Sternocleidomastoid muscle

| Sternocleidomastoid | |

|---|---|

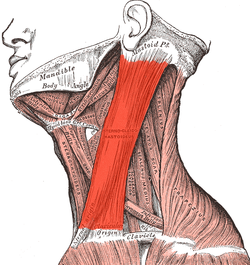

Neck muscles, with the sternocleidomastoid in bright red | |

The sternocleidomastoid (right muscle shown) can be clearly observed when rotating the head. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | (/ˌstɜːrnoʊˌklaɪdəˈmæsˌtɔɪd, -nə-, -doʊ-/[1][2]) |

| Origin | Manubrium and medial portion of the clavicle |

| Insertion | Mastoid process of the temporal bone, superior nuchal line |

| Artery | Occipital artery and the superior thyroid artery |

| Nerve | Motor: spinal accessory nerve sensory: cervical plexus Proprioceptive: ventral rami of C2-3 |

| Actions | Unilaterally: contralateral cervical rotation, ipsilateral cervical flexion Bilaterally: cervical flexion, elevation of sternum and assists in forced inhalation. |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus sternocleidomastoideus |

| TA98 | A04.2.01.008 |

| TA2 | 2156 |

| FMA | 13407 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is one of the largest and most superficial cervical muscles. The primary actions of the muscle are rotation of the head to the opposite side and flexion of the neck.[3] The sternocleidomastoid is innervated by the accessory nerve.[3]

Etymology and location

[edit]It is given the name sternocleidomastoid because it originates at the manubrium of the sternum (sterno-) and the clavicle (cleido-) and has an insertion at the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull.[4]

Structure

[edit]The sternocleidomastoid muscle originates from two locations: the manubrium of the sternum and the clavicle.[4] It travels obliquely across the side of the neck and inserts at the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull by a thin aponeurosis.[4][5] The sternocleidomastoid is thick and narrow at its center, and broader and thinner at either end.

The sternal head is a round fasciculus, tendinous in front, fleshy behind, arising from the upper part of the front of the manubrium sterni. It travels superiorly, laterally, and posteriorly.

The clavicular head is composed of fleshy and aponeurotic fibers, arises from the upper, frontal surface of the medial third of the clavicle; it is directed almost vertically upward.

The two heads are separated from one another at their origins by a triangular interval (lesser supraclavicular fossa) but gradually blend, below the middle of the neck, into a thick, rounded muscle which is inserted, by a strong tendon, into the lateral surface of the mastoid process, from its apex to its superior border, and by a thin aponeurosis into the lateral half of the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone.

Nerve supply

[edit]The sternocleidomastoid is innervated by accessory nerve of the same side.[6][7] It supplies only motor fibres. The cervical plexus supplies sensation, including proprioception, from the ventral primary rami of C2 and C3.[6]

Variation

[edit]The clavicular origin of the sternocleidomastoid varies greatly: in some cases the clavicular head may be as narrow as the sternal; in others it may be as much as 7.5 millimetres (0.30 in) in breadth.

When the clavicular origin is broad, it is occasionally subdivided into several slips, separated by narrow intervals. More rarely, the adjoining margins of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius are in contact. This would leave no posterior triangle.

The supraclavicularis muscle arises from the manubrium behind the sternocleidomastoid and passes behind the sternocleidomastoid to the upper surface of the clavicle.

Function

[edit]The function of this muscle is to rotate the head to the opposite side or obliquely rotate the head.[4] It also flexes the neck.[4] When both sides of the muscle act together, it flexes the neck and extends the head. When one side acts alone, it causes the head to rotate to the opposite side and flexes laterally to the same side (ipsilaterally).

It also acts as an accessory muscle of respiration, along with the scalene muscles of the neck.

