St Antony's College, Oxford

| St Antony's College | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Entrance to the old building at St Antony's College | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Arms: Or on a chevron between three tau crosses gules as many pierced mullets of the field. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Between Woodstock Road, Bevington Road, Church Walk, and Winchester Road | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′47″N 1°15′46″W / 51.763149°N 1.262903°W | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Full name | The Warden and Fellows of St Antony’s College in the University of Oxford | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Sancti Antonii | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Plus est en vous | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto in English | There is more in you | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1950 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Named for | St Antony of Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sister college | Wolfson College, Cambridge | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Warden | Roger Goodman | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | None | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 443 (2018/2019)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Visitor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Boat club | SABC | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||||||||||||

St Antony's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1950 as the result of the gift of French merchant Sir Antonin Besse of Aden, St Antony's specialises in international relations, economics, politics, and area studies relative to Europe, Russia, former Soviet states, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, Japan, China, and South and South East Asia.[3]

The college is located in North Oxford, with Woodstock Road to the west, Bevington Road to the south and Winchester Road to the east. St Antony's had a financial endowment of £55.1m as of 2021.[4] Formerly a men's college, it has been coeducational since 1962.[5]

History

[edit]St Antony's was founded in 1950 as the result of the gift of Sir Antonin Besse of Aden, a merchant of French descent.[citation needed]

In 1947, Besse was considering giving around £2 million to the University of Oxford to found a new college. Ultimately, on the advice of his solicitor, R Clyde, who had attended New College, Besse decided to go ahead with the plan and permitted Clyde to approach the university with the offer. The university was initially unreceptive to the offer, and recommended that Besse instead devote his funds to improving the finances of some of the poorer existing colleges. Eventually Besse acquiesced, contributing a total of £250,000 in varied amounts to the following colleges: Keble, Worcester, St Peter's, Wadham, Exeter, Pembroke, Lincoln and St Edmund Hall. After this large contribution, the university decided to reconsider Besse's offer to help found a new college and, recognising the need to provide for the growing number of postgraduate students coming to Oxford, gave the venture their blessing; and in 1948, Besse signed a deed of trust appointing the college's first trustees.[citation needed]

The attention of the university then turned to providing the new college, by then called St Antony's, with a permanent home. Ripon Hall was initially considered as a good option for a building in which to house the college, but its owners refused to sell, forcing the university to continue its search for premises. They looked at several properties in quick succession, including Youlbury, the Wytham Abbey estate, and Manchester College, which was known to be in financial difficulties and which might thus consider the sale of its 19th-century Mansfield Road buildings. None of these options proved tenable, and the college began to look elsewhere. It is said that Besse became very frustrated with the university and its apparent lack of interest in his project at this point, and almost gave up any hope of its completion. However the college finally acquired its current premises at 62 Woodstock Road in 1950.[citation needed]

The College first admitted students in Michaelmas Term 1950 and received its Royal Charter in 1953. A supplementary charter was granted in 1962 to allow the college to admit women as well as men, and in 1963 the College became a full member of the University of Oxford.[5] By 1952 the number of students at St Antony's had increased to 27 and by the end of the decade that number had risen to 260, amongst whom 34 different nationalities were represented. The college initially struggled due to a lack of funding, and in the late 1960s serious consideration was given to uniting St Antony's with All Souls College when All Souls announced its intention to take a more active role in the education of graduate students. The plan did not come to fruition; All Souls rejected the proposed federal nature of the combined institution, saying they would consider nothing less than a full merger, a proposal which St Antony's governing body did not support. St Antony's lack of funds was partly solved under the wardenship of William Deakin, who devoted himself to college fund-raising and secured a number of generous loans from the Ford and Volkswagen foundations. Financial difficulties led to the cancellation of a number of proposed physical developments at its site on Woodstock Road. Not until the 1990s was it feasible for the college to embark upon a new building programme; however, since then St Antony's has continued to expand and open new specialist centres for the pursuit of area studies. The college is now recognised as one of the world's foremost centres for such studies.[3] and houses centres for the study of Africa, Asia, Europe, Japan, Latin America, the Middle East and Russia and Eurasia.[citation needed]

From the beginning Besse had expressed his hope that the new college, which he intended to open to men "irrespective of origin, race or creed", would prove instrumental in improving international cooperation and intercultural understanding. The college soon announced its primary role as such: "to be a centre of advanced study and research in the fields of modern international history, philosophy, economics and politics and to provide an international centre within the University where graduate students from all over the world can live and work together in close contact with senior members of the University who are specialists in their fields". The college is still true to its founding principle, remaining one of the most international colleges of the university, and home to many of Oxford's region-specific study departments. This latter feature, combined with the wardenship of William Deakin and St Antony's reputation as a key centre for the study of Soviet affairs during the Cold War, led to rumours of links between the college and the British intelligence services; the author Leslie Woodhead wrote to this effect, describing the college as "a fitting gathering place for old spooks".[6]: 220 St Antony's became notorious in both the British and Russian press as a "spy college."[7] The character of Roy Bland from John le Carré's Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is said to have been a top specialist in Soviet satellite states educated at St Antony's, from where he was recruited by George Smiley.

