Bard College

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

| |

Former name | St. Stephen's College (1860–1934) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Dabo tibi coronam vitae (Latin) |

Motto in English | I shall give thee the crown of life (Revelation 2:10) |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | March 1860 |

Religious affiliation | Episcopal Church |

Academic affiliation | Annapolis Group |

| Endowment | $412.4 million[1] |

| President | Leon Botstein |

| Provost | Deirdre d’Albertis |

Academic staff | 274 |

| Students | 2,272 |

| Undergraduates | 1,852 |

| Postgraduates | 420 |

| Location | , , United States 42°01′13″N 73°54′36″W / 42.02028°N 73.91000°W |

| Campus | Rural, 1,260 acres (510 ha) |

| Colors | Red and white[2] |

| Nickname | Raptors[3] |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III Liberty League |

| Website | www |

| |

Bard College is a private liberal arts college in the hamlet of Annandale-on-Hudson, in the town of Red Hook, in New York State. The campus overlooks the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains within the Hudson River Historic District—a National Historic Landmark.

Founded in 1860, the institution consists of a liberal arts college and a conservatory, as well as eight graduate programs offering over 20 graduate degrees in the arts and sciences.[4] The college has a network of over 35 affiliated programs, institutes, and centers, spanning twelve cities, five states, seven countries, and four continents.[5]

History

[edit]Origins and early years

[edit]

During much of the nineteenth century, the land since owned by Bard was mainly composed of several country estates. These estates were called Blithewood, Bartlett, Sands, Cruger's Island, and Ward Manor/Almont.[citation needed]

In 1853, John Bard and Margaret Bard purchased a part of the Blithewood estate and renamed it Annandale. John Bard was the grandson of Samuel Bard, a prominent doctor, a founder of Columbia University's medical school, and physician to George Washington.[6] John Bard was also the nephew of John McVickar, a professor at Columbia University. The family had strong connections with the Episcopal Church and Columbia.[citation needed]

The following year, in 1854, John and Margaret established a parish school on their estate in order to educate the area's children. A wood-frame cottage, known today as Bard Hall, served as a school on weekdays and a chapel on weekends. In 1857, the Bards expanded the parish by building the Chapel of the Holy Innocents next to Bard Hall.[7] During this time, John Bard remained in close contact with the New York leaders of the Episcopal Church. The church suggested that he found a theological college.[8]

With the promise of outside financial support, John Bard donated the unfinished chapel, and the surrounding 18 acres (7.3 ha), to the diocese in November 1858. In March 1860, St. Stephen's College was founded. In 1861, construction began on the first St. Stephen's College building, a stone collegiate Gothic dormitory called Aspinwall, after early trustee John Lloyd Aspinwall, brother of William Henry Aspinwall. During its initial years, the college relied on wealthy benefactors, like trustee Cornelius Vanderbilt, for funding.[9]

The college began taking shape within four decades. In 1866, Ludlow Hall, an administrative building, was erected. Preston Hall was built in 1873 and used as a refectory. A set of four dormitories, collectively known as Stone Row, were completed in 1891. And in 1895, the Greek Revival Hoffman Memorial Library was built.[10] The school officially changed its name to Bard College in 1934 in honor of its founder.[citation needed]

Growth and secularization

[edit]

In the 20th century, social and cultural changes amongst New York's high society would bring about the demise of the great estates. In 1914, Louis Hamersley purchased the fire-damaged Ward Manor/Almont estate and erected a Tudor style mansion and gatehouse, or what is today known as Ward Manor.[11] Hamersley expanded his estate in 1926 by acquiring the abandoned Cruger's Island estate. That same year, after Hamersley's combined estate was purchased by William Ward, it was donated to charity and served as a retirement home for almost four decades.[citation needed]

By the mid-1900s, Bard's campus significantly expanded. The Blithewood estate was donated to the college in 1951, and in 1963, Bard purchased 90 acres (36 ha) of the Ward Manor estate, including the main manor house. The rest of the Ward Manor estate became the 900-acre (360 ha) Tivoli Bays nature preserve.[12][13]

In 1919, Bernard Iddings Bell became Bard's youngest president at the age of 34. His adherence to classical education, decorum, and dress eventually clashed with the school's push towards Deweyism and secularization, and he resigned in 1933.[14]

In 1928, Bard merged with Columbia University, serving as an undergraduate school similar to Barnard College. Under the agreement, Bard remained affiliated with the Episcopal Church and retained control of its finances. The merger raised Bard's prestige; however, it failed to provide financial support to the college during the Great Depression.[15] So dire was Bard's financial situation that in 1932, then-Governor of New York and College trustee Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a telegram to the likes of John D. Rockefeller Jr., George Eastman and Frederick William Vanderbilt requesting donations for the college.[16]

On May 26, 1933, Donald Tewksbury, a Columbia professor, was appointed dean of the college. Although dean for only four years, Tewksbury had a lasting impact on the school. Tewksbury, an educational philosopher, had extensive ideas regarding higher education. While he was dean, Tewksbury steered the college into a more secular direction and changed its name from St. Stephen's to Bard. He also placed a heavy academic emphasis on the arts, something atypical of colleges at the time, and set the foundations for Bard's Moderation and Senior Project requirement.[15][17] While Tewksbury never characterized Bard's curriculum as "progressive," the school would later be considered an early adopter of progressive education. In his 1943 study of early progressive colleges, titled General Education in the Progressive College, Louis T. Benezet used Bard as one of his three case studies.[15][18]

