Deer stones culture

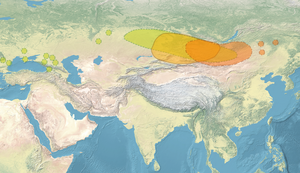

General location of the Deer stones, and contemporary Asian polities c. 1000 BCE. : Type I, : Type II, : Type III, and scattered individual finds. The three types can be found together in the area of western Mongolia.[1] | |

| Geographical range | South Siberia, Western Mongolia |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age, Early Iron Age |

| Dates | 1400 — 700 BCE[2] |

| Preceded by | Afanasievo Chemurchek culture Munkhkhairkhan culture Sagsai culture |

| Followed by | West: Arzhan, Chandman, Pazyryk culture East: Slab-grave culture |

Deer stones (Mongolian: Буган чулуун хөшөө), sometimes called the Deer stone-khirigsuur complex (DSKC) in reference to neighbouring khirigsuur tombs,[3] are ancient megaliths carved with symbols found mainly in Mongolia and, to a lesser extent, in the adjacent areas in Siberia. 1300 of 1500 the deer stones found so far are located in Mongolia. The name comes from their carved depictions of flying deer. The "Deer stones culture" relates to the lives and technologies of the late Bronze Age peoples associated with the deer stones complexes, as informed by archaeological finds, genetics and the content of deer stones art.[4]

The deer stones are part of a pastoral tradition of stone burial mounds and monumental constructions that appeared in Mongolia and neighbouring regions during the Bronze Age (ca. 3000–700 BCE). Various cultures occupied the area during this period and contributed to monumental stone constructions, starting with the Afanasievo culture, and continuing with the Okunev, Chemurchek, Munkhkhairkhan or Ulaanzuukh traditions.[5][6] The deer stones themselves belong to one of the latest traditions of monumental stones, from circa 1400 to 700 BCE (Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age), but precede the Slab grave culture.[2] The deer stones also immediately precede, and are often connected to, the early stages of the Saka culture (particularly the Arzhan, Chandman and Pazyryk cultures) in the area from the Altai to Western Mongolia.[7] Deer stone art is earlier than the earliest Scythian sites such as Arzhan by 300 to 500 years, and is considered as pre- or possibly proto-Scythian.[8]

The Deer stones culture seems to have been influenced by the contemporary Karasuk culture to the northwest, with which it shares characteristics, particularly in the area of weapon metallurgy.[9][10]

Construction

[edit]

) are generally located in the most productive, well-watered areas of the northern Mongolian steppe.[11][12]

) are generally located in the most productive, well-watered areas of the northern Mongolian steppe.[11][12]Although Mongolia is globally quite arid, deer stones are generally located in the most productive, well-watered areas of the northern Mongolian steppe, particularly in the north and the west of the country, where most of Mongolia's cultural development has always taken place.[11]

In Mongolia, deer stones are generally associated with khirigsuur burial mounds, and seem to be part of an integrated Late Bronze Age mortuary ceremonial dating to ca. 1200-700 BCE.[13] The amount of work necessary to build such numerous and massive stone structures suggests a complex hierarchical society, which appears for the first time in the steppes of Mongolia, but became the foundation for later nomadic states and empires.[14] The graves are quite shallow, so that human remains are poorly preserved, and artifacts are few to inexistent.[15][16]

Deer stones are usually constructed from granite or greenstone, depending on which is the most abundant in the surrounding area.[17] They have varying heights; most are over 3 feet (0.9 m) tall,[18] but some reach a height of 15 feet (4.6 m). The tops of the stones can be flat, round or smashed, suggesting that perhaps the original top had been deliberately destroyed. The stones usually have their "face" oriented towards the east.[15]

The carvings and designs were usually completed before the stone was erected, though some stones show signs of being carved in place.[2] The designs were pecked or ground into the stone surface. Deep-grooved cuts and right-angle surfaces indicate the presence of metal tools. Stone tools were used to smooth the harsh cuts of some designs.[18] Nearly all the stones were hand carved, but some unusual stones show signs that they could have been cut with a primitive type of mechanical drill.[2]

Distribution

[edit]Archaeologists have found more than 1,500 deer stones in Eurasia. Over 1,300 of them were recorded in the territory of modern Mongolia.[19] A few more scattered deer stones are found in a wider area, in Xinjiang,[20] and as far west as Kuban, Russia;[21] the Southern Bug in Ukraine; Dobruja, Bulgaria; and the Elbe, which flows through the Czech Republic and Germany.[22][23]

Types of stones

[edit]

Deer stones do not have any human remains attached to them, although Khirigsuur tombs are often found in somewhat close proximity in Mongolia. This suggests that the tombs functioned as cenotaph monuments for departed leaders, and that the bodies were buried elsewhere.[25]

There is no apparent evolutionary chronology for the design of the deer stones, which suggests an earlier and rather accomplished tradition already existed, probably on a perishable material such as wood.[26] Stone probably started being used when metal tools became available.[26] There is also no clear difference of chronology between the different types of deer stones (types I, II and III), which also often occur at the same places.[26] Some of the simpler designs, such as the Saian-Altai stones (Type II) are actually dated among the oldest deer stones (1300 BCE), together with the Mongolian designs (Type I).[27]

Most deer stones originally had an anthropomorphic intent, suggested by the general "pillar" shape, and reliefs or drawings depicting a belt loaded with tools and weapons, a shield in the stone's back, jewelry such as a necklace, earrings, and a symbolic or, rarely, a realistic face, sometimes topped with a hat. The front, if undisturbed, is always oriented towards the east.[28]

The stylistic "flying deers" on the surface of many deer stones may not just be decorative designs, but may actually represent the body tattoos of the specific individuals being depicted. This hypotheses has been reinforced by the discovery of extensive body tattoos of "flying deers" on the skin of individuals from the Pazyryk culture. Deer stones may just be a schematical but complete representation of the tattooed body of the deceased, together with his tools and weapons.[29]

Looking at the various implement and tools depicted on the deer stones, such as the horse implements, the recurved bow and the gorytus, it appears that the people who raised the stone were fully dependent on the horse for their lifestyles and warfare.[30]

V. V. Volkov, in his thirty years of research, classified three distinct types of deer stones.

Type I: Classic Mongolian

[edit]These stones are fairly detailed and more elegant in their depiction methods. They usually feature a belted warrior with a stylized flying red deer on his torso. This type of stone is most prominent in southern Siberia and northern Mongolia. This concentration suggests that these stones were the origin of the deer stone tradition, and further types both simplified and elaborated on these.[31] These deer stone are often associated with "Khirgisuur" burials.[32] These Khirgisuur burial sites belong to an earlier archaeological period, but were appropriated by deer stone builders.[33]

-

Deer stone, Khövsgöl Province, Mongolia

-

Close-up of the weapons at the bottom of the Khövsgöl deer stone

-

Deer stone with flying deers, a Type I characteristic. Ulaan Batur

Type II: Sayan-Altai

[edit]

The Sayan-Altai stones feature some of the West Asian-European markings, including free-floating, straight-legged animals, daggers and other tools. The appearance of deer motifs is markedly diminished, and those that do appear often do not emphasise the relationship between reindeer and flying. The Sayan-Altai stones can be sub-divided into two types:

