Stutz Motor Car Company

| |

| Company type | Public company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Automotive |

| Founded | Indianapolis, Indiana, United States (1911) |

| Founder |

|

| Defunct | 1939 |

| Headquarters | , United States |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | Sports cars, Luxury cars |

The Stutz Motor Car Company was an American automobile manufacturer based in Indianapolis, Indiana that produced high-end sports and luxury cars. The company was founded in 1911 as the Ideal Motor Car Company before merging with the Stutz Auto Parts Company in 1913. Due to the pressures of the Great Depression, the Stutz company went defunct in 1938. The Stutz Motor Car Company produced roughly 39,000 automobiles in their Indianapolis factory during their existence.[1]

The Stutz brand was revived in 1968 as Stutz Motor Car of America, with a focus on producing Neoclassic automobiles. The company is still in existence, but sales of factory-produced vehicles ceased in 1995.

History

[edit]The Ideal Motor Car Company, organized in June 1911 by Harry C. Stutz with his friend, Henry F Campbell, began building Stutz cars in Indianapolis in 1911.[2] They set this business up after a car built by Stutz in under five weeks and entered in the name of his Stutz Auto Parts Co. was placed 11th in the Indianapolis 500 earning it the slogan "the car that made good in a day". Ideal built what amounted to copies of the racecar with added fenders and lights and sold them with the model name Stutz Bearcat, Bear Cat being the name of the actual racecar.

-

Harry Stutz

-

Henry Campbell

-

Bear Cat with designer, driver, and riding mechanic 1911

-

1914 production Stutz Bearcat

The Bearcat featured a 389 cu in (6.4 L) Wisconsin brawny four-cylinder T-head engine with four valves per cylinder,[citation needed] one of the earliest multi-valve engines, matched with one of Harry Stutz's transaxles. Stutz Motor has also been credited with the development of "the underslung chassis,"[citation needed] an invention that greatly enhanced the safety and cornering of motor vehicles and one that is still in use today. Stutz's "White Squadron" race team won the 1913 and 1915 national championships before withdrawing from racing in October 1915.

Stutz Motor Car Company of America

[edit]In June 1913 Ideal Motor Car Company changed its name to Stutz Motor Car Company (of Indiana) and Stutz Auto Parts Company (it manufactured Stutz's transaxle) was merged into it. To find new investment capital for expansion Stutz Motor Car Company (of Indiana) was sold in 1916 to Stutz Motor Car Company of America under an agreement with a consortium to list the specially organized holding company's stock on the New York Stock Exchange. As a part of the listing process, the number of cars produced and sold since 1912 was reported to potential investors: 1913, 759; 1914, 649; 1915, 1,079; 1916 (first six months) 874. Stutz, Campbell, Allan A. Ryan, and four others were directors. Stutz was president and Allan A. Ryan vice-president.[2]

Harry Stutz left Stutz Motor on July 1, 1919, and together with Henry Campbell established the H. C. S. Motor Car Company and Stutz Fire Apparatus Company.

Allan Aloysius Ryan (1880–1940), father of Allan A. Ryan Jr., was left in control of Stutz Motor. Ryan Sr., and friends attempted stock manipulation which in April 1920 proved disastrous. Stutz Motor was delisted. The Stutz Motor corner was the last publicly detected intentional corner on the New York Stock Exchange. Ryan Sr., was bankrupt in August 1922 as well as disinherited by his father, Thomas Fortune Ryan. Meanwhile, two friends of Thomas Fortune Ryan found themselves with large parcels of Stutz stock, Charles Michael Schwab and Eugene Van Rensselaer Thayer Jr. (1881–1937), president of Chase National Bank.[3]

The new owners brought in Frederick Ewan Moskowics, formerly of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, Marmon, and Franklin, in 1923. Moskowics quickly refocused the company as a developer of safety cars, a recurring theme in the auto industry. In the case of Stutz, the car featured safety glass, a low center of gravity for better handling, and a hill-holding transmission called "Noback". A significant advance was the 1931 DOHC 32-valve in-line 8 called the "DV32" (DV for 'dual valve'). This was during the so-called "cylinders race" of the early 1930s when makers of some expensive cars were rushing to produce multi-cylinder engines. However, Stutz continued its performance heritage with the dual overhead cam, in-line 8 engine design. Brochures boasted the cars were capable of top speeds of more than 100 mph (160 km/h).

