Snake Island (Ukraine)

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2012) |

Native name: острів Зміїний | |

|---|---|

2008 photo of the island | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Black Sea |

| Coordinates | 45°15′N 30°12′E / 45.250°N 30.200°E |

| Area | 0.17 km2 (0.066 sq mi) |

| Length | 662 m (2172 ft) |

| Width | 440 m (1440 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 41 m (135 ft) |

| Highest point | N/An |

| Administration | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | Izmail Raion |

| Hromada | Vylkove |

| Largest settlement | Bile |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Pop. density | 600/km2 (1600/sq mi) |

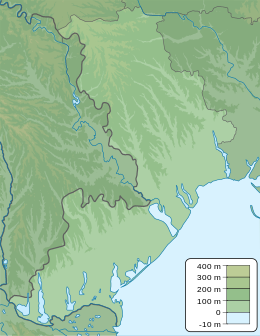

45°15′18″N 30°12′15″E / 45.25500°N 30.20417°E Snake Island, also known as Serpent Island, White Island, Island of Achilles or Zmiinyi Island (Ukrainian: острів Змії́ний, romanized: ostriv Zmiinyi; Romanian: Insula Șerpilor), is a Ukrainian island located in the Black Sea, near the Danube Delta, with an important role in delimiting Ukrainian territorial waters.

The island has been known since classical antiquity, and during that era hosted a Greek temple to Achilles.[1] Today, it is administered as part of Izmail Raion of Ukraine's Odesa Oblast.

The island is populated, reported to have under 30 people in 2012. A village, Bile, was founded in February 2007 with the purpose of consolidating the status of the island as an inhabited place. This happened during the period in which the island was part of a border dispute between Romania and Ukraine from 2004 to 2009, during which Romania contested the technical definition of the island and borders around it. The territorial limits of the continental shelf around Snake Island were delineated by the International Court of Justice in 2009,[2] providing Romania with almost 80% of the disputed maritime territory.[3]

In the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, two Russian navy warships attacked and captured Snake Island.[4] It was subsequently bombarded heavily by Ukraine[5] and recaptured within a few months, following a Russian withdrawal.[6]

Geography

[edit]

Snake Island is located 35 km from the coast, east of the mouth of the Danube River. The island is irregularly shaped, with an area of 0.205 km2 (0.079 sq mi) and a maximum diameter of about 700m. The gently sloping terrain reaches its highest point 41 metres (135 ft) above sea level.

The bedrock of the island consists of Silurian and Devonian sedimentary rocks, primarily metamorphosed, highly cemented quartzite conglomerate-breccias, with subordinate conglomerate, sandstone and clay, which form cliffs surrounding the island up to 25 metres high. The structural geology of the island is defined by a wavy monocline oriented to the northeast, with a small anticline in the eastern part of the island. The island is crisscrossed by faults with both N-S and NE-SW orientations.[7]

The nearest coastal location to the island is Kubanskyi Island on the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta, located 35 km (22 mi) away between the Bystroe Canal and Skhidnyi Channel. The closest Romanian coastal city, Sulina, is 45 km (28 mi) away. The closest Ukrainian city is Vylkove, 50 km (31 mi); however, there also is a port Ust-Dunaisk, 44 km (27 mi) away from the island.

For the end of 2011 in Zmiinyi Island coastal waters, 58 fish species (12 of which are included into the Red Book of Ukraine)[8] and six crab species were recorded. A presidential decree of 9 December 1998, Number 1341/98, declared the island and coastal waters as a state-protected area. The total protected area covers 232 hectares (570 acres).

The island was one of the last hauling-out sites in the basin for critically endangered Mediterranean monk seals until the 1950s.[9]

Population and infrastructure

[edit]

About 100 inhabitants live on the island's only settlement, Bile, mostly frontier guard servicemen with their families and technical personnel. In 2003, an initiative of the Odesa I. I. Mechnikov National University established the Ostriv Zmiinyi marine research station every year, at which scientists and students from the university conduct research on local fauna, flora, geology, meteorology, atmospheric chemistry, and hydrobiology.