- The Gorno-Altai stones have simple warrior motifs, displaying tools in the belt region of the stone. Reindeer motifs appear but are few. The deer stones of the Altai are regularly associated with the early Scythian Pazyryk culture.[7]

- The Sayan-Tuva stones are similar to the Gorno-Altai but contain fewer images of animals. No deer motifs are present. The artistic style is much simpler, often consisting of only belts, necklaces, earrings and faces. In Tuva, deer stones are associated with the wealthy Saka burials of Arzhan 1[37] and Arzhan 2.[38][39]

-

Type II: Sayan-Altai type

-

Sayan-Altai Deer stone with its four sides, Surtiin Denj, Bürentogtokh, Khövsgöl. National Museum of Mongolia

Type III: West Eurasian

[edit]These stones feature a central region of the stone, sectioned off by two horizontal lines or "belts". There are also "earring hoops", large circles, diagonal slashes in groups of two and three known as "faces", and "necklaces", collection of stone pits resembling their namesake.[40] A few monuments classified as "deer stones" have been found as far as the Ural, Crimea or even the Elbe river, in a Scythian context (600-300 BCE).[41]

Imagery

[edit]There are many common images that appear in deer stones, as well as a multitude of ways they are presented.[2]

Reindeer

[edit]Deers feature prominently in nearly all of the deer stones. They are likely the red deer or maral (Cervus elaphus sibericus).[42] Early stones have very simple images of reindeer, and as time progresses, the designs increase in detail. A gap of 500 years results in the appearance of the complicated flying reindeer depiction. Reindeer are depicted as flying through the air, rather than merely running on land. The anthropologist Piers Vitebsky has written, "The reindeer is depicted with its neck outstretched and its legs flung out fore and aft, as if not merely galloping but leaping through the air."[17] The antlers, sometimes appearing in pairs, have become extremely ornate, utilizing vast spiral designs that can encompass the entire deer. These antlers sometimes hold a sun disc or other sun-related image. Other artwork from the same period further emphasizes the connection between the reindeer and the sun, which is a very common association in Siberian shamanism. Tattoos on buried warriors contain deer, featuring antlers embellished with small birds' heads. This reindeer-sun-bird imagery perhaps symbolizes the shaman's spiritual transformation from the earth to the sky: the passage from earthly life to heavenly life. As these deer images also appear in warrior tattoos, it is possible that reindeer were believed to offer protection from dangerous forces.[18] Another theory is that the deer spirit served as a guide to assist the warrior soul to heaven.[31]

Other animals

[edit]

Particularly in the Sayan-Altai stones, a multitude of other animals are present in deer stone imagery. One can see depictions of tigers, pigs, cows, horse-like creatures, frogs and birds.[2] Unlike the reindeer, however, these animals are depicted in a more natural style. This lack of ornate detailing indicates the lack of supernatural importance of such animals, taking an obvious backseat against the reindeer.[31] The animals are often paired off with one another in confrontation, e.g. a tiger confronting a horse in a much more earthly activity.

Patterns

[edit]Chevron patterns crop up occasionally, usually in the upper regions of the stone. These patterns can be likened to military shields, suggesting the stones' connection to armed conflict. It has also been suggested that chevron patterns could be a shamanic emblem representing the skeleton.[18]

Human faces

[edit]

The top of the stones is generally rounded or flat, but often sculpted at an angle so that the higher side faces the east.[43] Human faces are a much rarer occurrence and are usually carved into the top of the stone, also facing east. The face is sometimes only depicted symbolically, with a few regular slash marks (//, ///).[44] The neck is generally adorned by a necklace, in the form of strings of beads, and large circular earrings are often depicted on the sides, an apparent Late Bronze Age fashion.[45] These faces seem to be carved with an open mouth, as though singing. This also suggests a religious/shamanistic connection of the deer stone, as vocal expression is a common and important theme in shamanism.[45]

Such depictions suggest burials around central figures, characteristic of rather organized and stratified pastoralist societies. Horse were buried together, as well as horse bits. The powerful nomadic leaders, leading large-scale organized nomadic groups, may have affected the late Shang and early Zhou dynasties of China to the south, and may have some connection with the infamous Xianyun of Chinese history.[46]

Human faces on deer stones sometimes appear as belonging to a Europoid type, with long faces, long noses and deeply carved close-set eyes.[47] Some figures appear hooded in Early Nomadic or Scytho-Siberian style.[47]

Weapons and tools

[edit]The leaders depicted in these deer Stones (dated to 1400-700 BCE) were equipped with weapons and instruments of war, such as swords, daggers, knives, shafted axes, quivers, fire starters, or curved rein holders for their chariots.[45] Weapons and tools can be seen throughout all the stones, though weapons make a stronger appearance in the Sayan-Altai stones.[2] Bows and daggers appear frequently, as well as typical Bronze-Age implements, such as fire-starters or chariot rein holders.[18] The appearance of these tools helps date the stones to the Bronze Age.

Deer stones weapons are generally derived from those of the contemporary Karasuk culture to the northwest, a well-known center for ancient metallurgy with influences as far as Shang dynasty China.[10][48]

Horses and chariots

[edit]

The earliest domesticated horses in Mongolia belong to the people of the Deer Stone culture.[51]

Although horses seem to have been central to the lifestyle of the deer stone builders, it is unclear if their horses were used for riding or for pulling carts. Actually, among all of the pictures available from the deer Stones, none represent a rider on a horse.[52] So far, the first evidence of horse riding in eastern Eurasia dates to the early 1st millennium BCE in the Altai Mountains, and uncontrovertible evidence in the form of horse saddles dates to 400 BCE only, from the Saka sites of the Pazyryk culture.[53] On the contrary, images of horse chariots appear on some of the deer Stone monuments from central Mongolia, including a two-horse and a four-horse vehicle.[52]

Various tools typical of chariot riding also appear in the drawing of the deer stones, such as rein holders.[54] Rein holders were designed to hold the reins in place to free the rider's hands, and were probably hung to the rider's waist.[55][56] They worked as rein hooks, attached at the belt, for "hands free" horse control while using weapons.[57][58]

Origin and purpose

[edit]

The origins of the art of the deer stones remain uncertain.[26] According to current data, the art of the deer stones could be indirectly derived from an un-preserved tradition of Karasuk-related cultures, with possible antecedents in the depiction of human figures in the Yamnaya culture culture of the Western Steppes in the 2nd-1st millennium BCE, such as the Kernosivsky idol.[65] Cimmerian stone stelae-Kurgan stelae may be part of the answer. The Siberian Okunev culture (2700-1800 BCE) also has a long tradition of totemic standing stones from the 3rd millennium BCE.

The original artistic impulse for the classical deer stones may have to be found in the animals of the northern Siberian ecosystem and their representations in petroglyphic art, as far as the Neolithic.[66] As explained by Jacobson:

The general reasoning . . . is straightforward: the animals which dominate the archaic Scytho-Siberia style are all animals of the northern forest or forest-steppe. Furthermore . . . the archaic nature of the early nomadic styles and images indicates not only a tradition of bone and wood carving but also a tradition of zoomorphic representation that goes back as far as the Siberian Neolithic. The particular combination of cervids (deer, elk, reindeer), felines (panthers and tigers), caprids . . . and birds-of-prey, evident in the early art of the Early Nomads and that of their immediate predecessors, depends upon the emergence of an artistic tradition among the hunting-dependent Bronze Age cultures of South Siberia and Mongolia.

