Camden County, Georgia

Camden County | |

|---|---|

Camden County Courthouse in Woodbine | |

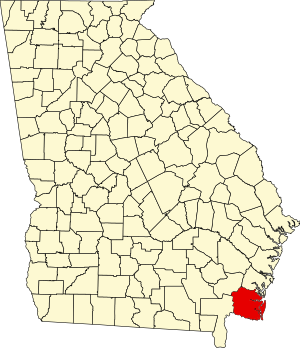

Location within the U.S. state of Georgia | |

Georgia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°55′N 81°38′W / 30.92°N 81.64°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1777 |

| Named for | Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden |

| Seat | Woodbine |

| Largest city | Kingsland |

| Area | |

• Total | 782 sq mi (2,030 km2) |

| • Land | 613 sq mi (1,590 km2) |

| • Water | 169 sq mi (440 km2) 21.6% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 54,768 |

| • Density | 89.3/sq mi (34.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | camdencountyga.gov |

Camden County is a county located in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Georgia. According to the 2020 census, its population was 54,768.[1] Its county seat is Woodbine,[2] and the largest city is Kingsland. It is one of the original counties of Georgia, created February 5, 1777. It is the 11th-largest county in the state of Georgia by area, and the 41st-largest by population.[3][4]

Camden County comprises the Kingsland, Georgia Micropolitan Statistical Area (μSA), formerly known as the St. Marys, Georgia μSA, which is included in the Jacksonville—Kingsland—Palatka, Florida–Georgia Combined Statistical Area.[5]

History

[edit]Colonial period

[edit]The first recorded European to visit what is today Camden County was Captain Jean Ribault of France in 1562. Ribault was sent out by French Huguenots to find a suitable place for a settlement. Ribault named the rivers he saw the Seine and the Some, known today as the St. Marys and Satilla Rivers. Ribault described the area as, "Fairest, fruitfulest and pleasantest of all the world."[6]

In 1565, Spain became alarmed by the French settlements and sent out a large force to take over and settle the area. During that time, the Spaniards attempted to convert the Native Americans to Catholicism. At least two missions operated on Cumberland Island, ministering to the Timucuan people, who had resided on the island for at least 4,000 years.

Competing British and Spanish claims to the territory between their respective colonies of South Carolina and Florida was a source of international tension, and the colony of Georgia was founded in 1733 in part to protect the British interests. The Spanish theoretically lost their claim to the territory in 1742 after the Battle of Bloody Marsh (on St. Simons Island). However, settlement south of the Altamaha River (what is now Glynn and Camden Counties) was discouraged by both the British and Spanish governments. One group of settlers led by Edmund Gray sparked Spanish military action after settling on the Satilla River in the 1750s near present-day Burnt Fort, and were subsequently disbanded by the Royal Governor John Reynolds.[7]

General Oglethorpe was at Cumberland Island when Tomochichi gave the barrier island its name. Later, he erected a hunting lodge on Cumberland named Dungeness, which was the predecessor of the famous Greene and Carnegie Dungeness Mansions. He also founded Fort St. Andrews on the north end of Cumberland Island, as well as a strong battery, Fort Prince Williams, on the south end. Fort Prince Williams commanded the entrance to the St. Marys River but had become a ruin by the Revolutionary War.

In 1763, Spain, under a treaty of peace with Great Britain, ceded Florida to the British. After this, the boundaries of Georgia were extended from the Altamaha (now the southern boundary of McIntosh County) to the St. Marys River (the current southern boundary of Camden). In 1765, four parishes were laid out between the Altamaha and St. Marys Rivers. These were St. Davids, St. Patricks, St. James, and the parishes of St. Marys and St. Thomas.

Early American era

[edit]Largely due to security issues arising from proximity to powerful Indian groups and British Florida, Georgia was the last colony to join in the War for Independence in 1775. In the Georgia Constitution of 1777 St. Thomas and St. Marys Parishes were formed into Camden County, named for Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden in England, a supporter of American independence. Originally Camden County was larger and also included parts of present-day Ware, Brantley, and Charlton Counties, which were re-designated in the nineteenth century.

