Antiphospholipid syndrome

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hughes syndrome,[1] aCL syndrome, anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome, lupus anticoagulant syndrome[2] |

| |

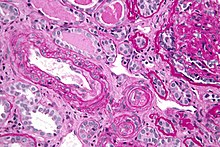

| Micrograph showing an advanced thrombotic microangiopathy, as may be seen in APLA syndrome. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain. | |

| Specialty | Immunology, hematology, rheumatology |

Antiphospholipid syndrome, or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS or APLS), is an autoimmune, hypercoagulable state caused by antiphospholipid antibodies. APS can lead to blood clots (thrombosis) in both arteries and veins, pregnancy-related complications, and other symptoms like low platelets, kidney disease, heart disease, and rash. Although the exact etiology of APS is still not clear, genetics is believed to play a key role in the development of the disease.[3]

Diagnosis is made based on symptoms and testing, but sometimes research criteria are used to aid in diagnosis. The research criteria for definite APS requires one clinical event (i.e. thrombosis or pregnancy complication) and two positive blood test results spaced at least three months apart that detect lupus anticoagulant, anti-apolipoprotein antibodies, and/or anti-cardiolipin antibodies.[4]

Antiphospholipid syndrome can be primary or secondary.

• Primary antiphospholipid syndrome occurs in the absence of any other related disease.

• Secondary antiphospholipid syndrome occurs with other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

In rare cases, APS leads to rapid organ failure due to generalised thrombosis; this is termed "catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome" (CAPS or Asherson syndrome) and is associated with a high risk of death.

Antiphospholipid syndrome often requires treatment with anticoagulant medication to reduce the risk of further episodes of thrombosis and improve the prognosis of pregnancy. The anticoagulant medication used for treatment may differ depending on the circumstance, such as pregnancy.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Antiphospholipid syndrome is known for causing arterial or venous blood clots, in any organ system, and pregnancy-related complications. While blood clots and pregnancy complications are the most common and diagnostic symptoms associated with APS, other organs and body parts may be affected like platelet levels, heart, kidneys, brain, and skin.[4][5] Also, people with APS may have symptoms associated with other autoimmune diseases like lupus erythematosus that are not caused by APS because APS can occur at the same time as other autoimmune diseases.

Blood clots

[edit]In APS patients, the most common venous event is deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities, and the most common arterial event is stroke.[6] People with a blot clot in their extremities may experience swelling, pain, or redness in the affected area.[7] People experiencing a stroke can experience a variety of symptoms depending on what blood vessel in the brain is affected. Symptoms include but are not limited to trouble speaking, loss of sensation, or weakness in one side of the face or body.[8] Blood clots can also occur in the lungs, which may cause trouble breathing or chest pain, and they can occur in the heart, which could lead to a heart attack.[5]

Blood clots in patients with APS are often considered unprovoked, which means they occur in the absence of conditions that typically cause blood clots (i.e. prolonged sedentary behavior, immoblization, infection, cancer). However, a person can develop a provoked blood clot while having APS due to APS causing an increased risk of blood clot development.[5] Exogenous estrogen therapies, such as estrogen-based contraceptives, significantly increase the risk of developing blood clots for patients with APS.[9]

Pregnancy-related complications

[edit]In pregnant people affected by APS, there is an increased risk of recurrent miscarriage, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia.[10][11] Recurrent miscarriages associated with APS typically occur prior to 10th week of gestation, but miscarriage associated with APS can also occur after the 10th week of gestation.[11] Certain causes must be excluded prior to attributing these complications to APS. Also, in pregnant individuals with lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome is responsible for most of the miscarriages in later trimesters.[12]

Other symptoms

[edit]Other common findings that suggest APS are low platelet count, heart valve disease, high blood pressure in the lungs, kidney disease, and a rash called livedo reticularis.[5] There are also associations between antiphospholipid antibodies and different neurologic manifestations[13] including headache,[14] migraine,[15] epilepsy,[16] and dementia[17] although more research is needed to prove that these symptoms are indicative of APS. Cancer is also observed to occur at the same time in some patients with APS.[18]