The official annals of the university state that St Antony's was one of four colleges, along with All Souls, Nuffield and Christ Church, which made a concerted effort to establish external links. In St Antony's case, the college established wide-ranging connections with diplomats and foreign visitors; this is further commented on as having made the college "perhaps more significant than any other single development in Oxford's adjustment to the contemporary international academic environment".[8]

The college's name alludes to its founder, whose name, Antonin Besse, is derived from the same linguistic root. For a long time it was not made clear whether Anthony the Great or Anthony of Padua was the intended namesake. The matter was finally settled in 1961, when the college finally deemed Anthony the Great to be more the appropriate choice, due to his links to one of the college's prime areas of specialisation - the Middle and Near East. Despite this, the college's banner is flown each year on both saints' days as a matter of tradition, and a statue of the "wrong" Anthony, Anthony of Padua (distinguished by his holding of the Christ child), stands in the college's Hilda Besse Building.[citation needed]

Buildings and grounds

[edit]Main building

[edit]

The college's main building was built in the early Victorian era for the Society of the Holy and Undivided Trinity at the behest of Marian Rebecca Hughes, the first woman to take monastic vows within the Church of England since the reformation. The order commissioned Charles Buckeridge, a local architect of some renown, to design the convent buildings. After initially proposing a circular design based on the symbolism of the holy trinity, Buckeridge took to a more traditional approach and drew up the plans for what is now St Antony's main building some time before 1865. Whilst initially there were plans to enlarge the convent with a northerly extension, for which place was made in the building's design, further building never took place. The convent finally opened in November 1868.[citation needed]

The total cost of the initial build was eight thousand pounds, a considerable sum at that time. It is said that upon first seeing the convent's new premises, the architect William Butterfield commented that it was the 'best modern building in Oxford after my college', by which he meant Keble. St Antony's acquired the former convent in 1950 after it had been vacated by the convent and Halifax House, which had occupied the premises in the immediate post war period. The building's chapel, which was never consecrated and now houses the college library, was built in the years 1891–1894 to Buckeridge's original design. The three panel paintings round the apse of the former chapel are by Charles Edgar Buckeridge.[9] The main building's undercroft, now the Gulbenkian Reading Room, was initially used by the nuns as a refectory, a role it continued to play until the completion of the Hilda Besse building in 1970.[10]

1960s: The Hilda Besse Building

[edit]

After a number of ambitious schemes, one of which had been designed by Oscar Niemeyer, to enlarge the college in the 1960s fell through due to lack of funds, the college decided to concentrate its efforts in providing for the construction of a small extension and acquisition of neighbouring properties. The Hilda Besse Building (then known as New Building) was opened in 1970; this building still serves its original purpose in housing the college's dining hall, graduate common room, and buttery (college bar), as well as ancillary meeting rooms. The next major expansion of the college came in 1993 with the completion of a new building to house the Nissan Institute for Japanese Studies and the Bodleian Japanese Library, whilst additional accommodation was not supplied until the Founder's Building was opened to mark the millennium in the year 2000.[citation needed] The Wahba Dining Hall, the main dining hall for the college located on the first floor of the Hilda Besse Building, was also used as a filming location for The Amateur, a 2025 spy film starring Rami Malek.

2000s: The Gateway Buildings

[edit]In the early 21st century not much development took place until completion of the college's new Gateway Buildings in 2013, which provide a new main entrance to the college and form the east, and final, side of the college's first quadrangle.[11] The funding for this was gained in part by Foulath Hadid who, for his outstanding services to the college, was elected to an Honorary Fellowship in 2004, and the Hadid Room, the college's meeting room, was named in his honour.[12]

The Investcorp Building

[edit]

As part of its ongoing development programme, St Antony's commissioned the construction of a new centre for Middle Eastern Studies. The Middle East Centre, or Investcorp Building, was designed by the Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid; it broke ground on 30 January 2013[13] and was opened as the Investcorp Building on 26 May 2015.[14][15] The Guardian described it as a "writhing metallic slug that does its best to maul the two historic buildings between which its contorted body is slung".[16] It was awarded the Sir Hugh Casson Award in 2015 for the worst new building of the year.[16]

Student life and study

[edit]St Antony's College has some 450 students from over 66 nationalities; about half of the students have a first language other than English. Student interests are represented by an elected body, the Graduate Common Room (GCR) Executive,[17] which is elected on an annual basis at the end of Michaelmas Term.