During the 1940s, Bard provided a haven for intellectual refugees fleeing Europe. These included Hannah Arendt, the political theorist, Stefan Hirsch, the precisionist painter; Felix Hirsch, the political editor of the Berliner Tageblatt; the violinist Emil Hauser; the linguist Hans Marchand; the noted psychologist Werner Wolff; and the philosopher Heinrich Blücher.[15] Arendt is buried at Bard, alongside her husband Heinrich Blücher, as is eminent novelist Philip Roth.[19]

In 1944, as a result of World War II, enrollment significantly dropped putting financial stress on the college. In order to increase enrollment, the college became co-educational, thereby severing all ties with Columbia. The college became an independent, secular, institution in 1944. Thus enrollment more than doubled, from 137 students in 1944, to 293 in 1947.[20] In the 1950s, with the addition of the Blithewood estate and Tewksbury Hall, the college would increase its enrollment by 150 students.[citation needed]

Late twentieth and early twenty-first century

[edit]Donald Fagen and Walter Becker's experiences at Bard prompted them to write the 1973 song "My Old School" for their rock group, Steely Dan.[21] The song was motivated by the 1969 drug bust at Bard in which the college administration colluded.[22] The DA involved was G. Gordon Liddy of Watergate notoriety.[23] Fagen wrote another Steely Dan song, "Rikki Don't Lose That Number", about novelist, artist and former Bard faculty spouse Rikki Ducornet.[24]

In 2020, Bard College and Central European University became the founding members of the Open Society University Network, a collaborative global education initiative endowed with US$1 billion. As part of this new initiative, the college received a US$100 million gift from the Open Society Foundations which ranks among the largest financial contributions to a U.S. institution in recent history.[25][26] In 2021, philanthropist George Soros made a $500 million endowment pledge to Bard College. It is one of the largest pledges of money ever made to higher education in the United States.[27]

In June 2021, Bard College was declared an "undesirable institution" in Russia, becoming the first international higher education organization to be branded with this designation.[28] Bard president Botstein hypothesized that this tag was due their association with and funding from the Open Society Foundations which was also classified as undesirable in Russia and related conspiracy theories about George Soros.[29]

College leaders

[edit]At various times, the leaders of the college have been titled president, warden or dean.[30] They are listed below:

- George Franklin Seymour (1860–1861)

- Thomas Richey (1861–1863)

- Robert Brinckerhoff Fairbairn (1863–1898)

- Lawrence T. Cole (1899–1903)

- Thomas R. Harris (1904–1907)

- William Cunningham Rodgers (1909–1919)

- Bernard Iddings Bell (1919–1933)

- Donald George Tewksbury (1933–1937)

- Harold Mestre (1938–1939)

- Charles Harold Gray (1940–1946)

- Edward C. Fuller (1946–1950)

- James Herbert Case Jr. (1950–1960)

- Reamer Kline (1960–1974)

- Leon Botstein (1975–Present)

Campus

[edit]The campus of Bard College is in Annandale-on-Hudson, a hamlet in Dutchess County, New York, United States, in the town of Red Hook. It contains more than 70 buildings with a total gross building space of 1,167,090 sq ft (108,426 m2) and was listed as a census-designated place in 2020.[31][32] Campus buildings represent varied architectural styles, but the campus remains heavily influenced by the Collegiate Gothic and Postmodern styles.

Bard's historic buildings are associated with the early development of the college and the history of the Hudson River estates (see Bard College History).[11] During a late twentieth-century building boom, the college embraced a trend of building signature buildings designed by prominent architects like Venturi, Gehry, and Viñoly.[33]

In January 2016, Bard purchased Montgomery Place, a 380-acre (150 ha) estate adjacent to the Bard campus, with significant historic and cultural assets. The estate consists of a historic mansion, a farm, and some 20 smaller buildings. The college purchased the property from Historic Hudson Valley, the historical preservation organization that had owned Montgomery Place since the late 1980s. The addition of this property brings Bard's total campus size to nearly 1,000 acres (400 ha) along the Hudson River in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.[34]

In late 2023, Bard purchased 260 acres of land adjacent to the Montgomery Place campus in Barrytown, which used to be the campus of the Unification Theological Seminary. The property, originally owned by the Livingston and later Aspinwall families, features a mansion designed by William Appleton Potter. It was acquired by the De La Salle Brothers in 1928, who completed a large seminary and normal institute there in 1931. In turn, the property was sold in 1974 to the Unification Church.[35] Bard intends to use the space to provide new studios for the Center for Human Rights and the Arts and administrative offices for the Open Society University Network (OSUN), of which Bard is a founding member. The purchase of the property brings Bard's total acreage to 1260 acres (510 ha).[36]

The area around the campus first appeared as a census-designated place (CDP) in the 2020 Census,[37] with a population of 358.[38]

The college has an amount of housing for faculty members.[39] School-age dependents in this faculty housing are in the Red Hook Central School District (the CDP is within this school district).[40]

-

Stone Row, a dormitory built in 1891

-

The Chapel of the Holy Innocents, built in 1857, serves several denominations on campus.

