Streptomyces griseus

| Streptomyces griseus | |

|---|---|

| |

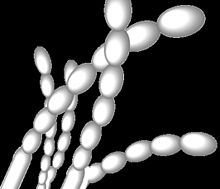

| Spore arrangement in Streptomyces griseus. Grey spores arranged in straight chains, as is typical of these strains.[1][2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Actinomycetota |

| Class: | Actinomycetia |

| Order: | Streptomycetales |

| Family: | Streptomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Streptomyces |

| Species: | S. griseus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Streptomyces griseus (Krainsky 1914)

Waksman and Henrici 1948 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Streptomyces griseus is a species of bacteria in the genus Streptomyces commonly found in soil. A few strains have been also reported from deep-sea sediments. It is a Gram-positive bacterium with high GC content. Along with most other streptomycetes, S. griseus strains are well known producers of antibiotics and other such commercially significant secondary metabolites. These strains are known to be producers of 32 different structural types of bioactive compounds. Streptomycin, the first antibiotic ever reported from a bacterium, comes from strains of S. griseus. Recently, the whole genome sequence of one of its strains had been completed.

The taxonomic history of S. griseus and its phylogenetically related strains has been turbulent. S. griseus was first described in 1914 by Krainsky, who called the species Actinomyces griseus.[3] The name was changed in 1948 by Waksman and Henrici to Streptomyces griseus. The interest in these strains stems from their ability to produce streptomycin, a compound which demonstrated significant bactericidal activity against organisms such as Yersinia pestis (the causative agent of plague) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (the causative agent of tuberculosis). Streptomycin was discovered in the laboratory of Selman Waksman, although his PhD student Albert Schatz probably did most of the work on these strains of bacteria and the antibiotic they produce.[4]

Taxonomy

[edit]Streptomyces is the largest genus of the Actinomycetota and is the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae.[5] These are Gram-positive bacteria with high GC content[5] and are characterised by a complex secondary metabolism.[6] They produce over two-thirds of the clinically useful antibiotics of natural origin.[7] Streptomycetes are found predominantly in soil and in decaying vegetation, and most produce spores. Streptomycetes are noted for their distinct "earthy" odor which results from production of a volatile metabolite, geosmin.[6]

Like other streptomycetes, S. griseus has a high GC content in its genome,[8] with an average of 72.2%.[9] The species was first classified within the genus Streptomyces by Waksman and Henrici in 1948.[10] The taxonomy of S. griseus and its evolutionarily related strains have been a considerable source of confusion for microbial systematists.[2] 16S rRNA gene sequence data have been used to recognise the related strains, and are called S. griseus 16S rRNA gene clade.[2] The strains of this clade have homogeneous phenotypic properties[11] but show substantial genotypic heterogenecity based on genomic data.[12] Several attempts are still made to solve this issue using techniques such as DNA:DNA homology[2] and multilocus sequence typing.[13][14] A whole genome sequence was carried out on the IFO 13350 strain of S. griseus.[9]

Physiology and morphology

[edit]S. griseus and its related strains have recently been shown to be alkaliphilic, i.e., they grow best at alkaline pH values. Although these organisms grow in a wide pH range (from 5 to 11), they show a growth optimum at pH 9.[10] They produce grey spore masses and grey-yellow reverse pigments when they grow as colonies.[2] The spores have smooth surfaces and are arranged as straight chains.[1]

Ecology

[edit]S. griseus strains have been isolated from various ecologies, including stell waste tips,[15] rhizosphere,[16] deep sea sediments[17] and coastal beach and dune sand systems.[10] Recent studies have indicated the strains of S. griseus might be undergoing ecology-specific evolution, giving rise to genetic variation with the specific ecology, termed ecovars.[13]

Antibiotic production

[edit]Interest in the genus Streptomyces for antibiotics came after the discovery of the antibiotic streptomycin in a S. griseus strain in 1943.[18] The discovery of streptomycin, an antituberculosis antibiotic, earned Selman Waksman the Nobel Prize in 1952.[19] The award was not without controversy, since it excluded the nomination of Albert Schatz, who is now recognized as one of the major co-inventors of streptomycin.[4][20][21] The strains of this species are now known to be rich sources of antibiotics and to produce 32 different structural types of commercially significant secondary metabolites.[22][23] Furthermore, the genomic studies have revealed a single strain of S. griseus IFO 13350 has the capacity to produce 34 different secondary metabolites.[24]

