St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate

| St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate | |

|---|---|

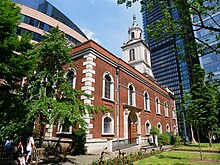

Exterior from Bishopsgate | |

| 51°31′0.15″N 0°4′53.96″W / 51.5167083°N 0.0816556°W | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England and Antiochian Orthodox Church |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | London |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | David Armstrong |

St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate is a Church of England church in the Bishopsgate Without area of the City of London, and also, by virtue of lying outside the city's (now demolished) eastern walls, part of London's East End.

Adjoining the buildings is a substantial churchyard – running along the back of Wormwood Street, the former course of London Wall – and a former school.[1] The church is linked with the Worshipful Company of Coopers and the Worshipful Company of Bowyers.

Position and dedication

[edit]The church lies on the west side of the road named Bishopsgate (Roman Ermine Street), near Liverpool Street station. The church and street both take their name from the 'Bishop's Gate' in London's defensive wall which stood approximately 30 metres to the south.

Stow, writing in 1598 describes the church of his time as standing "in a fair churchyard, adjoining to the town ditch, upon the very bank thereof".[2] The City Ditch was a defensive feature, that lay immediately outside the walls and was intended to make attack on the walls by mining or by escalade more difficult.

The church was one of four in medieval London dedicated to Saint Botolph or Botwulf, a 7th-century East Anglian saint, each of which stood by one of the gates to the city. The other three were near neighbour St Botolph's Aldgate, St Botolph's Aldersgate near the Barbican Centre and St Botolph's, Billingsgate by the riverside (this church was destroyed by the Great Fire and not rebuilt).[3]

By the end of the 11th century Botolph was regarded as the patron saint of boundaries, and by extension of trade and travel.[4] The veneration of Botolph was most pronounced before the legend of St Christopher became popular amongst travellers.[5]

It is believed[6] the church just outside Aldgate, 450 metres to the south-east, was the first in London to have been dedicated to Botolph, with the other dedications following soon after.

The Priory just inside Aldgate was founded by clergy from St Botolph's Priory in Colchester, just under fifty miles along the Roman Road from Aldgate. The Priory at Colchester, like the church at Aldgate (though not the Priory at Aldgate), lay just outside the South Gate (also known as St Botolph's Gate) in the Colchester's Wall. The Priors held the land of the Portsoken, outside the wall, and are thought to have built and dedicated the church, St Botolph without Aldgate, that served it.

The church of St Botolph's Church, Cambridge just outside the south gate of that city, may[original research?] in turn, have taken its dedication from St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate to which it was linked by Ermine Street.

History

[edit]The first known written record of the church is from 1212.[7] However, it is thought that Christian worship on this site may have Roman origins, though this is not fully proven.[8]

The church survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, and was rebuilt in 1724–29.

Middle ages

[edit]In around 1307, the Knights Templar were examined here by an inquisition on charges of corruption,[7] and in 1413 a female hermit was recorded as living here, supported by a pension of forty shillings a year paid by the Sheriff.[7]

It narrowly escaped the Great Fire of London, the sexton's house having been partly demolished to stop the spread of the flames.[9] Writing in 1708, Hatton described it as "an old church built of brick and stone, and rendered over". By this time the Gothic church had been altered with the addition of Tuscan columns supporting the roof, and Ionic ones the galleries.[2]

Present church

[edit]

In 1710, the parishioners petitioned Parliament for permission to rebuild the church on another site, but nothing was done.[10] In 1723 the church was found to be irreparable[9] and the parishioners petitioned again. Having obtained an act of Parliament, they set up a temporary building in the churchyard, and began to rebuild the church. The first stone was laid in 1725,[11] and the new building was consecrated in 1728, though not completed until the next year. The designer was James Gold[12] or Gould.[13] During construction, the foundations of the original Anglo-Saxon church were discovered.