-

Reem-Kayden Center for Science and Computation

-

Tewksbury Hall, a dormitory

-

The Ravines, dormitories

-

Alumni Houses, dormitories

-

Stewart and Lynda Resnick Commons, a residential village with dormitories

-

Cruger Hall, a dormitory

-

Hessel Museum, museum of contemporary art

-

Blithewood Manor, a historic estate housing the Levy Economics Institute dating to 1899

-

Blithewood Garden, Italianate walled garden

-

Ward Manor, built in 1918 and now used as a dormitory

-

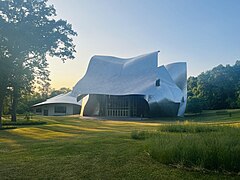

Fisher Center at Bard, performance hall designed by Frank Gehry

-

Montgomery Place, a historic mansion purchased by the college in 2016

-

The former chapel and side wings of the Normal Institute building at Bard's Massena Campus

-

Massena House at Bard's Massena Campus

Academics

[edit]Rankings and awards

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[41] | 60 |

| Washington Monthly[42] | 95 |

| National | |

| Forbes[43] | 230 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[44] | 264 |

In its 2022-2023 edition of college rankings, U.S. News & World Report ranked Bard 60th overall, 5th in "Most Innovative Schools", tied at 38th for "Best Undergraduate Teaching", tied at #70 in "Top Performers on Social Mobility", tied at #19 in "First-Year Experiences", and 19th for "Best Value" out of 210 "National Liberal Arts Colleges" in the United States.[45]

Bard's Master of Fine Arts program was ranked one of ten most influential Master of Fine Arts programs in the world by Artspace Magazine in 2023.[46]

Bard has been named a top producer of U.S. Fulbright Scholars.[47] Many Bard alumni have also been named Watson Fellows, Critical Language Scholarship recipients, Davis Projects for Peace winners, Rhodes Scholars, Marshall Scholars, and Peace Corps fellows, among other postgraduate awards.[48][49][50][51]

Undergraduate programs

[edit]In the undergraduate college, Bard offers Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees. There are 23 academic departments that offer over 40 major programs, as well as 12 interdisciplinary concentrations. The college was the first in the nation to offer a human rights major.[52] Its most popular undergraduate majors, based on 2021 graduates, were:[53]

- Social Sciences (140)

- Fine/Studio Arts (106)

- English Language and Literature/Letters (81)

- Biological and Physical Sciences (80)

In the three weeks preceding their first semester, first-year students attend the Language and Thinking (L&T) program, an intensive, writing-centered introduction to the liberal arts. The interdisciplinary program, established in 1981, aims to "cultivate habits of thoughtful reading and discussion, clear articulation, accurate self-critique, and productive collaboration."[54] The program covers philosophy, history, science, poetry, fiction, and religion. In 2011, the core readings included works by Hannah Arendt, Franz Kafka, Frans de Waal, Stephen Jay Gould, Clifford Geertz, M. NourbeSe Philip, and Sophocles.[55]

The capstone of the Bard undergraduate experience is the Senior Project, commonly referred to as SPROJ amongst its students.[56][failed verification] As with moderation, this project takes different forms in different departments. Many students write a paper of around eighty pages, which is then, as with work for moderation, critiqued by a board of three professors. Arts students must organize a series of concerts, recitals, or shows, or produce substantial creative work; math and science students, as well as some social science students, undertake research projects.[citation needed]

Undergraduate admissions

[edit]For the academic year 2022-2023, Bard's acceptance rate stands at 46%. Out of the total 6,482 students who applied, 2,982 were admitted to the school.[57] For the 2022–2023 academic year 447 students enrolled representing a yield rate of 15%. Admission trends note a 25% increase in applications in the 2022–2023 academic year.[58] Bard does not require applicants to submit SAT or ACT test scores in order to apply.[59] As an alternative, applicants may take an examination composed of 19 essay questions in four categories: Social Studies; Languages and Literature; Arts; and Science, Mathematics, and Computing, with applicants required to complete three 2,500-word essays covering three of the four categories.[60] For admitted students who submitted test scores, 50% had an SAT score between 1296 and 1468 or an ACT score between 28 and 33, with a reported average GPA of 3.79. Admissions officials consider a student's GPA a very important academic factor. Honors, AP, and IB classes are important, an applicant's high school class rank is considered, and letters of recommendation are considered very important for admissions officials at Bard.[61][62]

Graduate programs

[edit]Bard College offers a range of postgraduate degree programs, including the Bard MFA, Bard Graduate Center, Center for Curatorial Studies, Center for Human Rights and the Arts, Center for Environmental Policy, Bard MBA in Sustainability, Levy Economics Institute, the Master of Arts in Teaching, and the Master of Arts in Global Studies.

