Grenada

Grenada | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Ever Conscious of God We Aspire, Build and Advance as One People"[2] | |

| Anthem: "Hail Grenada" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | St. George's 12°03′N 61°45′W / 12.050°N 61.750°W |

| Official languages | |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2020[5]) | |

| Religion (2020)[6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Grenadian[7] |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Cécile La Grenade | |

| Dickon Mitchell | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 3 March 1967 | |

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 7 February 1974 |

| 13 March 1979 | |

• Constitution Restoration | 4 December 1984 |

| Area | |

• Total | 348.5 km2 (134.6 sq mi) (185th) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 124,610[8][9] (179th) |

• Density | 318.58/km2 (825.1/sq mi) (45th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | high (73rd) |

| Currency | East Caribbean dollar (XCD) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +1-473 |

| ISO 3166 code | GD |

| Internet TLD | .gd |

Grenada (/ɡrəˈneɪdə/ grə-NAY-də; Grenadian Creole French: Gwenad, [ɡweˈnad]) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The southernmost of the Windward Islands, Grenada is directly south of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and about 100 miles (160 km) north of Trinidad and the South American mainland.

Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Petite Martinique, and several small islands which lie to the north of the main island and are a part of the Grenadines. Its size is 348.5 square kilometres (134.6 sq mi), with an estimated population of 114,621 in 2024.[12] Its capital is St. George's.[12] Grenada is also known as the "Island of Spice" due to its production of nutmeg and mace crops.[13]

12°07′N 61°40′W / 12.117°N 61.667°W

Before the arrival of Europeans in the Americas, Grenada was inhabited by the indigenous peoples from South America.[14] Christopher Columbus sighted Grenada in 1498 during his third voyage to the Americas.[12] Following several unsuccessful attempts by Europeans to colonise the island due to resistance from resident Island Caribs, French settlement and colonisation began in 1649 and continued for the next century.[15] On 10 February 1763, Grenada was ceded to the British under the Treaty of Paris. British rule continued until 1974 (except for a brief French takeover between 1779 and 1783).[16] However, on 3 March 1967, it was granted full autonomy over its internal affairs as an Associated State, and from 1958 to 1962, Grenada was part of the Federation of the West Indies, a short-lived federation of British West Indian colonies.

Independence was granted on 7 February 1974 under the leadership of Eric Gairy, who became the first prime minister of Grenada as a sovereign state. The new country became a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, with Queen Elizabeth II as head of state.[12] In March 1979, the Marxist–Leninist New Jewel Movement overthrew Gairy's government in a bloodless coup d'état and established the People's Revolutionary Government (PRG), headed by Maurice Bishop as prime minister.[17] Bishop was later arrested and executed by members of the People's Revolutionary Army (PRA), which was used to justify a U.S.-led invasion in October 1983. Since then, the island has returned to a parliamentary representative democracy and has remained politically stable.[12] A Governor General represents the Head of State. The country is currently headed by King Charles III, King of Grenada, and 14 other commonwealth realms.

Etymology

[edit]The origin of the name "Grenada" is obscure, but it is likely that Spanish sailors named the island for the Andalusian city of Granada.[12][18] The name "Granada" was recorded by Spanish maps in the 1520s and referred to the islands to the north as Los Granadillos ("Little Granadas");[15] although those named islands were deemed the property of the King of Spain, there are no records to suggest the Spanish ever attempted to settle Grenada.[19] The French maintained the name (as "La Grenade" in French) after settlement and colonisation in 1649.[15] On 10 February 1763, the island of La Grenade was ceded to the British under the Treaty of Paris. The British renamed it "Grenada", one of many place-name anglicisations they made there.[20]

The island was given its first European name by Christopher Columbus who sighted it on his third voyage to the region in 1498 and named it "La Concepción" in honour of the Virgin Mary. It is said that he may have actually named it "Assumpción", but it is uncertain, as he is said to have sighted what are now Grenada and Tobago from a distance and named them both at the same time. However, it became accepted that he named Tobago "Assumpción" and Grenada "La Concepción".[18] The year after, Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci travelled through the region with the Spanish explorer Alonso de Ojeda and mapmaker Juan de la Cosa. Vespucci is reported to have renamed the island "Mayo", although this is the only map where the name appears.[19]

The indigenous Arawak who once lived on the island before the arrival of the Europeans gave the name Camajuya.[21]

History

[edit]Precolumbian history

[edit]Grenada is thought to have been first populated by peoples from South America during the Caribbean Archaic Age, although definitive evidence is lacking. The earliest potential human presence comes from proxy evidence of lake cores, beginning c. 3600 BC.[22] Less ephemeral, permanent villages began c. 100–200.[14] The population peaked between 750 and 1250, with major changes in population afterward, potentially the result of either the "Carib Invasion" (although highly contested),[23] regional droughts, or both.[24]

European arrival

[edit]In 1498, Christopher Columbus was the first European to report sighting Grenada during his third voyage, naming it 'La Concepción', but Amerigo Vespucci may have renamed it 'Mayo' in 1499.[25] Although it was deemed the property of the King of Spain, there are no records to suggest the Spanish attempted to settle. However, various Europeans are known to have passed and both fought and traded with the indigenous peoples there.[15] The first known settlement attempt was a failed venture by the English in 1609, but they were massacred and driven away by the native "Carib" peoples.[16][25][26]

French colony (1649–1763)

[edit]In 1649, a French expedition of 203 men from Martinique, led by Jacques Dyel du Parquet, founded a permanent settlement on Grenada.[16][25][26] They signed a peace treaty with the Carib chief Kairouane, but within months conflict broke out between the two communities.[27][28] This lasted until 1654 when the island was completely subjugated by the French.[29] Warfare continued during the 1600s between the French on Grenada and the Caribs of present-day Dominica and St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

Chocolate was brought to Grenada in 1714 with the introduction of cocoa beans.[30]

The French named their new colony La Grenade, and the economy was initially based on sugar cane and indigo, worked by African slaves.[31] The French established a capital known as Fort Royal (later St. George's). To shelter from hurricanes, the French navy would often take refuge in the capital's natural harbour, as no nearby French islands had a natural harbour to compare with that of Fort Royal. The British captured Grenada in the Seven Years' War in 1762.[25]