In accordance with a 1997 Treaty between Romania and Ukraine, the Ukrainian authorities withdrew an army radio division, demolished a military radar, and transferred all other infrastructure to civilians. Eventually, the Romania-Ukraine international relationships soured (see "Maritime delimitation" section) when Romania tried to assert that the island is no more than a rock in the sea. In February 2007, the Verkhovna Rada approved establishing a rural settlement as part of Vylkove city which is located some distance away at the mouth of the Danube.

In addition to a helicopter platform, in 2002 a pier was built for ships with up to 8 meter draught, and construction of a harbour is[when?] underway. The island is supplied with navigation equipment, including a 150-year-old lighthouse. Electric power is provided by a dual solar/diesel power station. The island also has civil infrastructure such as the marine research station, a post office, a bank (branch of the Ukrainian bank "Aval"), the first-aid station, a satellite television provider, a phone network, a cell phone tower, and an Internet link. Most of building structures are located either in the middle of the island by a lighthouse or the northeastern peninsula of the island by its pier.

The island lacks a fresh water source.[10] Its border guard contingent is regularly resupplied by air.[11] Since 2009 the development of the island was suspended due to financing which caused a great degree of concern of local authorities asking for more funding from the state.[12]

Lighthouse

[edit]| Snake Island Lighthouse | |

|---|---|

Mаяк | |

The lighthouse in the background in 1896 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | service |

| Town or city | Bile |

| Country | Ukraine |

| Elevation | 40 metres (130 ft) |

| Completed | Autumn 1842 |

| Height | 12 metres (39 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | Black Sea Fleet |

The Snake Island Lighthouse was built in the autumn of 1842[13] by the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Empire. The lighthouse is an octagonal-shaped building, 12 meters tall, located near the highest elevated area of the island, 40 meters above the sea level. The lighthouse built on site of the previously destroyed temple of Achilles is adjacent to a housing building. The remnants of the Greek temple were found in 1823.

As lighthouse technology progressed, in 1860 new lighthouse lamps were bought from England, and one of them was installed in the Lighthouse in 1862. In the early 1890s a new kerosene lamp was installed, with lamp rotating equipment and flat lenses. It improved the lighthouse visibility to 37 kilometres (20 nmi). The lighthouse was either destroyed or damaged in the First World War (it is not clear which). It was subsequently rebuilt (see #World War I below).

The lighthouse was heavily damaged during World War II by Soviet aviation and German retreating forces. It was restored at the end of 1944 by the Odesa military radio detachment. In 1949 it was further reconstructed and equipped by the Black Sea Fleet. The lighthouse was further upgraded in 1975 and 1984. In 1988 a new radio beacon "KPM-300" was installed with radio signal range of 280 kilometres (150 nmi).

In August 2004, the lighthouse was equipped with a radio beacon "Yantar-2M-200", which provides differential correction signal for global navigation satellite systems GPS and GLONASS.

The lighthouse is listed as UKR 050 by ARLHS, EU-182 by IOTA, and BS-07 by UIA.

History and mythology

[edit]

Ancient history

[edit]The island was named by the Greeks Leuke (‹See Tfd›Greek: Λευκή, 'White Island') and was similarly known by Romans as Alba, probably because of the white marble formations that can be found on the isle. According to Dionysius Periegetes, it was called Leuke, because the serpents there were white.[14] According to Arrian, it was called Leuke due to its color.[15] He and Stephanus of Byzantium mentioned that the island was also referred to as the Island of Achilles (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ἀχιλλέως νῆσος[15] and Ἀχίλλεια νῆσος[16]) and the Racecourse of Achilles (Δρόμον Ἀχιλλέως[15] and Ἀχίλλειος δρόμος[16]), though this is now identified with the Tendra Spit.