The following year, a 4.9-liter (300 in3) Stutz (entered and owned by wealthy French pilot and inventor Charles Weymann[4]) in the hands of by Robert Bloch and Edouard Brisson finished second at the 24 Hours of Le Mans (losing to the 4.5-liter [270 in3] Bentley of Rubin and Barnato,[5] despite losing top gear 90 minutes from the flag[6]), the best result for an American car until 1966. That same year, development engineer and racing driver Frank Lockhart used a pair of supercharged 91-cubic-inch (1.49 L) DOHC engines in his Stutz Black Hawk Special streamliner land speed record car,[7] while Stutz set another speed record at Daytona Beach, reaching 106.53 mph (171.44 km/h) driven by Gil Andersen making it the fastest production car in America.[6] Also in 1927, Stutz won the AAA Championship winning every race and every Stutz vehicle entered finished. In 1929, three Stutzes, with bodies designed by Gordon Buehrig, built by Weymann's U.S. subsidiary, and powered by a 155 hp (116 kW; 157 PS), 322 cu in (5.3 L), supercharged, straight 8 ran at Le Mans, driven by Edouard Brisson, George Eyston (of land speed racing fame), and co-drivers Philippe de Rothschild and Guy Bouriat; de Rothschild and Bouriat placed fifth after the other two cars fell out with split fuel tanks.[4]

Stutz Motor acquired the manufacturing rights for the Pak-Age-Car, a light delivery vehicle that they had been distributing since 1927. A total of 15 new Stutz models were introduced at the 1932 New York Motor Show by Charles Schwab including the Pak-Age-Car. The delivery vehicle was put into production by Stutz's Package Car Division in March 1933 and the production of automobiles stopped.[8] When production ended in 1935 35,000 cars had been manufactured. Stutz Motor was charged by stock manipulation again in 1935, but without the excesses that occurred in 1920.

Stutz Motor filed for bankruptcy in April 1937, though its assets exceeded its liabilities. Creditors were unable to agree on a plan for revival and in April 1939, the bankruptcy court ordered its liquidation.[9]

Models

[edit]- 1911–1925 Bearcat

- 1926–1935 8-Cylinder

- Stutz Vertical Eight AA

- Stutz Vertical Eight BB

- Stutz Vertical Eight M

- Stutz Vertical Eight MA

- Stutz Vertical Eight MB

- Stutz Vertical Eight SV-16

- Stutz Vertical Eight DV-32

-

1929 Stutz Model M

-

1929 Stutz Model M LeBaron

-

1929 Stutz Roadster Supercharged

-

1930 Stutz SV16 Monte Carlo

-

1932 Stutz Convertible Coupe SV-16

-

1932 Stutz Vertical Eight SV-16 roadster body by Derham

-

1933 Stutz DV-32 Monte Carlo by Weymann

Stutz Motor Car Company Factory

[edit]Stutz Motor Car Company Factory | |

| Location | 1060 North Capitol Ave. and 217 West 10th St., Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′54″N 86°9′43″W / 39.78167°N 86.16194°W |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha) |

| Built | 1911, 1914 |

| Architect | Donald Graham (1911) Rubush & Hunter (1916-1920) |

| Architectural style | Daylight factory |

| NRHP reference No. | 100008060[10] |

| Added to NRHP | August 23, 2022 |

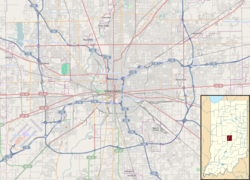

The Stutz Motor Car Company Factory, now known as the Stutz Factory, was the manufacturing facility and former headquarters of the Stutz Motor Company located at 1060 North Capitol Ave. and 217 West 10th St. in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana. The site consists of two building, the Stutz Factory and the Ideal Motor Car Company Building. The Stutz Factory (now known as Stutz I) occupies 5 acres (2.0 ha) of space, bounded by West 11th and 10th streets to the north and south and North Capitol and Senate avenues to the east and west. The Ideal Motor Car Company building (now known as Stutz II) is located directly to the south of the factory, with its boundaries as West 10th street to the north, North Senate Avenue to the west, and Roanoke Street to the east.