British colonial period

[edit]Early colonial period

[edit]

Grenada was formally ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Paris in 1763.[25] The French re-captured the island during the American Revolutionary War, after Comte d'Estaing won the bloody land and naval Battle of Grenada in July 1779.[25] However, the island was restored to Britain with the Treaty of Versailles in 1783.[25] A decade later, dissatisfaction with British rule led to a pro-French revolt in 1795–96 led by Julien Fédon, which was successfully defeated by the British.[32][33]

As Grenada's economy grew, more and more African slaves were forcibly transported to the island. Britain eventually outlawed the slave trade within the British Empire in 1807. Slavery was completely outlawed in 1833, leading to the emancipation of all enslaved by 1838.[25][34] To ease the subsequent labour shortage, migrants from India were brought to Grenada in 1857.[16][26]

Nutmeg was introduced to Grenada in 1843 when a merchant ship called in on its way to England from the East Indies.[16][26] The ship had a small quantity of nutmeg trees on board, which they left in Grenada, and this was the beginning of Grenada's nutmeg industry that now supplies nearly 40% of the world's annual crop.[35]

Later colonial period

[edit]In 1877, Grenada was made a Crown colony. Theophilus A. Marryshow founded the Representative Government Association (RGA) in 1918 to agitate for a new and participative constitutional dispensation for the Grenadian people.[36] Due to Marryshow's lobbying, the Wood Commission of 1921–22 concluded that Grenada was ready for constitutional reform in the form of a modified Crown colony government. This modification granted Grenadians the right to elect five of the 15 Legislative Council members on a restricted property franchise, enabling the wealthiest 4% of adult Grenadians to vote.[37] Marryshow was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1943.[38]

In 1950, Eric Gairy founded the Grenada United Labour Party (GULP), initially as a trade union, which led to the 1951 general strike for better working conditions.[16][26][39] This sparked great unrest, and so many buildings were set ablaze that the disturbances became known as the "sky red" days. On 10 October 1951, Grenada held its first general elections based on universal adult suffrage,[40] with Gairy's party winning six of the eight seats contested.[40]

From 1958 to 1962, Grenada was part of the Federation of the West Indies.[16][25][26] After the federation's collapse, Grenada was granted full autonomy over its internal affairs as an Associated State on 3 March 1967.[25] Herbert Blaize of the Grenada National Party (GNP) was the first Premier of the Associated State of Grenada from March to August 1967. Eric Gairy served as Premier from August 1967 until February 1974.[25]

Post-independence era

[edit]

Independence was granted on 7 February 1974 under the leadership of Eric Gairy, who became the first prime minister of Grenada.[16][25][26] Grenada opted to remain within the Commonwealth, retaining Queen Elizabeth as Monarch, represented locally by a governor-general. Civil conflict gradually broke out between Eric Gairy's government and some opposition parties, including the Marxist New Jewel Movement (NJM).[25] Gairy and the GULP won the 1976 Grenadian general election, albeit with a reduced majority;[25] however, the opposition deemed the results invalid due to fraud and the violent intimidation performed by the so-called 'Mongoose Gang', a private militia loyal to Gairy.[41][42][43]

On 13 March 1979, whilst Gairy was out of the country, the NJM launched a bloodless coup which removed Gairy, suspended the constitution, and established a People's Revolutionary Government (PRG), headed by Maurice Bishop, who declared himself prime minister.[25] His Marxist–Leninist government established close ties with Cuba, Nicaragua, and other communist bloc countries.[25] All political parties except for the New Jewel Movement were banned and no elections were held during the four years of PRG rule.

Invasion by the United States (1983)

[edit]

Coup and execution of Maurice Bishop

[edit]Some years later,[when?] a dispute developed between Bishop and certain high-ranking members of the NJM. Though Bishop cooperated with Cuba and the USSR on various trade and foreign policy issues, he sought to maintain a non-aligned status. Hardline Marxist party members, including communist Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard, deemed Bishop insufficiently revolutionary and demanded that he either step down or enter into a power-sharing arrangement.[citation needed]

On 16 October 1983, Bernard Coard and his wife, Phyllis, backed by the Grenadian Army, led a coup against the government of Maurice Bishop and placed Bishop under house arrest.[25] These actions led to street demonstrations in various parts of the island because Bishop had widespread support from the population. Because Bishop was a widely popular leader, he was freed by impassioned supporters who marched en masse to his guarded residence from a rally in the capital's central square. Bishop then led the crowd to the island's military headquarters to reassert his power. Grenadian soldiers were dispatched in armoured vehicles by the Coard faction to retake the fort. A confrontation between soldiers and civilians at the fort ended in gunfire and panic. Three soldiers and at least eight civilians died in the tumult that also injured 100 others, a school-sponsored study later found in 2000.[44] When the initial shooting ended with Bishop's surrender, he and a group of seven of his closest supporters were taken prisoner and executed by firing squad. Besides Bishop, the group included three of his cabinet ministers, a trade union leader, and three service-industry workers.[45]

After the execution of Bishop, the People's Revolutionary Army (PRA) formed a military Marxist government with General Hudson Austin as chairman. The army declared a four-day total curfew, during which anyone leaving their home without approval would be shot on sight.[46][47]

United States and allied response and reaction

[edit]

US President Ronald Reagan stated that particularly worrying was the presence of Cuban construction workers and military personnel building a 10,000-foot (3,000 m) airstrip on Grenada.[48] Bishop had stated the purpose of the airstrip was to allow commercial jets to land, but some US military analysts argued that the only reason for constructing such a long and reinforced runway was so that it could be used by heavy military transport planes. The contractors, American and European companies, and the EEC, which provided partial funding, all claimed the airstrip did not have military capabilities. Reagan asserted that Cuba, under the direction of the Soviet Union, would use Grenada as a refuelling stop for Cuban and Soviet airplanes loaded with weapons destined for Central American communist insurgents.[49]

The Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), Barbados, and Jamaica all appealed to the United States for assistance.[50] On 25 October 1983, combined forces from the United States and the Regional Security System (RSS) based in Barbados invaded Grenada in an operation codenamed Operation Urgent Fury. The US stated this was done at the behest of Barbados, Dominica[citation needed] and Governor-General Paul Scoon.[51] Scoon had requested the invasion through secret diplomatic channels, but it was not made public for his safety.[52] Progress was rapid, and within four days the Americans had removed the military government of Hudson Austin.

