Species (film)

| Species | |

|---|---|

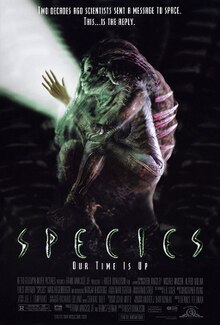

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roger Donaldson |

| Written by | Dennis Feldman |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Andrzej Bartkowiak |

| Edited by | Conrad Buff |

| Music by | Christopher Young |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | MGM/UA Distribution Co.[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million[3] |

| Box office | $113.3 million[3] |

Species is a 1995 American science fiction horror film directed by Roger Donaldson and written by Dennis Feldman. It stars Ben Kingsley, Michael Madsen, Alfred Molina, Forest Whitaker, Marg Helgenberger, and Natasha Henstridge in her film debut role. The film's plot concerns a motley crew of scientists and government agents who try to track down Sil (Henstridge), a seductive extraterrestrial-human hybrid, before she successfully mates with a human male.

The film was conceived by Feldman in 1987, and was originally pitched as a film treatment in the style of a police procedural, entitled The Message. When The Message failed to attract the studios, Feldman re-wrote it as a spec script, which ultimately led to the making of the film. The extraterrestrial aspect of Sil's character was created by H. R. Giger, who was also responsible for the beings from the Alien franchise. The effects combined practical models designed by Giger collaborator Steve Johnson and XFX, with computer-generated imagery done by Richard Edlund's Boss Film Studios. Giger felt that the film and the character were too similar to Alien, so he pushed for script changes.

Most of the principal photography was done in Los Angeles, California, where the film is set. Several scenes were filmed in Utah and at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Species was met with mixed reviews from critics, who felt that the film's execution did not match the ambition of its premise, but nevertheless was a box office success, partly due to the hype surrounding Henstridge's nude scenes in various tabloid newspapers and lad mags of the time, grossing US$113.3 million ($227 million in 2023 dollars). It spawned a franchise, which includes one theatrical sequel (Species II), as well as two direct-to-television sequels (Species III and Species – The Awakening). Species was adapted into a novel by Yvonne Navarro and two comic book series by Dark Horse Comics, one of which was written by Feldman. The film may have also influenced the legend of the chupacabra. The film was mentioned by Podcast "The Red Thread" in reference to this relation to the chupacabra.

Plot

[edit]During the SETI program, Earth's scientists send out transmissions, such as the Arecibo message, with information about Earth and its inhabitants in the hopes of finding life beyond Earth. After receiving transmissions from an alien source on how to create limitless fuel and an alien DNA sample with instructions on how to splice it with that of humans, the scientists assume the aliens are friendly. Inspired by the second transmission, a government team led by Xavier Fitch commissions a genetic experiment meant to create a female alien/human hybrid organism under the belief that she would have "more docile and controllable" traits. They eventually produce a girl codenamed "Sil", who initially resembles a normal human and develops into a 12-year-old in three months.

Due to her violent outbursts while she is sleeping, the scientists deem her dangerous and prepare to kill her using cyanide gas, but she breaks out of her containment cell and escapes. Fearing she will mate with human males and produce offspring that will eventually exterminate the human race, the government assembles a team consisting of anthropologist Dr. Stephen Arden, molecular biologist Dr. Laura Baker, "empath" Dan Smithson, and black ops mercenary Preston "Press" Lennox to track and kill Sil. Using her superhuman strength and intelligence and regenerative capability to evade capture, Sil matures rapidly into her early twenties and travels to Los Angeles, where she kills several people to prevent them from alerting authorities and disguises herself.