The island was sacred to the hero Achilles and had a temple of the hero with a statue inside.[17] Solinus wrote that on the island there was a sacred shrine.[18] According to Arrian in the temple there were many offerings to Achilles and Patroclus.[15] Furthermore, people came to the island and sacrificed or set animals free in honour of Achilles.[19] He also added that people said that Achilles and Patroclus appeared in front of them as hallucinations or in their dreams while they were approaching the coast of the island or sailing a short distance from it.[20] Pliny the Elder wrote that the tomb of the hero was on the island.[21] According to the legend, on the island no bird flew higher than the temple of Achilles.[22]

The uninhabited isle Achilleis ("of Achilles") was the major sanctuary of the hero, where "seabirds dipped their wings in water to sweep the temples clean", according to Constantine D. Kyriazis. Several temples of Thracian Apollo can be found here, and there are submerged ruins.

According to Greek myths the island was created by Poseidon for Achilles to inhabit, but also for sailors to have an island to anchor at the Euxine Sea,[23] but the sailors should never sleep on the island.[24] According to a surviving epitome of the lost Trojan War epic of Arctinus of Miletus, the remains of Achilles and Patroclus were brought to this island by Thetis, to be put in a sanctuary, furnishing the aition, or founding myth of the Hellenic cult of Achilles centred here. According to another myth Thetis gave the island to Achilles and let him live there.[15] The oracle of Delphi sent Leonymus (other writers called him Autoleon[25]) to the Island, telling him that there Ajax the Great would appear to him and cure his wound.[26] Leonymus said that on the island he saw Achilles, Ajax the Great, Ajax the Lesser, Patroclus, Antilochus and Helen of Troy. In addition, Helen told him to go to Stesichorus at Himera and tell him that the loss of his sight was caused by her wrath.[27] Pomponius Mela wrote that Achilles was buried there.[28]

In Andromache, work of Euripides, Thetis mention the island and said that Achilles was "dwelling on his island home".[29]

Ruins believed to be of a square temple dedicated to Achilles, 30 meters to a side, were discovered by the Russian naval Captain N. D. Kritzkii in 1823, but the subsequent construction of a lighthouse on the very site obliterated all trace of it.[30] Ovid, who was banished to Tomis, mentions the island, so do Ptolemy and Strabo.[31] The island is described in Pliny the Elder's Natural History, IV.27.1. It is also described in Arrian's Letter to Emperor Hadrian, a historical document movingly drawn upon by Marguerite Yourcenar in her Memoirs of Hadrian.

Several ancient inscriptions were found on the island, including a 4th-century BC Olbiopolitan decree which praises someone for defeating and driving out the pirates that lived on the "holy island". Another inscription which found on the island and dates back to the fifth century BC writes: "Glaukos, son of Posideios, dedicated me to Achilles, lord of Leuke"[22]

A fragment was found on the island which was signed by the famous ancient painter Epiktetos and the potter Nikosthenes.[32]

The island was one of the three sites in the Black Sea which stand out in the cult of Achilles, the other two were the Racecourse of Achilles and the Pontic Olbia.[22]

Ottoman era

[edit]

The Greeks during the Ottoman Empire renamed it Fidonisi (Greek: Φιδονήσι, 'Snake Island') and the island gave its name to the naval Battle of Fidonisi, fought between the Ottoman and Russian fleets in 1788, during the course of the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792.

In 1829, following the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, the island became part of the Russian Empire until 1856.

In 1877, following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman Empire gave the island and Northern Dobruja region to Romania, as a reimbursement for the Russian annexation of Romania's Southern Bessarabia region.