Etymology

[edit]By 1943, Albert Schatz, a PhD student working in Selman Waksman’s laboratory, had isolated streptomycin from Streptomyces griseus (from the Greek strepto- ("twisted") + mykēs ["fungus"] and the Latin griseus, “gray”).[25]

The official New Jersey state microbe

[edit]S. griseus was designated the official New Jersey state microbe in legislation submitted by Senator Sam Thompson (R-12) in May 2017 and Assemblywoman Annette Quijano (D-20) in June 2017.[26][27]

The organism was chosen because it is a New Jersey native that made unique contributions to healthcare and scientific research worldwide. A strain of S. griseus that produced the antibiotic streptomycin was discovered in New Jersey in “heavily manured field soil” from the New Jersey Agricultural Experimental Station by Albert Schatz in 1943.[28] Streptomycin is noteworthy because it is the first significant antibiotic discovered after penicillin, the first systemic antibiotic discovered in America, the first antibiotic active against tuberculosis, and the first-line treatment for plague. Moreover, New Jersey was the home of Selman Waksman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his systematic studies of antibiotic production by S. griseus and other soil microbes.[29]

The bill, S1729, was signed into law by NJ Governor Phil Murphy May 2019.

See also

[edit]- CRT (genetics), gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of carotenoids

References

[edit]- ^ a b Amano, S; S. Miyadoh; T. Shomura. "Streptomyces griseus M-1027". Digital Atlas of Actinomycetes. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ a b c d e Liu, Zhiheng; Shi, Yanlin; Zhang, Yamei; Zhou, Zhihong; Lu, Zhitang; Li, Wei; Huang, Ying; Rodríguez, Carlos; Goodfellow, Michael (2005). "Classification of Streptomyces griseus (Krainsky 1914) Waksman and Henrici 1948 and related species and the transfer of 'Microstreptospora cinerea' to the genus Streptomyces as Streptomyces yanii sp. nov". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 55 (4): 1605–10. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63654-0. PMID 16014489.

- ^ Krainsky, A (1914). "Die Aktinomyceten und ihren Bedeutung in der Natur". Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg Abt II (in German). 41: 649–688.

- ^ a b Wainwright, M. (1991). "Streptomycin: discovery and resultant controversy". Journal of the History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 13 (1): 97–124. PMID 1882032.

- ^ a b Kämpfer P (2006). "The Family Streptomycetaceae, Part I: Taxonomy". In Dworkin, M; et al. (eds.). The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria. Berlin: Springer. pp. 538–604. ISBN 0-387-25493-5.

- ^ a b Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-144329-1.[page needed]

- ^ Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA (2000). Practical Streptomyces Genetics (2nd ed.). Norwich, England: John Innes Foundation. ISBN 0-7084-0623-8.[page needed]

- ^ Paulsen, I.T. (1996). "Carbon metabolism and its regulation in Streptomyces and other high GC Gram-positive bacteria". Research in Microbiology. 147 (6–7): 535–41. doi:10.1016/0923-2508(96)84009-5. PMID 9084767.

- ^ a b "Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350 Genome". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ a b c Antony-Babu, Sanjay; Goodfellow, Michael (2008). "Biosystematics of alkaliphilic streptomycetes isolated from seven locations across a beach and dune sand system". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 94 (4): 581–91. doi:10.1007/s10482-008-9277-4. PMID 18777141.

- ^ Lanoot, Benjamin; Vancanneyt, Marc; Hoste, Bart; Vandemeulebroecke, Katrien; Cnockaert, Margo C.; Dawyndt, Peter; Liu, Zhiheng; Huang, Ying; Swings, Jean (2005). "Grouping of streptomycetes using 16S-ITS RFLP fingerprinting". Research in Microbiology. 156 (5–6): 755–62. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2005.01.017. PMID 15950131.