— Jacobson 1993, quoted in Fitzhugh 2009.[67]

Globally, the Classical Mongolian type does appear to have been the first generation of deer stones, suggesting a pre-deer stone tradition before 1500 BCE, originating in the Siberian northern taiga forest. Deer stones culture then may have spread westward under the pressure of the Slab-grave culture, to meet with an early Scythian Altai tradition, where the Sayan-Altai style of deer stones then developed.[68]

Genetic profile

[edit]

Genetic analyses of individuals buried in Late Bronze Age (LBA) burial mounds associated with the Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSKC) in northern Mongolia, found that these individuals primarily derived from Khövsgöl LBA source (about 4-7% Sintashta and 93-96% Baikal EBA). The individuals were close to contemporary Neolithic and Bronze Age Baikal populations, and clustered "on top of modern Tuvinians or Altaians".[69][70]

The analysed individuals also included some outliers, with remains in westernmost Mongolia (also named Altai_MLBA) displaying a balanced West-East Eurasian ancestry, with about 45% Sintashta and 55% Baikal EBA, being virtually identical with that of the later Eastern Sakas, particularly from the Chandman culture (Chandman_IA), and remains with an increased Neolithic Amur genetic profile, displaying similarities with the Ulaanzuukh and Slab-grave culture to their East.[70][69]

The Ulaanzuukh culture, distinct from the "Deer stone culture", and corresponding to burials in Southeastern Mongolia, had a purely Northeast Asian profile (nearly 100% ANA), with one outlier having a western Altai_MLBA profile.[69]

Later cultures are known to have often reused the stones in their own burial mounds (known as kheregsüürs) and for other purposes.

Historiography

[edit]In 1892, V.V. Radlov published a collection of drawings of deer stones in Mongolia. Radlov's drawings showed the highly stylized images of deer on the stones, as well as the settings in which they were placed. Radlov showed that in some instances the stones were set in patterns suggesting the walls of a grave, and in other instances, the deer stones were set in elaborate circular patterns, suggesting use in rituals of unknown significance.[22]

In 1954 A.P. Okladnikov published a study of a deer stone found in 1856 by D.P. Davydov near modern Ulan-Ude now known as the Ivolga stone, displayed in the Irkutsk State Historical Museum. Okladinkov identified the deer images as reindeer, dated the stone's carving to the 6th-7th centuries BC, and concluded from its placement and other images that it was associated with funerary rituals, and was a monument to a warrior leader of high social prominence.[22]

An extensive 1981 study by V.V. Volkov identified two cultural conditions behind the deer stones. The eastern deer stones appear to be associated with cemeteries of the Slab Grave culture. The other cultural tradition is associated with the circular structures suggesting use as the center of rituals.[22]

There are several proposed theories for the purpose of the deer stones. There are different viewpoints about the origins of deer stone art. According to H.L. Chlyenova, the artistic deer image originated from the Saka tribe and its branches (Chlyenova 1962). Volkov believes that some of the methods of crafting deer stone art are closely related to Scythians (Volkov 1967).

Mongolian archaeologist D. Tseveendorj regards deer stone art as having originated in Mongolia during the Bronze Age and spread thereafter to Tuva and the Baikal area (Tseveendorj 1979).

D. G. Savinov (1994) and M. H. Mannai-Ool (1970) have also studied deer stone art and have reached other conclusions. The stones do not occur alone, usually with several other stone monuments, sometimes carved, sometimes not. The soil around these gatherings often contains traces of animal remains, for example, horses. Such remains were placed underneath these auxiliary stones. Human remains, on the other hand, were not found at any of the sites, which discredits the theory that the stones could function as gravestones.[18] The markings on the stones and the presence of sacrificial remains could suggest a religious purpose, perhaps a prime location for the occurrence of shamanistic rituals.[17]

Some stones include a circle at the top and stylised dagger and belt at the bottom, which has led some scholars, such as William Fitzhugh, to propose that the stones could represent a spiritualized human body, particularly that of a prominent figure such as a warrior or leader.[18] The decorative flying deers would actually be the tattoos on the body of the deceased, as seen with the tattoos of an ice mummy from Pazyryk.[72] This theory is reinforced by the fact that the stones are all very different in construction and imagery, which could be because each stone tells a unique story for the individual it represents.

In 2006, the Deer Stone Project of the Smithsonian Institution and Mongolian Academy of Sciences began to record the stones digitally with 3-D laser scanning.[73]

Legacy

[edit]Animal style

[edit]The artistic depictions of animals on deer Stones are the earliest recognized type of Animal style. This style would then spread across Central Asia during the 1st millennium BCE and become a characteristic feature of Scytho-Siberian art.[74] The spread of animal style and Sayan-Altai deer stones was supported by the westward migration of Scythian groups, which came to be known as Saka or Sarmatians in Greek records.[75]

To the southeast, the Upper Xiajiadian culture is considered as the earliest "Scythian" (Saka) culture in North China, starting the 9th century BCE.[76] The development of animal styles there may have been the result of contacts with the nomads of Mongolia in the 9th — 8th centuries BCE.[76]

Contemporary artifacts in western Mongolia

[edit]-

Bronze Age gold earrings, Burgastain gol, Uvs Province, Mongolia. National Museum of Mongolia

-

Bronze Age bronze bridle ornaments, 1200-800 BCE, National Museum of Mongolia

-

Stone mold for the casting of bronze objects, 1500-400 BCE, National Museum of Mongolia

Transmission of chariot warfare and weapon designs to China

[edit]

Chariots were used for a long time in Western Eurasia, and the development of the horse chariot in the deer Stone culture is an expansion of it, but it also probably impulsed the rise of the horse chariot in Shang dynasty China.[52] The area of the Mongolian plateau corresponding to the Deerstone-Khirigsuurs culture has been identified as a "major region of origin for chariot and horse use in East Asia (and their associated weapons and tools), and also the likely source for the chariots and horses employed at Anyang" (the Chinese Shang capital), contributing weapon technology and designs, as well as the horse chariot itself.[80] Rein holders first appear in China at Yinxu circa 1200 BCE, and were probably introduced in China from the Northern Zones.[55]

The adoption of the chariot in China is dated to circa 1200 BCE, at the time of the Shang Emperor Wu Ding.[81] Major conflicts with chariot-riding northern enemies, called Guifang ("Devil people") or Xianyun by the Chinese, are also reported around that time in Chinese inscriptions.[82]

Various other people probably contributed to the transfer of these technologies from the Mongolian steppe to Shang dynasty China, such as the people of Tevsh-Ulaanzuukh culture of southern Mongolia, who also had hand weapons broadly similar to those of the Deer stones culture.[12] Northern people were seemingly present in large number in the Chinese capital of Anyang, as suggested by the numerous burials in prone position together with charioting equipment. They were probably used by the Chinese for their specialist charioting skills and related warfare techniques.[83] Numerous Chinese artifacts in Northern Steppes style have been identified.[12]

The art of the deer stones may also have influenced Chinese art, particularly the sudden apparition of naturalism and animal themes during the Western Zhou (1045–771 BCE).[84]

-

Deer stone drawings of rein holders (left), and Chinese Shang dynasty bronze rein holder, ca. 11th century BCE (right).[85]