To provide a striking frontage towards Bishopsgate, the architect placed the tower at the east end, its ground floor, with a pediment on the exterior, forming the chancel. The east end and tower are faced with stone, while the rest of the church is brick, with stone dressings.[12]

The interior is divided into nave and aisles by Composite columns, the nave being barrel vaulted. The church was soon found to be too dark, so a large west window was created, but this was largely obscured by the organ[12] installed in front of it in 1764.[9] In 1820 a lantern was added to the centre of the roof.[12]

The church was designated a Grade II* listed building on 4 January 1950[14] and contains memorials to the war dead of 5th and 8th Battalions London Regiment.

The church suffered minor bomb damage in the Second World War and subsequently in the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing.

Baptisms, marriages and burials

[edit]

The infant son of the playwright Ben Jonson is buried in the churchyard, and baptisms in this church include Edward Alleyn in 1566, Emilia Lanier (née Bassano; widely considered to be the first Englishwoman to become a professional poet) on 27 January 1569, and John Keats (in the present font) in 1795.[15] Emilia Lanier married Alfonso Lanier in the church on 18 October 1592.[16] Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was baptised there in 1759.[17]

At one point the satirist and essayist Stephen Gosson was rector. The didactic poet Robert Carliell (fl. 1619), who championed the new Church of England, held property in the parish.[18]

Church hall

[edit]

Within the churchyard, the church hall is the Grade II, former livery hall of the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers. It is a single-storied classical red brick and Portland stone building, with niches containing figures of charity children.[19]

The figures which stood in the niches at the front of the building were previously painted every year by schoolchildren, but have since been restored and stripped of paint and, due to theft attempts, moved inside the hall. Modern replicas now stand in the niches on the front of the building.[20]

Surroundings

[edit]

Also within the area of the church is the entrance kiosk to a former underground Victorian Turkish bath. It was designed by the architect, Harold Elphick, and opened by City of London Alderman Treloar on 5 February 1895 for Henry and James Forder Neville[a] who owned other Turkish baths[21] in Victorian London.

Rectors of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate

[edit]- —— John of Northampton

- 1323 Henry of Colne

- 1354 Richard of Pertenhale

- 1361 Robert Suardiby

- 1362 John of Bradeley

- 1363 Adam Keme

- 1365 Elias Finch

- 1368 Robert Fox

- 1370 Thomas de Boghee

- 1378 Thomas Ridilyngton

- 1379 John Grafton

- 1383 John Rydel

- —— John Bolton

- 1390 John Porter

- 1395 John Campeden

- 1398 John Gray

- 1399 Roger Mason

- 1404 John Philipp

- —— John Saxton

- 1433 Robert Coventre

- —— John Wood (as Archdeacon of Middlesex)[22]

- 1461 Thomas Knight (as Bishop of Down and Connor)

- 1468 John Prese

- 1471 Thomas Boteler

- 1472 Robert Keyvell

- 1482 John Pykyng

- 1490 Richard Sturton

- 1492 Clement Collins

- 1492 William London[23]

- 1503 Robert Ayschum

- —— Brian Darley[24]

- 1512–1515† Robert Woodward (or Woodruff)[25]

- 1515–1523† John Redman

- 1523–1524 Robert Ridley[26]

- 1524–1525† John Garth

- 1525–1534 Richard Sparchforth

- 1534–1541† Simon Matthew[27]

- 1541–1544† Robert Hygdon (or Higden)[28]

- 1544–1558† Hugh Weston (as Dean of Westminster 1553, Dean of Windsor 1556)

- 1558–1569 Edward Turner

- 1569–1584† Thomas Simpson

- 1584–1590 William Hutchinson (as Archdeacon of St Albans)

- 1590–1600 Arthur Bright[29]

- 1600–1624† Stephen Gosson

- 1624–1639† Thomas Worrall[30]

- 1639–1642 Thomas Wykes

- 1642–1660† Nehemiah Rogers (sequestered c. 1643)[31]

- 1660–1662 Robert Pory (as Archdeacon of Middlesex)

- 1663–1670 John Lake

- 1670–1677 Henry Bagshaw

- 1677–1678 Robert Clarke

- 1678–1687† Thomas Pittis[32]

- 1688–1701 Zacheus Isham

- 1701–1730† Roger Altham (as Archdeacon of Middlesex 1717)

- 1730–1743† William Crowe[33]