Both structures were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2022.[10]

Buildings

[edit]The original Ideal Motor Car Company building was constructed on the southwest corner of West 10th and North Roanoke streets in 1911. This portion of the building was added to in 1937, bringing the northwest portion of the building to three stories. A large-scale addition occurred 1941, which expanded the building's overall footprint to North Senate Avenue. The building was again expanded in 1946 and c. 1970. Other than the part of the building updated in 1937, the remaining structure is one story and constructed with concrete.[1]

The factory site is a set of seven interconnected buildings constructed between 1914 and c. 1967. Each building is constructed using concrete, and are connected by brick bridges across the upper three stories.[1] The first building of the factory (Building A) was constructed on the southeast corner of the city block, at the northwest corner of West 10th Street and North Capitol Avenues. The second building (Building B) was built in 1916 directly to the north of Building A. The third structure (Building F) was built in 1917, and added to in 1919, on the southwest corner of the city block. Buildings C and D were built to the north of Buildings B and F, and completed in 1920. Building E was also completed in 1920, and located directly to the north of Building C. Lastly, Building G was an addition to Building D that was completed around 1967. Buildings A, B, C, and E are connected using the brick bridges, while Buildings D, F, and G were connected by closing off unused alleys in the 1950s.[1]

The Stutz Factory is constructed in the Daylight Factory style. Daylight Factory is a type of reinforced concrete frame industrial building that utilized a patented modular structural system that allowed larger windows and increased lighting into the building.[1]

Adaptive reuse

[edit]After the Stutz company folded, Eli Lilly and Company moved into the space in 1940. Lilly used the factory to house its Creative Packaging division until 1982.[11][12]

After sitting vacant for more than a decade, Indianapolis-based real estate developer Turner Woodard purchased the Stutz Factory in 1993.[12] Woodard reimagined the space as an artist community, with an annual artist showcase that became a focal point of the Indianapolis arts community. The building also housed other small businesses.[12]

In 2021, Woodard sold the building to real estate investment firm SomeraRoad, who planned to redevelop the site into a work-play destination.[11] After a $100 million redevelopment, the new Stutz site reopened in May 2023 with restaurants, a coffee shop, a bakery, and a bar. The building is also the house of the annual "Butter" fine art fair put on by GANGGANG and a number of artist spaces.[13][14]

Revival as Stutz Motor Car of America

[edit] | |

| Industry |

|

|---|---|

| Founded | Indianapolis, Indiana, United States (1968) |

| Headquarters | , United States |

Area served | Worldwide |

| Services | Luxury vehicles |

In August 1968, New York banker James O'Donnell raised funds and incorporated Stutz Motor Car of America. A prototype of Virgil Exner's Stutz Blackhawk was produced by Ghia, and the car debuted in 1970. All these cars used General Motors running gear, featuring perimeter-type chassis frames, automatic transmission, power steering and power brakes with discs at the front. Features included electric windows, air conditioning, central locking, electric seats, and leather upholstery. The sedans typically included a console for beverages in the rear seat. Engines were V8s, originally 400 or 460 cubic inches (6.6 or 7.5 L), but by 1984 the Victoria, Blackhawk, and Bearcat came with a 160 hp (119 kW; 162 PS), 350.0-cubic-inch (5.7 L) engine while the Royale had a 424.8-cubic-inch (7.0 L) Oldsmobile engine rated at 180 hp (134 kW; 182 PS).

This incarnation of Stutz had some reasonable success selling newly designed Blackhawks, Bearcats, Royale Limousines, IV Portes, and Victorias. Elvis Presley bought the first Blackhawk in 1971, and later purchased three more. Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Evel Knievel, Barry White, and Sammy Davis Jr. all owned Stutz cars. The Stutz Blackhawk owned by Lucille Ball was for a time on display at the Imperial Palace Hotel and Casino Auto Collection in Las Vegas. The Stutz was marketed as the "World's Most Expensive Car" with a Royale limousine priced at $285,000 and a Blackhawk coupé over US$115,000 in 1984.[15] However, other producers sold secret cars for much more, and the much more expensive Ferrari F40 appeared just 2 years later.

Production was limited and an estimated 617 cars were built during the company's first 25 years of existence (1971–1995). Sales of Stutz began to wane in 1985, but continued until 1995. Warren Liu became its main shareholder and took over ownership of Stutz Motor Cars in 1982.