After failing to mate with and killing Robbie, a diabetic young man, and John Carey, a man she met following a car accident, Press and Baker find Sil. She assumes her alien form and flees into a nearby forest, where she kidnaps a woman to assume her identity. Secretly returning to Carey's home to spy on Fitch, Sil reads his lips and determines he and his team plan to stake out a nightclub to find her. After being spotted by Smithson, Sil lure her pursuers into a car chase wherein she leaves the woman she kidnapped to die while crashing the car into a high-voltage transformer and jumping out at the last minute. She later cuts and dyes her hair before developing an attraction towards Press, whom she dreamed of the previous night. Meanwhile, the government team celebrate Sil's apparent death at a hotel, where Sil stealthily stalks them. Arden, upset about being alone, goes to his room to find Sil waiting for him. They soon have sex, resulting in her instantly becoming pregnant before she kills him once he realizes who she is. Sensing her presence, Smithson alerts the remaining team members. Sil transforms once more and escapes into the sewers. The team pursue, but Sil kills Fitch before giving birth. Her offspring subsequently attacks Smithson, who incinerates it with a flamethrower while Press kills Sil with a grenade launcher. As the survivors leave, they fail to notice a rat gnawing on one of Sil's severed tentacles before mutating and killing another rat.

Cast

[edit]- Natasha Henstridge as Sil

- Michelle Williams as Young Sil

- Dana Hee as Alien Sil

- Frank Welker as Alien Sil (voice)

- Ben Kingsley as Xavier Fitch

- Michael Madsen as Preston "Press" Lennox

- Alfred Molina as Dr. Stephen Arden

- Forest Whitaker as Dan Smithson

- Marg Helgenberger as Dr. Laura Baker

- Whip Hubley as John Carey

- Anthony Guidera as Robbie

- Matthew Ashford as Man In Club

- Kurtis Burow as Baby Boy, Sil's Offspring

Influence and themes

[edit]Since Sil grows rapidly and kills humans with ease, at a certain point film character Dr. Laura Baker speculates if she was a biological weapon sent by a species who thought humans were like an intergalactic weed. Feldman declared that he wanted to explore this theme further in the script, as it discussed mankind's place in the universe and how other civilizations would perceive and relate to humanity, considering that "maybe [humans are] not a potential threat, maybe a competitor, maybe a resource".[4] He also declared that more could be said about Sil's existentialist doubts, as she does not know her origin or purpose, and only follows her instinct to mate and perpetuate the species.[4]

Writing for the Journal of Popular Film & Television, Susan George authored a paper that dealt with the portrayal of procreation in Species, Gattaca and Mimic. George compares the character of Fitch to "an updated Dr. Frankenstein",[5] and explores the development of Sil's maternal aspirations, which convert the character into an "archaic mother" figure similar to the xenomorph creature in the Alien series, both of which are, she claims, portrayed negatively.[5] George further states that a recurring theme in science fiction films is a response to "this kind of powerful female sexuality and 'alien-ness'" in that "the feminine monster must die as Sil does at the end of Species".[5] Feldman himself considered that an underlying theme regarded "a female arriving and seeking to find a superior mate".[4]

A five-year investigation into accounts of the chupacabra, a well known cryptid, revealed that the original sighting report of the creature in Puerto Rico by Madeline Tolentino may have been inspired by the character Sil. This was detailed in paranormal investigator and skeptic Benjamin Radford's book Tracking the Chupacabra.[6] According to Virginia Fugarino of Memorial University of Newfoundland writing for the Journal of Folklore Research, Radford found a link between the original eyewitness report and the design of Sil in her alien form, and hypothesized that "[Species], which [Tolentino] did see before her sighting, influenced what she believes she saw of the chupacabra".[7]

Production

[edit]

Writing and development

[edit]Dennis Feldman had the idea for Species in 1987, as he worked on another film about an alien invasion,[8] Real Men.[4] Having read an article by Arthur C. Clarke about the insurmountable odds against an extraterrestrial craft ever locating and visiting Earth, given that stellar distances are great, and faster-than-light travel is unlikely, Feldman started to think that it was "unsophisticated for any alien culture to come here in what [he]'d describe as a big tin can".[9] Thus in turn he considered that the possibility of extraterrestrial contact was through information.[4] Then he detailed that a message would contain instructions from across the void to build something that would talk to men. Instead of a mechanical device, Feldman imagined wetware. The visitor would adapt to Earth's environment through DNA belonging to Earth's organisms.[9] Mankind has sent to space transmissions "giving out directions" such as the Arecibo message, which Feldman considered unwary, as they relay information to potential predators from outer space. He pointed out that "in nature, one species would not want a predator to know where it hides".[10]