The invasion was criticised by the governments of Britain,[53] Trinidad and Tobago, and Canada. The United Nations General Assembly condemned it as "a flagrant violation of international law" by a vote of 108 to 9, with 27 abstentions.[54][55] The United Nations Security Council considered a similar resolution, which was supported by 11 countries. However, the United States vetoed the motion.[56]

Post-invasion arrests

[edit]After the invasion, the pre-revolutionary Grenadian constitution came into operation once again. Eighteen members of the PRG/PRA were arrested on charges related to the murder of Maurice Bishop and seven others. The 18 included the top political leadership of Grenada at the time of the execution, along with the entire military chain of command directly responsible for the operation that led to the executions. Fourteen were sentenced to death, one was found not guilty, and three were sentenced to 45 years in prison. The death sentences were eventually commuted to terms of imprisonment. Those in prison have become known as the "Grenada 17".[57]

Since 1983

[edit]When US troops withdrew from Grenada in December 1983, Governor-General Scoon appointed an interim advisory council chaired by Nicholas Brathwaite to organise new elections.[58] The first democratic elections since 1976 were held in December 1984, and were won by the New National Party under Herbert Blaize, who served as prime minister until his death in December 1989.[59][60]

Ben Jones briefly succeeded Blaize as prime minister and served until the March 1990 election.[61][62] This election was won by the National Democratic Congress under Nicholas Brathwaite, who served as prime minister until he resigned in February 1995.[63] He was succeeded by George Brizan for a brief period[64] until the June 1995 election which was won by the New National Party under Keith Mitchell, who went on to win the 1999 and 2003 elections, serving for a record 13 years until 2008.[25] Mitchell re-established relations with Cuba and also reformed the country's banking system, which had come under criticism over potential money laundering concerns.[16][25][26]

In 2000–02, much of the controversy of the late 1970s and early 1980s was once again brought into the public consciousness with the opening of the truth and reconciliation commission.[25] The commission was chaired by a Roman Catholic priest, Father Mark Haynes, and was tasked with uncovering injustices arising from the PRA, Bishop's regime, and before. It held a number of hearings around the country. Brother Robert Fanovich, head of Presentation Brothers' College (PBC) in St. George's, tasked some of his senior students with conducting a research project into the era and specifically into the fact that Maurice Bishop's body was never discovered.[65][44]

On 7 September 2004, after being hurricane-free for 49 years, the island was directly hit by Hurricane Ivan.[66] Ivan struck as a Category 3 hurricane, resulting in 39 deaths and damage or destruction to 90% of the island's homes.[16][25][26] On 14 July 2005, Hurricane Emily, a Category 1 hurricane at the time, struck the northern part of the island with 80-knot (150 km/h; 92 mph) winds, killing one person and causing an estimated US$110 million (EC$297 million) worth of damage.[16][26][67] Agriculture, and in particular the nutmeg industry, suffered serious losses, but that event caused changes in crop management and it is hoped that as new nutmeg trees mature, the industry will gradually rebuild. On July 1, 2024, Hurricane Beryl (2024) struck the island of Carriacou, causing widespread damage across all of Grenada and Carriacou. On Carriacou, there was no electricity and limited communication. Throughout the rest of the country, 95% of customers had no power and telecommunications were also damaged.[68]

Mitchell was defeated in the 2008 election by the NDC under Tillman Thomas;[69][70] however, he won the 2013 Grenadian general election by a landslide and the NNP returned to power,[71] winning again by another landslide in 2018.[72] In March 2020, Grenada confirmed its first case of COVID-19 and, as of 17 March 2022[update], 13,921 cases and 217 deaths had been recorded.[73]

On 23 June 2022, the NDC won the general election under Dickon Mitchell, who became prime minister the following day.[74]

Geography

[edit]

The island of Grenada is the southernmost island in the Antilles archipelago, bordering the eastern Caribbean Sea and the western Atlantic Ocean, and roughly 140 km (90 mi) north of both Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago. Its sister islands make up the southern section of the Grenadines, which include Carriacou, Petite Martinique, Ronde Island, Caille Island, Diamond Island, Large Island, Saline Island, and Frigate Island; the remaining islands to the north belong to St Vincent and the Grenadines. Most of the population lives in Grenada, and major towns there include the capital, St. George's, Grenville and Gouyave. The largest settlement on the sister islands is Hillsborough on Carriacou.

Grenada is of volcanic origin,[12] as evident in its soil, mountainous interior, and several explosion craters, including Lake Antoine, Grand Etang Lake, and Levera Pond. Grenada's highest point is Mount St. Catherine, rising to 840 m (2,760 ft) above sea level.[12] Other major mountains include Mount Granby and South East Mountain. Several small rivers with waterfalls flow into the sea from these mountains. The coastline contains several bays, most notably on the southern coast, split into numerous thin peninsulas.

Grenada is home to four ecoregions: Windward Islands moist forests, Leeward Islands dry forests, Windward Islands dry forests, and Windward Islands xeric scrub.[75] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.22/10, ranking it 131st globally out of 172 countries.[76]

Climate

[edit]The climate is tropical: hot and humid in the dry season and cooled by the moderate rainfall in the rainy season. Temperatures range from 22–32 °C (72–90 °F) and are rarely below 18 °C (64 °F).