-

Deer stone drawing of a dagger and its scabbard (left), and Chinese Shang dynasty knife in Northern Steppe style (right).[12]

-

Jade standing deer (西周玉鹿), Western Zhou, 11-9th century BCE.[84]

-

Pendant in the form of a stag. Western Zhou dynasty, ca. 1050-ca. 950 BCE.[84]

Demise and legacy

[edit]

The "Deer stone culture" was replaced by the Slab-grave culture in central and eastern Mongolia around 700 BCE.[86] To the west, the "Deer stone culture" was replaced by, or evolved into, the various Saka cultures, such as the Uyuk culture, the Chandman culture, and the Pazyryk culture.[18]

While the majority of Slab Grave remains were of primarily Neolithic Amur ancestry, some Slab Grave remains displayed admixed ancestry between Neolithic Amur and pre-existing Khövsgöl/Baikal hunter-gatherers, consistent with the proposed expansion of Ulaanzuukh/Slab Grave ancestry north and westwards and archaeological evidence.[87]

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ Fitzhugh, William W. (1 March 2017). "Mongolian Deer Stones, European Menhirs, and Canadian Arctic Inuksuit: Collective Memory and the Function of Northern Monument Traditions". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 24 (1): Fig. 18. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9328-0. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 254605923.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fitzhugh 2009.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 183.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 73, "Because deer stone art illustrates many features of the lives and technology of these late Bronze Age peoples...".

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Taylor, William; Wilkin, Shevan; Wright, Joshua; Dee, Michael; Erdene, Myagmar; Clark, Julia; Tuvshinjargal, Tumurbaatar; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav; Fitzhugh, William; Boivin, Nicole (6 November 2019). "Radiocarbon dating and cultural dynamics across Mongolia's early pastoral transition". PLOS ONE. 14 (11): e0224241. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1424241T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224241. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6834239. PMID 31693700.

One rare source of empirically dateable material useful for understanding eastern Eurasia's pastoral tradition comes from the stone burial mounds and monumental constructions that began to appear across the landscape of Mongolia and adjacent regions during the Bronze Age (ca. 3000–700 BCE). Here, along with presenting 28 new radiocarbon dates from Mongolia's earliest pastoral monumental burials, we synthesise, critically analyse, and model existing dates to present the first precision Bayesian radiocarbon model for the emergence and geographic spread of Bronze Age monument and burial forms. Model results demonstrate a cultural succession between ambiguously dated Afanasievo, Chemurchek, and Munkhkhairkhan traditions. Geographic patterning reveals the existence of important cultural frontiers during the second millennium BCE.

- ^ a b Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, pp. 158–159, "Within the Altai region, despite one major, surviving coincidence of deer stones and khirgisuur (Tsagaan Asga), burial mounds of the early Scythian Pazyryk culture are the only monument type with which deer stones are regurlarly associated..

- ^ "The Mysterious Steles of Mongolia". CNRS News.

Nearly a thousand ornamented steles dot the Mongolian steppes. These "deer stones" were erected between 1200 and 800 BC, and are part of large funerary complexes built by nomads from the Karasuk culture or Deer stone civilisation.

- ^ a b Turbat, Tsagaan; J.Gantulga; N.Bayarkhuu; D.Batsukh; N.Turbayar; N.Erdene-Ochir; N.Batbold; Ts.Tselkhagarav (2021). Tsagaan Turbat (ed.). "Deer Stone Culture of Mongolia and Neighboring Regions". Institute of Archaeology, Mas & Institute for Mongol Studies, Num. Ulaanbaatar.

Weapons depicted on the Deer stones commonly found from the Mongolia and neighboring regions such as Southern Siberian Karasuk culture (13-8th centuries BCE) as well as Northern Chinese and Early Scythian graves (7th century BCE). (...) Based on relative chronology, MT type Deer stones belongs to the Karasuk period (13-8th centuries BCE) or according to new Siberian archaeology terminology (Polyakov 2019): to the Late Bronze Age period. A well-known example is that some emblematic objects of the Late Karasuk period were depicted on Deer stones. Moreover, the absolute dating of Deer stones and the Khirgisuur, the chronologically identical and directly related funeral-ritual structure to the former, were dated to the 13-8th centuries BCE as well.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 74, "His distribution map (Fig. 2) also showed that while deer stones are found beyond the boundaries of Mongolia they are concentrated in the most productive, well-watered region of the northern Mongolian steppe that has been the core area for Mongolian cultural development during the past four thousand years.".

- ^ a b c d e f Rawson 2020.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 183, "Often accompanied by stone burial mounds with fenced perimeters and satellite mounds, deer stones and khirigsuurs are interlinked components of a single Late Bronze Age mortuary ceremonial system dating to ca. 1200-700 BC.".

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, "Perhaps most important, the deer stone-khirigsuur complex represents for the first time in Mongolia the emergence of a complex hierarchical society that established the foundation for the formation of later nomadic states and empires.".

- ^ a b Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 189.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 74, "But when excavations revealed that neither khirigsuurs nor deer stones produced artifacts, archaeological work shifted to more productive sites.".

- ^ a b c Vitebsky, Piers (2011). Reindeer People: Living with Animals and Spirits in Siberia. Harper Perennial. p. 498.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fitzhugh 2009b, pp. 72–88.

- ^ Ж. Баярсайхан Монголын Умард нутгийн буган хөшөөд 2017 ISBN 978-99978-1-864-5

- ^ HATAKEYAMA, Tei (2002). "The Tumulus and Stag Stones at Shiebar-kul in Xinjiang, China". 草原考古通信. 13.

- ^ "Statues – "Deer stones" with photograph". nav.shm.ru. Moscow State National Museum.

- ^ a b c d Jacobson, Esther (1993). The deer goddess of ancient Siberia : a study in the ecology of belief. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09628-8.

- ^ Swendseid, Katrina (1 January 2018). "Turkic Stelae - Figures". Turkic Stelae of Central and Inner Asia: 6th - 13th Centuries C.E.

- ^ Török, Tibor (July 2023). "Integrating Linguistic, Archaeological and Genetic Perspectives Unfold the Origin of Ugrians". Genes. 14 (7): 1345. doi:10.3390/genes14071345. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 10379071.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, pp. 72–88, "The absence of any sign of human remains confirms that deer stones are not grave stones; most probably they are cenotaph monuments for dead leaders lost or buried elsewhere.".

- ^ a b c d Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 196.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 196, "To date there is no stylistic or chronological evidence suggesting a developmental sequence for either the simpler Saian-Altai or the classic Mongolian deer stone types. Given this rapid development it seems likely that deer stones and their art were transferred from an earlier medium, like wood, as suggested by K. Jettmar (1994), concurrent with introduction of metal tools. Although the Saian-Altai stones are numerically more common in Tuva and the Altai than the classic form, both frequently appear at the same sites and probably date to the same time. In Khovsgol, some Saian-Altai stones are among the earliest dated deer stones, ca. 1300 BC, and at one site we recently excavated in Khovsgol-Khyadag East -both types are associated with copper slag.".

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, p. 156, "Wherever they appear, most deer stones have an anthropomorphic shape or include elements that indicate the stone’s anthropomorphic reference, such as belts from which hang weapons and tools, a shield on the stone’s “back,” a necklace of beads, earrings, and parallel, diagonally placed slashes on the “face,” as if to indicate features. On a few rare occasions the stones are given a human visage, and some are embellished with what might be interpreted as a hat. Unless the stone has been twisted on its axis by time, the elements, or human intervention, it is always oriented so that the face is to the east and the back to the west.".