Bard MFA

[edit]Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts is a nontraditional graduate school for interdisciplinary study in the visual and creative arts. The program takes place over two years and two months, with students residing on campus during three consecutive summers, and two winter sessions of independent study completed off campus.[63] Notable artists and writers that have been affiliated with the Bard MFA as faculty and visiting artists include Marina Abramovic, Eileen Myles, Paul Chan, Robert Kelly, Tony Conrad, Okkyung Lee, Yto Barrada, Carolee Schneemann, Lynne Tillman, and Ben Lerner.[64]

Bard Graduate Center

[edit]The Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture is a graduate research institute and gallery located in New York City. Established in 1993, the institute offers a two-year MA program and a PhD program that began in 1998. The institute's facilities include a gallery space at 18 West 86th Street and an academic building with a library at 38 West 86th Street.[65]

Center for Curatorial Studies

[edit]

The Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College (CCS Bard) established in 1990, is a museum and research center dedicated to the study of contemporary art and exhibition practices from the 1960s to the present. In 1994, CCS Bard launched its (MA) Master of Arts in Curatorial Studies program.[66] The center also hosts public events throughout the year including lectures and panel discussions on topics in contemporary art.[citation needed]

The museum, spanning an area of 55,000 square feet, offers a variety of exhibitions accessible to the general public throughout the year. It houses two distinct collections, the CCS Bard Collection and the Marieluise Hessel collection, which has been loaned to CCS Bard on a permanent basis. Artists such as Keith Haring, Julian Schnabel, Wolfgang Tillmans, Stephen Shore, and Cindy Sherman, among numerous others, are featured within these collections.[67]

The CCS Bard Library is a research collection for contemporary art with a focus on post-1960s contemporary art, curatorial practice, exhibition histories, theory, and criticism. in 2023 historian Robert Storr donated over 25,000 volumes to the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, nearly doubling the total collection size to 63,000 volumes.[68] Other noteworthy contributors include Louise Bourgeois, Yto Barrada, Leon Golub, Jenny Holzer, Gerhard Richter, and Rachel Whiteread.[citation needed]

In 2022 CCS Bard received $50 million from a $25 million donation from the Gochman Family Foundation to form a Center for American and Indigenous Studies at CCS Bard and a matching donation of $25 million from George Soros.[69] This followed two 2021 gifts of $25 million, one from Marieluise Hessel and a matching donation from Soros.[70]

Center for Human Rights & the Arts

[edit]

The Center for Human Rights & the Arts at Bard College is an interdisciplinary research institution dedicated to exploring the intersection of art and human rights. The center is affiliated with the Open Society University Network (OSUN). The center's flagship initiative is the Master of Arts program in Human Rights & the Arts.[71] The center includes initiatives such as resident research fellowships, research grants, artist commissions, public talks, accessible publications, and a biennial arts festival organized in partnership with the Fisher Center at Bard and other OSUN institutions and art venues worldwide.[citation needed]

Center for Environmental Policy

[edit]The Center for Environmental Policy (CEP) at Bard College is a research institution offering a range of graduate degree programs focused on environmental policy, climate science, and environmental education. The CEP offers a series of graduate degrees including the Master of Science in Environmental Policy and Master of Education. In addition to these individual degree programs, CEP offers dual-degree options that allow students to combine their environmental studies with programs in law or business.[72]

Levy Economics Institute

[edit]

Levy Economics Institute is a public policy think tank focused on generating public policy responses to economic problems. Through research, analysis, and informed debate, the institute aims to enable scholars and leaders from business, labor, and government to collaborate on common interest issues.[73] The institute's findings are disseminated globally through various channels, including publications, conferences, seminars, congressional testimony, and partnerships with other nonprofits. Its research encompasses a wide range of topics, including stock-flow consistent macro modeling, fiscal policy, monetary policy and financial structure, financial instability, income and wealth distribution, financial regulation and governance, gender equality and time poverty, and immigration/ethnicity and social structure.[73] The Levy Economics Institute is particularly known for its research in heterodox economics, with a focus on Post-Keynesian and Marxian economics. It is additionally recognized as the leading research center for the study of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Notable individuals that have been affiliated with the Levy Economics Institute as professors, directors, and economists include Joseph Stiglitz, Hyman Minsky, William Julius Wilson, L. Randall Wray, Jan Kregel, Bruce C. Greenwald, Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, Lakshman Achuthan, Warren Mosler, Stephanie Kelton, Bill Mitchell, and Pavlina R. Tcherneva.[74]

Endowment

[edit]Bard has access to multiple, distinct endowments. Bard, along with Central European University, is a founding member of the Open Society University Network, endowed with $1 billion from philanthropist George Soros, which is a network of universities to operate throughout the world to better prepare students for current and future global challenges through integrated teaching and research.[75][76] Bard maintains its own endowment of approximately $412 million. In July 2020, Bard received a gift of $100 million from the Open Society Foundations, which will dispense $10 million yearly over a period of ten years.[77] In April 2021, Bard received a $500 million endowment challenge grant from George Soros. Once matched, on a five-year timeline, Bard will have an endowment of more than $1 billion.[78]

Programs, centers, and associated institutes

[edit]Bard has developed several graduate programs and research institutes, including the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts, the Levy Economics Institute which began offering a Masters of Science in Economic Theory and Policy in 2014, the Center for Curatorial Studies and Art in Contemporary Culture, the Bard Center for Environmental Policy, the Bard College Conservatory of Music, the ICP-Bard Program in Advanced Photographic Studies in Manhattan,[79] the Master of Arts in Teaching Program (MAT), the Bard College Clemente Program, and the Bard Graduate Center in Manhattan.