Stutz models II

[edit]

- Stutz Motor Car of America (Neoclassic automobiles)

- 1970–1987 Blackhawk (coupe)

- 1970–1979 - based on the Pontiac Grand Prix

- 1980–1987 - based on the Pontiac Bonneville

- 1979–1995 Bearcat (convertible)

- 1977 - a converted Blackhawk

- 1979 - based on the Pontiac Grand Prix

- 1980–1986 - based on the Pontiac Bonneville, Buick LeSabre, or Oldsmobile Delta 88 Royale

- 1987–1995 - based on the Pontiac Firebird or Chevrolet Camaro

- 1970–1987 Duplex/IV-Porte/Victoria (sedan)

- 197? Duplex

- 1977–1987 IV-Porte - based on the Pontiac Bonneville, Buick LeSabre, or Oldsmobile 88

- 1981– 1987 Victoria

- Diplomatica/Royale (limousine)

- Diplomatica - based on the Cadillac DeVille

- Royale - super-long limousine

- 1984– Defender/Gazelle/Bear - Chevrolet Suburban-based armored SUV

- Gazelle - military SUV with mounted machine gun

- Bear - four-door convertible

- 1970–1987 Blackhawk (coupe)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Indiana State Historic Architectural and Archaeological Research Database (SHAARD)" (Searchable database). Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved April 27, 2024. Note: This includes Amanda K. Loughlin (May 2022). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Stutz Motor Car Company Factory" (PDF). Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Listing Statements of the New York Stock Exchange, September 13, 1916.

- ^ Stutz Revived. TIME magazine, page 34, July 27, 1931.

- ^ a b Buehrig, Gordon M. & Jackson, William S. (1975). Rolling Sculpture: A Designer and his Work. Newfoundland, NJ: Haessner Publishing. ISBN 087799045X.[page needed]

- ^ Kettlewell, Mike (1974). "Le Mans". In Northey, Tom (ed.). World of Automobiles. Vol. 10. London: Orbis Publishing. p. 1176.

- ^ a b Wise, David Burgess (1974). "Stutz". In Northey, Tom (ed.). World of Automobiles. Vol. 19. London: Orbis Publishing. p. 2230.

- ^ Twite, Mike (1974). "Frank Lockhart". In Northey, Tom (ed.). World of Automobiles. Vol. 11. London: Orbis Publishing. p. 1210.

- ^ Sigur E. Whitaker. The Indianapolis Automobile Industry: A History, 1893–1939 Mcfarland, Jefferson NC, 2018 ISBN 9781476666914

- ^ Brooks, John (August 16, 1969). "A Corner in Stutz". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 8/22/2022 through 8/26/2022. National Park Service. August 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "Original Stutz Factory". The Stutz Club, Inc. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Allan, Marc D. (July 12, 2022). "Inside The Stutz Controversy". Indianapolis Monthly. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ Mullins, Marc (May 12, 2023). "Historic Stutz building will reopen after multi-million-dollar revamp". WRTV. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ Bongiovanni, Domenica (August 29, 2024). "Butter 2024: What to know about the art fair at the Stutz". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ Lösch, Annamaria, ed. (1984). World Cars 1984. Pelham, NY: Herald Books.[page needed]

External links

[edit] Media related to Stutz Motor Car Company at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stutz Motor Car Company at Wikimedia Commons- The Stutz Club Online

- Stutz in the Encyclopedia of Indianapolis

- Stutz vehicles

- Defunct motor vehicle manufacturers of the United States

- Luxury motor vehicle manufacturers

- Sports car manufacturers

- Motor vehicle manufacturers based in Indiana

- Manufacturing companies based in Indianapolis

- Defunct companies based in Indianapolis

- 1914 establishments in Indiana

- 1935 disestablishments in Indiana

- 1971 establishments in Indiana

- 1992 disestablishments in Indiana

- Vehicle manufacturing companies established in 1911

- Vehicle manufacturing companies disestablished in 1935

- Vehicle manufacturing companies established in 1971

- Vehicle manufacturing companies disestablished in 1992

- 1910s cars

- 1920s cars

- 1930s cars

- 1980s cars

- 1990s cars

- Brass Era vehicles

- Vintage vehicles

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Indiana

- Industrial buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Indiana

- Buildings and structures in Indianapolis

- National Register of Historic Places in Indianapolis

- Motor vehicle manufacturing plants on the National Register of Historic Places

- Transportation buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Indiana

- Transportation buildings and structures in Marion County, Indiana