World War I and interwar period

[edit]As part of the Romanian alliance with Russia, the Russians operated a wireless station on the island, which was destroyed on 25 June 1917 when it was bombarded by the Ottoman cruiser Midilli (built as SMS Breslau of the German Navy). The lighthouse (built by Marius Michel Pasha in 1860) was also damaged and possibly destroyed.[33]

The 1920 Treaty of Versailles reconfirmed the island as part of Romania. The lighthouse was rebuilt in 1922.[citation needed]

World War II

[edit]The island, under Romanian control during the Second World War, was the location of a radio station used by the Axis forces, which turned it into a target for the Soviet Black Sea Fleet.[34] The island's defences mainly consisted of several 122 mm and 76 mm anti-aircraft guns, captured from the Russians.[35] The Romanian marine platoon defending the island was also equipped with two 45 mm coastal guns, two 37 mm anti-aircraft guns, and two anti-aircraft machine guns.[36]

The first naval action took place on 23 June 1941, when the Soviet destroyer leader Kharkov together with the destroyers Bezposhchadny and Smyshlyonyi and several torpedo boats ran a patrol near the island, but found no Axis ships.[37]

On 9 July 1941, the Soviet destroyer leader Tashkent together with four other destroyers (Bodry, Boiky, Bezuprechny, and Bezposhchadny) conducted a shipping sweep operation near the island, but did not make any contacts.[38]

On 7 September 1941, two Soviet submarines of the Shchuka class (Shch-208 and Shch-213) and three of the M class (M-35, M-56, and M-62) conducted a patrol near the island.[39]

On 29–30 October and 5 November 1942, the Romanian minelayers Amiral Murgescu and Dacia, together with the Romanian destroyers Regina Maria, Regele Ferdinand, the Romanian flotilla leader Mărăști, the Romanian gunboat Stihi and four German R boats laid two mine barrages around the island.[40]

On 1 December 1942, while the Soviet cruiser Voroshilov together with the destroyer Soobrazitelny were bombarding the island with forty-six 180 mm and fifty-seven 100 mm shells, the cruiser was damaged by Romanian mines, but it managed to return to Poti for repairs under her own power. During the brief bombardment, she struck the radio station, barracks and lighthouse on the island, but failed to inflict significant losses.[41][42][43][44][45]

On 11 December 1942, the Soviet submarine Shch-212 was sunk by a Romanian minefield near the island along with all of her crew of 44.[46][47][48] The Soviet submarine M-31 was either sunk as well by the Romanian mine barrages near the island on 17 December,[49] or sunk with depth charges by the Romanian flotilla leader Mărășești on 7 July 1943.[50]

On 25 August 1943, two Romanian motorboats spotted a Soviet submarine near the island and attacked her with depth charges, but it managed to escape.[51]

The Romanian marines were evacuated from the island and Soviet troops occupied it on 29–30 August 1944.[52][53]

Post-WWII history

[edit]The Paris Peace Treaties of 1947 between the protagonists of World War II stipulated that Romania cede Northern Bukovina, the Hertsa region, Budjak, and Bessarabia to the Soviet Union, but made no mention of the mouths of the Danube and Snake Island.

Until 1948, Snake Island was a part of Romania. On 4 February 1948, during the delimitation of the frontier, Romania and the Soviet Union signed a protocol that left Snake Island and several islets on the Danube south of the 1917 Romanian-Russian border under Soviet administration. Romania disputed the validity of this protocol, since it was never ratified by either of the two countries; nevertheless it did not make any official claim on the territories.

The same year, in 1948, during the Cold War, a Soviet radar post was built on the isle (for both naval and anti-aircraft purposes).

The Soviet Union's possession of Snake Island was confirmed in the Treaty between the Government of the People's Republic of Romania and the Government of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics on the Romanian-Soviet State Border Regime, Collaboration and Mutual Assistance on Border Matters, signed in Bucharest on 27 February 1961.

Between 1967 and 1987, the USSR and Romanian side negotiated the delimitation of the continental shelf. The Romanian side refused to accept a Russian offer of 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi) out of 6,000 km2 (2,300 sq mi) around the island in 1987.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine inherited control over the island. A number of Romanian parties and organizations consistently claimed it should be included in its territory. According to the Romanian side, in the peace treaties of 1918 and 1920 (after World War I), the isle was considered part of Romania, and it was not mentioned in the 1947 border-changing treaty between Romania and the Soviet Union.