- 1743–1752 William Gibson (as Archdeacon of Essex 1747)

- 1752–1775† Thomas Ashton

- 1776–1815† William Conybeare

- 1815–1820 Richard Mant

- 1820–1828 Charles James Blomfield (as Archd. of Colchester 1822, Bishop of Chester 1824)

- 1828–1832 Edward Grey (as Dean of Hereford 1830)

- 1832–1863† John Russell

- 1863–1896† William Rogers

- 1896–1900 Alfred Earle (as Bishop of Marlborough)

- 1900–1911 Frederick Ridgeway (as Bishop of Kensington 1901)

- 1912–1935 G. W. Hudson Shaw

- 1935–1942 Bertram Simpson (as Bishop of Kensington)

- 1942–1950 Michael Gresford Jones (as Bishop of Willesden)

- 1950–1954 Gerald Ellison (as Bishop of Willesden)

- 1954–1961 Hubert H. Treacher

- 1961–1978 Stanley Moore

- 1978–1997 Alan Tanner

- 1997–2006 David Paton

- 2007–2015 Alan McCormack

- 2018–present David Armstrong

† Rector died in post

Notes

[edit]- ^ They dropped the final e of their surname when naming their baths.

References

[edit]- ^ Betjeman, John (1967). The City of London Churches. Andover: Pitkin. ISBN 0-85372-565-9.

(rpnt 1992)

- ^ a b Pearce, C.W. (1909). Notes on Old City Churches: their organs, organists and musical associations. London: Winthrop Rogers.

- ^ Daniell, A.E. (1896). London City Churches. London: Constable. p. 317.

- ^ Churches in the Landscape, p217-221, Richard Morris, ISBN 0-460-04509-1

- ^ Richardsn, John (2001) The Annals of London: A Year-by-year Record of a Thousand Years of History, W&N, ISBN 978-1841881355 (p. 16)

- ^ London 800-126, Brooke and Keir, p146

- ^ a b c Hibbert, C; Weinreb, D; Keay, J (1983). The London Encyclopaedia. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

(rev 1993, 2008)

- ^ "History of the Building". Parish and Ward Church St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Malcolm, James Peller (1803). Londinium Redivivium, or, an Ancient History and Modern Description of London. Vol. 1. London. p. 334.

- ^ "The City of London Churches: monuments of another age" Quantrill, E; Quantrill, M p102: London; Quartet; 1975

- ^ "The City Churches" Tabor, M. p122:London; The Swarthmore Press Ltd; 1917

- ^ a b c d Godwin, George; John Britton (1839). "St Botolph's, Bishopsgate". The Churches of London: A History and Description of the Ecclesiastical Edifices of the Metropolis. London: C. Tilt. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Bradley, Simon; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998). London:the City Churches. The Buildings of England. London: Penguin Books. p. 38. ISBN 0-14-071100-7.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1064747)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Tucker, T (2006). The Visitors Guide to the City of London Churches. London: Friends of the City Churches. ISBN 0-9553945-0-3.

- ^ Page on Emilia Bassano by Peter Bassano, her "first cousin, twelve times removed" Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Gordon, Lyndall (2006). Vindication : a life of Mary Wollstonecraft (1st Harper Perennial ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 7. ISBN 0060957743.

- ^ Sidney Lee, "Carleill, Robert (fl. 1619)", rev. Reavley Gair (Oxford, UK: OUP, 2004) Retrieved 27 May 2017. Pay-walled.

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1359149)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ "At St Botolph's Hall". Spitalfields Life. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Turkish baths in Victorian London

- ^ "Wood, John (WT459J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "London, perhaps William (LNDN489-)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Darley, Brian (DRLY489B)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Woodruff, Robert (WDRF468R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Ridley, Robert (RDLY515R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Matthew, Simon (MTW513S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Higden, Robert (HGDN514R)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Bright, Arthur (BRT569A)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Worrall, Thomas (WRL624T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Smith, Charlotte Fell (1897). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Smith, Charlotte Fell (1896). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 45. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Cooper, Thompson (1888). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

External links

[edit]- Worshipful Company of Coopers

Media related to St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate at Wikimedia Commons