Also under the 1777 state constitution, Glynn County and Camden County had limited and restricted representation in the new patriotic Georgia government due to their extreme "state of alarm" throughout the war.[8] Between 1776 and 1778 Camden County saw the construction of numerous forts, three failed American campaigns against the British at St. Augustine, and numerous depredations by raiders of various allegiance. One of the most notorious of these raiders was Daniel McGirth.[9] A significant loyalist faction existed in Camden County, headed by the brothers of Royal Governor James Wright, Charles and German Wright. They built a fort on the St. Marys River in 1775 to protect their lands and chattel during the war after repeated attacks by patriot banditti. Wright's Fort became a rendezvous for a group of loyalists called the "Florida Rangers". Two skirmishes were fought by Loyalist and Continental forces over Wright's Fort, and both times American troops failed to rout the Loyalists from the area. Finally, retreating British soldiers burned it down in 1778. The Americans rebuilt it when they invaded East Florida, and then burned it down to prevent it falling into enemy hands. The archaeological site was rediscovered in 1975.[10]

The primary economic enterprise of the county was rice planting, particularly along the Satilla River. Sea Island cotton was grown on Cumberland Island, and short-staple cotton was grown on the mainland along with sugar cane. Various forest products including turpentine and timber were produced, mainly for consumption in the naval industry and the West Indies.[11] Camden County also served as a hub of backcountry trade with American settlers and various Indian groups, and as a shipyard and shipping center centered around the town of St. Marys. The land in Camden County was owned by fewer than 300 people throughout the colonial and antebellum eras. Most of the white population worked in trades or as tenant farmers, while nearly all black residents were slaves. Until the 1840s (and increasingly strict black codes), Camden County had a small population of free black workers, mainly involved in day labor or maritime industry.

Camden County was the site of many trading posts with the Native Americans, who by the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries consisted mainly of people of the Creek Nation. From America's earliest years and even after Indian Removal in the 1830s, the county was a site of significant conflict between settlers and Indians, leading to a small series of local Indian wars, and displacement of both Indian and local American refugees. An important step towards establishing boundaries in the Early Federal period came with the Treaty of Colerain which was signed on June 29, 1796, on the St. Marys between United States agents and the Creeks.

Many men from Camden County volunteered to fight under John Houstoun McIntosh, a wealthy landowner in the region, during the Patriot War in Florida in 1811. These men would go on to help capture the town of Fernandina, Florida.[12]

On January 15, 1815, British troops led by Sir George Cockburn landed on Cumberland Island. Their goal was to attack the fort at Point Peter. They quickly overwhelmed the small American forced and took Ft. Point Peter easily. After the skirmish, British soldiers occupied the county through February. They raided the town of St. Marys, as well as many plantations and smaller settlements. Although New Orleans was the last major battle of the war, the skirmish at Point Peter happened even later, almost a month after the Treaty of Ghent had been signed. The British occupation of Camden County led to the liberation of an estimated 1,485 slaves from Georgia and Florida.[13]

Camden County was on an international border until the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 between the United States and Spain, making the Florida provinces American territory.

Civil War and Reconstruction

[edit]At the beginning of the Civil War, the population was 5,482 of which 1,721 were white. During the war, many of the county's civilians moved farther inland, particularly to Centerville and Trader's Hill on the St. Marys River in Charlton County. The inhabitant's fears were realized when the town of St. Marys was attacked by United States Navy.[citation needed] At least one federal party to "carry off" slaves was met by armed resistance on White Oak Creek off the Satilla River.[14]

Camden County organized four volunteer companies: the Camden Chasseurs, St. Marys Volunteers Guard, Camden Rifles, and Camden County Guards.[15]

Camden County land fell under Sherman's Special Field Order No. 15. which dictated the distribution of parcels of land to freedmen. However, by 1868, Camden County's freedmen found themselves dispossessed of land they had lived and worked on since emancipation or earlier. Confiscated lands were returned to former landowners.[16] During the first years of Reconstruction, Republican candidates and many local blacks were able to gain political victories. The first Democratic victory in the county after the war went to Ray Tompkins. This signaled a return to a white political majority and the end of the Reconstruction Era concurrent with the statewide Democratic victory in 1870.[17]

Since the 1830s

[edit]Earlier plans for railways in the area dated back to the 1830s, but construction was never begun. In 1893, Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad built a Savannah-Jacksonville line through Camden County. In 1923 the county seat of Camden County was moved from St. Marys to Woodbine, a reflection of the shift from the water transportation to railways. In 1927, U.S. Route 17 was constructed through Woodbine and Kingsland.[11]

From 1917 to 1937, a pogy plant producing oil for Procter & Gamble and fertilizer for the Southern Fertilizer and Chemical Company was one of the major economic activities of the area. The layoffs from the pogy plant found relief when the Gilman Paper Company came to the county in 1939. The company was sold to Durango Paper Co. in 1999, and went out of business in 2002, resulting in 900 workers losing their jobs.[18]

