Charles Hazelius Sternberg

Charles Hazelius Sternberg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 15, 1850 |

| Died | July 20, 1943 (aged 93) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Paleontological collecting and studies |

| Children | George, Charles, and Levi |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

Charles Hazelius Sternberg (June 15, 1850 – July 20, 1943) was an American fossil collector and paleontologist. He was active in both fields from 1876 to 1928, and collected fossils for Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel C. Marsh, and for the British Museum, the San Diego Natural History Museum and other museums.

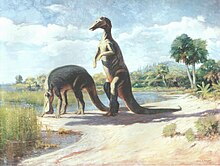

The Sternberg family is legendary in the history of paleontology. Charles Hazelius was the patriarch, and his three sons, George F. Sternberg, Charles Mortram Sternberg and Levi Sternberg were also professional fossil collectors. In 1908, the Sternbergs found a remarkable duckbill dinosaur mummy in the Lance Formation of eastern Wyoming, the first such fossil found. After spirited bidding, the fossil was sold to the American Museum of Natural History.[2]

Biography

[edit]Charles Hazelius Sternberg was born near Cooperstown, New York to Reverend Levi Sternberg and Margaret Levering Miller.[3] At the age of 17, Sternberg moved to Ellsworth County, Kansas where his older brother, Dr. George M. Sternberg, worked as a military surgeon at Fort Harker and owned a ranch. Once there, Sternberg became interested in collecting fossil leaves from the Dakota Sandstone Formation.[4] From 1875 to 1876, Sternberg studied at Kansas State University under noted paleontologist Benjamin Franklin Mudge, though Sternberg never earned a degree.[5]

In 1876, Edward Drinker Cope funded Sternberg's first formal expedition to Park, Kansas, and Sternberg continued to work with Cope for several field seasons in the years that followed.[4][5][1]: 32 Sternberg later collected fossils for Cope's rival in the Bone Wars, Othniel C. Marsh, working alongside John Bell Hatcher in Long Island, Kansas.[1]: 31–32 Sternberg also collected for various museums and institutions, and his work took him all over North America, including locations in California, Montana, Texas, and Canada.[5]

Sternberg moved to San Diego, California in 1921 and held the honorary title of Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the San Diego Natural History Museum.[4] He continued to lead fossil-hunting expeditions throughout North America and sold his specimens to museums and universities world-wide.[6] Sternberg's final expedition was to the Baja Peninsula in 1928.[4]

After his wife's death in 1938, Sternberg moved in with his son Levi Sternberg in Toronto, Canada, where he lived until his death aged 93.[4] Sternberg wrote two books about his paleontological adventures: "The Life of a Fossil Hunter" (1909)[7] and "Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada: A Sequel to The Life of a Fossil Hunter" (1917).[8]

Personal life

[edit]Sternberg married Anna Musgrave Reynolds on July 7, 1880. One son died in toddlerhood, and their only daughter died at age 20 in 1911.[3] Three sons survived into adulthood, George F. Sternberg (1883–1969), Charles Mortram Sternberg (1885–1981), and Levi Sternberg (1894–1976), who also had careers in vertebrate paleontology. They became famous for their collecting abilities and many discoveries, including the "Trachodon mummy", an exquisitely preserved specimen of Edmontosaurus annectens (see hadrosaurid). Son George was also a noted fossil hunter famous for finding a "fish within a fish" — a 13-foot (4.0 m) Xiphactinus which had inside it a nicely preserved, 6-foot (1.8 m) Gillicus arcuatus.

Charles Sternberg was a deeply religious man. He wrote devotional poetry and published a collection of poems called A Story of the Past: Or, the Romance of Science (1911). [9][10] In his old age, he would visit the American Museum of Natural History to view his finds, and one visit to the "Trachodon mummy" inspired the following quote:

My own body will crumble in dust, my soul return to the God who gave it, but the works of His hands, those animals of other days, will give joy and pleasure to generations yet unborn.

— Charles H. Sternberg[11]

Sternberg Museum

[edit]Fossils collected by Charles Sternberg, including dinosaurs from the western United States and Canada, are in museums around the world. Many of the fossils discovered by Charles Sternberg's son, George F. Sternberg, are on display in the Sternberg Museum of Natural History in Hays, Kansas.

In popular culture

[edit]- In Robert J. Sawyer's novel End of an Era (1994), the Canadian protagonists' time machine is named His Majesty's Canadian Timeship Charles Hazelius Sternberg, because of the two scientists journeying back to the Cretaceous era, one is a paleontologist. The narrator comments that "our timeship is almost universally known as the Sternberger, because to most people it looks like a fat hamburger."[12]

- Tim Bowling's novel The Bone Sharps (2007) centres about the fossil-hunting work of Charles Sternberg in Kansas, in 1876 and 1916. Secondary characters are Sternberg's young assistant, Scott, who served in the trenches of World War I; another bone hunter, Scott's fiancée (1916) and possibly widow (1975), Lily; and Charles Sternberg's deceased daughter, Maud; as well as Edward Drinker Cope and Cope's wife Annie.[13]

- In Dragon Teeth (published posthumously in 2017), Michael Crichton's novel about the Bone Wars, Cope is a protagonist and Sternberg a supporting character.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Dingus, Lowell (2018). King of the Dinosaur Hunters : the life of John Bell Hatcher and the discoveries that shaped paleontology. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781681778655.

- ^ Donald Prothero, The Story of the Dinosaurs in 25 Discoveries. 2019, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231186025

- ^ a b Everhart, Mike (October 13, 2004). "Charles H. Sternberg: Fossil Hunter". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ward, Penny. "Sternberg, Charles Hazelius (1850-1943)". San Diego Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c Aber, James. "Charles Hazelius Sternberg and sons, George F. Charles M. and Levi". History of Geology. Emporia State University. Archived from the original on February 11, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Sternberg (Charles Hazelius) Papers". Online Archive of California. San Diego Natural History Museum. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ Sternberg, Charles Hazelius (1909). The Life of a Fossil Hunter. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780722249024.

- ^ Sternberg, Charles Hazelius (1917). Hunting Dinosaurs in the Badlands of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada. Lawrence, Kansas.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sternberg, Charles Hazelius (1911). A Story of the Past: or, The Romance of Science. Boston: Sherman, French & Company.

- ^ Rogers, Ed (2013). "Rare Paleontology Book, Charles H. Sternberg; A Story of the Past". Ed Rogers Rare and Out of Print Geology Books. Ed Rogers Geology Books. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Preston, Douglas J. (1986). Dinosaurs in the Attic - An Excursion into the American Museum of Natural History. New York: St Martin's Press.

- ^ Sawyer, Robert J. (1994). End of an Era. New York: TOR. p. 21. ISBN 0-312-87693-9.

- ^ Bowling, Tim (2007). The Bone Sharps. Kentville, Nova Scotia: Gaspereau Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-55447-035-8.

- ^ Crichton, Michael (2017). Dragon Teeth: A Novel. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-247335-6.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Charles Hazelius Sternberg at the Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Hazelius Sternberg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Class materials on the Sternbergs from a History of Geology course". Emporia State University.

- "Sternberg Museum of Natural History". fhsu.edu. Hays, Kansas. Archived from the original on October 25, 2005.

- "Trip to Hays, Sternberg Museum". Washburn.edu.

- "Charles H. Sternberg". Oceans of Kansas Paleontology.

- "Charles H. Sternberg, Fossil Collector". Flickr, San Diego Natural History Museum Research Library. October 15, 2019.