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 188, "Since the earliest interpretations by N. N. Dikov (1958), A. E. Novgorodova (Volkov/ Novgorodova 1975), and A. P. Okladnikov (1954), deer stones have been seen as stylized warriors. Following the discovery of tattooed bodies at Pazyryk (Rudenko 1970; Polos'mak 2000; Griaznov 1984) K.Jettmar (1994) proposed that the deer images might represent tattoos. Magail (2005) suggests clothing designs. I would go a step further and suggest the detailed rendering of belts, weapons, and tools reveal the artist's intent to carve deer stones as representations of specific individuals. The depictions seem to represent unique assemblages of tools, weapons, and body tattoos. One never finds deer stones with identical kinds, shapes, and sizes of implements, as would be the normal case in living individuals.".

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, p. 191, "On the other hand, those who raised the deer stones were fully horse dependent: this is made obvious by the implements and weapons pecked into the deer stones and most particularly by the recurved bow and gorytus..

- ^ a b c Fitzhugh, William (2009). "The Mongolian Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex: Dating and Organization of a Late Bronze Age Menagerie" (PDF). In J Bemmann; H Parzinger; E Pohl; D Tseveendorj (eds.). Current Archaeological Research in Mongolia. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat. pp. 183–199.

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, pp. 158–159, "However, some of the most impressive deer stone groupings, such as those at Ushkiin-Uver and Tsatsyn Ereg, are also found in the vicinity of khirgisuur. For that reason, it has become a rule of thumb among many archaeologists that deer stones belong together with khirgisuur in a single culture, one referred to as the “Deer Stone-Khirgisuur Complex” (DSK). (...) The cultural phenomenon denoted as the “Deer Stone-Khirgisuur Complex” has, for better or worse, become widely accepted, but primarily by reference to materials within the central Mongolian aimags. Within the Altai region, despite one major, surviving coincidence of deer stones and khirgisuur (Tsagaan Asga), burial mounds of the early Scythian Pazyryk culture are the only monument type with which deer stones are regularly associated. This fact suggests that it might be fair to test the validity of the DSK concept by what we can find in the Mongolian Altai and specifically in Bayan Ölgiy aimag.".

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, p. 191, "It is clear from the horse head sacrifices associated with khirgisuur that those who built those monuments kept horses for food, milk, traction, and load bearing; but there is no clear sign that these people were primarily horse riders. On the other hand, those who raised the deer stones were fully horse dependent: this is made obvious by the implements and weapons pecked into the deer stones and most particularly by the recurved bow and gorytus.Whether in Bayan Ölgiy or in the central aimags, the appearance of deer stones together with khirgisuur indicate that horsemen who raised the deer stones arrogated to their own purposes the older monuments, using them to assert their own cultural values.".

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, William W. (1 March 2017). "Mongolian Deer Stones, European Menhirs, and Canadian Arctic Inuksuit: Collective Memory and the Function of Northern Monument Traditions". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 24 (1): Fig. 9. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9328-0. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 254605923.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, Fig.4 (best quality reproduction).

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, pp. 183–184, Figure 7.25, "Figure 7.25 Stone with human face. Early Iron Age. Chuya river valley. Ongudai region, Altai Republic. View of east face. (...) A close parallel can be found in a tall deer stone in the Chuya river valley in southeastern Ongudai region (7.25). This stone has a clear if sunken face; a dagger and diminutive battle axe; and an inverted horse and recurved bow on its north side.".

- ^ Jacobson-Tepfer 2023, p. 160 Figure 7.2.

- ^ Pankova, Svetlana; Simpson, St John (1 January 2017). Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia. British Museum. pp. 28–30.

- ^ Fitzhugh, William W. (1 March 2017). "Mongolian Deer Stones, European Menhirs, and Canadian Arctic Inuksuit: Collective Memory and the Function of Northern Monument Traditions". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 24 (1): 149–187. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9328-0. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 254605923.

Type III ("Eurasian") stones, the simplest type, rarely display more than the minimal features of face slashes, earrings, and belt, usually without any animals, and occur in the Altai and sometimes as far west as the Pontic region and even in Eastern Europe

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, "Monuments classified as deer stones are also found as far west as the Ural, Crimea, and Georgia, where they are associated with the Scythian cultural horizon (600-300 BC), while a few have even been reported from the Elbe River (Volkov 1995, 326).".

- ^ Fitzhugh, William W.; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav (2021). "Khyadag and Zunii Gol: Animal Art and the Bronze to Iron Age Transition in Northern Mongolia". Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History. 66 (3): 914. doi:10.21638/11701/spbu02.2021.313. S2CID 243971383.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 77, "Their tops may be rounded or flat but more frequently angle up toward the east. Features are pecked or ground into the surface of the stone.".

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 77, "Their tops may be rounded or flat but more frequently angle up toward the east. Features are pecked or ground into the surface of the stone. In rare instances the head area shows a full human face which always faces east toward the rising sun, but often is signified only by two or three slash marks (//, ///) and is separated from the torso by an arcing series of shallow pits representing a beaded necklace. Ears are indicated on the south and north sides of the stone by circular hoops with dangling ornaments apparently depicting a common Late Bronze Age earring style.".

- ^ a b c Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 77.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (2015). "Steppe Weapons in Ancient China and the Role of Hand-to-hand Combat". 故宮學術季刊 (The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly). 33 (1): 59–60.

We can look first at Mongolia to explain this shift, for a new development, the creation of large stone monuments, khirigsuurs (fig. 19) and deer stones (fig. 20), marks significant on-going changes in steppe societies. These impressive structures are widespread across western and central Mongolia, dating from 1400-700 BC. It would have taken a large labour force to create the mounds of stones that make up khirigsuurs, which seem to have been both burial and ceremonial sites for central figures of the many small groups of Mongolian mobile pastoralist societies. (...) In some tombs are horse fittings, such as bits. Parts of hundreds of horses might be interred over time around a major khirigsuur. (...) Deer stones tell the same story (fig 20). Although the majority are stylised, a few of these tall, originally standing, stones have a human head carved on one side at the rounded top, sometimes with temple rings shown on two of the other three sides, perhaps representing a powerful individual, or the more general concept of powerful leaders. (...) Then comes a horizontal belt and from this hang weapons, especially knives or daggers, and shafted axes, with curved rein holders below. A shield is often shown higher up. Not only do these deer stones represent people, they memorialise the achievements of warriors with their personal weapons. (...) These developments had probably had an impact on the peoples in the arc who had then interacted with the late Shang and early Zhou states.

- ^ a b Jacobson, Esther (1 January 1993). "Deer Stones and Warriors: Anthropomorphic Monoliths of the First Millennium B.C." The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia. Brill: 150–151. doi:10.1163/9789004378780_007.

Among the deer stones of Gorno-Altayskaya A.O., as among those of Mongolia, a few are carved with clearly anthropomorphic references. (...) On its upper east side a distinctive face marks the flat surface of the stone. With a large long face, long nose, a mouth down-turned at one end, and close-set eyes carved deeply into the stone the face far more readily recalls a Europoid type than do the usual faces on Turkic stones of the Altay region (cf. Kubarev 1984). On the north-east side of the shaft a dagger is carved, while on the north side an image of a horse and of another large object, perhaps a bow, are carved. (...) The cowl-like treatment of the stone on the larger Iya figure suggests the hoods worn by Early Nomadic horsemen and by their Scytho-Siberian cousins across the Eurasian Steppe.

