Facts | Britannica".

- ^ Study and Teaching Guide: The History of the Renaissance World: A curriculum guide to accompany the History of the Renaissance World. Peace Hill Press. 22 November 2016. ISBN 978-1-945841-01-9.

- ^ "Suryavarman II | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Briggs, "The Ancient Khmer Empire," p. 187.

- ^ A History of India Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund: p.125

- ^ a b c Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ Higham, "The Civilization of Angkor," p. 113.

- ^ a b c Higham, C., 2001, The Civilization of Angkor, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 9781842125847

- ^ "Thánh Tông Hoàng Đế" [Emperor Thanh Tong]. www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de (in Vietnamese).

- ^ Maspero, G., 2002, The Champa Kingdom, Bangkok: White Lotus Co., Ltd., ISBN 9747534991

- ^ Briggs, "The Ancient Khmer Empire," p. 192.

- ^ "Anh Tông Hoàng Đế" [Emperor Anh Tong]. www.informatik.uni-leipzig.de (in Vietnamese).

- ^ Briggs, "The Ancient Khmer Empire," p. 189.

- ^ Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 9786167339443

- ^ Kaziewicz, Julia (22 November 2016). Study and Teaching Guide: The History of the Renaissance World: A curriculum guide to accompany The History of the Renaissance World. Peace Hill Press. ISBN 978-1-945841-01-9.

References

[edit]- Briggs, Lawrence Palmer. The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 41, Part 1. 1951

- Vickery, Michael, The Reign of Suryavarman I and Royal Factionalism at Angkor. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 16 (1985) 2: 226-244.