Spherical aberration

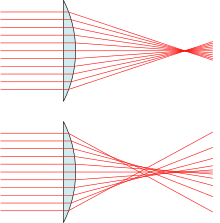

The bottom example depicts a real lens with spherical surfaces, which produces spherical aberration: The different rays do not meet after the lens in one focal point. The further the rays are from the optical axis, the closer to the lens they intersect the optical axis (positive spherical aberration).

(Drawing is exaggerated.)

In optics, spherical aberration (SA) is a type of aberration found in optical systems that have elements with spherical surfaces. This phenomenon commonly affects lenses and curved mirrors, as these components are often shaped in a spherical manner for ease of manufacturing. Light rays that strike a spherical surface off-centre are refracted or reflected more or less than those that strike close to the centre. This deviation reduces the quality of images produced by optical systems. The effect of spherical aberration was first identified in the 11th century by Ibn al-Haytham who discussed it in his work Kitāb al-Manāẓir.[1]

Overview

[edit]A spherical lens has an aplanatic point (i.e., no spherical aberration) only at a lateral distance from the optical axis that equals the radius of the spherical surface divided by the index of refraction of the lens material.

Spherical aberration makes the focus of telescopes and other instruments less than ideal. This is an important effect, because spherical shapes are much easier to produce than aspherical ones. In many cases, it is cheaper to use multiple spherical elements to compensate for spherical aberration than it is to use a single aspheric lens.

"Positive" spherical aberration means rays near the outer edge of a lens are bent more than would be predicted for an ideal lens. "Negative" spherical aberration means such rays are bent less than would be predicted.

The effect is proportional to the fourth power of the diameter and inversely proportional to the third power of the focal length, so it is much more pronounced at short focal ratios, i.e., "fast" lenses.

Correction

[edit]In lens systems, aberrations can be minimized using combinations of convex and concave lenses, or by using aspheric lenses or aplanatic lenses.

Lens systems with aberration correction are usually designed by numerical ray tracing. For simple designs, one can sometimes analytically calculate parameters that minimize spherical aberration. For example, in a design consisting of a single lens with spherical surfaces and a given object distance o, image distance i, and refractive index n, one can minimize spherical aberration by adjusting the radii of curvature and of the front and back surfaces of the lens such that

- , where the signs of the radii follow the Cartesian sign convention.

For small telescopes using spherical mirrors with focal ratios shorter than f/10, light from a distant point source (such as a star) is not all focused at the same point. Particularly, light striking the inner part of the mirror focuses farther from the mirror than light striking the outer part. As a result, the image cannot be focused as sharply as if the aberration were not present. Because of spherical aberration, telescopes with focal ratio less than f/10 are usually made with non-spherical mirrors or with correcting lenses.

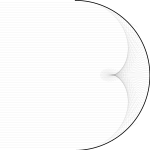

Spherical aberration can be eliminated by making lenses with an aspheric surface. Descartes showed that lenses whose surfaces are well-chosen Cartesian ovals (revolved around the central symmetry axis) can perfectly image light from a point on the axis or from infinity in the direction of the axis. Such a design yields completely aberration-free focusing of light from a distant source.[2]

In 2018, Rafael G. González-Acuña and Héctor A. Chaparro-Romo, graduate students at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education in Mexico, found a closed formula for a lens surface that eliminates spherical aberration.[3][4][5] Their equation can be applied to specify a shape for one surface of a lens, where the other surface has any given shape.

Estimation of the aberrated spot diameter

[edit]Many ways to estimate the diameter of the focused spot due to spherical aberration are based on ray optics. Ray optics, however, does not consider that light is an electromagnetic wave. Therefore, the results can be wrong due to interference effects arisen from the wave nature of light.

Coddington notation

[edit]A rather simple formalism based on ray optics, which holds for thin lenses only, is the Coddington notation.[6] In the following, n is the lens' refractive index, o is the object distance, i is the image distance, h is the distance from the optical axis at which the outermost ray enters the lens, is the first lens radius, is the second lens radius, and f is the lens' focal length. The distance h can be understood as half of the clear aperture.

By using the Coddington factors for shape, s, and position, p,

one can write the longitudinal spherical aberration as [6]

If the focal length f is very much larger than the longitudinal spherical aberration LSA, then the transverse spherical aberration, TSA, which corresponds to the diameter of the focal spot, is given by

See also

[edit]- Achromatic lens

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Maksutov telescope

- Parabolic reflector

- Ritchey–Chrétien telescope

- Schmidt corrector plate

- Soft focus

References

[edit]- ^ Boudrioua, Azzedine; Rashed, Roshdi; Lakshminarayanan, Vasudevan (2017-08-15). Light-Based Science: Technology and Sustainable Development, The Legacy of Ibn al-Haytham. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-351-65112-7.

- ^ Villarino, Mark B (2007). "Descartes' perfect lens". arXiv:0704.1059 [math.GM].

- ^ Machuca, Eduardo (July 5, 2019). "Goodbye Aberration: Physicist Solves 2,000-Year-Old Optical Problem". PetaPixel. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^ González-Acuña, Rafael G.; Chaparro-Romo, Héctor A. (2018). "General formula for bi-aspheric singlet lens design free of spherical aberration". Applied Optics. 57 (31): 9341–9345. arXiv:1811.03792. Bibcode:2018ApOpt..57.9341G. doi:10.1364/AO.57.009341. PMID 30461981. S2CID 53695913.

- ^ Liszewski, Andrew (August 7, 2019). "A Mexican Physicist Solved a 2,000-Year Old Problem That Will Lead to Cheaper, Sharper Lenses". Gizmodo. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Smith, T. T. (1922). "Spherical Aberration in thin lenses". Scientific Papers of the Bureau of Standards. 18: 559–584. doi:10.6028/nbsscipaper.127.

External links

[edit]- Spherical aberration Archived 2012-07-23 at the Wayback Machine at vanwalree.com, PA van Walree, viewed 28 January 2007.

- http://www.telescope-optics.net/spherical1.htm

- Non-English articles on the Acuña-Romo equation: Spanish, German, Italian, Russian

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}s&={\frac {R_{2}+R_{1}}{R_{2}-R_{1}}}\\[8pt]p&={\frac {i-o}{i+o}},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/153e0891f9c02c41916455af75e53445456ccee3)