Therefrom emerged a film treatment called The Message.[4] The original script had more of a police procedural approach, with the alien being created by a "bathtub geneticist"[9] who had just had his project aborted by the government, and a biologist who had worked on the project getting along with a police officer to search for the creature. Eventually Feldman came to believe this concept had some credibility issues, and instead changed the protagonists to a government team. After coining the name "Sil", Feldman initially thought of forming an acronym, but in the end chose only the three-letter name after learning about the codons of the genetic code, which can be represented in groups of three letters. Sil would originally emerge from a DNA sequence manipulating human DNA, and constantly mutate as she used the human junk DNA to access "all the defenses of the entire animal kingdom that [humans] evolved through – including ones that had never developed, plus ones [Earth's scientists] don't know about that have become extinct".[9] Among the research Feldman did for the script included going to sessions of UCLA's Center for the Study of Evolution and the Origin of Life (CSEOL), talking to SETI scientists, and visiting the Salk Institute for Biological Studies to talk with researchers working on the Human Genome Project.[4] The Message was offered to several studios, but was passed up.[11]

In 1993, Feldman reworked his ideas into a spec script.[11] This was sent to producer Frank Mancuso, Jr., who had hired Feldman to adapt Sidney Kirkpatrick's A Cast of Killers.[8] The producer got attracted to the creative possibilities as the film offered "the challenge of walking that fine line between believability and pushing something as far as it can go".[10] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer got interested on the project, and while Feldman had some initial disagreements on the budget, after considering other studios he signed with MGM.[9] In turn, the now retitled Species attracted director Roger Donaldson, who was attracted to its blend of science fiction and thriller. The script underwent eight different drafts, written over an eight-month period, before Donaldson was content that flaws in the story's logic had been corrected. At one point another writer, Larry Gross, tried his hand with the script, but ultimately all the work was done by Feldman.[8] Feldman would remain as a co-producer. While the initial Species script suggested a love triangle between Sil and two government team members, the dissatisfaction of the crew eventually led to changes to the ending, which ended up featuring Sil having a baby that would immediately prove dangerous.[4]

When Donaldson was announced as the director in 1994, Mancuso stated that most of the $35 million budget would be spent on effects, as "it's not a movie that calls for stars. We're going to try and put as much money as we can below the line and allow the effects and the creature to be the highlights of the film".[12] The lesser emphasis on actors included a newcomer, former model Natasha Henstridge, as the human version of the creature Sil.[13]

Design

[edit]

Sil was designed by Swiss artist H. R. Giger, who also created the creatures in the Alien films. Donaldson thought Giger was the best man for the film after reading his compendium Necronomicon, and eventually he and Mancuso flew to Switzerland to meet the artist. What attracted Giger was the opportunity to design "a monster in another way—an aesthetic warrior, also sensual and deadly, like the women look in [his] paintings".[8] While Giger opted to stay in Switzerland to take care of his dying mother instead of flying to Los Angeles to accompany production, he built some puppets in his own studio, and later faxed sketches and airbrush paintings as production went through.[8]

The practical models were made by Steve Johnson and his company XFX, which had already worked with Giger's designs in Poltergeist II: The Other Side. Giger had envisioned more stages of Sil's transformation, but the film only employed the last one, where she is "transparent outside and black inside—like a glass body but with carbon inside",[14] with XFX doing the translucent skin based on what they had done for the aliens of The Abyss. Sil's alien form had both full-body animatronics with replaceable arms, heads and torsos, and a body suit.[14] Richard Edlund's Boss Film Studios was hired for over 50 shots of computer-generated imagery, which included one of the earliest forms of motion capture effects. Using a two-foot-high (60 cm) electric puppet that had sensors translating its movements to a digital Sil, Boss Films managed to achieve in one day what would have once taken as much as three weeks with practical effects.[10]

Giger was unhappy with some elements he found to bear similarity with other films, particularly the Alien franchise. At one point he sent a fax to Mancuso finding five similarities: a "chestburster" (as Sil giving birth echoed the infant Alien breaking out of its host's chest), the creature having a punching tongue (Giger at first wanted Sil's tongue to be composed of barbed hooks), a cocoon, the use of flame throwers, and having Giger as the creature designer. A great point of contention was the ending, which Giger considered derivative from the climaxes from both Alien 3 and Terminator 2: Judgment Day. The designer felt that horror films frequently held some final confrontation with fire, which he considered old-fashioned and linked to medieval witch trials. He sent some ideas for the climax to the producers, with them accepting to have Sil's ultimate death occurring by headshot.[8]