Most college accommodation is located on site, with around 104 en-suite bedrooms provided in the Gateway and Founder's buildings. Further rooms are to be found in converted Victorian houses both on site or very close by.[citation needed]

The college is host to the St Antony's Late Bar, located on the ground floor of the award-winning Hilda Besse building[18] and serving students throughout the academic year. In addition to operating as a bar, it hosts numerous themed bops, culture/region/country nights, live music events (guest concerts, open-mic nights, Battle of the Bands), welfare/charity functions, various tastings and launch parties, among others. Recurring events include Halloqueen, USA Night, Latin Bop, Balkan Night, and the thrice-annual Drink the Bar Dry.[19]

Libraries and publications

[edit]

The Old Main Building - the former Holy Trinity Convent[20] which was built in the 1860s - houses the College Library (including the Gulbenkian Reading Room) and the Russian and Eurasian Studies Centre Library. The College Library keeps general collections in modern history, politics, international relations and economics, collections on Europe, Asia, and the non-Slavonic collections on Russia and the former Soviet Union. It holds over 50,000 volumes and back issues of over 300 journal titles. It also houses some 20th-century archive collections, including the Wheeler-Bennett papers. St Antony's is associated with the Oxford Libraries Information System (OLIS), and has been a contributor to the university's online union library catalogue since 1990.[citation needed]

The other libraries on the College site are the Middle East Centre Library, the Bodleian Latin American Centre Library, the Bodleian Japanese Library and the Russian and Eurasian Studies Centre Library, the last of which was refurbished in 2008–2009 as part of the college's rolling construction and rejuvenation program. The college also holds an extensive collection of archival material relating to the Middle East at the Middle East Centre Archive,[21] the premises of which were greatly expanded with the completion of Zaha Hadid's Softbridge building in mid-2014. The area studies libraries on site are unique within the university and thus generally open to all its students, regardless of college affiliation; they typically hold a wide collection of primary language sources and further Anglophone texts - an abundance of specialist material and unique expertise which prompted Leslie Woodhead to comment as follows:[6]: 221

Generations of well-informed men with unusual backgrounds have passed through the college, excavating

the remarkable library and sharing their knowledge of some of the world's more secretive places.

The college's Graduate Common Room has, since 2005, published a biannual academic journal entitled the St Antony's International Review, which is more commonly known by its acronym - STAIR. The journal represents a medium through which aspiring young academics can publish their work alongside their established policy-makers and their peers. Furthermore, the college publishes a termly newsletter, the Antonian, and a college record - an annual report on college affairs.[citation needed]

Sports and societies

[edit]

This is further fostered by the communal social life of the college. St. Antony's College Boat Club has multiple boats in Oxford's regattas, and has seen success in recent years.[22] The football club is also popular amongst students. Other societies include the gardening club.

Rankings

[edit]As a postgraduate only college, St Antony's does not appear in the university's annual Norrington Table.[citation needed]

Traditions and attributes

[edit]St Antony's is a largely informal college, mandating the wearing of academic dress (sub fusc) only for the university's matriculation and graduation ceremonies. The college does not maintain a permanent high table, instead choosing to serve high table meals on a number of occasions each week for the college's fellows and visiting academics. Students often attend high table at the invitation of their supervisors.[citation needed] As a graduate college, St Antony's students play an important role in the day-to-day business of running the college through their elected body of representatives - the Graduate Common Room or GCR.[citation needed]

Coat of arms

[edit]The college's arms were granted in 1952, and reflect the college's namesake: Anthony the Great of Egypt. The red represents the Red Sea, whilst the gold was chosen to reflect desert sands. The stars (heraldically known as "mullets") were taken from the founder's trade mark, whilst the T-shaped elements are traditional crosses of St Antony. The heraldic blazon for these arms is as follows:

Or on a chevron between three tau crosses gules as many pierced mullets of the field.