- ^ Jacobson, Esther (1 January 1993). "Deer Stones and Warriors: Anthropomorphic Monoliths of the First Millennium B.C." The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia. Brill: 153. doi:10.1163/9789004378780_007.

Although the weapons represented on the Mongolian stones are Karasuk in typology...

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, William W. (1 March 2017). "Mongolian Deer Stones, European Menhirs, and Canadian Arctic Inuksuit: Collective Memory and the Function of Northern Monument Traditions". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 24 (1): 165, Figure 14. doi:10.1007/s10816-017-9328-0. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 254605923.

- ^ a b Magail, Jérôme (2005). "Les "pierres à cerfs" des vallées Hunuy et Tamir en Mongolie". Bulletin du Musée d'Anthropologie préhistorique de Monaco: 49.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2021, p. 3, "The earliest domestic horses so far identified in Mongolia, however, belong to the Bronze Age Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex (DSK), which emerged towards the end of the second millennium BC. This culture is named for its ritual standing stones (deer stones) and burial mounds (khirigsuurs) that are often surrounded by multiple horse burial features (Fitzhugh 2009). DSK sites have yielded evidence for the ritual sacrifice and dietary exploitation of horses (Fitzhugh 2009), while skeletal changes indicate that DSK horses were bridled and heavily exerted, and received sophisticated veterinary care (Taylor et al. 2015, 2018). The co-occurrence of the first DSK horses with the appearance of domestic horses at late Shang Dynasty sites in China suggests that these two processes were linked (Honeychurch 2015).".

- ^ a b c Taylor et al. 2021, p. 3.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2021, p. 3, "Only chariots, not riders, are depicted on Mongolian deer stone carvings (Figure 1). Images of DSK horse-drawn vehicles depict a light, two-horse chariot with a platform situated over a central axle, with two animals under yoke (Figure 1: right) and, in one case, additional animals along the outside (Figure 1: middle).".

- ^ a b Yang, Jianhua; Shao, Huiqiu; Pan, Ling (3 January 2020). The Metal Road of the Eastern Eurasian Steppe: The Formation of the Xiongnu Confederation and the Silk Road. Springer Nature. p. 205. ISBN 978-981-329-155-3.

a rein-holder used to free the rider's hands

- ^ Teng, Mingyu (1 January 2012). "Also on the typology of bow-shaped objects and relevant issues". Chinese Archaeology. 12 (1): 132–133. doi:10.1515/char-2012-0016. S2CID 134585106.

- ^ Rawson, Huan & Taylor 2021, "curved hooks thought to have functioned as rein-holders for horse control, hanging from a belt around the stones".

- ^ Communications And The Earliest Wheeled Transport of Eurasia. 2012. p. 274.

The two-looped buckles (so-called «models of the yoke») for managing a vehicle, a kind of "hands free" for a charioteer, - and of various weapons for distant battles (bows and arrows) and the melee (axes, battle-axes, chisels, akinak-daggers), which describes the complete set of warriors-charioteers. It is noteworthy that all of the above items were attached variedly to a charioteer's belt and many times repeated on deer stones in various combinations. From a practical point of view, as noted above, attaching charioteer reins to own belt considerably expanded the charioteer's military capacity and allow to do without a driver.

- ^ Actual 2-horse chariot with photograph: Page 6

- ^ Communications And The Earliest Wheeled Transport of Eurasia. 2012. p. 273.

- ^ Taylor et al. 2021.

- ^ Esin, Yury; Magail, Jerome; Gantulga, Jamyian-Ombo; Yeruul-Erdene, Chimiddorj (1 September 2021). "Chariots in the Bronze Age of Central Mongolia based on the materials from the Khoid Tamir river valley". Archaeological Research in Asia. 27. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2021.100304. ISSN 2352-2267.

- ^ Wang, Chuan-Chao; et al. (2021). "Genomic Insights into the Formation of Human Populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419. Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. PMC 7993749. PMID 33618348.

- ^ Taylor, William Timothy Treal; Clark, Julia; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav; Tuvshinjargal, Tumurbaatar; Jobe, Jessica Thompson; Fitzhugh, William; Kortum, Richard; Spengler, Robert N.; Shnaider, Svetlana; Seersholm, Frederik Valeur; Hart, Isaac; Case, Nicholas; Wilkin, Shevan; Hendy, Jessica; Thuering, Ulrike; Miller, Bryan; Miller, Alicia R. Ventresca; Picin, Andrea; Vanwezer, Nils; Irmer, Franziska; Brown, Samantha; Abdykanova, Aida; Shultz, Daniel R.; Pham, Victoria; Bunce, Michael; Douka, Katerina; Jones, Emily Lena; Boivin, Nicole (22 January 2020). "Early Pastoral Economies and Herding Transitions in Eastern Eurasia". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1001. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.1001T. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57735-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6976682. PMID 31969593.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh 2009b, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Jeong et al. 2020, p. Figure 3C, 4A.

- ^ a b Jeong, Choongwon; Wilkin, Shevan; Amgalantugs, Tsend; Warinner, Christina (2018). "Bronze Age population dynamics and the rise of dairy pastoralism on the eastern Eurasian steppe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (48). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America: E11248–E11255. Bibcode:2018PNAS..11511248J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813608115. PMC 6275519. PMID 30397125. S2CID 53230942.

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 188: "Since the earliest interpretations by N. N. Dikov (1958), A. E. Novgorodova (Volkov/Novgorodova 1975), and A. P. Okladnikov (1954), deer stones have been seen as stylized warriors. Following the discovery of tattooed bodies at Pazyryk (Rudenko 1970; Polos'mak 2000; Griaznov 1984) K.Jettmar (1994) proposed that the deer images might represent tattoos. Magail (2005) suggests clothing designs. I would go a step further and suggest the detailed rendering of belts, weapons, and tools reveal the artist's intent to carve deer stones as representations of specific individuals. The depictions seem to represent unique assemblages of tools, weapons, and body tattoos. One never finds deer stones with identical kinds, shapes, and sizes of implements, as would be the normal case in living individuals. In like fashion, the images of deer also vary from stone to stone. While the shape of the deer icon is very rigidly standardized, their number, sizes, and placement varies in every case, as probably also occurred with tattoos on a person's body according to wealth, social status, prowess, or other attributes, including an artist's skills and the desires of the subject. It is likely that these tattoos protected the wearer from harm or injury by malevolent spirits in the same way as designs on the clothing of historic Ainu, Nivkh, and other East Asian groups. Patterns on the clothing of Jomon ceramic figurines may have had the same purpose. While serving as protective devices in life, the deer spirit may also have assisted the warrior's departed soul on its journey to heaven, with the help of shamanic ritual."

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009a, p. 188.

- ^ "The Mongolian-Smithsonian Deer Stone Project (DSP)". Smithsonian Global. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Taylor, William Timothy Treal (22 January 2020). "Early Pastoral Economies and Herding Transitions in Eastern Eurasia". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1001. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.1001T. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57735-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6976682. PMID 31969593. S2CID 210843957.

