Acanthocyte

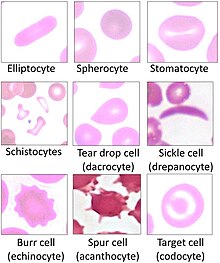

Acanthocyte (from the Greek word ἄκανθα acantha, meaning 'thorn'), in biology and medicine, refers to an abnormal form of red blood cell that has a spiked cell membrane, due to thorny projections.[1][2] A similar term is spur cells. Often they may be confused with echinocytes or schistocytes.

Acanthocytes have coarse, irregularly spaced, variably sized crenations, resembling many-pointed stars. They are seen on blood films in abetalipoproteinemia,[3] liver disease, chorea acanthocytosis, McLeod syndrome, and several inherited neurological and other disorders such as neuroacanthocytosis,[4] anorexia nervosa, infantile pyknocytosis, hypothyroidism, idiopathic neonatal hepatitis, alcoholism, congestive splenomegaly, Zieve syndrome, and chronic granulomatous disease.[5]

Usage

[edit]Spur cells may refer synonymously to acanthocytes,[6] or may refer in some sources to a specific subset of 'extreme acanthocytes' that have undergone splenic modification whereby additional cell membrane loss has blunted the spicules and the cells have become spherocytic ('spheroacanthocyte'), as seen in some patients with severe liver disease.[7]

Acanthocytosis can refer generally to the presence of this type of crenated red blood cell, such as may be found in severe cirrhosis or pancreatitis,[6] but can refer specifically to abetalipoproteinemia, a clinical condition with acanthocytic red blood cells, neurologic problems and steatorrhea.[8] This particular cause of acanthocytosis (also known as abetalipoproteinemia, apolipoprotein B deficiency, and Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome) is a rare, genetically inherited, autosomal recessive condition due to the inability to fully digest dietary fats in the intestines as a result of various mutations of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) gene.[9]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Acanthocytes arise from either alterations in membrane lipids or structural proteins. Alterations in membrane lipids are seen in abetalipoproteinemia and liver dysfunction. Alteration in membrane structural proteins are seen in neuroacanthocytosis and McLeod syndrome.

In liver dysfunction, apolipoprotein A-II deficient lipoprotein accumulates in plasma causing increased cholesterol in RBCs. This causes abnormalities of membrane of RBC causing remodeling in spleen and formation of acanthocytes.

In abetalipoproteinemia, there is deficiency of lipids and vitamin E causing abnormal morphology of RBCs.[10]

Differential diagnoses

[edit]

The diagnosis of acanthocytosis should be differentiated from: acute or chronic anemia, hepatitis A, B, and C, hepatorenal syndrome, hypopituitarism, malabsorption syndromes, and malnutrition.[11]

Acanthocytosis secondary to malnourishment, such as anorexia nervosa and cystic fibrosis, remits with resolution of the nutritional deficiency.[12] Acanthocyte-like cells may be found in hypothyroidism, after splenectomy, and in myelodysplasia.[12]

Acanthocytes should be distinguished from echinocytes, which are also called 'burr cells', which although crenated are dissimilar in that they have multiple, small, projecting spiculations at regular intervals on the cell membrane.[7][12] Burr cells usually imply uremia, but are seen in many conditions, including mild hemolysis in hypomagnesemia and hypophosphatemia, hemolytic anemia in long-distance runners, and pyruvate kinase deficiency.[11] Burr cells can also arise in vitro due to elevated pH, blood storage, ATP depletion, calcium accumulation, and contact with glass.[11] Acanthocytes should also be distinguished from keratocytes, also called 'horn cells' which have a few very large protuberances.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "acanthocyte" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Wrongdiagnosis / Acanthocytosis Retrieved on October 12, 2009

- ^ Cooper RA, Durocher JR, Leslie MH (July 1977). "Decreased fluidity of red cell membrane lipids in abetalipoproteinemia". J. Clin. Invest. 60 (1): 115–21. doi:10.1172/JCI108747. PMC 372349. PMID 874076.

- ^ Rampoldi L, Danek A, Monaco AP (2002). "Clinical features and molecular bases of neuroacanthocytosis". J Mol Med. 80 (8): 475–91. doi:10.1007/s00109-002-0349-z. PMID 12185448. S2CID 21615621.

- ^ "Acanthocytosis". Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b Hillman, RS; Ault, KA; Leporrier, M; Rinder, HM. (2011). Hematology in Clinical Practice (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162699-6.

- ^ a b Mentzer WC. Spiculated cells (echinocytes and acanthocytes) and target cells. UpToDate (release: 20.12- C21.4) [1]

- ^ Longo, D; Fauci, AS; Kasper, DL; Hauser, SL; Jameson, JL; Loscalzo J. (2012). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07174889-6.

- ^ Haldeman-Englert, C; Zieve, D. (August 4, 2011). "Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome". Pub Med Health. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Alarcon, Pedro A de (2024-01-17). "Acanthocytosis: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape Reference. Retrieved 2024-06-26.

- ^ a b c de Alarcon PA (Nov 30, 2011). "Acanthocytosis".

- ^ a b c d Hoffman, R; Benz, EJ; Silberstein, LE; Heslop, H; Weitz J; Anastasi, J. (2012). Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice (6th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-2928-3.

External links

[edit]- Acanthocyte: Presented by the University of Virginia

- Acanthocytes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)