In 1990, Bard College acquired, on permanent loan, art collector Marieluise Hessel's substantial collection of important contemporary artwork. In 2006, Hessel contributed another $8 million (USD) for the construction of a 17,000-square-foot addition to Bard's Center for Curatorial Studies building, in which the collection is exhibited.[80]

The Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) provides a liberal arts degree to incarcerated individuals (prison education) in five prisons in New York State, and enrolls nearly 200 students.[81] Since federal funding for prison education programs was eliminated in 1994,[82] BPI is one of only a small number of programs of its kind in the country.[81]

Bard awards the Bard Fiction Prize annually to "a promising emerging writer who is an American citizen aged 39 years or younger at the time of application". The prize is $30,000 and an appointment as writer-in-residence at the college.[83]

The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities is located at Bard College. The center hosts an annual public conference, offers courses, runs various related academic programs, and houses research fellows.[84]

In February 2009, Bard announced the first dual degree program between a Palestinian university and an American institution of higher education. The college entered into a collaboration with Al-Quds University involving an honors college, a master's program in teaching and a model high school.[85]

In accordance with AlQuds-Bard requirements, students are not allowed to decide their major during the first year of their studies; instead, as a liberal arts college, students are advised to diverge in different classes that would allow them to decide what program they would like to take interest in as in the following year. Students are encouraged to look upon different classes to help them decide the subject they would mostly enjoy studying. Bard gives students the opportunity to dissect different programs before committing to a specific major. As a policy, throughout a student's undergraduate years, they must distribute their credits among different courses so that they can liberally experience the different courses Bard has to offer.[86]

In June 2011, Bard officially acquired the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Massachusetts,[87] and in November 2011, Bard took ownership of the European College of Liberal Arts in Berlin, Germany, to become Bard College Berlin.[88]

In 2013, Bard entered into a comprehensive agreement with Soochow University in Suzhou, China, that will include a joint program between the Soochow University School of Music and the Bard College Conservatory of Music, exploration leading to the establishment of The Bard College Liberal Arts Academy at Soochow University, and student exchange.[89]

In 2020, Bard announced that through the new Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Advanced Achievement Scholars program the college will offer admission to high school juniors within 120 miles from the college based on an essay process based on the popular Bard Entrance Exam, first launched in 2013.[90]

Student life

[edit]Over 120 student clubs are financed through Bard's Convocation Fund, which is distributed once a semester by an elected student body and ratified during a public forum.[citation needed] Bard College has one print newspaper, the Bard Free Press, which was awarded a Best in Show title by the Associated Collegiate Press in 2013.[91] In 2003, the Bard Free Press won Best Campus Publication in SPIN Magazine's first annual Campus Awards.[92] Student-run literary magazines include the semiannual Lux, The Moderator, and Sui Generis, a journal of translations and of original poetry in languages other than English. The Draft, a human rights journal, the Bard Journal of the Social Sciences, Bard Science Journal, and Qualia, a philosophy journal, are also student-published. Bard Papers is a privately funded literary magazine operated jointly between faculty and students.[citation needed]

Other prominent[according to whom?] student groups include: the International Students Organization (ISO), Afropulse, Latin American Student Organization (LASO), Caribbean Student Association (CSA), Asian Student Organization (ASO), Bard Musical Theatre Company (BMTC), Black Student Organization (BSO), Anti-Capitalism Feminist Coalition, Body Image Discussion Group, Self-Injury Support and Discussion, Bard Film Committee, Queer Student Association, Trans Life Collective, The Scale Project, Student Labor Dialogue, Bard Debate Union, Bard Model UN, Surrealist Training Circus, Bard Bike Co-Op, Bard Bars, Bard POC Theater Ensemble, and college radio station WXBC.[93] WXBC was founded in 1947.[94] In 2006, WXBC was nominated for "Station of the Year" and "Biggest Improvement" in the CMJ College Radio Awards.[95]

Bard has a strong independent music scene considering its isolation and size.[according to whom?] The college's Old Gym was once a popular location for concerts and parties in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. In 2004, the Old Gym was shut down and in spring 2006 transformed into a student-run theater by students Brel Froebe, Julie Rossman, and Kell Condon.[citation needed] Many activities that once took place there, occur in the smaller SMOG building. SMOG is primarily used as a music venue featuring student-run bands.[96][failed verification]

Athletics

[edit]Bard College teams participate as a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Division III. The Raptors are a member of the Liberty League. Prior conference affiliations include the Skyline Conference and the former Hudson Valley Athletic Conference. Women's sports include basketball, cross country, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field, volleyball and squash. Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, soccer, squash, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field and volleyball.[citation needed]

One of the more popular club sports on campus is rugby.[according to whom?] Bard College Rugby Football Club fields men's and women's teams that compete in the Tristate Conference, affiliated with National Collegiate Rugby. Additional club sports include: ultimate frisbee, fencing, and equestrian.[97]