In 1997, Romania and Ukraine signed a treaty in which both states "reaffirm that the existing border between them is inviolable and therefore, they shall refrain, now and in future, from any attempt against the border, as well as from any demand, or act of, seizure and usurpation of part or all the territory of the Contracting Party". However, both sides have agreed that if no resolution on maritime borders can be reached within two years, then either side can go to the International Court of Justice to seek a final ruling.

In 2007, the island's only settlement Bile was founded.

In 2008, twelve Ukrainian border guards died when their helicopter flying from Odesa to Snake Island crashed, killing all but one on board.[11]

Until 18 July 2020, the island belonged to Kiliia Raion. The raion was abolished in July 2020 as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Odesa Oblast to seven. The area of Kiliia Raion was merged into Izmail Raion.[54][55]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]Militarily, Snake Island, 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the coast of Ukraine, is within the range of missile, artillery, and drone strikes from the shore, and exposed to attacks from all directions from air and sea, making any garrison "sitting ducks".[56] It is a strategically significant island in the Black Sea, and Russian control over the island would allow a total blockade of the Ukrainian port city of Odesa.[56]

On 24 February 2022, on the first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, two Russian naval warships Vasily Bykov and Moskva, attacked Snake Island.[59] Upon receiving a transmission from one of the Russian naval warships requesting surrender or else threatening bombardment, a Ukrainian border guard responded, "Russian warship, go fuck yourself."[60] The response gained worldwide attention and became a symbol of Ukrainian resistance.[61][62] Later on the same day, Russian forces landed and captured the island.[63]

Initially, the Ukrainian government erroneously reported that all 13 members of the garrison had died in the attack, and President Volodymyr Zelensky "posthumously" awarded the Hero of Ukraine, Ukraine's highest award, to the 13 defenders.[61][62][64] The Ukrainian navy clarified later in February that the garrison were alive.[65] On 29 March 2022, the Defence Ministry of Ukraine posted on Twitter that the author of the famous phrase had been freed from captivity and given a medal for bravery.[66][67] The Ukrainian Postal Service in April 2022 issued a stamp showing a Ukrainian soldier showing the finger (an offensive gesture of defiance) to the Russian ship Moskva.[68]

Ukrainian forces launched an operation to expel the Russians from Snake Island, targeting exposed Russian positions in an over four month-long campaign.[56][69] Ukrainian military sources said they carried out attacks on both the island proper and on any Russian vessels bringing troops and weapons to it.[56] New Western weapons supplies to Ukraine were key to turning the tide of the campaign in Ukraine's favor, especially the HIMARS rocket system.[70]

In late June 2022, Russian forces withdrew from the island[69] in what the BBC referred to as both symbolic and strategic victory for Ukraine.[56][71] Ukrainian sources claimed the Russians fled in two speedboats after being unable to withstand Ukrainian strikes.[72] Russia referred to the withdrawal as a "gesture of goodwill" after completing its military objectives on the island.[73]

On 8 July 2023 president Zelensky visited the island to commemorate Ukrainian soldiers who defended it.[74] On 13 July 2023 Russian forces dropped a single aerial bomb on the island.[75]

Maritime delimitation

[edit]

The status of Snake Island was important for delimitation of continental shelf and exclusive economic zones between Romania and Ukraine. If Snake Island were recognized as an island, then continental shelf around it should be considered as Ukrainian water. If Snake Island were not an island, but an islet,[10] then in accordance with international law the maritime boundary between Romania and Ukraine should be drawn without taking into consideration the isle location.