- ^ Lanoot, Benjamin; Vancanneyt, Marc; Dawyndt, Peter; Cnockaert, Margo; Zhang, Jianli; Huang, Ying; Liu, Zhiheng; Swings, Jean (2004). "BOX-PCR Fingerprinting as a Powerful Tool to Reveal Synonymous Names in the Genus Streptomyces. Emended Descriptions are Proposed for the Species Streptomyces cinereorectus, S. Fradiae, S. Tricolor, S. Colombiensis, S. Filamentosus, S. Vinaceus and S. Phaeopurpureus". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 27 (1): 84–92. Bibcode:2004SyApM..27...84L. doi:10.1078/0723-2020-00257. PMID 15053325.

- ^ a b Antony-Babu, Sanjay; Stach, James E. M.; Goodfellow, Michael (2008). "Genetic and phenotypic evidence for Streptomyces griseus ecovars isolated from a beach and dune sand system". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 94 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1007/s10482-008-9246-y. PMID 18491216.

- ^ Guo, Yinping; Zheng, Wen; Rong, Xiaoying; Huang, Ying (2008). "A multilocus phylogeny of the Streptomyces griseus 16S rRNA gene clade: Use of multilocus sequence analysis for streptomycete systematics". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 58 (1): 149–59. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.65224-0. PMID 18175701.

- ^ Graf, Ellen; Schneider, Kathrin; Nicholson, Graeme; Ströbele, Markus; Jones, Amanda L; Goodfellow, Michael; Beil, Winfried; s¨Ssmuth, Roderich D; Fiedler, Hans-Peter (2007). "Elloxazinones a and B, New Aminophenoxazinones from Streptomyces griseus Acta 2871†". The Journal of Antibiotics. 60 (4): 277–84. doi:10.1038/ja.2007.35. PMID 17456980.

- ^ Goodfellow, M; Williams, S T (1983). "Ecology of Actinomycetes". Annual Review of Microbiology. 37: 189–216. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001201. PMID 6357051.

- ^ Pathom-Aree, Wasu; Stach, James E. M.; Ward, Alan C.; Horikoshi, Koki; Bull, Alan T.; Goodfellow, Michael (2006). "Diversity of actinomycetes isolated from Challenger Deep sediment (10,898 m) from the Mariana Trench". Extremophiles. 10 (3): 181–9. doi:10.1007/s00792-005-0482-z. PMID 16538400.

- ^ Newman, David J.; Cragg, Gordon M.; Snader, Kenneth M. (2000). "The influence of natural products upon drug discovery (Antiquity to late 1999)". Natural Product Reports. 17 (3): 215–34. doi:10.1039/a902202c. PMID 10888010.

- ^ Wallgren, A. "Presentation Speech: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1952". Nobel Prize Foundation. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Wainwright, M. (1990). Miracle Cure: The Story of Penicillin and the Golden Age of Antibiotics. Blackwell. ISBN 9780631164920. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Pringle, Peter (2012). Experiment Eleven: Dark Secrets Behind the Discovery of a Wonder Drug. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-1620401989.

- ^ Strohl, William R (2004). "Antimicrobials". In Bull, Alan (ed.). Microbial diversity and bioprospecting. ASM publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 1-55581-267-8.

- ^ Zhang, Lixin (2005). "Integrated Approaches for Discovering Novel Drugs From Microbial Natural Products". In Zhang, Lixin (ed.). Natural products drug discovery and therapeutic medicine. Humana Press. pp. 33–55. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-976-9_2. ISBN 978-1-58829-383-1.

- ^ Ohnishi, Yasuo; Ishikawa, Jun; Hara, Hirofumi; Suzuki, Hirokazu; Ikenoya, Miwa; Ikeda, Haruo; Yamashita, Atsushi; Hattori, Masahira; Horinouchi, Sueharu (2008). "Genome Sequence of the Streptomycin-Producing Microorganism Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (11): 4050–60. doi:10.1128/JB.00204-08. PMC 2395044. PMID 18375553.

- ^ Henry, Ronnie (March 2019). "Etymologia: Streptomycin". Emerg Infect Dis. 25 (3): 450. doi:10.3201/eid2503.et2503. PMC 6390759. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

Citing public domain text from the CDC.

- ^ "New Jersey S3190 | 2016-2017 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ "New Jersey A4900 | 2016-2017 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ Schatz A, Bugie E, Waksman SE (1944). "Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 55: 66–69. doi:10.3181/00379727-55-14461.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1952". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-11-16.