Smoke signal

The smoke signal is one of the oldest forms of long-distance communication. It is a form of visual communication used over a long distance. In general smoke signals are used to transmit news, signal danger, or to gather people to a common area.

History and usage

[edit]In ancient China, soldiers along the Great Wall sent smoke signals on its beacon towers to warn one another of enemy invasion.[1][2] The colour of the smoke communicated the size of the invading party.[1] By placing the beacon towers at regular intervals, and situating a soldier in each tower, messages could be transmitted over the entire 7,300 kilometres of the Wall.[1] Smoke signals also warned the inner castles of the invasion, allowing them to coordinate a defense and garrison supporting troops.[2]

During the Kandyan period, soldiers stationed on the mountain peaks alerted each other of impending enemy attack (from English, Dutch or Portuguese people) by signaling from peak to peak. In this way, they could transmit a message to the King in just a few hours.[3][failed verification]

Misuse of the smoke signal is traditionally considered to have contributed to the fall of the Western Zhou dynasty in the 8th century BCE. King You of Zhou was said to have had a habit of fooling his warlords with false warning beacons to amuse Bao Si, his concubine.[4]

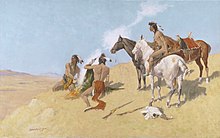

North American indigenous peoples also communicated via smoke signal. Each tribe had its own signaling system and understanding. A signaler started a fire on an elevation typically using damp grass, which caused a column of smoke to rise. The grass was taken off as it dried and another bundle was placed on the fire. Reputedly the location of the smoke along the incline conveyed a meaning. If it came from halfway up the hill, it signaled that all was well; but from the top of the hill, it signified danger.[5]

Smoke signals remain in use today. The College of Cardinals uses smoke signals to indicate the selection of a new Pope during a papal conclave. Eligible cardinals conduct a secret ballot until someone receives a vote of two-thirds plus one. The ballots are burned after each vote. Black smoke indicates a failed ballot, and white smoke means a new Pope has been elected.

Colored smoke grenades are commonly used by military forces to mark positions, especially during calls for artillery or air support.

Smoke signals may also refer to smoke-producing devices used to send distress signals.[6][7]

Examples

[edit]Native Americans

[edit]Lewis and Clark's journals cite several occasions when they adopted the Native American method of setting the plains on fire to communicate the presence of their party or their desire to meet with local tribes.[8]

Yámana

[edit]Yámanas of South America used fire to send messages by smoke signals, for instance if a whale drifted ashore.[9] The large amount of meat required notification of many people so that it would not be wasted.[10] They might also have used smoke signals on other occasions—thus it is possible that Magellan saw such fires and was inspired to name the landscape Tierra del Fuego ("Land of Fire"); however, he may have seen the smoke or lights of natural phenomena.[11][12]

Noon Gun

[edit]The Cape Town Noon Gun, specifically the smoke its firing generates, was used to set marine chronometers in Table Bay.

Aboriginal Australians

[edit]Aboriginal Australians throughout Australia have used smoke signals for various purposes—[13][14][15][16] sometimes to notify others of their presence, particularly when entering lands which were not their own.[13] Sometimes used to describe visiting whites, smoke signals were the fastest way to send messages.[16] Smoke signals were sometimes to notify of incursions by hostile tribes, or to arrange meetings between hunting parties of the same tribe. This signal could be from a fixed lookout on a ridge or from a mobile band of tribesman.[15] "Putting up a smoke" often promoted nearby individuals or groups to reply with their own signals.[14][15] Different colours of smoke (black, white or blue, depending on whether the material being burnt was wet grass, dry grass, reeds or other materials) were used to convert information, as was the smoke's shape (a column, ball or ring), allowing a messaging system sophisticated enough to include the names of individual tribesmen.[15] Like other means of communication, signals could be misinterpreted. In one recorded instance, a smoke signal reply translated as "we are coming" was misinterpreted as joining a war party for protection of the tribe, when it was actually to indicate hunting parties coming together after a successful hunt.[15]

Aviation

[edit]Modern aviation has made skywriting possible.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Ivan, Djordjevic (2010). Coding for Optical Channels. Springer US. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4419-5569-2. OCLC 699999686.

- ^ a b Du, Yumin; Chen, Wenwu; Cui, Kai; Guo, Zhiqian; Wu, Guopeng; Ren, Xiaofeng (2021-02-16). "An exploration of the military defense system of the Ming Great Wall in Qinghai Province from the perspective of castle-based military settlements". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 13 (3): 46. Bibcode:2021ArAnS..13...46D. doi:10.1007/s12520-021-01283-7. ISSN 1866-9557. S2CID 231940516.

- ^ Knox, Robert (2004). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon in the East Indies Together with an Account of the Detaining in Captivity the Author and Divers other Englishmen Now Living There, and of the Author's Miraculous Escape. Project Gutenberg. OCLC 703947445 at Project Gutenberg

- ^ Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian. Vol. 4.

- ^ "Smoke Signal". addpmp.slamjam.com. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Pyrotechnic device, Feb 4, 1964, retrieved 2017-02-01

- ^ Smoke signal, Nov 28, 1967, retrieved 2017-02-01

- ^ "Lewis and Clark Journals, July 20, 1805".

- ^ Gusinde 1966:137–139, 186

- ^ Itsz 1979:109

- ^ "The Patagonian Canoe". Pages.interlog.com. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ Extracts from the following book. E. Lucas Bridges: Uttermost Part of the Earth. Indians of Tierra del Fuego. 1949, reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc (New York, 1988).

- ^ a b Myers, 1986: 100

- ^ a b "Report on Patrol to Lake Mackay Area June/July 1957". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e Idriess, Ion L (1953). The Red Chief. ettimprint.

- ^ a b Idriess, Ion L (1937). Over the Range. ettimprint.

References

[edit]- Gusinde, Martin (1966). Nordwind—Südwind. Mythen und Märchen der Feuerlandindianer (in German). Kassel: E. Röth.

- Itsz, Rudolf (1979). "A kihunyt tüzek földje". Napköve. Néprajzi elbeszélések (in Hungarian). Budapest: Móra Könyvkiadó. pp. 93–112. Translation of the original: Итс, Р.Ф. (1974). Камень солнца (in Russian). Ленинград: Detskaya Literatura. Title means: “Stone of sun”; chapter means: “The land of burnt-out fires”. (Leningrad: "Children's Literature" Publishing.)

- Myers, Fred (1986). Pintupi Country, Pintupi Self. USA: Smithsonian Institution.