Filming

[edit]Filming happened mostly in Los Angeles, including location shooting at Sunset Strip, Silver Lake, Pacific Palisades, the Hollywood Hills and the Biltmore Hotel. Id Club, the nightclub featured in the film, was built within Hollywood's Pantages Theater, while the hills above Dodger Stadium near Elysian Park were used for the car chase and crash where Sil fakes her death. For the opening scenes in Utah, the Tooele Army Depot dubbed as the outside of the research facility—the interiors were shot at the Rockwell International Corporation laboratory in California—and a Victorian-era train station in Brigham City was part of Sil's escape. Other locations included the Santa Monica Pier and the Arecibo Telescope in Puerto Rico. The most complex sets involved the sewer complex and a tar-filled granite cavern where the ending occurs. Donaldson wanted a maze quality for the sewers, which had traces of realism (such as tree roots breaking through from the ceiling) and artistic licenses. Production designer John Muto intentionally designed the sewers wider and taller than real ones, as well as with walkways, but nevertheless aiming for a claustrophobic and realistic atmosphere. The tunnels were built out of structural steel, metal rod, plaster and concrete to endure the fire effects, and had its design based on the La Brea Tar Pits, with Muto describing them as "just the sort of place in which a creature from another planet might feel at home".[15]

Release

[edit]Species received a wide theatrical release on July 7, 1995. Its opening weekend was $17.1 million, MGM's biggest opening at the time and ranked second in the box office ranking behind Apollo 13.[16] Budgeted at $35 million, the film earned a total of $113 million worldwide ($227 million adjusted for inflation), including $60 million in the United States.[3] Audiences polled by CinemaScore during opening weekend gave the film an average grade of "B−" on a scale ranging from A+ to F.[17]

MGM Home Entertainment released the film on DVD in March 1997, which contains a booklet with trivia and production notes,[18] and on VHS in August 1999.[3][19] In July 2006, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment released it on Blu-ray, whose supplements includes several featurettes as well as two audio commentary tracks: one by director Roger Donaldson, Natasha Henstridge and Michael Madsen, and another from Donaldson, cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak, make-up effects creator Steve Johnson, visual effects supervisor Richard Edlund and producer Frank Mancuso Jr.[20] In July 2017, Scream Factory released a collector's edition Blu-ray, issued with a concoction of new and archival bonus contents which have been ported over from original DVD and Blu-ray versions.[21]

Reception

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 42% based on 73 reviews, with an average rating of 5.30/10 and a critical consensus which reads: "Species shows flashes of the potential to blend exploitation and sci-fi horror in ingenious ways, but is ultimately mainly interested in flashing star Natasha Henstridge's skin".[22] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 49 out of 100 based on 25 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[23]

Roger Ebert gave it 2 out of 4 stars, criticizing the film's plot and overall lack of intelligence.[24] Cristine James from Boxoffice magazine gave the film 2 out of 5 stars, describing it as "Alien meets V meets Splash meets Playboy's Erotic Fantasies: Forbidden Liaisons, diluted into a diffuse, misdirected bore".[25] James Berardinelli gave the film 2½ out of 4 stars, stating that "as long as you don't stop to think about what's going on, Species is capable of offering its share of cheap thrills, with a laugh or two thrown in as well".[26] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly found the film lacking in imagination and special effects, also commenting that Alfred Molina "sport[s] a haircut that's scarier than the creature".[27] Variety's review of the film described it as a "gripping if not overly original account of an extraterrestrial species attempting to overwhelm our own" and that Ben Kingsley and other lead actors "have only two-dimensional roles to engage them". The review notes the similarity between H.R. Giger's design of Sil and his work on Alien.[28]