Alumni and faculty

[edit]Notable alumni

[edit]Notable alumni of Bard include fraternal songwriters Richard M. Sherman[98] and Robert B. Sherman,[citation needed] comedian and actor Chevy Chase (1968);[99] Walter Becker and Donald Fagen of Steely Dan (1969);[21] actors Blythe Danner (1965),[citation needed] Adrian Grenier,[citation needed] Gaby Hoffmann,[citation needed], Mia Farrow (did not graduate) Jonah Hill (did not graduate), Ezra Miller (did not graduate), Griffin Gluck (Did Not Graduate) and Larry Hagman (did not graduate);[100] filmmakers Gia Coppola,[101] Todd Haynes (MFA),[102] Sadie Bennings (MFA),[103] and Lana Wachowski (did not graduate);[104] photographer Herb Ritts;[105] actor and director Christopher Guest;[106] songwriter Billy Steinberg;[107] theater director Anne Bogart;[citation needed] screenwriter Howard E. Koch;[citation needed] writer David Cote;[108] comedians Adam Conover[109]and Raphael Bob-Waksberg;[110] fashion designer Tom Ford (did not graduate),[111] classical composer Bruce Wolosoff;[citation needed] journalist Ronan Farrow;[112] writer and social theorist Albert Jay Nock;[113] Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys (did not graduate);[114] and artists Tschabalala Self,[115] and Frances Bean Cobain (did not graduate)[116].

-

Jonah Hill, Actor (did not graduate)

-

Tom Ford, Designer (did not graduate)

-

Steely Dan, Rock Band (1969)

-

Chevy Chase, Actor (1968)

-

Ezra Miller, actor (did not graduate)

-

Raphael Bob-Waksberg, writer and producer (2006)

-

Lana Wachowski, director and producer (did not graduate)

-

Gia Coppola, director (2009)

-

Mia Farrow, actress (did not graduate)

-

Adam Yauch, rapper (did not graduate)

Notable faculty

[edit]Among the college's most well-known former faculty are Toni Morrison,[117] Heinrich Blücher,[118] Hannah Arendt, Roy Lichtenstein,[citation needed] Mary McCarthy,.[119] Arthur Penn,[citation needed], Nathan Thrall,[120] Vik Muniz, Mitch Epstein, Larry Fink, John Ashbery,[citation needed] Richard Teitelbaum,[121] Mary Lee Settle (part time),[122] Andre Aciman,[123] Orhan Pamuk,[124] Chinua Achebe,[125] Charles Burnett,[126] Bill T. Jones,[127] and Alexander Soros.[128] Notable current faculty, as of 2024,[update] include Stephen Shore,[129] An-My Lê,[130] Neil Gaiman,[131] Jeffrey Gibson[132] Gilles Peress,[133] John Ryle,[134] Tan Dun,[135] Walid Raad,[136] Daniel Mendelsohn[137],Thomas Chatterton Williams, Hua Hsu,[138] Kobena Mercer,[139] Joseph O’Neill,[140] Ian Buruma,[141] Judy Pfaff,[142] Joan Tower,[143][144] Walter Russell Mead,[145] Nayland Blake,[146] Nuruddin Farah,[147] Mona Simpson[148],Sky Hopinka (MFA Faculty),[149] Masha Gessen (visiting writer),[150] Kelly Reichardt (artist in residence),[151] Francine Prose (writer in residence),[152][153] Susan Weber,[154] Lauren Cornell,[155] Ann Lauterbach,[156] Valeria Luiselli,[157] and Tschabalala Self (visiting artist in residence).[158]

-

Toni Morrison, novelist

-

Hannah Arendt, philosopher

-

Roy Lichtenstein, artist

-

Vik Muniz, artist

-

John Ashbery, poet

-

Stephen Shore, photographer

-

Neil Gaiman, writer

-

Nuruddin Farah, novelist

-

Jeffrey Gibson, artist

-

Masha Gessen, Journalist

References

[edit]- ^ "About". Bard.edu. May 9, 2013.

- ^ "Student Services". Bard.edu. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ "Bard Athletics and Recreation". Bard.edu. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Endowment". Bard College. May 9, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ "Institutes". Bard College. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ Hirsch, Felix (October 1941). "The Bard Family". Columbia University Quarterly. Bard College Archives, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.

- ^ Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. p. 15. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Hopson, George (1910). Reminiscences of St. Stephen's College. New York, NY: Edwin S. Gorham. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Magee, Christopher (1950). The History of St. Stephen's College 1860-1933. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College Senior Project. p. 38.

- ^ John Milner Associates Inc. (December 2008). Bard College Master Preservation Plan (Report). p. 27.

- ^ a b Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960. Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Bard College Archives". Bard College. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ John Milner Associates Inc. (December 2008). Bard College Master Preservation Plan (Report). p. 34.

- ^ Kirk, Russell (1963). Confessions of a Bohemian Tory. Fleet Publishing Corporation. p. 162.