Grenada lies at the southern edge of the Main Development Region for tropical cyclone activity, though the island has suffered only four landfalling hurricanes in the last several decades.[77] Hurricane Janet passed over Grenada on 23 September 1955, with winds of 185 km/h (115 mph), causing severe damage. The most recent storm to hit Grenada was Hurricane Beryl on 1 July 2024, a strong category 4 hurricane which set the record for the earliest forming Category 5 Hurricane in recorded history and the strongest hurricane to develop within the Main Development Region (MDR) of the Atlantic before the month of July. While all three inhabited Grenadian islands were impacted, it passed directly over the island of Carriacou causing total devastation and the damage and destruction of many vessels (both in water and ashore) in Tyrrel Bay and the Carriacou Mangroves. Petit Martinique also suffered considerable damage with much more limited damage occurring on the main island of Grenada, mainly on the windward and northern portions of the island. Grenada was also impacted by Hurricane Ivan on 7 September 2004,[78] which caused severe damage and thirty-nine deaths, and Hurricane Emily on 14 July 2005, which peaked as a category 5 hurricane on July 16 over the greater Caribbean region. Hurricane Emily caused serious damage in Carriacou and in the north of Grenada, which had been relatively lightly affected by Hurricane Ivan; Grenada has had to be put on Tropical Storm Watch several times since.[77]

It took over five years to officially recover from Ivan, although recovery continued for decades after (e.g., the St. George's Anglican Church and the St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church (Scots Kirk) were restored in 2021).[79]

On July 1, 2024, Hurricane Beryl slammed into Grenada, causing damage throughout the country but especially in Carriacou and Petite Martinique, where the eye of the storm passed.[80] Beryl gained international attention, in part, because of its rapid intensification from a tropical storm to Category 4 hurricane within just a 48 hour period.[81]

Fauna

[edit]Like much of the Caribbean, Grenada is depauperate of large animals. However, native opossums, armadillos, and introduced mona monkeys and mongooses are common. As of June 2024, the avifauna of Grenada included a total of 199 species according to Bird Checklists of the World. Of these, one is endemic (Grenada dove), one has been introduced by humans (Rock Pigeon), and 130 are rare or accidental.[82]

Geology

[edit]Approximately 2 million years ago, in the Pliocene era, the area of what is nowadays Grenada emerged from a shallow sea as a submarine volcano. In recent times, volcanic activity has been non-existent, except for some of its hot spring and underwater volcano Kick 'em Jenny. Most of Grenada's terrain is made up of volcanic activity that took place 1–2 million years ago.[citation needed] There would have been many unknown volcanoes responsible for the formation of Grenada including Grenada's capital St. George's with its horseshoe-shaped harbour, the carenage. Two extinct volcanoes, which are now crater lakes, Grand Etang Lake and Lake Antoine, would have also contributed to the formation of Grenada.

Politics

[edit]Grenada is a constitutional monarchy with Charles III as head of state, represented locally by a governor-general.[12][25] Executive power lies with the head of government, the prime minister. The governor-general role is mainly ceremonial, while the prime minister is usually the leader of the largest party in Parliament.[12]

The Parliament of Grenada consists of a Senate (13 members) and a House of Representatives (15 members). The government and the opposition recommend appoints of senators to the governor-general, while the population elect representatives for five-year terms.[12] Grenada operates a multi-party system, with the largest parties being the centre-right New National Party (NNP) and the centre-left National Democratic Congress (NDC).[12]

In February 2013, the governing National Democratic Congress (NDC) lost the election. The opposition New National Party (NNP) won all 15 seats in the general election. Keith Mitchell, leader of NNP, who had served three terms as prime minister between 1995 and 2008, returned to power.[83] Mitchell subsequently led NNP to win all 15 seats in the House of Representatives again in 2018, marking three separate occasions on which he had achieved this feat.

In November 2021, Prime Minister Keith Mitchell said that the upcoming general elections which were constitutionally due no later than June 2023, was to be the last one for him.[84] Mitchell advised the governor-general on 16 May 2022 to dissolve Parliament a year earlier than the constitutional requirement.[85] The New National Party subsequently lost the 2022 election to the National Democratic Congress, with the NDC winning 9 seats to the NNP’s 6. Dickon Mitchell, a political newcomer who had only taken over as leader of the National Democratic Congress less than a year before the election and never held elected office, was subsequently appointed prime minister.

Foreign relations

[edit]Grenada is a full and participating member of both the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).[12]

The Commonwealth

[edit]Grenada, along with much of the Caribbean region, is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The organisation primarily consists of former British colonies and focuses on fostering international relations between its members.

Organization of American States (OAS)

[edit]Grenada is one of the 35 states which has ratified the OAS charter and is a member of the Organization.[86][87] Grenada entered into the Inter-American system in 1975 according to the OAS's website.[88]

Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty

[edit]On 6 July 1994 at Sherbourne Conference Centre in St. Michael, Barbados, George Brizan signed the Double Taxation Relief (CARICOM) Treaty on behalf of the Government of Grenada.[89] This treaty covered concepts such as taxes, residence, tax jurisdictions, capital gains, business profits, interest, dividends, royalties and other areas.[citation needed]

FATCA

[edit]On 30 June 2014, Grenada formally signed a Model 1 agreement with the United States of America to enable the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA).[90]

ALBA

[edit]In December 2014, Grenada joined Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) as a full member. Prime Minister Mitchell said that the membership was a natural extension of the cooperation Grenada has had over the years with both Cuba and Venezuela.[91]

Military

[edit]Grenada has no standing military, leaving typical military functions to the Royal Grenada Police Force (RGFP) and the Coast Guard of Grenada.[12] The Special Service Unit (SSU) of the RGFP wear combat uniforms and participate in the Regional Security System (RSS), a military defence body of the Eastern Caribbean (who participated in the United States invasion of Grenada in 1983.[92]

In 2019, Grenada signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[93]

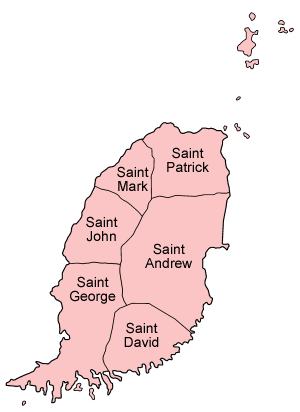

Administrative divisions

[edit]Grenada is divided into six parishes.[12] The area known as Carriacou and Petite Martinique (not pictured) has the status of a dependency.[12]