In 1965, Thiokol Chemical launched a 13-foot (4.0 m)-diameter, 3,000,000-pound-force (13,000 kN)-thrust rocket from their chemical plant in the eastern part of the county.[19] On February 3, 1971, a fire and explosion occurred at the plant, located 12 miles southeast of Woodbine. The industrial accident killed 29 workers and seriously injured 50 others.[6]

During World War II, the Georgia State Guard and local Home Guard held bases on Cumberland Island.[11] The island and surrounding waters were also patrolled by the United States Coast Guard.[16] The U.S. Army began to acquire land south of Crooked River in 1954 to build a military ocean terminal to ship ammunition in case of a national emergency. In November 1976, the area of Kings Bay was selected for a submarine base. Soon afterward, the first Navy personnel arrived in the Kings Bay area and started preparations for the orderly transfer of property from the Army to the Navy. Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay not only occupies the former Army terminal land, but several thousand additional acres. Camden County's population grew enormously after the military took an interest in the area, and during the 1980s, was the fourth fastest growing county in the United States.[11]

Cumberland Island National Seashore was established in 1970 to protect and preserve the natural and historic resources of the island. Crooked River State Park was established in 1985.

In 2009, the Camden County Sheriff's Office was ordered by the Justice Department to repay $662,000 of improperly spent funds seized from alleged criminals before it would be allowed to participate in the Justice Department's equitable sharing program. Items that were determined to have been purchased by the Camden County Sheriff's Department improperly included a Dodge Viper purchased for approximately $90,000 which the Sheriff's Office intended to use in anti-drug programs.[20][21]

In 2012, the Camden County Joint Development Authority began considering developing a spaceport for both horizontal and vertical spacecraft operations. Options included moving the St. Marys' airport to the Atlantic coastal site[22] which had previously been used for a rocket launch in 1965.[19] In 2013, the authority contracted for an Environmental Impact Statement to be completed on 200 acres (81 ha) of authority-owned land, part of a larger 4,200 acres (1,700 ha) site, in order to build a commercial launch site.[23] As of September 2014[update], the county was investigating options to purchase 11,000 acres (4,500 ha) of land from landowners who own the land formerly occupied by Thiokol Chemical and Bayer CropScience at Harrietts Bluff. If an agreement is reached with landowners, then another 18-month-long environmental impact process could begin on the larger parcel of land. Georgia state legislators would likely offer tax incentives for commercial development in the project. If development were to proceed, the earliest launch possible would have been in 2018, according to the 2014 projections.[19][needs update]

In June 2015, the Camden board decided to formally advance the Spaceport Camden project by initiating an FAA Environmental Impact Assessment of the 4000+ acre facility.[24][needs update]

Geography

[edit]According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 782 square miles (2,030 km2), of which 613 square miles (1,590 km2) is land and 169 square miles (440 km2) (21.6%) is water.[25]

The bulk of Camden County's central and western area, from an east–west line running through Waverly in the north to a line running from Charlton County northeast to St. Andrew Sound, is located in the Satilla River sub-basin of the St. Marys-Satilla basin. The area north of Waverly, as well as from west of Kingsland east to the coast of Cumberland Island, is located in the Cumberland-St. Simons sub-basin of the St. Marys-Satilla River basin. Camden County's southern border area, in a line from Charlton County to St. Marys, is located in the St. Marys River sub-basin of the same St. Marys-Satilla basin.[26]

The 1898 Georgia hurricane which made landfall on Cumberland Island in Camden County was the strongest hurricane to hit the state of Georgia within recorded history.[27]

Major highways

[edit] I-95 (Interstate 95)

I-95 (Interstate 95) US 17

US 17 SR 25

SR 25 SR 25 Spur

SR 25 Spur SR 40

SR 40 SR 40 Spur

SR 40 Spur SR 110

SR 110 SR 252

SR 252 SR 405 (unsigned designation for I-95)

SR 405 (unsigned designation for I-95)

Adjacent counties

[edit]- Glynn County (north)

- Nassau County, Florida (south)

- Charlton County (west)

- Brantley County (northwest)