- ^ a b c d "About Bard | History of Bard". Bard.edu. May 21, 2011. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960 (PDF). Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960 (PDF). Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. p. 104. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960 (PDF). Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. p. 106. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Hannah Arendt Center News". hac.bard.edu. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Kline, Reamer (1982). Education for the Common Good: A History of Bard College The First 100 Years, 1860-1960 (PDF). Annandale-on-Hudson, NY: Bard College. p. 120. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Brunner, Rob (March 17, 2006). "The origins of Steely Dan". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Back to Annandale". March 17, 2006. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "G. Gordon Liddy (Yes, the Watergate guy), Bard College, & Steely Dan". Poughkeepsie Journal. April 6, 1968. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ McCormack, J.W. (May 20, 2016). "The Burden of Strangeness: Rikki Ducornet". PWxyz, LLC. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Open Society Foundations Gives Bard $100 Million | Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com. July 2, 2020. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Major Private Gifts to Higher Education - the Chronicle of Higher Education". Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College Receives $500 Million Endowment Pledge from Investor and Philanthropist George Soros". www.bard.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Redden, Elizabeth (July 9, 2021). "Bard College Declared 'Undesirable' in Russia". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Fischer, Karin (June 22, 2021). "Bard President Is 'Heartbroken' About Russian Blacklisting". Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ College, Bard. "Bard College History at Bard College". www.bard.edu. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ "GHG Report for Bard College". American College & University Presidents' Climate Commitment. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ "State of New York Census Designated Places - Current/BAS20 - Data as of January 1, 2019". U.S. Census Bureau. January 1, 2019. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ "Facilities". Bard College. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ^ Kemble, William J. (January 13, 2016). "Bard College completes $18M purchase of Montgomery Place". dailyfreeman.com. Daily Freeman. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ "A Short History of Unification Theological Seminary: The Barrytown Years, 1975-2019". www.journals.uts.edu. Retrieved September 8, 2024.

- ^ Larson, Jamie (September 14, 2023). "Bard College Announces $14 Million Purchase of Former Unification Church Compound After Months of Rumors". The Hudson Valley Pilot. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Bard College CDP, NY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "Bard College CDP, New York". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "The Faculty Handbook 2019-2020" (PDF). Bard College. July 2019. p. 79 (PDF p. 83/150). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Dutchess County, NY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 1 (PDF p. 2/7). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

Bard College[...]UNI 24240*

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "Bard College Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2023. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "10 of the Most Influential MFA Programs in the World". Artspace. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College Named a Top Producer of Fulbright U.S. Students and U.S. Scholars for 2019–20". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Two Bard College Seniors Win Prestigious Watson Travel Fellowships | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Two Bard College Students Win Critical Language Scholarships for Foreign Language Study Abroad | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College Student Wins Davis Projects For Peace Prize". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College Alumnus Ronan S. Farrow '04 Awarded Prestigious Rhodes Scholarship | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ "Bard College Catalogue". Bard College. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Bard College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Archived from the original on April 13, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Language and Thinking". Bard College. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ "Language and Thinking Anthology". Bard College. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ College, Bard. "Undergraduate Curriculum at Bard College". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Bard College Acceptance Rate and SAT/ACT Scores". www.collegetuitioncompare.com. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "How Bard College's Acceptance Rate Changes". College Tuition Compare. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Undergraduate Admission". bard.edu. Bard College. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "The Bard Entrance Examination". bard.edu. Bard College. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Bard College Admissions". usnews.com. U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Bard College SAT Scores and GPA". prepscholar.com. PrepScholar. Archived from the original on January 5, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Program". www.bard.edu. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ "People". www.bard.edu. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bard Graduate Center". www.bgc.bard.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (September 23, 2022). "After a $50 M. Gift to Celebrate 30 Years, Bard's Center for Curatorial Studies Looks Toward the Future". ARTnews.com. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Collections – eMuseum". bard.emuseum.com. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Robert Storr Donates Archive to CCS Bard". www.artforum.com. March 29, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Nietzel, Michael T. "Bard College Receives $50 Million For Indigenous Studies". Forbes. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Block, Fang. "Marieluise Hessel Foundation and George Soros Each Donate $25 Million to Bard College". www.barrons.com. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Home". Center for Human Rights and the Arts. May 31, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Bard Graduate Programs in Sustainability". gps.bard.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "Levy Economics Institute of Bard College". www.levyinstitute.org. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Levy Economics Institute | About Us". www.levyinstitute.org. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Communications (January 23, 2020). "George Soros Launches Global Network to Transform Higher Education". Open Society Foundations. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College and Partners Establish Global Network to Transform Higher Education". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "Open Society Foundations Invest $100 Million in Bard College: Strengthening the Global Network". Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Susan (April 1, 2021). "George Soros Is Giving $500 Million To Bard College". Forbes. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "ICP-Bard MFA". May 16, 2016. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Bloomberg (November 10, 2006). "Marieluise Hessel Builds a Museum at Bard for Her Collection". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "Bard Prison Initiative". Bard.edu. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Maximum Security Education". CBS News. April 15, 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ "Bard College - Bard Fiction Prize". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Hannah Arendt Center Archived August 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, January 5, 2018

- ^ Palestinian Campus Looks to East Bank (of Hudson) Archived January 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, February 14, 2009

- ^ AlQuds Bard Requirements Archived March 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, March 29, 2017

- ^ Eichler, Jeremy (September 12, 2011). "After Longy-Bard merger, a music school peers into its future". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ "History". Bard College Berlin. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ Mark, Primoff (June 24, 2013). "Bard College and Soochow University in China Agree to Comprehensive Partnership, including the Creation of a Joint Music Program, Student Exchange, and the Bard College Liberal Arts Academy in Soochow University". News & Events. Bard College. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Bard College Offers Unique Admission Program for High School Juniors". www.bard.edu. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Associated Collegiate Press. "ACP Best of Show Winners". Studentpress.org. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ "The Bard Free Press". August 26, 2007. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ College, Bard. "Bard Student Clubs at Bard College". studentactivities.bard.edu. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "About WXBC Archived December 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine", WXBC. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ CMJ College Radio Awards Nominees Archived May 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine College Music Journal November 16, 2006

- ^ "SMOG". Student.bard.edu. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2011.