Human rights

[edit]Homosexuality is illegal in Grenada and punishable by imprisonment.[94]

In 2023, the country scored 89 out of 100 in the Freedom ratings.[95]

Economy

[edit]Grenada has a small economy in which tourism is the major foreign exchange earner.[12] Major short-term concerns are the rising fiscal deficit and the deterioration in the external account balance. Grenada shares a common central bank and a common currency (the East Caribbean dollar) with seven other members of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).[12][96]

Grenada has suffered from a heavy external debt problem, with government debt service payments running at about 25% of total revenues in 2017; Grenada was listed as ninth from bottom in a study of 126 developing countries.[97]

Agriculture and exports

[edit]

Grenada is an exporter of several different spices, most notably nutmeg, its top export and depicted on the national flag, and mace.[98][13] Other major exports include bananas, cocoa, fruit and vegetables, clothing, chocolate and fish.[12]

Nutmeg Industry

[edit]According to a case study released in November 2003,[99] the nutmeg industry in Grenada provided a major source of foreign exchange earnings to the country and acted as a livelihood for a significant portion of the population. The majority of Grenada nutmeg producers are small (e.g. 74.2% of growers have sales volumes of <500 lbs per year, accounting for 21.77% of total production). Only 3.3% of growers have sales over 2500 lbs per year (accounting for 40% of the total output).

At the time the study was released, the majority of the production of nutmeg from within Grenada was derived from four companies:

- Grenada Co-operative Nutmeg Association (GCNA) ;

- West India Spices (formerly W & W Spices, renamed in 2011 following purchase by St Bernard family. Re-sold in 2015 and name maintained);[100]

- Noelville Ltd ;

- De La Grenada Industries.

Tourism

[edit]Tourism is the mainstay of Grenada's economy.[12] Conventional beach and water-sports tourism is largely focused in the southwest region around St George, the airport, and the coastal strip. Ecotourism is growing in significance.[citation needed]

Grenada has many beaches around its coastline, including the 3 km (1.9 mi) long Grand Anse Beach in St. George's, often described as one of the best beaches in the world.[101] Grenada's many waterfalls are also popular with tourists. The nearest to St. George's is the Annandale Waterfalls; others include Mt. Carmel, Concord, Tufton Hall and St Margaret's also known as Seven Sisters.[102]

Several festivals also draw in tourists, such as Grenada's Carnival Spice Mas in August,[103] Carriacou Maroon and String Band Music Festival in April,[104] the Annual Budget Marine Spice Island Billfish Tournament,[105] the Island Water World Sailing Week,[106] and the Grenada Sailing Festival Work Boat Regatta.[107]

Education

[edit]Education in Grenada consists of kindergarten, pre-primary school, primary school, secondary school, and tertiary education. The government spent 10.3% of its budget on education in 2016, the third highest rate in the world.[12] Literacy rates are very high, with 98.6% of the population being able to read and write.[12]

Transport

[edit]Air Travel

[edit]Maurice Bishop International Airport is the country's main airport,[12] connecting the country with other Caribbean islands, the United States, Canada, and Europe. There is also an airport on Carriacou called Lauriston Airport.[25]

Buses

[edit]A semi-organized bus system exists on the island running 9 zones with a total of 44 routes.[108] Buses are privately owned, high-volume (usually 17) passenger vehicles which display a large, circled, zone number sticker on the windshield of the vehicle and generally operate from about 8AM to 8 PM. The cost per person, per segment is $2.50 XCD (Eastern Caribbean Dollar) and is paid to the "conductor", whom usually sits in the first row of main passenger space (so they can open the sliding door) or in the front passenger seat. This conductor can be told where you would like to stop, or a stop can be requested by banging (with a non-ring wearing hand) on the ceiling or wall of the vehicle. It is not uncommon for a passing bus to honk at or for the conductor to yell out the window to a walking person to determine if there is interest in a ride.

Since most buses are privately owned, it is not uncommon for drivers to have installed upgraded sound systems with more than adequate volume.

A separate 3 zone/route system exists on the Grenada island of Carriacou.

Taxis

[edit]Taxis are available through the island, and will display a Taxi sticker in the windshield. Haylup, a Grenada-developed ride-sharing service similar to Uber or Lyft is also an available option for the main tourist areas of the island.

Demographics

[edit]

A majority of Grenadians (82%) are primarily descended from enslaved Africans.[12][25] Few of the indigenous population remained after the successful French colonisation of the island in the 17th century. A small percentage of descendants of indentured workers from India were brought to Grenada between 1857 and 1885, predominantly from the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.[citation needed] Today, Grenadians of Indian descent constitute 2.2% of the population.[12] There is also a small community of French and English descendants.[25] The rest of the population is of mixed descent (13%).[5]

Grenada, like many of the Caribbean islands, is subject to a large amount of out-migration, with a large number of young people seeking more prospects abroad. Popular migration points for Grenadians include more prosperous islands in the Caribbean (such as Barbados), North American cities (such as New York City, Toronto and Montreal), the United Kingdom (in particular, London and Yorkshire;[109] see Grenadians in the UK) and Australia.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Grenada (2011 estimate)[110]

Figures are 2011 estimates[110]

- Protestant 49.2%; includes

- Pentecostal 17.2%

- Seventh Day Adventist 13.2%

- Anglican 8.5%

- Baptist 3.2%

- Church of God 2.4%

- Evangelical 1.9%

- Methodist 1.6%

- Other 1.2%

- Roman Catholic 36%

- none 5.7%

- unspecified 1.3%

- Jehovah's Witness 1.2%

- Rastafari 1.2%

- Other (incl. Hinduism, Islam, Afro-American religions and Judaism) 5.5%

In 2022, Grenada was awarded a score of four out of four for religious freedom by the Freedom House organization.[95]

Languages

[edit]English is the country's official language,[12] but the primary spoken language is either of two creole languages (Grenadian Creole English and, less frequently, Grenadian Creole French) (sometimes called 'patois') which reflects the African, European, and native heritage of the nation. The creoles contain elements from a variety of African languages, French and English.[111] Grenadian Creole French is only spoken in smaller rural areas in the north.[112]

Some Hindustani terms are still spoken amongst the descendants of the Indo-Grenadian community.[citation needed]

The indigenous languages were Iñeri and Karina (Carib).[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]

Island culture is heavily influenced by the African roots of most of the Grenadians, coupled with the country's long experience of colonial rule under the British. Although French influence on Grenadian culture is much less visible than in some other Caribbean islands, surnames and place names in French remain, and the everyday language is laced with French words and the local Creole or Patois.[12] Stronger French influence is found in the well seasoned spicy food and styles of cooking similar to those found in New Orleans, and some French architecture has survived from the 1700s.[citation needed] Indian and Carib Amerindian influence is also seen, especially in the island's cuisine.