Deer Stones are recognized as the earliest clear progenitor for 'animal-style' art, a style that spread across most of Central Asia during the first millennium BCE

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, p. 81, "Deer stones are believed to have spread into the western Asia and the Pontic regions where Scythian groups settled as Saka, Sarmatian, and others described by Herodotus. These deer stones are not the classic Mongolian form with flying deer images and are similar to the simpler Sayan-Altai stones.".

- ^ a b Shulga, P.I. (2020). "THE CULTURES OF THE EARLY IRON AGE IN CHINA AS A PART OF THE SCYTHIAN WORLD". МАИАСП. 12: 119.

The materials analysis makes it possible to trace the Scythian cultures in North China formation and transformation process. The earliest is the "Xiajiadian upper layer" culture. Its representative monuments date back to the 9th — first half of the 7th centuries BCE. At that time the population in its area was in close contact with the Yan kingdom and neighboring cultures. Presumably, as a result of contacts with the Mongolia nomads in 9th — 8th centuries BCE, already established distinctive animal style images were spreading in the art of culture. By the middle of the 7th century BCE the "Xiajiadian upper layer" culture population part and nomadic Mongoloid tribes from Mongolia moved 150—250 km west to the Chinese kingdom of Yan northern border, where they mixed and settled.

- ^ "Ancient Mongolia". Google Arts & Culture. The National Museum of Mongolia.

- ^ "Shang knife British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

In subsequent centuries such knives were more popular with peoples of the northern zone than with the Shang and Zhou inhabitants of Shaanxi and Henan. It is, therefore, possible that even in the Erlitou period such knives illustrate contact with northern peoples. Alternatively, the spread of Erligang culture may have taken such knives from central Henan to the periphery.

- ^ So, Jenny F.; Bunker, Emma C. (1995). Traders and raiders on China's northern frontier: 19 November 1995 - 2 September 1996, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (PDF). Seattle: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Inst. [u.a.] pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0295974736.

Enough northern bronze knives, tools, and fittings have been recovered from royal burials at the Shang capital of Anyang to suggest that people of northern heritage mingled with the Chinese in their capital city. These artifacts must have entered Shang domain through trade, war, intermarriage, or other circumstances.

- ^ Rawson 2020, "These different monuments, petroglyphs, khirigsuurs and deer stones have illuminated the key role of the Mongolia plateau as a major region of origin for chariot and horse use in East Asia (and their associated weapons and tools), and also the likely source for the chariots and horses employed at Anyang".

- ^ Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1988). "Historical Perspectives on The Introduction of The Chariot Into China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 48 (1): 189–237. doi:10.2307/2719276. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2719276.

From this we might suggest an upper limit for artifactual evidence of the chariot in China of about 1200 B.C., which corresponds to the last part of King Wu Ding's reign (c. 1200-1180 B.C.).

- ^ Edward Shaughnessy, in Loewe and Shaughnessy, eds., Cambridge History of Ancient China, 1999, p.320ff, in Minford, John (2009). "The Triumph: A Heritage of Sorts". CHINA HERITAGE QUARTERLY China Heritage Project, China Heritage Quarterly. The Australian National University. 19.

- ^ Rawson 2020, "The people buried prone at Anyang were among several distinctive groups making up wider Shang society. This heterogeneity was inevitable as the Shang defended their territory and engaged with neighbouring peoples, but also because they sought resources from the north, such as horses, chariots and their drivers, as well as ores from the south." (...) "Thus, we argue that late Shang prone burials illustrate the diversity of the communities at Anyang. Among these were northerners who acted as chariot drivers, soldiers and leaders employed by the Shang to defeat other northerners. Some of the northern weapons found in Shang burials were brought from the north. Others were copies or Shang versions made and developed at Anyang to complement the identity and roles of their owners. The use of chariots and of a distinctive tool set in northern style indicates the close connections that the late Shang had with their northern neighbours.".

- ^ a b c Jacobson, Esther (1988). "BEYOND THE FRONTIER: A Reconsideration of Cultural Interchange Between China and the Early Nomads". Early China. 13: 222. doi:10.1017/S0362502800005253. ISSN 0362-5028. JSTOR 23351326. S2CID 162947097.

The deer stones of South Siberia and northern Mongolia indicate the continuity of imagery from the earlier petroglyphic tradition into the age of the early nomads. They also document the increasing stylization that emerged in certain parts of that nomadic world. This same petroglyphic tradition makes clear that naturalism continued to exist side-by-side with stylization, a combination that is also documented in bronze, gold, and wooden objects found in early nomadic burials. Given this long nomadic tradition of naturalistic rendition of wild animals and the fact that naturalism appears in Chinese art suddenly and combined with a very specific set of elements (e.g., rope patterns, animal combat themes, inlay), it seems probable that the Chinese adoption of naturalism was catalyzed by the same sophisticated taste that allowed Zhou artists to readopt and immediately adapt the use of stone inlay. To say that the nomads influenced Chinese naturalism is to infer a conscious exertion of priority where it did not exist. It probably brings us closer to the mark to say that the Chinese saw certain decorative possibilities, liked what they saw, and proceeded to borrow and change as quickly as they could.

- ^ Rawson 2020, "Charriot rein holders and northern knives and tools were recognized by Loehr (1956) and Watson (1971) as following prototypes known from South Siberia and Mongolia"....

- ^ Fitzhugh 2009b, pp. 80–81, "Both Russian and Mongolian dates suggest that slab burial appearance is time-transgressive northeast-to-southwest.".

- ^ Lee, Juhyeon; Miller, Bryan K.; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav; Johannesson, Erik; Ventresca Miller, Alicia; Warinner, Christina; Jeong, Choongwon (14 April 2023). "Genetic population structure of the Xiongnu Empire at imperial and local scales". Science Advances. 9 (15): eadf3904. Bibcode:2023SciA....9F3904L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf3904. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 10104459. PMID 37058560.

Likely arising out of the LBA Ulaanzuukh archaeological culture (ca. 1450 to 1150 BCE) in eastern Mongolia, Slab Grave groups expanded into central and northern Mongolia as far north as the Lake Baikal region (7, 14, 64). Overall, individuals from the Ulaanzuukh and the Slab Grave cultures present a homogeneous genetic profile that has deep roots in the region and is referred to as Ancient Northeast Asian (ANA) (14). ... This pattern, in which most Slab Grave individuals are genetically homogeneous while some have a large and heterogeneous ancestry fraction deriving from a Khovsgol_LBA-like gene pool, is likely due to population mixing in their recent past and is consistent with archaeological evidence that the Slab Grave culture expanded into central and northern Mongolia and replaced the preceding inhabitants in the region with a low level of mixing (65).

- ^ Gantulga, Jamiyan-Ombo (21 November 2020). "Ties between steppe and peninsula: Comparative perspective of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Мongolia and Кorea". Proceedings of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences: 65–88. doi:10.5564/pmas.v60i4.1507. ISSN 2312-2994. S2CID 234540665.