- ^ "Club Sports". Bard College Athletics. Archived from the original on August 26, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "Remembering Disney Legend Richard M. Sherman". The Walt Disney Company. May 25, 2024. Archived from the original on May 30, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ "Chevy Chase Movies and Shows". Apple TV. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ "Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. November 25, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ "A Fashionable Life: Jacqui Getty". May 1, 2007. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Rebecca Flint Marx (2016). "Todd Haynes – Biography". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ "Sadie Benning". LANDMARKS. University of Texas at Austin. August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Hemon, Aleksandar (September 3, 2012). "The Wachowskis, Beyond the Matrix". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Sharpsteen, Bill (October 29, 2000). "EYE OF THE BEHOLDER". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Rosen, Steven (November 16, 2006). "Want to spoof Purim and the Oscars? Be our Guest!". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. 21 (39). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ "The Beats within". Billysteinberg.com. September 28, 2005.

- ^ "Condition: Critical (David Cote, Time Out New York)". Martin E. Segal Theatre Center. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (October 24, 2016). "Adam Conover Turns a Skeptical Eye to the Presidential Campaign". The New York Times.

- ^ Ito, Robert (May 7, 2019). ""Sometimes out of something awful something wonderful happens"". The California Sunday Magazine. Retrieved January 11, 2022.

- ^ "Designer Profile: Tom Ford | Mens Fashion Magazine". October 8, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Bard College Alumnus Ronan S. Farrow '04 Awarded Prestigious Rhodes Scholarship" (Press release). Bard College. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Wreszin, Michael (1972). The Superfluous Anarchist: Albert Jay Nock, Brown University Press, p. 11.

- ^ Coyle, Jake (May 4, 2012). "Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys dies at 47". Boston.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Kazanjian, Dodie (April 13, 2020). "Artist Tschabalala Self Upends Our Perception of the Female Form". Vogue. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Inside Frances Bean Cobain's Unique Private World With Riley Hawk". E! Online. September 30, 2024. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Fultz, Lucille P. (2003). Toni Morrison: Playing with Difference. University of Illinois Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0252028236.

- ^ Bird, David (December 4, 1975a). "Hannah Arendt, Political Scientist Dead". The New York Times (Obituary). Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ "Mary McCarthy: A Biographical Sketch". Special Collections: Mary McCarthy – A Biographical Sketch. Vassar College Libraries. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ "Nathan Thrall". Nathan Thrall. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Richard Teitelbaum, Experimentalist With An Earth-Spanning Ear, Dead At 80". NPR.org.

- ^ "Mary Lee Settle profile". Wvwc.edu. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "BARD COLLEGE PRESENTS EXILES ON EXILE Panel Will Feature Renowned Authors and Bard Faculty Members Chinua Achebe, Norman Manea, and Andre Aciman | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Nobel Prize–Winning Author Orhan Pamuk is Writer in Residence | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Ezenwa-Ohaeto (1997). Chinua Achebe: A Biography. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-253-33342-1.

- ^ Relations, Bard Public. "Esteemed Filmmaker Charles Burnett Joins Bard College Faculty | Bard College Public Relations". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Dance Bill T. Jones Dance Company Partnership at Bard College". dance.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Alexander Soros". www.opensocietyfoundations.org. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Stephen Shore". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "An-My Le". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Neil Gaiman". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Jeffrey Gibson". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Gilles Peress". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "John Ryle". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Tan Dun". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Walid Raad". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Daniel Mendelsohn". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Hua Hsu". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Kobena Mercer". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Joseph O'Neill". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Ian Buruma". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Judy Pfaff". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Bard Professor Who Was Named Composer of the Year". Hudson Valley Magazine. January 21, 2020. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ "Joan Tower". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Walter Russell Mead". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Nayland Blake". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Nuruddin Farah". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ College, Bard. "Mona Simpson". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "People". www.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Masha Gessen". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Kelly Reichardt". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "The Novel, 'The Vixen,' Explores The Moral Ambiguity Of 1950s America". NPR.org. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Francine Prose". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Susan Weber - Bard Graduate Center". www.bgc.bard.edu. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Lauren Cornell". CCS Bard. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Ann Lauterbach". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Valeria Luiselli". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Tschabalala Self". Bard College. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Bard College

- History of Columbia University

- 1860 establishments in New York (state)

- Universities and colleges established in 1860

- Liberal arts colleges in New York (state)

- Red Hook, New York

- Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

- Universities and colleges affiliated with the Episcopal Church (United States)

- Universities and colleges in Dutchess County, New York

- Private universities and colleges in New York (state)

- Tourist attractions in Dutchess County, New York

- Organizations listed in Russia as undesirable