On 4 July 2003, the President of Romania Ion Iliescu and the President of Russia Vladimir Putin signed a treaty about friendship and cooperation. Romania promised not to contest territories of Ukraine or Moldova, which it lost to the Soviet Union after World War II, but requested that Russia as a successor of the Soviet Union recognized in some form its responsibility for what had happened.[76]

On 16 September 2004, the Romanian side brought a case against Ukraine to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in a dispute concerning the maritime boundary between the two States in the Black Sea.[77]

In 2007, Ukraine founded the small settlement of Bile on the island, which was criticized by Romania.[78]

On 3 February 2009, the ICJ delivered its judgment, which divided the sea area of the Black Sea along a line which was between the claims of each country. The Court invoked the disproportionality test in adjudicating the dispute, noting that the ICJ, "as its jurisprudence has indicated, it may on occasion decide not to take account of very small islands or decide not to give them their full potential entitlement to maritime zones, should such an approach have a disproportionate effect on the delimitation line under consideration" and owing to a previous agreement between Ukraine and Romania, the island "should have no effect on the delimitation in this case, other than that stemming from the role of the 12-nautical-mile arc of its territorial sea" previously agreed between the parties.[79]

See also

[edit]- Bystroye Canal

- Filfla

- Maican Island

- Romania–Ukraine relations

- Soviet Navy surface raids on Western Black Sea

- Russian warship, go fuck yourself

References and footnotes

[edit]Inline

[edit]- ^ Rusyaeva, Anna (1 January 2003). "The Temple of Achilles on the Island of Leuke in the Black Sea". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 9 (1–2): 1–16. doi:10.1163/157005703322114810. ISSN 0929-077X.

- ^ "International Court of Justice: Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine)". Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Insula Șerpilor: Decizie favorabilă României | DW | 03.02.2009". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Lamothe, Dan (26 February 2022). "Ukrainian border guards may have survived reported last stand on Snake Island". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Snake Island and battle for control in Black Sea". BBC News. 11 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Koshiw, Isobel (30 June 2022). "Ukraine says it has pushed Russian forces from Snake Island". The Guardian.

- ^ Cherkez, E.A.; Pogrebnaya, O.А.; Svitlychnyi, S.V.; Kozlova, T.V.; Medinets, S.V.; Buyanovskiy, A.O.; Medinets, T.S. (2020). "Using of radiometric method in studying of the Zmiinyi Island structural and tectonic features". XIV International Scientific Conference "Monitoring of Geological Processes and Ecological Condition of the Environment". Vol. 2020. Kyiv, Ukraine: European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers. pp. 1–5. doi:10.3997/2214-4609.202056065. S2CID 235055591.

- ^ Snigirov S, Goncharov O, Sylantyev S. The fish community in Zmiinyi Island waters: structure and determinants. Marine Biodiversity 2012. doi:10.1007/s12526-012-0109-4

- ^ Sergei R. Grinevetsky, Igor S. Zonn, Sergei S. Zhiltsov, Aleksey N. Kosarev, Andrey G. Kostianoy, 2014, The Black Sea Encyclopedia

- ^ a b Ruxandra Ivan (2012). New Regionalism Or No Regionalism?: Emerging Regionalism in the Black Sea Area. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4094-2213-6.

- ^ a b Ukrainian helicopter crash kills 12, Reuters, 27 March 2008

- ^ "An appeal of the Odesa Regional Council to the Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on the further development of infrastructure of the Snake Island and the Bile settlement of the Kiliia Raion of Odesa Oblast" (PDF). Ukraine Odesa Regional Council Decisions.

- ^ Vitrenko's Odesa website (in Russian)

- ^ Dionysius of Alexandria, Guide to the Inhabited World, §540

- ^ a b c d e Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Sea, §32

- ^ a b Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §A152.9

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, § 3.19.11

- ^ Solinus, Polyhistor, §19.1

- ^ Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Sea, §33

- ^ Arrian, Periplus of the Euxine Sea, §34

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, §4.26.1

- ^ a b c Marta González González (January 2018). Achilles. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67701-2.

- ^ Philostratus, Heroica, §746

- ^ Philostratus, Heroica, §747

- ^ Conon, Narrations (Photius), 18

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, §3.19.12

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, §3.19.13

- ^ Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, §2.98

- ^ Euripides, Andromache, 1231

- ^ Anna S. Rusyaeva, "The temple of Achilles on the island of Leuke in the Black Sea".