Mechanisms

[edit]Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disease, in which "antiphospholipid antibodies" react against proteins that bind to anionic phospholipids on plasma membranes. Anticardiolipin antibodies, β2glycoprotein 1, and lupus anticoagulant are antiphospholipid antibodies that are thought to clinically cause disease. These antibodies lead to blood clots and vascular disease in the presence (secondary APS) or absence (primary APS) of other diseases.[19] While the exact functions of the antibodies are not known, the activation of the coagulation system is evident.

Anti-ApoH and a subset of anti-cardiolipin antibodies bind to ApoH. ApoH inhibits protein C, a glycoprotein with important regulatory function of coagulation (inactivates Factor Va and Factor VIIIa). Lupus anticoagulant antibodies bind to prothrombin, thus increasing its cleavage to thrombin, its active form.[citation needed]

Other antibodies associated with APS include antibodies against protein S and annexin A5. Protein S is a co-factor of protein C, which is one of the body's own anti-clotting factors. Annexin A5 forms a shield around negatively charged phospholipid molecules, which reduces the membrane's ability to participate in clotting. Thus, antibodies against protein S and anti-annexin A5 decrease protein C efficiency and increase phospholipid-dependent coagulation steps respectively, which leads to increased clotting potential.[20][21]

The lupus anticoagulant antibodies are those that show the closest association with thrombosis; those that target β2glycoprotein 1 have a greater association with thrombosis than those that target prothrombin. Anticardiolipin antibodies are associated with thrombosis at moderate to high titres (over 40 GPLU or MPLU). Patients with both lupus anticoagulant antibodies and moderate or high titre anticardiolipin antibodies show a greater risk of thrombosis than with one alone.[citation needed]

The increased risks of recurrent miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth by antiphospholipid antibodies, as supported by in vitro studies, include decreased trophoblast viability, syncytialization and invasion, deranged production of hormones and signalling molecules by trophoblasts, as well as activation of coagulation and complement pathways.[10]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome is often made through the combination of symptoms and testing. Repeat antibody testing 12 weeks after discovering the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) is needed to establish a diagnosis because false positives can occur.[4][22][23]

While APS was previously categorized into primary and secondary APS based on the absence or presence of concurrent autoimmune disease respectively, the 16th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force categorizes APS into 6 categories:[5]

- no symptoms in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies

- pregnancy related

- blood clot (venous or arterial) related

- microvascular (small blood vessel)

- catastrophic

- non-blood clot (i.e. kidney, low platelets, heart valve disease) related

In their report, they acknowledge that some individuals may qualify for more than one category based on symptoms.[5]

Research criteria

[edit]Because there are no agreed upon diagnostic criteria for APS, research classification criteria are sometimes used to aid in diagnosis.[5] The Sapporo APS classification criteria (1998, published in 1999)[24] were replaced by the Sydney criteria in 2006.[11] The Sydney criteria requires one clinical (thrombosis or pregnancy related) manifestation and persistent presence of one or more APS antibody.[11] In the 2023 American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism joint criteria they added heart related symptoms and low platelet levels as clinical criteria and changed some thresholds and specifics for antibody testing.[4] However, all previously proposed research criteria are meant to create a standardized group of individuals with APS in order to increase accuracy in statistical analysis, so the criteria are not be representative of all individuals with APS.[4][5] Thus, people who do not meet all of the criteria could still have APS.

In terms of catastropic APS, the International Consensus Statement is commonly used for diagnosis. Based on this statement, Definite CAPS diagnosis requires:[25]

- Blood clot in three or more organs or tissues and

- Development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than a week and

- Evidence of small vessel blood clot in at least one organ or tissue and

- Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL.

