Lunate sulcus

| Lunate sulcus | |

|---|---|

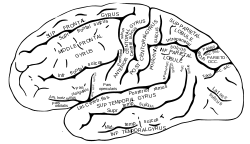

Lateral surface of left cerebral hemisphere, viewed from the side. | |

| Details | |

| Location | Occipital lobe |

| Function | Sulcus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sulcus lunatus |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_4017 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.134 |

| TA2 | 5483 |

| FMA | 83788 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In brain anatomy, the lunate sulcus or simian sulcus, also known as the sulcus lunatus, is a fissure in the occipital lobe[1] variably found in humans and more often larger when present in apes and monkeys.[2] The lunate sulcus marks the transition between V1 and V2, the primary and secondary visual cortices.[3]

The lunate sulcus lies further back in the human brain than in the chimpanzee's.[4] The evolutionary expansion in humans of the areas in front of the lunate sulcus would have caused a shift in the location of the fissure.[4][5] Evolutionary pressures may have resulted in the human brain undergoing internal reorganization to develop the capability of language.[6] It has been speculated that this reorganization is implemented during early maturity and is responsible for eidetic imagery in some adolescents.[6]

During early development, the neural connections in the prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal lobe rapidly expand to allow capability for human language, while visual memory capacity of human brain would become limited.[7] Biological studies have demonstrated that the lunate sulcus is subject to white matter growth, and dental fossil and tomography studies have shown that the brain organization of Australopithecus africanus is pongid-like.[8]

History

[edit]

The lunate sulcus was first identified during the early 1900s in the human brain as a homologue of the Affenspalte, a major sulcus defining the primary visual cortex (V1) in apes and other monkey species, by anatomist and Egyptologist Grafton Elliot Smith.[9] Based on Smith’s observations from studying over 400 Egyptian human and ape brains, he believed that the sulcal patterns between humans and apes were similar.[9] His methodology involved mapping cortical areas via simple visual inspection of endocasts from mummies, as well as fresh whole and sectioned brains.[9] Paleoneurologists study endocasts to gather information about brain size and shape, as well as sulcal patterns resulting from pressure-induced impressions by the brain’s surface. Comparison of data gathered from endocasts and the brains of living hominoids allows scientists to study the evolution of the human brain, both anatomically and cognitively. Ultimately, Smith argued that the lunate sulcus was responsible for delineating the rostrolateral boundary of the V1 in both humans and non-human primates, and he placed the lunate sulcus in chimpanzee more rostral than that in human.[9] Based on this observation, he was the first to hypothesize that the caudal shift of the lunate sulcus in Homo sapiens was due to the evolutionary rapid overgrowth of the cerebral cortex that is unique to human neurodevelopment.[9]

Smith’s observation that the caudal shift of the lunate sulcus could also be used as a predictor for determining both the evolutionary posterolateral shift of the occipital lobes/V1 and the corresponding expansion of the neighboring parietotemporo-occipital visual association cortices was supported by recent research.[9][10] However, some neuroanatomists today disagree with Smith’s assertion that a lunate sulcus exists in humans, arguing that there is only an Affenspalte which is unique to apes. Specifically, in a high-resolution MRI study conducted by Allen et al. (2006), the researchers scanned and analyzed 220 human brains and found no sign of the lunate sulcus homologue. Based on this finding, they suggested that the claim asserting humans have a lunate sulcus homologue fails to account for and show appreciation of the extensive evolutionary reorganization of the visual cortex in humans.[1]