- ^ Geography, book II.5.22

- ^ L. D. Caskey, J. D. Beazley, Attic Vase Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 118. 00.334 KANTHAROS from TARQUINIA PLATE LXVIII

- ^ "firstworldwar.com". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ Robert Gardiner, Warship 1991, p. 142

- ^ Rotaru, Jipa; Damaschin, Ioan (2000). Glorie și dramă: Marina Regală Română, 1940-1945 (in Romanian). Ion Cristoiu Publishing. p. 105.

- ^ Moșneagu, Marian. Politica navală postbelică a României (1944-1958) (in Romanian). p. 402.

- ^ Donald A Bertke, World War II Sea War, Vol 4: Germany Sends Russia to the Allies, p. 73

- ^ Donald A Bertke, World War II Sea War, Vol 4: Germany Sends Russia to the Allies, p. 134

- ^ Donald A Bertke, World War II Sea War, Vol 4: Germany Sends Russia to the Allies, p. 260

- ^ Nicolae Koslinski, Raymond Stănescu, Marina română in al doilea război mondial: 1942–1944, pp. 53-54 (in Romanian)

- ^ Rotaru, Jipa; Damaschin, Ioan (2000). Glorie și dramă: Marina Regală Română, 1940-1945 [Glory and drama: Romanian Royal Navy, 1940-1945] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Ion Cristoiu Publishing. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-9-73995-447-1.

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C (2015). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-59884-947-9.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C (2012). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 114.

- ^ Koslinski, Nicolae; Stănescu, Raymond (1997). Marina Română in al Doilea Război Mondial Vol 2: 1942-1944 [Romanian Navy in the Second World War Volume 2: 1942-1944] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Făt-Frumos. p. 56. OCLC 493419659.

- ^ Yakubov, Vladimir; Worth, Richard. "The Soviet Light Cruisers of the Kirov Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2009. p. 92.

- ^ Donald A Bertke, Gordon Smith, Don Kindell,World War II Sea War, Vol 8: Guadalcanal Secured, p. 77

- ^ Shch-212 on uboat.net

- ^ Shch-212 on wrecksite.eu

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "M-31". uboat.net. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Whitley, Michael J. (1999). Destroyers of World War Two: an international encyclopedia. London: Arms & Armour. p. 224. ISBN 1-85409-521-8. OCLC 46505277.

- ^ Rotaru, Jipa; Damaschin, Ioan (2000). Glorie și dramă: Marina Regală Română, 1940-1945 (in Romanian). Ion Cristoiu Publishing. p. 127.

- ^ Nicolae Koslinski, Raymond Stănescu, Marina română in al doilea război mondial: 1944-1945, p. 141 (in Romanian)

- ^ Victor Roncea, Axa: noua Românie la Marea Neagră, p. 209 (in Romanian)

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

- ^ a b c d e Lukov, Yaroslav; Kirby, Paul (30 June 2022). "Snake Island: Why Russia couldn't hold on to strategic Black Sea outcrop". BBC News.

- ^ "Ukrainian soldiers who told Russian warship 'go f*** yourself' honoured on postal stamps". itv.com. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Michael, Chris (12 March 2022). "Ukraine reveals 'Russian warship, go fuck yourself!' postage stamp". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Battle for Zmiinyi (Snake) Island. Reconstructing the heroic tale of Ukraine losing and reclaiming the critical island". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "A Russian warship tells Ukrainian soldiers to surrender. They profanely refuse". NPR. 25 March 2022. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Snake Island: Ukraine says soldiers killed after refusing to surrender". BBC. 26 February 2022.

