Ligature (medicine)

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (February 2022) |  |

In surgery or medical procedure, a ligature consists of a piece of thread (suture) tied around an anatomical structure, usually a blood vessel, another hollow structure (e.g. urethra) or an accessory skin tag to shut it off.

History

[edit]The principle of ligation is attributed to Hippocrates and Galen.[1][2] In ancient Rome, ligatures were used to treat hemorrhoids.[3] Spanish Muslim doctor Al-Zahrawi described the procedure around the year 1000 in his book Kitab al-Tasrif.[4] The concept of a ligature was reintroduced some 500 years later by Ambroise Paré and first performed by him in the village of Damvillers.[5][6] It finally found its modern use in 1870–1880, made popular by Jules-Émile Péan.

Procedure

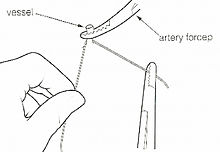

[edit]With a blood vessel the surgeon will clamp the vessel perpendicular to the axis of the artery or vein with a hemostat, then secure it by ligating it; i.e. using a piece of suture around it before dividing the structure and releasing the hemostat. It is different from a tourniquet in that the tourniquet will not be secured by knots and it can therefore be released/tightened at will.

Ligation is one of the remedies to treat skin tag, or acrochorda. It is done by tying string or dental floss around the acrochordon to cut off the blood circulation.[7] Home remedies include commercial ligation bands that can be placed around the base of skin tags.[8]

Complications of ligation in polydactyly treatment include infection, neuroma or cyst formation.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lois N. Magner (1992). A History of Medicine. CRC Press. p. 91.

- ^ Greenblatt, Samuel; Dagi, T.; Epstein, Mel (1997-01-01). A History of Neurosurgery: In its Scientific and Professional Contexts. Thieme. p. 203. ISBN 9781879284173. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Khubchandani, Indru T.; Paonessa, Nina (2002-01-11). Surgical Treatment of Haemorrhoids. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-85233-496-3.

- ^ Cosman, Madeleine Pelner; Jones, Linda Gale (2008). Handbook to life in the medieval world. 3: Handbook to life in the medieval world / Madeleine Pelner Cosman and Linda Gale Jones. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4887-8.

- ^ Paget, Stephen (1897). Ambroise Paré and his times, 1510-1590. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 23. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Joseph Albert Massard. "Damvillers, Mansfeld and Son: Ambroise Paré, the Father of Surgery, and Luxembourg." Lëtzebuerger Journal, vol. 60, no. 74, 17 April 2007, pp. 11–12. online. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Cutaneous skin tag". Medline Plus. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ MHS, Kristina Liu, MD (March 23, 2020). "Skin tag removal: Optional but effective". Harvard Health.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnes, Curtis J.; De Cicco, Franco L. (2022). "Supernumerary Digit". Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 33232075.