Scott Weinberg of DVD Talk praised the acting, Feldman's screenplay and Donaldson's direction. He concluded by saying that Species makes for "a very good time for the genre fans".[29] Mick LaSalle, writing for San Francisco Chronicle, was notedly less enthusiastic, quipping that if "Species were a little bit worse, it would have a shot at becoming a camp classic".[30] Los Angeles Times critic Peter Rainer described Species as "a pretty good Boo! movie", finding it an entertaining thriller while unoriginal and with ineffective tonal shifts.[31]

Related works

[edit]Adaptations

[edit]Yvonne Navarro co-wrote a novelization based on the original screenplay with Dennis Feldman. The book gives several in-depth details about the characters not seen in the film, such as Sil's ability to visualize odors and determine harmful substances from edible items by the color. Gas appears black, food appears pink, and an unhealthy potential mate appears to give off green fumes. Other character details include Preston's background in tracking down AWOL soldiers as well as the process of decoding the alien signal. Although no clues are given as to its origin, it is mentioned that the message was somehow routed through several black holes to mask its point of origin.[32] An audiobook version narrated by Alfred Molina won the Audie Award for Solo Performance.[33]

Dark Horse Comics published a four-issue comic book adapting the film, written by Feldman and penciled by Jon Foster. Dark Horse would also publish a mini-series with an all-new storyline,[9] Species: Human Race, released in 1997.[34] West End Games released a World of Species sourcebook for its Masterbook role-playing game system.[35] MGM had partnered with Cyberdreams to make a computer game based on the film, and while the company managed to release an H.R. Giger screen saver featuring Species images, the game never came to be due to Cyberdreams' closure.[36]

Sequels

[edit]The first sequel to Species, Species II was released theatrically on April 10, 1998.[37] The film depicts astronauts on a mission to Mars being attacked by the aliens from Species, and the events that ensue upon their return to Earth. There, Dr. Baker has been working on Eve, a more docile clone of Sil. Madsen and Helgenberger reprised their roles, while Henstridge played Eve. Species II received overwhelmingly negative reviews from critics, garnering a 9% approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes,[38] and Madsen denounced it as a terrible film.[39] The film's director, Peter Medak, attributed the failure of the film to not picking up the infected rat ending of the original film.[40] Navarro later authored the novelization for Species II which followed the film's original screenplay with added scenes.[41]

The second sequel, Species III, followed in 2004. It premiered on Sci-Fi Channel on November 27,[42] with a DVD release on December 7.[43] The film's plot starts where Species II ends, revolving around Sunny Mabrey's character Sara, the daughter of Eve, reared by a doctor played by Robert Knepper. Sara, an alien-human hybrid, seeks other hybrids to mate with. Henstridge appears in a cameo at the beginning of the film. Two out of six critics mentioned on Rotten Tomatoes gave it a positive rating,[44] with DVD Talk's reviewer noting that it is "a more cohesive and sensible flick than [Species II] is, but ultimately, it's just a lot of the same old schtick", while Film Freak Central called it "amateurish" and "vapid".[45] A fourth film, Species: The Awakening came out in 2007, following the schedule of Species III of Sci-Fi Channel premiere and subsequent DVD release.[46][47] None of the actors from the original film returned in this sequel, which instead starred Helena Mattsson as the alien-hybrid seductress.[48]

See also

[edit]- A for Andromeda (1961)

- Embryo (1976)

- Demon Seed (1977)

- Splice (2009)

- Under The Skin (2013)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Species (1995)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Species at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b c d "Species (1995) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Making of Species: The Origin", Species Definitive Edition DVD disk 2

- ^ a b c George, Susan A. (2001). "Not exactly 'of woman born': Procreation and creation in recent science fiction films". Journal of Popular Film & Television. 28 (4): 176–83. doi:10.1080/01956050109602839. S2CID 191567924.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin (March 15, 2011). Tracking the Chupacabra: the Vampire Beast in Fact, Fiction and Folklore. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 129–140. ISBN 978-0-8263-5015-2.

- ^ Fugarino, Virginia S. (September 28, 2011). "Books for review: Tracking the Chupacabra: The Vampire Beast in Fact, Fiction, and Folklore". Journal of Folklore Research. Indiana University. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Robley, Les Paul (March 1996). "H. R. Giger—Origin of "Species"" (PDF). Cinefantastique. 27 (7): 16–22. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Warren, Bill (September 1995). "In the blood". Starlog. No. 218. pp. 78–81. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Creating a New Species". Archived from the original on March 29, 1997. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Giger, H.R. (1996). Species Design. Morpheus International. ISBN 1-883398-12-6.