Contraction

[edit]The signaling process to contract or relax the sternocleidomastoid begins in Cranial Nerve XI, the accessory nerve. The accessory nerve nucleus is in the anterior horn of the spinal cord around C1-C3, where lower motor neuron fibers mark its origin. The fibers from the accessory nerve nucleus travel upward to enter the cranium via the foramen magnum. The internal carotid artery to reach both the sternocleidomastoid muscles and the trapezius. After a signal reaches the accessory nerve nucleus in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, the signal is conveyed to motor endplates on the muscle fibers located at the clavicle. Acetylcholine (ACH) is released from vesicles and is sent over the synaptic cleft to receptors on the postsynaptic bulb. The ACH causes the resting potential to increase above -55mV, thus initiating an action potential which travels along the muscle fiber. Along the muscle fibers are t-tubule openings which facilitate the spread of the action potential into the muscle fibers. The t-tubule meets with the sarcoplasmic reticulum at locations throughout the muscle fiber, at these locations the sarcoplasmic reticulum releases calcium ions that results in the movement of troponin and tropomyosin on thin filaments. The movement of troponin and tropomyosin is key in facilitating the myosin head to move along the thin filament, resulting in a contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[8]

Anatomical landmark

[edit]

The sternocleidomastoid is within the investing fascia of the neck, along with the trapezius muscle, with which it shares its nerve supply (the accessory nerve). It is thick and thus serves as a primary landmark of the neck, as it divides the neck into anterior and posterior cervical triangles (in front and behind the muscle, respectively) which helps define the location of structures, such as the lymph nodes for the head and neck.[9]

Many important structures relate to the sternocleidomastoid, including the common carotid artery, accessory nerve, and brachial plexus.

Clinical significance

[edit]Examination of the sternocleidomastoid muscle forms part of the examination of the cranial nerves. It can be felt on each side of the neck when a person moves their head to the opposite side.[9]

The triangle formed by the clavicle and the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is used as a landmark in identifying the correct location for central venous catheterization.[10]

Contraction of the muscle gives rise to a condition called torticollis or wry neck, and this can have a number of causes. Torticollis gives the appearance of a tilted head on the side involved. Treatment involves physiotherapy exercises to stretch the involved muscle and strengthen the muscle on the opposite side of the neck. Congenital torticollis can have an unknown cause or result from birth trauma that gives rise to a mass or tumor that can be palpated within the muscle.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 390 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 390 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "Sternocleidomastoid". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ^ "Sternocleidomastoid". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ a b Kohan, Emil J.; Wirth, Garrett A. (2014). "Anatomy of the neck". Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 41 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2013.09.016. ISSN 1558-0504. PMID 24295343.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson, June K; Anderson, E Ratcliffe (2005-01-01), Robinson, June K; Sengelmann, Roberta D; Hanke, C William; Siegel, Daniel Mark (eds.), "1. Skin Structure and Surgical Anatomy", Surgery of the Skin, Edinburgh: Mosby, pp. 3–23, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-02752-6.50006-7, ISBN 978-0-323-02752-6, retrieved 2020-11-06

- ^ Gray, John C.; Grimsby, Ola (2012-01-01), Donatelli, Robert A. (ed.), "5. Interrelationship of the Spine, Rib Cage, and Shoulder", Physical Therapy of the Shoulder (5th ed.), Saint Louis: Churchill Livingstone, pp. 87–130, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4377-0740-3.00005-2, ISBN 978-1-4377-0740-3, retrieved 2020-11-20

- ^ a b Taira, Takaomi (2015-01-01), Tubbs, R. Shane; Rizk, Elias; Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Loukas, Marios (eds.), "28. Peripheral Nerve Surgical Procedures for Cervical Dystonia", Nerves and Nerve Injuries, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 413–430, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802653-3.00077-4, ISBN 978-0-12-802653-3, retrieved 2020-11-06

- ^ Salyer, Steven W. (2007-01-01), Salyer, Steven W. (ed.), "9. Neurological Emergencies", Essential Emergency Medicine, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 418–496, doi:10.1016/b978-141602971-7.10009-1, ISBN 978-1-4160-2971-7, retrieved 2020-11-06

- ^ Walker HK (1990). "64 Cranial Nerve XI: The Spinal Accessory Nerve". In Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (eds.). Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 0-409-90077-X. PMID 21250228. NBK387.

- ^ a b Fehrenbach, Margaret J.; Herring, Susan W. (2012). Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck. Elsevier. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4377-2419-6.

- ^ Denys, B. G.; Uretsky, B. F. (December 1991). "Anatomical variations of internal jugular vein location: impact on central venous access". Critical Care Medicine. 19 (12): 1516–1519. doi:10.1097/00003246-199112000-00013. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 1959371.