Lab testing

[edit]Antiphospholipid antibody tests are either liquid-phase coagulation assays to detect lupus anticoagulant or solid phase ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) to detect anti-cardiolipin antibodies and β2 glycoprotein 1.[23] The use of testing for antibodies specific for individual targets of aPL such as phosphatidylserine is currently under debate.[citation needed]

Lupus anticoagulant

[edit]This is tested for by using two coagulation tests that are phospholipid-sensitive, due to the heterogeneous nature of the lupus anticoagulant antibodies. A patient with lupus anticoagulant antibodies on initial screening will typically have been found to have a prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) that does not correct in an 80:20 mixture with normal human plasma (50:50 mixes with normal plasma are insensitive to all but the highest antibody levels). The PTT (plus 80:20 mix), dilute Russell's viper venom time, silica clotting time and prothrombin time (using a lupus-sensitive thromboplastin) are the principal tests used for the detection of lupus anticoagulant. The Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis no longer recommends the kaolin clotting time, dilute thromboplastin time, and Taipan/Ecarin snake venom based assays due to implementation issues from a variety of factors.[22]

Distinguishing a lupus anticoagulant antibody from a specific coagulation factor inhibitor (e.g.: factor VIII) is normally achieved by differentiating the effects of a lupus anticoagulant on factor assays from the effects of a specific coagulation factor antibody. The lupus anticoagulant will inhibit all the contact activation pathway factors (factor VIII, factor IX, factor XI and factor XII). Lupus anticoagulant will also rarely cause a factor assay to give a result lower than 35 iu/dl (35%) whereas a specific factor antibody will rarely give a result higher than 10 iu/dl (10%). Monitoring IV anticoagulant therapy by the PTT ratio is compromised due to the effects of the lupus anticoagulant and in these situations is generally best performed using a chromogenic assay based on the inhibition of factor Xa by antithrombin in the presence of heparin.[citation needed]

Anticardiolipin and β2glycoprotein 1 antibodies

[edit]Anti-cardiolipin antibodies can be detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) immunological test, which screens for the presence of β2glycoprotein 1 dependent anticardiolipin antibodies. A low platelet count and positivity for antibodies against phosphatidylserine may also be observed in a positive diagnosis.[citation needed]

False results

[edit]The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies may not indicate APS, which is why considering the symptoms present and retesting antibody levels is essential. People may be transiently positive, incorrectly positive, or incorrectly negative if they are tested when the following is occurring:[22]

- infection

- pregnancy

- blood clot

- states in which acute-phase proteins, bilirubin, or fats are elevated

- anticoagulation (i.e. warfarin, heparin)

It is recommended to generally re-test people 12 weeks after the first positive test to confirm that it was correct, except for those who test positive during pregnancy.[22] For that group, it is recommend to wait 3 months to re-test if possible. Re-testing is more nuanced if the person is taking an anticoagulant, which may require not taking the medication for a certain period of time or specifically timing the test.[22]

Also, patients who have certain antiphospholipid antibodies may have false positive VDRL test, which aims to detect a syphilis infection. This occurs because the aPL bind to the lipids in the test and make it come out positive. A more specific test for syphilis, FTA-Abs, will not have a false-positive result in the presence of aPL.[citation needed]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]For people with blood clot related APS, other conditions that can cause blood clots should be considered including but not limited to acquired blood clots, genetic thrombophilia, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Genetic thrombophilia can coexist in some patients with APS.[citation needed] For people with pregnancy related APS, other causes of recurrent miscarriage should be considered before the diagnosis of APS, such as genetic, structural, or immune abnormalities.