The college's motto 'plus est en vous' is sometimes added in complement to its arms: they are typically placed upon a scroll beneath the escutcheon (shield); this version of the arms is most commonly found on the cover of St Antony's Papers issues. The motto itself can be translated literally as "there is more in you", although it is commonly taken to imply the following English expression: "There is more to you than meets the eye".[citation needed]

Grace

[edit]St Antony's is one of nine colleges at the university to employ the 'two-word' Latin grace. This is statistically the most popular form of grace said at hall in Oxford and also in Cambridge, where it is used by five colleges. The grace is read out in two parts at the college's formal meals, which take place thrice each term. The first half of the grace or ante cibum is said before the start of the meal and the second, the post cibum, once the meal has ended. It is read as follows:

Benedictus benedicat - "May the Blessed One give a blessing"

Benedicto benedicatur - "Let praise be given to the Blessed One"

The grace is said in keeping with tradition. However, unlike at most Oxford colleges, St Antony's does not require its students to stand and acknowledge the saying of grace. The second half of the grace or post cibum can also be translated (based on the ablative case rather than the dative case) as "Let a blessing be given by the Blessed One".

People associated with St Antony's

[edit]Wardens

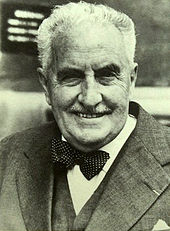

[edit]The first Warden of the college was Sir William Deakin (1950–1968), a young Oxford academic who in the Second World War became an adventurous soldier and aide to Winston Churchill. He won Antonin Besse's confidence and played the key role in turning his vision into the centre of excellence that St Antony's has become. Sir Raymond Carr (1968–1987), a distinguished historian of Spain, expanded the college and its regional coverage and opened its doors to visiting scholars from all over the world.

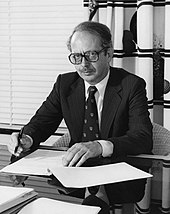

Sir Ralf Dahrendorf (later Lord Dahrendorf) (1987–1997) came to St Antony's after a distinguished career as a social theorist and politician in Germany, a European Commissioner and Director of the London School of Economics. He further enlarged the college and developed its role as a source of policy advice. The previous Warden, Sir Marrack Goulding (1997–2006), served in the British Diplomatic Service for 26 years before becoming an Under Secretary-General at the United Nations. His appointment underlined the international nature of the college and its links with government and business. Following the retirement of the fifth Warden of the College Margaret MacMillan in October 2017, social anthropologist Roger Goodman was elected Warden, having previously served in an acting capacity between 2006 and 2007.[23]

- Sir William Deakin, 1950–68

- Sir Raymond Carr, 1968–87

- Sir Ralf Dahrendorf (1987–1993), later Lord Dahrendorf, 1987–97

- Sir Marrack Goulding, 1997–2006

- Roger Goodman, (acting), October 2006–July 2007

- Margaret MacMillan, 2007–17

- Roger Goodman, 2017–

Former students

[edit]

St Antony's alumni (Antonians) have achieved success in a wide variety of careers; these include writers, politicians, academics and a large number of civil servants, diplomats and representatives of international organisations.

Former students with careers as politicians and civil servants include Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, the 6th President of Iceland, Álvaro Uribe, who was President of Colombia from 2002 to 2010 and his Minister of Foreign Affairs Jaime Bermúdez, Yigal Allon, a deputy and acting Prime Minister of Israel, former Vice President of the European Commission and current Finnish Minister of Economic Affairs Olli Rehn, the Dutch Minister of Finance and former Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation and former UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon Sigrid Kaag, the former Secretary of State for Wales John Redwood, former EU Commissioner Jean Dondelinger, the Canadian politician John Godfrey, Gary Hart, a former US Senator and presidential candidate, and US Rep. Tom Malinowski (D-NJ), a former US Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. Diplomats Joseph A. Presel, Gustavo Bell and Shlomo Ben-Ami are also Antonians. Furthermore, Minouche Shafik, Deputy Governor of the Bank of England and former managing director of the International Monetary Fund, is an Antonian, as are three-time Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Thomas Friedman and Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Dexter Filkins.

Further Antonians include Anne Applebaum, former editor at The Economist, Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, Member of the European Parliament, book author Agnia Grigas, the Bulgarian communist Lyudmila Zhivkova, Indian journalist Sagarika Ghose and Rhodes scholar Chrystia Freeland, Canada's Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, and a former director at Thomson Reuters.

In academia, Sir Christopher Bayly was Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History at the University of Cambridge, whilst Wm. Roger Louis is Kerr Chair in English History and Culture at the University of Texas at Austin, Craig Calhoun, current president of the Berggruen Institute is the former director of the London School of Economics, where he remains Centennial Professor, Frances Lannon is the principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Richard Evans is the Regis professor of Modern History at Cambridge, Anthony Venables holds Oxford's BP professorship in Economics and was Chief Economist at the UK's Department for International Development; Paul Kennedy is the Dilworth professor of British History at Yale, Rashid Khalidi a professor at Columbia and Michael T. Benson is the president of Coastal Carolina University.