- ^ a b Qin, Amy (25 February 2022). "Ukrainian troops killed on Snake Island to be honored". The New York Times. No. 25 Feb 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Ostrib Zmiinyy zakhopyly rosiis'ki okupanty - DPSU" Острів Зміїний захопили російські окупанти - ДПСУ [Snake Island was captured by the Russian occupiers - SBGS] (in Ukrainian). Gazeta UA. 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Haynes, Danielle (25 February 2022). "Slain Ukrainian guards deemed heroes for defiant stand on Snake Island". UPI. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian Navy confirms Snake Island soldiers are alive, POWs". jpost.com. The Jerusalem Post. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian soldier who told Russian warship to 'go f*** yourself' from Snake Island gets bravery award". Sky News. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Defense of Ukraine. "Roman Hrybov, the author of..." Twitter. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (20 April 2022). "Ukrainians wait in line for hours to buy commemorative Snake Island postage stamps". NPR. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b Will Ripley; Tim Lister; Victoria Butenko; Kostantyn Hak (20 December 2022). "On Snake Island, the rocky Black Sea outcrop that became a Ukraine war legend". Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Hunder, Max; Balmforth, Tom (30 June 2022). "Russia abandons Black Sea outpost of Snake Island in victory for Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Battle for Zmiinyi (Snake) Island. Reconstructing the heroic tale of Ukraine losing and reclaiming the critical island". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Russian forces leave Snake Island, keep up eastern assault". 30 June 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ "Минобороны объявило о выводе войск с острова Змеиный". РБК (in Russian). Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Zelenskyy visits Zmiinyi (Snake) Island on 500th day of full-scale war". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Russians drop high-explosive bomb on Zmiinyi Island at dawn". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Russia and Romania: compromise on history. BBC Russia. 4 July 2003

- ^ "Romania brings a case against Ukraine to the Court in a dispute concerning the maritime boundary between the two States in the Black Sea" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 16 September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2008.

- ^ "România a demonstrat și cu imagini din satelit că Insula Șerpilor nu face parte din coasta Ucrainei". România liberă (in Romanian). 3 September 2008.

- ^ "The Court establishes the single maritime boundary delimiting the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones of Romania and Ukraine" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009.

General

[edit]- Korrespondent.net: December 2003 report on Snake Island dispute, including aerial picture of the isle (in Russian)

- Korrespondent.net: Maritime Delimitation as of August 2005 (in Russian)

- BBC Romanian report on the bank opening (in Romanian)

- Aurelian Teodorescu, "Snake Island: Between rule of law and rule of force": The Ostriv Zmiinyi dispute from the Romanian perspective (in Romanian)

- Constantine D. Kyriazis, Eternal Greece: Achilles' sanctuary

- Nicolae Densușianu, Dacia Preistorică, 1913, I.4; Literary references to the island in Antiquity

- Cotidianul: "OMV cauta petrol linga Insula Serpilor" (in Romanian)

- Olexandr Fomin, The history of Snake Island Lighthouse, Zerkalo Nedeli, 26 February 2000. (in Russian)

- Civic Media, Ukraine and Romania in strategic war in the Black Sea, Civic Media, October 2007. (in Romanian)

- Civic Media, The natural right of Romania over the Serpent Island, Civic Media, October 2007. (in Romanian)

Further reading

[edit]- Michael Shafir (24 August 2004) Analysis: Serpents Island, Bystraya Canal, And Ukrainian-Romanian Relations, RFE/RL

- World Court Decides Ukraine-Romania Sea Border Dispute, RFE/RL News, 3 February 2009

- Clive Schofield (2012). "Islands or Rocks, Is that the Real Question? The Treatment of Island in the Delimitation of Maritime Boundaries". In Myron H. Nordquist; John Norton Moore; Alfred H.A. Soons; Hak-So Kim (eds.). The Law of the Sea Convention: US Accession and Globalization. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 322–340. ISBN 978-90-04-20136-1.

- Snake Island (Ukraine)

- Islands of the Black Sea

- Islands of Ukraine

- Foreign relations of Romania

- Foreign relations of Ukraine

- Romania–Soviet Union relations

- Romania–Ukraine relations

- Geography of Izmail Raion

- Landforms of Odesa Oblast

- Romania–Ukraine border

- Odesa University

- Naval battles of World War II involving the Soviet Union

- Naval battles of World War II involving Romania

- Naval battles of World War II involving Germany

- Military history of the Black Sea

- Achilles

- Vylkove urban hromada