Treatment

[edit]Treatment depends on a person's APS symptoms.[26] Typically a medication that decreases the body's ability to form blood clots is given to prevent future clots. Low dose aspirin can be given to people who have APS antibodies but no symptoms, high risk individuals with lupus erythematosus and APS antibodies but no symptoms of APS, and non-pregnant people who had APS during pregnancy.[26][27] For those people with APS who have had a blood clot (venous or arterial), anticoagulants such as warfarin are used to prevent future clots.[26][27] If warfarin is used, the INR is kept between 2.0 and 3.0.[27] Direct-acting oral anticoagulants may be used as an alternative to warfarin, but not in people with APS who had a previous arterial blood clot[28][29] or are "triple positive" with all types of antiphospholipid antibody (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibody).[26][27][30][31] In people with arterial blood clot related APS, using direct-acting oral anticoagulants has shown to increase the risk of future arterial blood clots and should not be used.[28][29]

In pregnant women with only pregnancy related APS or only past blood clot related APS, low molecular weight heparin and low-dose aspirin are used instead of warfarin because of warfarin's ability to cause birth defects.[26][27] Heparin and aspirin together appears to make miscarriage less likely in pregnant women with APS.[27] Women with recurrent miscarriages are often advised to take aspirin and to start low molecular weight heparin treatment after missing a menstrual cycle.[citation needed] In refractory cases plasmapheresis may be used.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]Factors that increase likelihood of developing APS related future blood clots and pregnancy complications include:

- presence of all three antibodies (β2 glycoprotein 1, lupus anticoagulant, and anticardiolipin)[5]

- moderate to high levels of an APS antibody[5]

- presence of IgG APS antibodies[5]

Also, a history of previous blood clots in someone with APS increases the risk for certain pregnancy complications, such as death of the child, smaller sized baby, and blood clots during and after pregnancy.[32] Outside of people with APS having an increased risk of blood clots and pregnancy complications, people with APS generally have increased risk of atherosclerotic disease.[6][33]

Other risk stratification criteria for predicting blood clots and pregnancy complications have been proposed, such as the aPL Score and the Global APS score, but further data is needed to validate these tools.[5]

Epidemiology

[edit]Factors associated with developing antiphospholipid syndrome include:

- Genetic Markers: HLA-DR4, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DRw53[34]

- Race: Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans[citation needed]

- Sex: female [35]

- Age: 30-40s [35]

History

[edit]Antiphospholipid syndrome was described in full in the 1980s, by E. Nigel Harris and Aziz Gharavi. They published the first papers in 1983.[36][37] The syndrome was referred to as "Hughes syndrome" among colleagues after the rheumatologist Graham R.V. Hughes (St. Thomas' Hospital, London, UK), who brought together the team.[citation needed]

Research

[edit]According to a 2006 Sydney consensus statement,[11] it is advisable to classify APS into one of the following categories for research purposes:

- I: more than one laboratory criterion present in any combination;

- IIa: lupus anticoagulant present alone

- IIb: anti-cardiolipin IgG and/or IgM present alone in medium or high titers

- IIc: anti-β2 glycoprotein I IgG and/or IgM present alone in a titer greater than 99th percentile

References

[edit]- ^ Hughes G, Khamashta MA (2013-07-01). Hughes Syndrome: Highways and Byways. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781447151616. Archived from the original on 2017-03-31.

- ^ "Antiphospholipid syndrome". Autoimmune Registry Inc. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Islam, Md Asiful (2018). "Genetic risk factors in thrombotic primary antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review with bioinformatic analyses". Autoimmunity Reviews. 17 (3): 226–243. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.014. PMID 29355608 – via Science Direct.

- ^ a b c d e Barbhaiya M, Zuily S, Naden R, Hendry A, Manneville F, Amigo MC, et al. (October 2023). "The 2023 ACR/EULAR Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 75 (10): 1687–1702. doi:10.1002/art.42624. hdl:2027.42/178218. PMID 37635643. S2CID 263166505.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sciascia S, Radin M, Cecchi I, Levy RA, Erkan D (July 2021). "16th International congress on antiphospholipid antibodies task force report on clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome". Lupus. 30 (8): 1314–1326. doi:10.1177/09612033211020361. PMID 34039107. S2CID 235215484.