National protected area

[edit]Communities

[edit]Cities

[edit]Census-designated place

[edit]Unincorporated communities

[edit]- Dover Bluff

- Hopewell

- Spring Bluff

- Waverly

- White Oak

- Bullhead Bluff

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 305 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,681 | 451.1% | |

| 1810 | 3,941 | 134.4% | |

| 1820 | 4,342 | 10.2% | |

| 1830 | 4,578 | 5.4% | |

| 1840 | 6,075 | 32.7% | |

| 1850 | 6,319 | 4.0% | |

| 1860 | 5,420 | −14.2% | |

| 1870 | 4,615 | −14.9% | |

| 1880 | 6,183 | 34.0% | |

| 1890 | 6,178 | −0.1% | |

| 1900 | 7,669 | 24.1% | |

| 1910 | 7,690 | 0.3% | |

| 1920 | 6,969 | −9.4% | |

| 1930 | 6,338 | −9.1% | |

| 1940 | 5,910 | −6.8% | |

| 1950 | 7,322 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 9,975 | 36.2% | |

| 1970 | 11,334 | 13.6% | |

| 1980 | 13,371 | 18.0% | |

| 1990 | 30,167 | 125.6% | |

| 2000 | 43,664 | 44.7% | |

| 2010 | 50,513 | 15.7% | |

| 2020 | 54,768 | 8.4% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 58,118 | [28] | 6.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] 1790-1880[30] 1890-1910[31] 1920-1930[32] 1930-1940[33] 1940-1950[34] 1960-1980[35] 1980-2000[36] 2010[37] 2020[38] | |||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[39] | Pop 2010[37] | Pop 2020[38] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 31,975 | 35,977 | 37,203 | 73.23% | 71.22% | 67.93% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 8,719 | 9,621 | 9,497 | 19.97% | 19.05% | 17.34% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 195 | 230 | 185 | 0.45% | 0.46% | 0.34% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 429 | 706 | 845 | 0.98% | 1.40% | 1.54% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 32 | 70 | 66 | 0.07% | 0.14% | 0.12% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 70 | 72 | 325 | 0.16% | 0.14% | 0.59% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 659 | 1,247 | 2,989 | 1.51% | 2.47% | 5.46% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,585 | 2,590 | 3,658 | 3.63% | 5.13% | 6.68% |

| Total | 43,664 | 50,513 | 54,768 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 54,768 people, 19,338 households, and 14,380 families residing in the county. Among the 2020 population, its racial and ethnic makeup was 67.93% non-Hispanic white, 17.34% African American, 0.34% Native American, 1.54% Asian alone, 0.12% Pacific Islander American, 6.05% multiracial, and 6.68% Hispanic or Latino of any race.[40]

Education

[edit]Camden is home to one comprehensive[clarification needed] public high school (with a separate center for ninth graders), two middle schools, nine elementary schools and an alternative school. The system serves approximately 9,600 students. The school board is run by the following members:[41]

- Superintendent of Schools - Dr. Will Hardin

- Assistant Superintendent - Dr. Jonathan Miller

- Assistant Superintendent - Dr. Rebecca Gillette

Camden County High School is the single public high school in Camden County, offering a comprehensive curriculum (9–12) with a variety of classes for both College Preparatory and Career Technology Preparatory. The high school campus is one of the largest in the state of Georgia. It consists of a main building (10-12 building) as well as a ninth-grade center that holds two additional hallways, one gymnasium, one cafeteria, and one media center. The school has also recently constructed an additional building consisting of classrooms, conference rooms, and a large weight room. The school offers AP classes and joint enrollment with College of Coastal Georgia and the Valdosta State University Kings Bay Campus. The school is part of the Georgia High School Association and is classified as a "AAAAAAA" or "7A" school in Region 1. In 2003, the Wildcats won the Georgia 5A Football State Championship by defeating Valdosta High School. In 2008, the Wildcats won their second 5A State Football Championship by defeating Peachtree Ridge High School. In 2009, the Wildcats won their third 5A State Football Championship by defeating Northside (Warner Robins).