- ^ Cox, Dan (April 13, 1994). "Donaldson on MGM pic". Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ Scapperotti, Dan (June 1996). "Natasha Henstridge - Species' Sexy Seductress" (PDF). Femme Fatales. Vol. 4, no. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Robley, Les Paul (March 1996). "Building Giger's alien" (PDF). Cinefantastique. 27 (7): 23–28. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "An Unnatural Habitat". Archived from the original on March 29, 1997. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Natale, Richard. Time Right for 'Species' to Emerge, Los Angeles Times, July 10, 1995.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Tooze, Gary W. "Species Blu-ray - Natasha Henstridge". DVD Beaver. Archived from the original on October 20, 2004. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Species VHS. ASIN 6304509189.

- ^ Liebman, Martin (December 2, 2011). "Species Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Species Collector's Edition Blu-ray Detailed". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 30, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Species (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ "Species Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 7, 1995). "Species Movie Review & Film Summary (1995)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ James, Christine (July 7, 1995). "Species". Boxoffice. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Species". Reelviews. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 14, 1995). "Species". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 11, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Cheshire, Godfrey (June 30, 1995). "Species". Variety. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Weinberg, Scott (September 20, 2005). "Species Trilogy". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (December 8, 1995). "FILM REVIEW – 'Species' Suited for Extinction / Sexy sci-fi thriller is not quite camp". SFGate.com. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Rainer, Peter (July 7, 1995). "MOVIE REVIEW: 'Species' Provides a Few Screams and a Good Cast". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Navarro, Yvonne; Feldman, Dennis (June 1, 1995). Species: A Novel. Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-57404-3.

- ^ "1996 Audie Awards®". Audio Publishers Association. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Rennie, Gordon; Hester, Phil; Parks, Ande (August 5, 1997). Species: Human Race. Dark Horse. ISBN 978-1-56971-219-1.

- ^ Woodruff, Teeuwynn (1995). The World of Species. West End Games. ISBN 0-87431-364-3.

- ^ Gillen, Marilyn A. "The Origin of a Multimedia 'Species', Billboard (July 1, 1995)

- ^ "'City of Angels' Takes Wing in Heavenly Opening Weekend". Los Angeles Times. April 13, 1998. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Species II (1998)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Ingham, Tim (October 27, 2009). "Michael Madsen". Metro.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Medak, Peter (director); Feldman, Dennis; Brancato, Chris (writers) (1998). Species II (DVD). DVD commentary

- ^ Turner, Brad (director); Ripley, Ben (writer) (November 27, 2004). Species III (Television film). Sci-Fi Channel.

- ^ Turner, Brad (director); Ripley, Ben (writer) (December 7, 2004). Species III (DVD). MGM.

- ^ "Species III (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on June 2, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Chow, Walter (January 29, 2013). "Species III (2004) [Unrated Edition] + Resident Evil: Apocalypse (2004) [Special Edition] – DVDs". Film Freak Central. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ Lyon, Nick (director); Ripley, Ben (writer) (September 29, 2007). Species: The Awakening (Television film). Sci-Fi Channel.

- ^ Lyon, Nick (director); Ripley, Ben (writer) (October 2, 2007). Species: The Awakening (DVD). MGM Home Video.

- ^ Henderson, Stuart (October 1, 2007). "Species IV". PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

External links

[edit]

- 1995 films

- Species (film series)

- 1995 horror films

- 1990s chase films

- 1990s monster movies

- 1990s science fiction horror films

- American chase films

- American erotic horror films

- American science fiction horror films

- American science fiction thriller films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films directed by Roger Donaldson

- Films scored by Christopher Young

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films shot in Utah

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Puerto Rico

- Films adapted into comics

- Fictional extraterrestrial–human hybrids

- American pregnancy films

- 1990s pregnancy films

- 1990s American films

- Films produced by Frank Mancuso Jr.

- Science fiction about first contact

- 1995 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language action thriller films