The college also counts the Olympic gold medal-winning swimmer Davis Tarwater, violinist and conductor Joji Hattori, screenwriter Julian Mitchell and the historian Margaret MacMillan amongst its alumni.

Academics

[edit]- Timothy Garton Ash, journalist and author on European matters

- Mats Berdal, Professor of Security and Development at the Department of War Studies, King's College London.

- Archie Brown, historian of the end of the Cold War and author of The Gorbachev Factor

- Paul Collier, Director of the Centre for the Study of African Economies at Oxford

- Michael Kaser, economist and author of Soviet Economics

- Homa Katouzian, literary critic and scholar of Iranian studies

- Paul Kennedy, J. Richardson Dilworth Professor of History; Director, International Security Studies, Yale University

- Alan Knight, post-critical historian, Director of the Latin American Centre, and author of the two-volume award-winning book The Mexican Revolution (1986)

- Wm. Roger Louis, historian and scholar of the British Empire, especially Decolonization.

- Kalypso Nicolaïdis, Professor of International Relations and Director of the European Studies Centre

- Tariq Ramadan, Professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies

- Oliver Ready, translator of Russian literature

- Eugene Rogan, historian of the Modern Middle East and author of The Arabs: A History

- Robert Service, historian of the USSR and biographer of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin

- Avi Shlaim, historian writing on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

- Vivienne Shue, FBA, sinologist and author of "The Reach of the State"

- Omer Bartov, historian writing on genocide focused on the Holocaust; author of seven books.

- Arnab Goswami, Journalist, Editor-in-Chief(Republic Media Networks)

Former fellows

[edit]- Michael Herman, founder of the Oxford Intelligence Group[24]

- Foulath Hadid, Honorary Fellow

- Albert Hourani, Founder-Director, Middle East Centre, St Antony's College, Oxford

- James Joll, historian, fellow (1950–67)

- Sudipta Kaviraj, Professor of Political Sciences, Columbia University, New York

- Frank McLynn, historian and biographer

- Tapan Raychaudhuri, Emeritus Fellow, St Antony's College, Oxford

- Giulio Angioni, Italian writer and anthropologist

- José Cutileiro, Portuguese diplomat, historian, and author

- Michael Aris, leading Western authority on Bhutanese, Tibetan and Himalayan culture, Husband of Burmese opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "St Antony's College". University of Oxford. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Statutes of St Antony's College, Oxford". 13 February 2015.

- ^ a b Nicholls, C. (2000). The History of St Antony's College, Oxford, 1950–2000. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–31. ISBN 978-0-230-59883-6.

- ^ "St Antony's College : Annual Report and Financial Statements : Year ended 31 July 2021" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. p. 23. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ a b "History of St Antony's College". www.sant.ox.ac.uk. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b Woodhead, Leslie (2005). My Life as a Spy. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4086-0.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (18 May 2014). "Back in the USSR: my life as a 'spy' in the archives". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Harrison, Brian, ed. (1994). The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 625. ISBN 978-0-19-822974-2.

- ^ Saint, Andrew (1973). "Charles Buckeridge and his family" (PDF). Oxoniensia. 38: 357–372.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Gateway Campaign". St Antony's College, Oxford. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Obituary - 'Foulath Hadid: Writer and expert on Arab affairs' - The Independent 11 October 2012

- ^ "Work starts on futuristic Oxford University building". The Oxford Times. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (14 June 2015). "Zaha Hadid's Middle East Centre lands in Oxford". The Sunday Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Jay Merrick (26 May 2015). "Zaha Hadid's modernist library inspires shock and awe in Oxford". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ a b Wainwright, Oliver (23 June 2016). "RIBA awards 2016: academic buildings dominate list of UK's best architecture". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "St Antony's GCR". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- ^ Davidjgill (13 December 2011). "The Modern Buildings of St Athony's College". slideshare.net.

- ^ "Home". Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ ""St. Antony's College Oxford - a history of its buildings and site"". Archived from the original on 6 September 2011.

- ^ "MEC Archive | St Antony's College". www.sant.ox.ac.uk. 8 December 2014.

- ^ "St Antony's GCR". Archived from the original on 6 December 2011.

- ^ "Sixth Warden of St Antony's College | St Antony's College". www.sant.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Phythian, Mark (2017). "Profiles in intelligence: an interview with Michael Herman". Intelligence and National Security. 32 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/02684527.2016.1199529. hdl:2381/39688. S2CID 156393867. – via Taylor & Francis (subscription required)