- ^ a b Cheng C, Cheng GY, Denas G, Pengo V (July 2021). "Arterial thrombosis in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS): Clinical approach and treatment. A systematic review". Blood Reviews. 48: 100788. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2020.100788. PMID 33341301. S2CID 229343584.

- ^ Kruger PC, Eikelboom JW, Douketis JD, Hankey GJ (June 2019). "Deep vein thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management". The Medical Journal of Australia. 210 (11): 516–524. doi:10.5694/mja2.50201. PMID 31155730. S2CID 173995098.

- ^ Ali M, van Os HJ, van der Weerd N, Schoones JW, Heymans MW, Kruyt ND, et al. (February 2022). "Sex Differences in Presentation of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Stroke. 53 (2): 345–354. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.034040. PMC 8785516. PMID 34903037.

- ^ Sammaritano, Lisa R. (2021-04-30). "Which Hormones and Contraception for Women with APS? Exogenous Hormone Use in Women with APS". Current Rheumatology Reports. 23 (6): 44. doi:10.1007/s11926-021-01006-w. ISSN 1534-6307.

- ^ a b Tong M, Viall CA, Chamley LW (2014). "Antiphospholipid antibodies and the placenta: a systematic review of their in vitro effects and modulation by treatment". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (1): 97–118. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu049. PMID 25228006.

- ^ a b c d e Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, et al. (February 2006). "International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 4 (2): 295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. hdl:11379/21509. PMID 16420554. S2CID 9752817.

- ^ "Lupus and Pregnancy". Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Kamal MA, Wong KK, Sasongko TH, Gan SH (2016). "'Non-Criteria' Neurologic Manifestations of Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Hidden Kingdom to be Discovered". CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 15 (10): 1253–1265. doi:10.2174/1871527315666160920122750. PMID 27658514.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Gan SH, Cavestro C, Wong KK (March 2018). "Coexistence of antiphospholipid antibodies and cephalalgia". Cephalalgia. 38 (3): 568–580. doi:10.1177/0333102417694881. PMID 28952322. S2CID 3954437.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Wong KK (May 2017). "Comorbid association of antiphospholipid antibodies and migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 16 (5): 512–522. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.03.005. PMID 28279839.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Cavestro C, Calcii C, Sasongko TH, Levy RA, Gan SH (August 2018). "Antiphospholipid antibodies in epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 17 (8): 755–767. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.025. PMID 29885542. S2CID 47014367.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Kamal MA, Gan SH, Sasongko TH, Wong KK (2017). "Presence of Anticardiolipin Antibodies in Patients with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 9: 250. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00250. PMC 5539075. PMID 28824414. S2CID 8364684.

- ^ Islam MA (August 2020). "Antiphospholipid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome in cancer: Uninvited guests in troubled times". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 64: 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.07.019. PMID 31351197. S2CID 198952872.

- ^ Islam MA, Alam F, Sasongko TH, Gan SH (2016). "Antiphospholipid Antibody-Mediated Thrombotic Mechanisms in Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Towards Pathophysiology-Based Treatment". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 22 (28): 4451–4469. doi:10.2174/1381612822666160527160029. PMID 27229722.

- ^ Triplett DA (November 2002). "Antiphospholipid antibodies". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 126 (11): 1424–1429. doi:10.5858/2002-126-1424-AA. PMID 12421152.

- ^ Rand JH (August 1998). "Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: new insights on thrombogenic mechanisms". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 316 (2): 142–151. doi:10.1097/00000441-199808000-00009. PMID 9704667.

- ^ a b c d e Devreese KM, de Groot PG, de Laat B, Erkan D, Favaloro EJ, Mackie I, et al. (November 2020). "Guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection and interpretation". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 18 (11): 2828–2839. doi:10.1111/jth.15047. PMID 33462974. S2CID 225955504.

- ^ a b Devreese KM, Ortel TL, Pengo V, de Laat B (April 2018). "Laboratory criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome: communication from the SSC of the ISTH". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 16 (4): 809–813. doi:10.1111/jth.13976. PMID 29532986. S2CID 3855310.

- ^ Wilson, W. A.; Gharavi, A. E.; Koike, T.; Lockshin, M. D.; Branch, D. W.; Piette, J. C.; Brey, R.; Derksen, R.; Harris, E. N.; Hughes, G. R.; Triplett, D. A.; Khamashta, M. A. (July 1999). "International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 42 (7): 1309–1311. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1309::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-F. ISSN 0004-3591. PMID 10403256.

- ^ Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, Erkan D, Boffa MC, Piette JC, et al. (July 2003). "Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines". Lupus. 12 (7): 530–534. doi:10.1191/0961203303lu394oa. PMID 12892393. S2CID 29222615.

- ^ a b c d e Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, Amoura Z, Cervera R, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. (October 2019). "EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults" (PDF). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 78 (10): 1296–1304. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213. PMC 11034817. PMID 31092409. S2CID 155101935.

- ^ a b c d e f Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, Tincani A, Ward MM (2019). "Management of thrombotic and obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults". RMD Open. 5 (1): e000924. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000924. PMC 6525610. PMID 31168416.

- ^ a b Khairani CD, Bejjani A, Piazza G, Jimenez D, Monreal M, Chatterjee S, et al. (January 2023). "Direct Oral Anticoagulants vs Vitamin K Antagonists in Patients With Antiphospholipid Syndromes: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 81 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.10.008. PMC 9812926. PMID 36328154.

- ^ a b Dufrost V, Wahl D, Zuily S (January 2021). "Direct oral anticoagulants in antiphospholipid syndrome: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials" (PDF). Autoimmunity Reviews. 20 (1): 102711. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102711. PMID 33197580. S2CID 226989043.

- ^ "Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing". www.nice.org.uk. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ Wu X, Cao S, Yu B, He T (October 2022). "Comparing the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus Vitamin K antagonists in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis. 33 (7): 389–401. doi:10.1097/mbc.0000000000001153. PMC 9594143. PMID 35867933.

- ^ Walter IJ, Klein Haneveld MJ, Lely AT, Bloemenkamp KW, Limper M, Kooiman J (October 2021). "Pregnancy outcome predictors in antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Autoimmunity Reviews. 20 (10): 102901. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102901. PMID 34280554.

- ^ Karakasis P, Lefkou E, Pamporis K, Nevras V, Bougioukas KI, Haidich AB, Fragakis N (June 2023). "Risk of Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients with Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Subjects With Antiphospholipid Antibody Positivity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Current Problems in Cardiology. 48 (6): 101672. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.101672. PMID 36841314. S2CID 257197368.

- ^ Iuliano A, Galeazzi M, Sebastiani GD (September 2019). "Antiphospholipid syndrome's genetic and epigenetic aspects". Autoimmunity Reviews. 18 (9): 102352. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102352. PMID 31323355. S2CID 198132495.

- ^ a b "Antiphospholipid Syndrome". American College of Rheumatology. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ Ruiz-Irastorza G, Crowther M, Branch W, Khamashta MA (October 2010). "Antiphospholipid syndrome". Lancet. 376 (9751): 1498–1509. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60709-X. hdl:2318/1609788. PMID 20822807. S2CID 25554663.

- ^ Hughes GR (October 1983). "Thrombosis, abortion, cerebral disease, and the lupus anticoagulant". British Medical Journal. 287 (6399): 1088–1089. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6399.1088. PMC 1549319. PMID 6414579.

Further reading

[edit]- Holden T (2003). Positive Options for Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS): Self-Help and Treatment. Hunter House (CA). ISBN 978-0-89793-409-1.

- Thackray K (2003). Sticky Blood Explained. Braiswick. ISBN 978-1-898030-77-5. A personal account of dealing with the condition.

- Hughes GR (2009). Understanding Hughes Syndrome: Case Studies for Patients. Springer. ISBN 978-1-84800-375-0. 50 case studies to help you work out whether you have it.