Politics

[edit]| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2024 | 17,819 | 67.51% | 8,405 | 31.85% | 169 | 0.64% |

| 2020 | 15,249 | 64.35% | 7,967 | 33.62% | 482 | 2.03% |

| 2016 | 12,310 | 64.56% | 5,930 | 31.10% | 829 | 4.35% |

| 2012 | 11,343 | 62.84% | 6,377 | 35.33% | 330 | 1.83% |

| 2008 | 10,502 | 61.39% | 6,482 | 37.89% | 124 | 0.72% |

| 2004 | 9,488 | 66.85% | 4,637 | 32.67% | 68 | 0.48% |

| 2000 | 6,371 | 62.96% | 3,636 | 35.93% | 112 | 1.11% |

| 1996 | 4,222 | 49.75% | 3,644 | 42.94% | 620 | 7.31% |

| 1992 | 3,517 | 46.45% | 2,952 | 38.99% | 1,103 | 14.57% |

| 1988 | 2,913 | 57.68% | 2,090 | 41.39% | 47 | 0.93% |

| 1984 | 2,841 | 56.76% | 2,164 | 43.24% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1980 | 1,439 | 32.39% | 2,924 | 65.81% | 80 | 1.80% |

| 1976 | 995 | 25.15% | 2,962 | 74.85% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1972 | 2,380 | 75.97% | 753 | 24.03% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 751 | 19.33% | 1,146 | 29.50% | 1,988 | 51.17% |

| 1964 | 1,802 | 51.56% | 1,693 | 48.44% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 950 | 41.83% | 1,321 | 58.17% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 1,014 | 46.26% | 1,178 | 53.74% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 619 | 32.51% | 1,285 | 67.49% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 208 | 19.17% | 552 | 50.88% | 325 | 29.95% |

| 1944 | 76 | 12.03% | 556 | 87.97% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 60 | 9.60% | 564 | 90.24% | 1 | 0.16% |

| 1936 | 53 | 9.28% | 515 | 90.19% | 3 | 0.53% |

| 1932 | 49 | 10.45% | 417 | 88.91% | 3 | 0.64% |

| 1928 | 267 | 49.35% | 274 | 50.65% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 1 | 0.57% | 172 | 98.29% | 2 | 1.14% |

| 1920 | 14 | 8.43% | 152 | 91.57% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 4 | 1.54% | 251 | 96.91% | 4 | 1.54% |

| 1912 | 2 | 0.82% | 238 | 97.94% | 3 | 1.23% |

Notable people

[edit]- James Seagrove: appointed Creek Indian Agent by the federal government and Superintendent of Creek Indian Affairs in 1789. Also a local trader associated with Trader's Hill and founder of St. Marys.[43][44]

- Duncan Lamont Clinch: After serving in the Seminole Wars, partially in Camden County, Clinch retired to planting near Jefferson on the Satilla River, and later began his political career.[45]

- Thomas Buckingham Smith: Born on Cumberland Island in 1810, Smith was a diplomat, antiquarian, and scholar. Notable Spanish translator and author of works on southern Native Americans.[46]

- John Floyd (October 3, 1769 – June 24, 1839): was an American politician and brigadier general in the First Brigade of Georgia Militia. He was a member of the Georgia House of Representatives, as well as the US House of Representatives.

- Charles Rinaldo Floyd (1797-1845): led the first U.S. campaign into the Okefenoke Swamp during the Seminole Wars. The Floyds were the largest planting family in Camden County.[47]

- Catherine Littlefield Greene: Wife of General Nathaniel Greene. Lived on Cumberland Island and built the county's largest antebellum home, Dungeness.[48][49]

- Travis Taylor: American former college and professional football player who was a wide receiver in the National Football league (NFL) for eight seasons during the 2000s. Taylor played college football for the University of Florida. A first-round pick in the 2000 NFL draft, he played professionally for the Baltimore Ravens, Minnesota Vikings, Oakland Raiders and St. Louis Rams.[50]

- Stump Mitchell: American football coach and former professional player. He served as head football coach at Morgan State University from 1996 to 1998 and Southern University from 2010 to 2012, compiling an overall college football record of 14–42. Mitchell played collegiately at The Citadel and thereafter was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals of the National Football League (NFL). He was a running back and return specialist for the Cardinals from 1981 to 1989.

- Ryan Seymour: American football offensive guard for the New York Giants of the National Football League (NFL). He was drafted by the Seattle Seahawks in the seventh round of the 2013 NFL draft, and has also played for the San Francisco 49ers and Cleveland Browns. He played college football for Vanderbilt.[51]

- Alicia Patterson: Founder and editor of Newsday. While not from Camden County by birth, her remains are interred at her private hunting lodge in Kingsland.[52]

- Jarrad Davis: Former linebacker for the Camden County Wildcats, the University of Florida, and current linebacker for the Detroit Lions[53]

- Jason Spencer: former State Representative for district 180 in the Georgia House of Representatives from 2011 to 2018, is a longtime resident of the center of the district, Woodbine.