Oil down, a stew, is considered the national dish.[113] The name refers to a dish cooked in coconut milk until all the milk is absorbed, leaving a bit of coconut oil in the bottom of the pot. Early recipes call for a mixture of salted pigtail, pig's feet (trotters), salt beef and chicken, dumplings made from flour, and provisions like breadfruit, green banana, yam and potatoes. Callaloo leaves are sometimes used to retain the steam and add extra flavour.[113]

Soca, calypso, kaiso and reggae are popular music genres and are played at Grenada's annual Carnival. Over the years, rap music became popular amongst Grenadian youths, and numerous young rappers have emerged in the island's underground rap scene.[citation needed] Zouk is also being slowly introduced onto the island.[citation needed]

An important aspect of the Grenadian culture is the tradition of storytelling, with folk tales bearing both African and French influences.[citation needed] The character Anancy, a spider who is a trickster, originated in West Africa and is prevalent on other islands as well. French influence can be seen in La Diablesse, a well-dressed she-devil, and Loogaroo (from "loup-garou"), a werewolf.[citation needed]

Media

[edit]Sports

[edit]Olympics

[edit]

Grenada has competed in every Summer Olympics since the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Kirani James won the first Olympic gold medal for Grenada in the men's 400 meters at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, the silver medal in the men's 400 meters at the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro[114] and the bronze medal in the men's 400 meters at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.[115][116] Anderson Peters and Lindon Victor also won bronze medals in the men's javelin throw and decathlon respectively at the 2024 Summer Olympics in France.[117][118]

Cricket

[edit]As with other islands from the Caribbean, cricket is the national and most popular sport and is an intrinsic part of Grenadian culture. The Grenada national cricket team forms a part of the Windward Islands cricket team in regional domestic cricket; however, it plays as a separate entity in minor regional matches,[119] as well as having previously played Twenty20 cricket in the Stanford 20/20.[120]

The Grenada National Cricket Stadium in St. George's hosts domestic and international cricket matches. Devon Smith, record holder for top runs scored in regional first class cricket competitions, was born in the small town of Hermitage.[121][122] T20 World Cup winning allrounder Afy Fletcher was also born and raised in La Fillette, St Andrews.[123][124]

In April 2007, Grenada jointly hosted (along with several other Caribbean states) the 2007 Cricket World Cup. The Island's prime minister was the CARICOM representative on cricket and was instrumental in bringing the World Cup games to the region. After Hurricane Ivan, the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) paid for the new $40 million national stadium and provided the aid of over 300 labourers to build and repair it.[125] During the opening ceremony, the anthem of the Republic of China (ROC, Taiwan) was accidentally played instead of the PRC's anthem, leading to the firing of top officials.[126][127]

Football

[edit]Football is also a very popular sport in Grenada.[128]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ As a Commonwealth realm Grenada retains "God Save the King" as its royal anthem by precedent, with the song played in the presence of members of the royal family. The words King, him and his used at present (in the reign of King Charles III) are replaced by Queen, she and hers when the monarch is female.[3][4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Grenadian Creole English - English Dictionary".

- ^ "Government of Grenada Website". Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "National anthem". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ "King Charles III visits Grenada Parliament, Caribbean Royal Tour 2019" on YouTube

- ^ a b "Grenada - The World Factbook". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "World Religion Database, National Profile".

- ^ "About Grenada, Carriacou & Petite Martinique". Gov.gd. Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook October 2023 (Grenada)". International Monetary Fund. October 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "CIA World Factbook – Grenada". Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Grenada | History, Geography, & Points of Interest". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ a b Hanna, Jonathan A. (2019). "Camáhogne's Chronology: The Radiocarbon Settlement Sequence on Grenada". The Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 55: 101075. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2019.101075. S2CID 198785950.

- ^ a b c d Martin, John Angus (2013). Island Caribs and French Settlers in Grenada: 1498-1763. St George's, Grenada: Grenada National Museum Press. ISBN 9781490472003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Steele 2003, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Jacobs, Curtis (1 January 2015), "Grenada, 1949–1979: Precursor to Revolution", The Grenada Revolution, University Press of Mississippi, doi:10.14325/mississippi/9781628461510.003.0002, ISBN 978-1-62846-151-0

- ^ a b Crask, Paul (2009). Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 5. ISBN 9781841622743.

- ^ a b Crask, Paul (2009). Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 6. ISBN 9781841622743.

- ^ Crask, Paul (2009). Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 9781841622743.

- ^ Higman, B. W. (2021). A Concise History of the Caribbean. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-108-48098-7.

- ^ Siegel, Peter E.; Jones, John G.; Pearsall, Deborah M.; et al. (2015). "Paleoenvironmental Evidence for First Human Colonization of the Eastern Caribbean". Quaternary Science Reviews. 129: 275–295. Bibcode:2015QSRv..129..275S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.10.014.

- ^ Whitehead, Neil (1995). Wolves from the Sea: Readings in the Anthropology of the Native Caribbean. Leiden: KITLV Press.

- ^ Hanna, Jonathan A. (2018). "Grenada and the Guianas: Demography, Resilience, and Terra Firme during the Caribbean Late Ceramic Age". World Archaeology. 50 (4): 651–675. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1607544. S2CID 182630336.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Encyclopedia Britannica – Grenada". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "About Grenada: Historical Events". Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Crouse, Nellis Maynard (1940). French pioneers in the West Indies, 1624–1664. New York: Columbia university press. p. 196.

- ^ Steele 2003, pp. 39–48.

- ^ Steele 2003, pp. 35–44.

- ^ Bair, Diane; Wright, Pamela (10 December 2019). "Chocolate overload? On Grenada, it's entirely possible". bostonglobe.com. Boston Globe.

- ^ Steele 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Jacobs, Curtis. "The Fédons of Grenada, 1763–1814". University of the West Indies. Archived from the original on 31 August 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Cox, Edward L. (1982). "Fedon's Rebellion 1795–96: Causes and Consequences". The Journal of Negro History. 67 (1): 7–19. doi:10.2307/2717757. JSTOR 2717757. S2CID 149940460.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Britannica – Anguilla". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "Grenada Nutmeg – GCNA – Organic Nutmeg Producers, Nutmeg Oil – Nutmeg trees – Nutmeg farming in Grenada". Travelgrenada.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Marryshow". University of West Indies. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "From Old Representative System to Crown Colony". Bigdrumnation.org. 1 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Year Book of the Bermudas, the Bahamas, British Guiana, British Honduras and the British West Indies. Vol. 17. T. Skinner. 1944. p. 32.

- ^ "Eric Gairy - Caribbean Hall of Fame". caribbean.halloffame.tripod.com.

- ^ a b "1951 and Coming of General Elections". BigDrumNation. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Nohlen, D (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I, p301-302 ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ "Grenada : History". Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "The end of Eric Gairy". March 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ a b LA Times website, Search for Body Yields Lessons for Students, by Mark Fineman, dated September 2, 2000

- ^ Kukielski, Philip (2019). The U.S. Invasion of Grenada : legacy of a flawed victory. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 183–84. ISBN 978-1-4766-7879-5. OCLC 1123182247.

- ^ Anthony Payne, Paul Sutton, and Tony Thorndike (1984). "Grenada: Revolution and Invasion". Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709920809. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hudson Austin (1983). ""Hudson Austin Speech announcing the killing of Maurice Bishop October 19, 1983"". minute 4:37 of 6:05. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Gailey, Phil; Warren Weaver Jr. (26 March 1983). "Grenada". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ Julie Wolf (1999–2000). "The Invasion of Grenada". PBS: The American Experience (Reagan). Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ^ Cole, Ronald (1997). "Operation Urgent Fury: The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ Autobiography: Sir Paul Scoon 'Survival for Service'. Macmillan Caribbean. 2003. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Sir Paul Scoon, G-G of Grenada, at 2:36 on YouTube

- ^ Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: At her Zenith (2016) p. 130.

- ^ "United Nations General Assembly resolution 38/7". United Nations. 2 November 1983. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Assembly calls for cessation of 'armed intervention' in Grenada". UN Chronicle. 1984. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007.

- ^ Richard Bernstein (29 October 1983). "U.S. VETOES U.N. RESOLUTION 'DEPLORING' GRENADA INVASION". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Amnesty International (October 2003). "The Grenada 17: the last of the cold war prisoners?" (PDF).

- ^ Cody, Edward (24 December 1983). "Grenada's Vacuum Tempts Ex-Leader". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Political Parties of the World (6th edition, 2005), ed. Bogdan Szajkowski, page 265.

- ^ "Jan 1985 – General election and resumption of Parliament – Formation of Blaize government – Foreign relations Opening of airport – Start of murder trial", Keesing's Record of World Events, volume 31, January 1985, Grenada, page 33,327.

- ^ "Grenada profile". BBC News. 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Biography: Ben Jones". Gov.gd. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Former Grenadian PM Nicholas Brathwaite dies". Jamaica Observer. 29 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Feb 1995 – New Prime Minister – Government changes", Keesing's Record of World Events, Volume 41, February 1995 Grenada, Page 40402.

- ^ See Maurice Paterson's book, published before this event, called Big Sky Little Bullet

- ^ Green, Eric (24 February 2005). "Grenada Making Comeback from Hurricane Ivan". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 22 November 2006. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ James L. Franklin & Daniel P. Brown (10 March 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Emily" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. NOAA. Retrieved 13 March 2006.

- ^ Gilbert, Mary; Wolfe, Elizabeth (1 July 2024). "Hurricane Beryl devastates Grenada: 'In half an hour, Carriacou was flattened'". CNN. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "New Grenada prime minister vows to boost economy, lower cost of living". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 9 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ George Worme (10 July 2008). "Thomas wins by a landslide in Grenada". The Nation. Barbados. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008.

- ^ "Clean sweep" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Jamaica Observer, 21 February 2013.

- ^ "Clean sweep! Grenada PM predicts repeat victory". WIC News. 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Reported Cases and Deaths by Country, Territory, or Conveyance". Worldometer. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Live blog: Grenada votes election 2022 | Loop Caribbean News". Loop News. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Dinerstein E, Olson D, Joshi A, Vynne C, et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham HS, Duncan A, Evans TD, Jones KR, et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ a b Grenada Weather website, Tropical Storms and Hurricanes, retrieved 2023-12-19

- ^ Guardian Newspaper website, Hurricane Ivan Devastates Grenada, article dated September 9, 2004

- ^ Reliefweb (2009), Grenada: Dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Ivan - Grenada, retrieved 20 October 2024

- ^ Cappucci, Matthew (1 July 2024). "Caribbean island of Carriacou 'flattened' after Hurricane Beryl makes landfall". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Andrea (1 July 2024). "Hurricane Beryl's Unprecedented Intensification Is an "Omen" for the Rest of the Season". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 1 July 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Grenada bird checklist - Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World". avibase.bsc-eoc.org. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Grenada opposition wins clean sweep in general election". BBC News. 20 February 2013.

- ^ "PM Mitchell: Upcoming general elections will be fascinating | NOW Grenada". 2 November 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ "UPDATE: Election bell rung, PM Mitchell going after historic 6th term". Loop. 15 May 2022. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "Member States". OAS. August 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "SLA :: Department of International Law (DIL) :: Inter-American Treaties". OAS. August 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Member State :: Grenada". OAS. August 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "The double taxation relief (Caricom) order, 1994" (PDF).