Evolution

[edit]Analyzing variability in the location of gross anatomical landmarks such as sulci is an accepted method for studying evolutionary hominin brain reorganization. The position of the lunate sulcus in the occipital lobe has been studied in humans, early hominin endocasts, apes, and monkeys by researchers seeking to make inferences about the morphological evolution of brain regions associated with human visual versus cognitive behaviors.[10][11] However, some scientists remain skeptical about whether the lunate sulcus is a valid and reliable indicator for studying volumetric changes in the V1 due to the inconsistencies of the sulcus’s presence and lack of histological correspondence with cytoarchitectonic boundaries in hominoids.[12] Despite this, previous allometry studies have suggested that the lunate sulcus shifts from a lateral-anterior to a medial-posterior position as brain size increases.[13][14] Such shifts have been credited with predicting whether the lunate sulcus will occur or not based on an increase or reduction in V1 volume, thus providing an explanation for inconsistencies in its presence and position in the occipital lobes.[13][15] Moreover, a study conducted by de Sousa et al. (2010) compared the volumes of the V1 relative to the position of the lunate sulcus in three-dimensional reconstructed non-human hominoid brains to determine if an allometric relationship existed between V1 volume and lunate sulcus position. The researchers found that the position of the lunate sulcus does accurately predict V1 volume in apes, and that V1 volume in humans is smaller than would be expected based on our large brain size.[10] Furthermore, other research suggests a more posteriorly positioned lunate sulcus from the early hominin fossil record.[4][5] Based on all these findings, de Sousa et al. (2010) concluded V1 reduction began during early hominin evolution, given the more lateral-anterior position of the lunate sulcus in human and other primate brains today.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Allen JS, Bruss J, Damasio H (August 2006). "Looking for the lunate sulcus: a magnetic resonance imaging study in modern humans". Anat Rec A. 288 (8): 867–76. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20362. PMID 16835937.

- ^ Srijit D, Shipra P (2008). "Unilateral absence of the lunate sulcus: an anatomical perspective". Rom J Morphol Embryol. 49 (2): 257–8. PMID 18516336.

- ^ Schmolesky, M. "The organization of the retina and visual system".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Rincon, Paul (2004). "Human brain began evolving early". BBC.

- ^ a b Bruner, E (2014). Human paleoneurology. Springer.

- ^ a b Ko, Kwang Hyun (2015). "Brain Reorganization Allowed for the Development of Human Language: Lunate Sulcus". International Journal of Biology. 7 (3): 59. doi:10.5539/ijb.v7n3p59.

- ^ Gogtay, N (2004). "Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (21): 8174–8179. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402680101. PMC 419576. PMID 15148381.

- ^ Dean, C (2001). "Growth processes in teeth distinguish modern humans from Homo erectus and earlier hominins". Nature. 414 (6864): 628–631. Bibcode:2001Natur.414..628D. doi:10.1038/414628a. PMID 11740557. S2CID 4428635.

- ^ a b c d e f g Falk, Dean (May 2014). "Interpreting sulci on hominin endocasts: old hypothesis and new findings". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8: 134. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00134. PMC 4013485. PMID 24822043.

- ^ a b c De Sousa, Alexandra A.; Sherwood, Chet C.; Mohlberg, Hartmut; Amunts, Katrin; Schleicher, Axel; MacLeod, Carol E.; Hof, Patrick R.; Frahm, Heiko; Zilles, Karl (April 2010). "Hominoid visual brain structure volumes and the position of the lunate sulcus". Journal of Human Evolution. 58 (4): 281–292. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.11.011. PMID 20172590.

- ^ Holloway L, Broadfield C, Yuan S, Tobias V (2003). "The lunate sulcus and early hominid brain evolution: Toward the end of a controversy". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 120: 117. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10249.

- ^ Amunts K, Schleicher A, Zilles K (2007b). "Cytoarchitecture of the cerebral cortex: More than localization". NeuroImage. 37 (4): 1061–5, discussion 1066–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.037. PMID 17870622. S2CID 3359887.

- ^ a b Jerison J (1975). "Fossil evidence of evolution of the human brain". Annual Review of Anthropology. 4: 27–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.04.100175.000331.

- ^ Kaas, JH (2000). "Why is brain size so important: design problems and solutions as neocortex gets bigger or smaller". Brain and Mind. 1: 7–23. doi:10.1023/A:1010028405318. S2CID 142597701.

- ^ Preuss M and Coleman Q (2002). "Human-specific organization of primary visual cortex: Alternating compartments of dense Cat-301 and calbindin immunore- activity in layer 4A". Cerebral Cortex. 12 (7): 671–691. doi:10.1093/cercor/12.7.671. PMID 12050080.