- William J. Hardee, Confederate general

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Camden County, Georgia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Georgia Land area in square miles, 2010 by County". IndexMundi. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Georgia Population by County". IndexMundi. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ "Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Guidance on the Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Executive Office of the President. July 21, 2023. p. 135. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ a b " Archived November 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Camden County History" Archived November 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Our Georgia History

- ^ Hamer, Marguerite Bartlett. "Edmund Gray and His Settlement at New Hanover." The Georgia Historical Quarterly, ISSN 0016-8297, 03/1929, Volume 13, Issue 1, pp. 1 - 12

- ^ Revolutionary Records of Georgia. Volume 1. page 285.

- ^ Martha Condray Searcy. The Georgia-Florida Contest in the American Revolution. University of Alabama Press, 1985. See also, Wilbur H. Siebert, "Privateering in Florida Waters and Northwards in the American Revolution". Florida Historical Quarterly XXII. 1943. 62-73.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d Reddick, Margurite. Camden's Challenge. WH Wolfe Associates, Alpharetta, Georgia, 1994.

- ^ Patrick, Rembert (1954). Florida Fiasco: Rampant Rebels on the Georgia-Florida Border 1810-1815. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 57.

- ^ "Forgotten Invasion". Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ James Vocelle. History of Camden County. 97.

- ^ The Southern Recorder. April 31, 1861. Milledgeville Historic Newspapers Archive: Georgia Historic Newspapers http://milledgeville.galileo.usg.edu/milledgeville/view?docId=news/srw1861/srw1861-0065.xml&query=Camden&brand=milledgeville-brand Archived October 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Bullard. Cumberland Island: A History. University of Georgia Press 2001.

- ^ Vocelle, James. History of Camden County Georgia.

- ^ "Durango paper mill closing, 900 workers lose jobs | Online Athens". April 6, 2016. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c Heglund, Emily (September 2014). "Camden spaceport could be 'turning point' for Ga". Tribune & Georgian. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "Sheriff Under Scrutiny over Drug Money Spending". NPR.org. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Dickson, Terry. "Camden County works way back into federal seized assets program". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Rush, Johna Strickland (November 15, 2012). "Spaceport could land in Camden". Tribune & Georgian. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Perez-Trevino, Emma (January 6, 2014). "Brownsville, SpaceX await FAA ruling". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved January 10, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^

"Camden County Board of Commissioners Approves Option Agreement for Real Estate". Spaceport Camden. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

On June 3, 2015, The Board of County Commissioners unanimously approved an option agreement to purchase 4,011 acres, more or less. The subject property was the former location where the world's most powerful rocket motor was test fired in the 1960s. The county will be commencing soon the next milestone of the project whereby the Federal Aviation Administration prepares an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to address the potential environmental impacts of constructing and operating a commercial launch site in Camden County, Georgia. "This exciting announcement advances the project forward and aligns with the county's vision of developing a world-class spaceport," stated Steve Howard, County Administrator.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission Interactive Mapping Experience". Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2015.

- ^ @philklotzbach (October 10, 2018). "The last major (Category 3+)..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- ^ "Decennial Census of Population and Housing by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1880 Census Population by Counties 1790-1800" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1880.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1910.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1930.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1940.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Georgia -" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1950.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1980.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - Georgia" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2000.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Camden County, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Camden County, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Camden County, Georgia". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "CAMDEN COUNTY SCHOOLS ORGANIZATION 2017-2018" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2018.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "James Seagrove b. 1747 Colerain, Londonderry, Ireland d. 16 Jul 1812 St. Marys, Camden, GA: Georgia Society SAR Graves Registry". gasocietysar.org. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Founders Online: To George Washington from James Seagrove, 5 July 1792". Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "A Guide to the General Duncan Lamont Clinch Family Papers". www.library.ufl.edu. Clinch, Duncan Lamont Jr., Clinch, John Houstoun McIntosh. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Guide to the Buckingham Smith papers and collected materials, 1529-1941, n.d." dlib.nyu.edu. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Charles Floyd. New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Catharine Greene (1755-1814)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Catherine Greene | History of American Women". History of American Women. March 22, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ "Travis Taylor Past Stats". Database Football. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "Vanderbilt Football: Ryan Seymour". vucommodores.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Robert, Keeler (1990). Newsday: A Candid History of the Respectable Tabloid. Morrow. p. 314. ISBN 978-1-55710-053-5.

- ^ "Jarrad Davis". NFL.com. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Camden County website

- "Camden County" New Georgia Encyclopedia Archived October 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine