Stagodontidae

| Stagodontidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Didelphodon skull diagram | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | †Archimetatheria |

| Family: | †Stagodontidae Marsh, 1889 |

| Genera | |

|

†Didelphodon | |

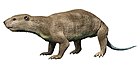

Stagodontidae is an extinct family of carnivorous metatherian mammals that inhabited North America and Europe[3] during the late Cretaceous,[1] and possibly to the Eocene in South America.

Description

[edit]Currently, the family includes four genera, Eodelphis, Didelphodon, Fumodelphodon and Hoodootherium, which together include some seven different species.[1][2] In addition, the Cenomanian species Pariadens kirklandi might be a member of the family.[2] Carneiro and Oliveira (2017) considered the species Eobrasilia coutoi from the early Eocene (Itaboraian) of Brazil to be a stagodontid;[4] if confirmed it would make it the only known Cenozoic and the only known South American member of the family. Stagodontids were some of the largest known Cretaceous mammals, ranging from 0.4 to 2.0 kilograms (0.88–4.41 lb) in mass.[5] One of the most unusual features of stagodontids are their robust, bulbous premolars, which are thought to have been used to crush freshwater mollusks,[6] a diet that apparently evolved independently at least twice within this clade.[7] Postcranial remains suggest that stagodontids may have been semi-aquatic.[8][9] The most well described forms are found in Laramidia, but they are also present on Appalachian and South American sites, further leading credence to their aquatic habits.[10] Cretaceous fossils were also found in France, suggesting a pan-Laurasian distribution for Cretaceous metatherians.[3]

The evolution of Didelphodon and other large stagodontids (as well as large deltatheroideans like Nanocuris) occurs after the local extinction of eutriconodont mammals, suggesting passive or direct ecological replacement.[11] They are considered rare in any given fauna they appear in, probably due to their specialised habits.[12]

Classification

[edit]Stagodontids were once thought to be closely related to the Sparassodonta, but later studies suggest they belong to a more ancient branch of the metatherian family tree, possibly closely related to pediomyids,[13][14] being in particular closest to Pariadens, which forms the immediate outgroup to Stagodontidae.[15][16] With the possible exception of Eobrasilia (see above), stagodontids are last known from the Maastrichtian, and are thought to have gone extinct in the K-T Extinction.

- Family Stagodontidae[1][2]

- Genus Didelphodon

- Didelphodon coyi

- Didelphodon padanicus

- Didelphodon vorax

- Genus Eodelphis

- Eodelphis browni

- Eodelphis cutleri

- Genus Fumodelphodon

- Fumodelphodon pulveris

- Genus Hoodootherium

- Hoodootherium praeceps

- Genus Didelphodon

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fox, Richard C.; Bruce G. Naylor (2003). "Stagodontid marsupials from the late Cretaceous of Canada and their systematic and functional implications". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 13–36.

- ^ a b c d Joshua E. Cohen (2018). "Earliest Divergence of Stagodontid (Mammalia: Marsupialiformes) Feeding Strategies from the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) of North America". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25 (2): 165–177. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9382-0. S2CID 18977109.

- ^ a b Vullo, Romain; Gheerbrant, Emmanuel; Beurel, Simon; Swajda, Michaël; Néraudeau, Didier (23 September 2020). "A stagodontid mammal from the mid-Cretaceous of France confirms the Euramerican distribution of early marsupialiforms". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 560: 110034. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110034.

- ^ Leonardo M. Carneiro; Édison Vicente de Oliveira (2017). "Systematic affinities of the extinct metatherian Eobrasilia coutoi Simpson, 1947, a South American Early Eocene Stagodontidae: implications for "Eobrasiliinae"". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 20 (3): 355–372. doi:10.4072/rbp.2017.3.07.

- ^ Gordon, Cynthia L. (2003). "A First Look at Estimating Body Size in Dentally Conservative Marsupials". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 10: 1–21. doi:10.1023/A:1025545023221. S2CID 24639293.

- ^ Lofgren, Donald L. (January 1992). "Upper premolar configuration of Didelphodon vorax (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Stagodontidae)". Journal of Paleontology. 66 (1): 162–164. doi:10.1017/S0022336000033576.

- ^ Leonardo M. Carneiro; Édison Vicente de Oliveira (2017). "Systematic affinities of the extinct metatherian Eobrasilia coutoi Simpson, 1947, a South American Early Eocene Stagodontidae: implications for "Eobrasiliinae"". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 20 (3): 355–372. doi:10.4072/rbp.2017.3.07.

- ^ "Didelphodon vorax". www.rmdrc.com. Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Chen, Meng; Wilson, Gregory P. (March 2015). "A multivariate approach to infer locomotor modes in Mesozoic mammals". Paleobiology. 41 (2): 280–312. doi:10.1017/pab.2014.14. S2CID 86087687.

- ^ Denton, R. K.; O’Neill, R. C. (October 2010). A New Stagodontid Metatherian from the Campanian of New Jersey and its implications for a lack of east-west dispersal routes in the Late Cretaceous of North America. 70th Anniversary Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. p. 81A.

- ^ G. W. Rougier, B. M. Davis, and M. J. Novacek. 2015. A deltatheroidan mammal from the Upper Cretaceous Baynshiree Formation, eastern Mongolia. Cretaceous Research 52:167-177

- ^ Leonardo M. Carneiro; Édison Vicente de Oliveira (2017). "Systematic affinities of the extinct metatherian Eobrasilia coutoi Simpson, 1947, a South American Early Eocene Stagodontidae: implications for "Eobrasiliinae"". Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 20 (3): 355–372. doi:10.4072/rbp.2017.3.07.

- ^ Marshall, L.; Case, J.; Woodburne, M. O. (1990). "Phylogenetic relationships of the families of marsupials". Current Mammalogy. 2: 433–505. S2CID 88876594.

- ^ Forasiepi, Analia M (2009). Osteology of Arctodictis sinclairi (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) and phylogeny of Cenozoic metatherian carnivores from South America. Monografias del Museo argentino de ciencias naturales. Vol. 6. Museo argentino de ciencias naturales. OCLC 875765668.

- ^ Rougier, Guillermo W.; Davis, Brian M.; Novacek, Michael J. (January 2015). "A deltatheroidan mammal from the Upper Cretaceous Baynshiree Formation, eastern Mongolia". Cretaceous Research. 52: 167–177. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.09.009.

- ^ Bi, Shundong; Jin, Xingsheng; Li, Shuo; Du, Tianming (14 April 2015). "A new Cretaceous Metatherian mammal from Henan, China". PeerJ. 3: e896. doi:10.7717/peerj.896. PMC 4400878. PMID 25893149.