- ^ "Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA)". Treasury.gov. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Grenada Joins ALBA". Now Grenada. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ RGFP (2023), Special Services Unit (SSU), retrieved 6 October 2023

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ "State-Sponsored Homophobia 2019" (PDF). International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association. December 2019.

- ^ a b Freedom House, "Grenada: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report", retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to the OECS". Oecs.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Elliott, Larry (18 March 2018). "Developing countries at risk from US rate rise, debt charity warns". Retrieved 19 March 2018. Jubilee Debt Campaign study

- ^ "Nutmeg, mace and cardamons (HS: 0908) Product Trade, Exporters and Importers". oec.world. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Singh, Ranjit H. "THE NUTMEG AND SPICE INDUSTRY IN GRENADA: INNOVATIONS AND COMPETITIVENESS - A Case Study". ResearchGate: 7, 10, 12, 25. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ Collins, L Simeon (19 February 2024). "Agro-processing in Grenada and its future". nowgrenada. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "The 10 Best Beaches in the World". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013.

- ^ Cruisemanic (14 June 2021). "Top 10 Things to Do in Grenada". Cruise Panorama.

- ^ "Spicemas Corporation". Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "11th Carriacou Maroon & String Band Music Festival | Events | Plan Your Vacation". www.grenadagrenadines.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "51st Annual Budget Marine Spice Island Billfish Tournament | Events | Plan Your Vacation". www.grenadagrenadines.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "Event Schedule". Grenada Sailing Week. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ "Grenada, secret gem of Caribbean, a must-see sailing destination". pressmare.it. Seahorse Magazine. 17 September 2021.

- ^ Grenada. "Transport system". Public Transport Plan for Grenada. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Yorkshire's Windrush generation to share their stories in new film". Yorkshire Post. 12 September 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Central America and Caribbean :: GRENADA". CIA The World Factbook. 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Featuring the Caribbean: Grenada's plan to make quality training accessible to all". unesco.org. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. 10 March 2017.

- ^ University of the West Indies website Are They Dying? The Case of Some French-lexifier Creoles, by Jo-Anne Ferreira and David Holbrook (2001), page 9]

- ^ a b "Oil down – National Dish of Grenada". Gov.gd. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ "Ambassador Kirani James brings home Olympic silver medal for Grenada | One Young World". www.oneyoungworld.com. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "Kirani JAMES". Olympics.com. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ "GRENADA LOVES 400M". World Athletics. 9 August 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ DeShong, Dillon (8 August 2024). "Grenada's Anderson Peters takes bronze in men's javelin at Paris 2024". Loop News. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Hoopes, Tom (6 August 2024). "Always a Raven: Medalist's Journey From Kansas College to Paris Olympics". Benedictine College Media & Culture. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "Other Matches played by Grenada". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Twenty20 Matches played by Grenada". CricketArchive. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "PAVILION NAMED IN HONOUR OF DEVON SMITH". Windies Cricket. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ McDonald, Michelle L. (20 April 2015). "Devon Smith On Verge Of Creating History In Grenada". Cricket Interviews. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Corion, Kimron (31 January 2017). "Afy Fletcher". I Am Grenadian. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "Female Cricketer Afy Fletcher recognised as a sports icon | NOW Grenada". 11 November 2024. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "Grenada: Bandleader Loses Job in Chinese Anthem Gaffe". The New York Times. Associated Press. 8 February 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Grenada Goofs: Anthem Mix Up". BBCCaribbean.com. 5 February 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Scott Conroy (3 February 2007). "Taiwan Anthem Played For China Officials". CBS News. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Famous Soccer Players from Grenada". Ranker. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Adkin, Mark. 1989. Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada: The Truth Behind the Largest US Military Operation Since Vietnam. Trans-Atlantic Publications. ISBN 0-85052-023-1

- Beck, Robert J. 1993. The Grenada Invasion: Politics, Law, and Foreign Policy Decisionmaking. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8709-4

- Brizan, George 1984. Grenada Island of Conflict: From Amerindians to People's Revolution 1498–1979. London, Zed Books Ltd., publisher; Copyright, George Brizan, 1984.

- Martin, John Angus. 2007. A–Z of Grenada Heritage. Macmillan Caribbean.

- "Grenada Heritage". Grenadaheritage.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Sinclair, Norma. 2003. Grenada: Isle of Spice (Caribbean Guides). Interlink Publishing Group; 3rd edition. ISBN 0-333-96806-9

- Stark, James H. 1897. Stark's Guide-Book and History of Trinidad including Tobago, Grenada, and St. Vincent; also a trip up the Orinoco and a description of the great Venezuelan Pitch Lake. Boston, James H. Stark, publisher; London, Sampson Low, Marston & Company.

- Steele, Beverley A. (2003). Grenada: A History of Its People (Island Histories). Oxford: MacMillan Caribbean. ISBN 978-0-333-93053-3.

External links

[edit] Wikimedia Atlas of Grenada

Wikimedia Atlas of Grenada- Official Website of the Government of Grenada

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. p. 184.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 578.

- Grenada. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Grenada at UCB Libraries GovPubs.

- Grenada from the BBC News.

- Presentation Brothers College

- Key Development Forecasts for Grenada from International Futures.

- The Grenada Newsletter (1974–1994) in the Digital Library of the Caribbean

- The dream of a Black utopia, podcast from The Washington Post – includes interview with Dessima Williams, Grenada's former ambassador to the U.S.

- Grenada

- 1640s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1649 establishments in North America

- 1649 establishments in the French colonial empire

- 1760s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1763 establishments in North America

- 1763 establishments in the British Empire

- 1970s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1974 establishments in North America

- Countries and territories where English is an official language

- Countries in North America

- Countries in the Caribbean

- Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas

- Former French colonies

- Island countries

- Member states of the Caribbean Community

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

- Member states of the United Nations

- Small Island Developing States

- States and territories established in 1974

- Volcanic islands

- Windward Islands