Sources

[edit]- Jeong, Choongwon; Wang, Ke; Wilkin, Shevan; Taylor, William Timothy Treal; Miller, Bryan K.; Bemmann, Jan H.; Stahl, Raphaela; Chiovelli, Chelsea; Knolle, Florian; Ulziibayar, Sodnom; Khatanbaatar, Dorjpurev; Erdenebaatar, Diimaajav; Erdenebat, Ulambayar; Ochir, Ayudai; Ankhsanaa, Ganbold; Vanchigdash, Chuluunkhuu; Ochir, Battuga; Munkhbayar, Chuluunbat; Tumen, Dashzeveg; Kovalev, Alexey; Kradin, Nikolay; Bazarov, Bilikto A.; Miyagashev, Denis A.; Konovalov, Prokopiy B.; Zhambaltarova, Elena; Miller, Alicia Ventresca; Haak, Wolfgang; Schiffels, Stephan; Krause, Johannes; Boivin, Nicole; Erdene, Myagmar; Hendy, Jessica; Warinner, Christina (12 November 2020). "A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia's Eastern Steppe". Cell. 183 (4): 890–904.e29. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 7664836. PMID 33157037.

- Eric A. Powell - Mongolia (Archaeology magazine January/February 2006)

- Jacobson, Esther, The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia BRILL, 1993 ISBN 978-90-04-09628-8

- Masson, Vadim, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 1 Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1999 ISBN 9788120814073

- Cremin, Aedeen, Archaeologica: The World's Most Significant Sites and Cultural Treasures frances lincoln ltd, 2007 ISBN 978-0-7112-2822-1 p 236

- History of Civilizations of Central Asia UNESCO, 1992 ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2

- Jacobson-Tepfer, Esther (2023). "Deer Stones (pp.155–191)". Monumental Archaeology in the Mongolian Altai. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004541306_008. ISBN 978-90-04-54130-6.

- Magail Jérôme (2004).– Les « Pierres à cerfs » de Mongolie, cosmologie des pasteurs, chasseurs et guerriers des steppes du Ier millénaire avant notre ère. International Newsletter on Rock Art, Editor Dr Jean Clottes, n° 39, pp. 17–27. ISSN 1022-3282

- Magail Jérôme (2005a).– Les « Pierres à cerfs » de Mongolie. Arts asiatiques, revue du Musée national des Arts asiatiques –Guimet Archived 13 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, n° 60, pp. 172–180. ISSN 0004-3958

- Magail Jérôme (2005b).– Les « pierres à cerfs » des vallées Hunuy et Tamir en Mongolie, Bulletin du Musée d’Anthropologie préhistorique de Monaco, Monaco, n° 45, pp. 41–56. ISSN 0544-7631

- Magail Jérôme (2008).– Tsatsiin Ereg, site majeur du début du Ier millénaire en Mongolie. Bulletin du Musée d’Anthropologie préhistorique de Monaco Archived 2 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 48, pp. 107–120. ISSN 0544-7631

- Rawson, Jessica (June 2020). "Chariotry and Prone Burials: Reassessing Late Shang China's Relationship with Its Northern Neighbours". Journal of World Prehistory. 33 (2): 135–168. doi:10.1007/s10963-020-09142-4. S2CID 254751158.

- Rawson, Jessica; Huan, Limin; Taylor, William Timothy Treal (December 2021). "Seeking Horses: Allies, Clients and Exchanges in the Zhou Period (1045–221 BC)". Journal of World Prehistory. 34 (4): 489–530. doi:10.1007/s10963-021-09161-9. S2CID 245487356.

- Savinov D.G. : Савинов Д. Г. (1994).- Оленные камни в культуре кочевников Евразии. Санкт-Петербург, 209 с.

- Fitzhugh, William (2009a). "The Mongolian Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex: Dating and Organization of a Late Bronze Age Menagerie" (PDF). In J Bemmann; H Parzinger; E Pohl; D Tseveendorj (eds.). Current Archaeological Research in Mongolia. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat. pp. 183–199.

- Fitzhugh, W. W. (1 January 2009b). "Stone Shamans and Flying Deer of Northern Mongolia: Deer Goddess of Siberia or Chimera of the Steppe?". Arctic Anthropology. 46 (1–2): 72–88. doi:10.1353/arc.0.0025. ISSN 0066-6939. S2CID 55632271.

- Volkov,V.V. (1995). - Chapter 20 Early Nomads of Mongolia in Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age Edited by Davis-Kimball, J. et al. ISBN 1-885979-00-2

- Taylor, William T. T.; Cao, Jinping; Fan, Wenquan; Ma, Xiaolin; Hou, Yanfeng; Wang, Juan; Li, Yue; Zhang, Chengrui; Miton, Helena; Chechushkov, Igor; Bayarsaikhan, Jamsranjav; Cook, Robert; Jones, Emily L.; Mijiddorj, Enkhbayar; Odbaatar, Tserendorj; Bayandelger, Chinbold; Morrison, Barbara; Miller, Bryan (December 2021). "Understanding early horse transport in eastern Eurasia through analysis of equine dentition". Antiquity. 95 (384): 1478–1494. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.146. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 262646985.

- Volkov V.V. : Волков В.В. (1981).- Оленные камни Монголии. Улан-Батор.

- Volkov V.V. : Волков В.В. (2002).- Оленные камни Монголии. Москва.

![Type I: Classic Mongolian (Uushigiin Övör site, Deer Stone 14), with its four sides.[34][35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Anthropomorphic_deer_stone._Uushigiin_%C3%96v%C3%B6r_site%2C_Deer_Stone_14%2C_near_M%C3%B6r%C3%B6n%2C_northern_Mongolia.jpg/200px-Anthropomorphic_deer_stone._Uushigiin_%C3%96v%C3%B6r_site%2C_Deer_Stone_14%2C_near_M%C3%B6r%C3%B6n%2C_northern_Mongolia.jpg)

![Bronze Age knife, 1200-800 BCE, Khovd aimag, Mongolia. National Museum of Mongolia.[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Bronze_age_knife%2C_1200-800_BCE%2C_Mongolia.jpg/200px-Bronze_age_knife%2C_1200-800_BCE%2C_Mongolia.jpg)

![Shang war charriots at Yinxu. Their technology was introduced from the Deer stone culture.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/Shang_Chariot_Burial_04.jpg/150px-Shang_Chariot_Burial_04.jpg)

![Deer stone drawings of rein holders (left), and Chinese Shang dynasty bronze rein holder, ca. 11th century BCE (right).[85]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2e/Deer_stone_drawing_of_a_rein_holders%2C_and_Chinese_Shang_bronze_rein_holder%2C_ca._11th_century_BCE.jpg/150px-Deer_stone_drawing_of_a_rein_holders%2C_and_Chinese_Shang_bronze_rein_holder%2C_ca._11th_century_BCE.jpg)

![Deer stone drawing of a dagger and its scabbard (left), and Chinese Shang dynasty knife in Northern Steppe style (right).[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Deer_stone_dagger_vs_Shang_knife.png/113px-Deer_stone_dagger_vs_Shang_knife.png)

![Jade standing deer (西周玉鹿), Western Zhou, 11-9th century BCE.[84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e6/Standing_deer_%282%29%2C_Western_Zhou%2C_11-9th_century_BCE.jpg/117px-Standing_deer_%282%29%2C_Western_Zhou%2C_11-9th_century_BCE.jpg)

![Pendant in the form of a stag. Western Zhou dynasty, ca. 1050-ca. 950 BCE.[84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Pendant_in_the_form_of_a_stag.jpg/150px-Pendant_in_the_form_of_a_stag.jpg)